The Amateur-Professional Debate: an Exploration of Attitudes And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kenmare News [email protected] Page 23

FREE November 2012K ENMARE 087 2513126 • 087 2330398 N VolEWS 9, Issue 10 Your Town, Kenmare Your Community, Chronicle Your History. coming soon! SeanadóirSenator Marcus Mark O’Dalaigh Daly SherryAUCTIONEERS FitzGerald & VALUERS T: 064-6641213 Daly Beann na Kenmare Mara, Hospital is Dawros, heading towards Kenmare Mob: 086 803 2612 second fix Panoramic sea view of Kenmare Bay & Dinish Island Built in 1970’s – 3 bed - 900 sq ft Clinics held in the Set on c.0.6 acres Atlantic Bar and all 100 metres Star Marina, 4.3 miles to Kenmare Michael Asking Price: €135,000 surrounding Healy-Rae parishes on a T.D. Sean Daly & Co Ltd regular basis. Insurance Brokers EVERY SUNDAY NIGHT IN KILGARVAN: Before you Renew your Insurance (Household, Motor or Commercial) HEALY-RAE’S MACE - 9PM – 10PM Talk to us FIRST - 064-6641213 HEALY-RAE’S BAR - 10PM – 11PM We Give Excellent Quotations. Tel: 064 66 32467 • Fax : 064 6685904 • Mobile: 087 2461678 Sean Daly & Co Ltd, 34 Henry St, Kenmare T: 064-6641213 E-mail: [email protected] • Johnny Healy-Rae MCC 087 2354793 TAXI KENMARE Cllr. Patrick Denis & Mags Griffin Connor-Scarteen M: 087 2904325 087 614 7222 Rural Jobs StrategySee Page 16 Kenmare Furniture Bedding & Suites 064 6641404 OPENINGKenmare Business HOURS: Park, Killarney MON.-SAT.: Road, Kenmare. 10am-6pm Email: [email protected] Web: www.kenmarefurniture.com Come in and see the fabulous new ranges now in stock Page 2 Phone 087 2513126 • 087 2330398 Kenmare News Tuosist Social History Project is on the home stretch now! We are The December edition of The Kenmare News in the process of editing the many articles we’ve received, and will be published on Monday December 17th and closing sorting through the hundreds of photos to illustrate the many and date for submissions is Monday December 10th. -

Tigers Big Man to Retire

EDITION 18 $2.50 TIGERS BIG MAN TO RETIRE 22008008 HHOMEOME & AAWAYWAY SSEASONEASON IINN RREVIEWEVIEW CCHRISHRIS RROUKEOUKE PPUTSUTS PPENEN TTOO PPAPERAPER quality ro camp und E A GOLD inside NAT CO The GM’s Report 4 O IN AFL Canberra Limited D Big DJ to retire 6 Bradman Stand Manuka Oval HE GA Manuka Circle ACT 2603 T TE PO Box 3759, Manuka ACT 2603 AT Ph 02 6228 0337 2008 Home & Away Season in Review 8 Fax 02 6232 7312 Chris Rouke puts pen to paper 12 Publisher Coordinate PO Box 1975 Seniors 14-21 WODEN ACT 2606 Ph 02 6162 3600 Email [email protected] Reserves 22 Neither the editor, the publisher nor AFL Canberra accepts liability of any form for loss or harm of any type however caused All design material in the magazine is copyright protected and Under 18’s 23 cannot be reproduced without the written permission of Coordinate. Editor Jamie Wilson Ph 02 6162 3600 Round 18 Email [email protected] Designer Logan Knight Ph 02 6162 3600 Email [email protected] vs Photography Andrew Trost Email [email protected] Manuka Oval, Sun 17th August, 2pm Manuka Oval, Sat 16th August, 2pm vs Dairy Farmers Park, Sat 16th August, 2pm vs Manuka Oval, Sun 17th August, 2pm In the box with the GM david wark This weekend we see the final games for both It is not for me to be speculating on the future Tuggeranong and Queanbeyan. Their stories are of players but I understand it to be common extraordinarily different. -

Reifreann an Daingin Gan Bhrí for the Irish Language and Irish Seolfar Lámhleabhar Traenála Ar an Medium Education

acmhainn eagna www.acmhainn.ie BOCHTANAS: “Ach bhí a fhios agam le fada 43 riamh - nó tá mo cheann sean - gur fíordheacair a bheith ionraic má tá tú róbhocht, agus gur mar an gcéanna ag an uchtach é. Is fearrde na suáilcí dúshraith de mhaoin an tsaoil a bheith fúthu.” – Seosamh Mac Grianna, Mo Bhealach Féin www.nuacht.com NUACHTÁN LAETHÚIL NA GAEILGE Cuardaigh nuathéarmaíocht na Gaeilge ar www.acmhainn.ie 9 771364 749027 Praghas molta miondíola LÁ: Iml 27 Uimh 207 Dé Máirt 24 Deireadh Fómhair 2006(Poblacht na hÉireann) 80c 80c / 50p LáGonta Beidh seimineár ar inimirce, imeascadh agus an Ghaeilge á reáchtáil ag an ghrúpa iMeasc ar 27 Deireadh Fómhair. A seminar on immigration, integration and Irish will take place in Dublin on 27 October. ➔ 3 ––––––––––––––––––––––––– Díríonn Méadhbh Ní hEadhra ar an gcontúirt go bhfuil íomhánna leictreonacha de pháistí á uaschóipeáil ar an idirlíon. Méadhbh Ní hEadhra isn’t convinced of the benefits of the internet - especially as pictures of children are being uploaded on dubious sites ➔ without their permission. 4 Mháirseáil lucht agóide Ros Muc ar son phobal Ros Dumhach Dé Domhnaigh agus iad ag léiriú tacaíochta ––––––––––––––––––––––––– Rosc Catha Ros Muc: dá gcairde i nGaeitacht Mhaigh Eo. Scéal iomlán agus tuilleadh pictiúr ar Lch 3 Díbhinn síochána do naíscoil Le Concubhar Ó Liatháin na ar an suíomh agus cúiteamh a fháil ar ndéanfadh siad infheistiú i naíscoil a Tá tuismitheoirí agus daltaí i an díshealbhú gan choinne a rinneadh. thógáil sa cheantar. Dónall Ó Conaill, gceantar na Carraige Báine -

Hurling--Ireland’S Ancient National Game the Test of Time

Inside: Allianz Cumann na mBunscol News l Photos/Stories Galore 50th Issue Spring 2013 Volume 17, Number 2 €3.00 www.thegreenandwhite.com Scaling the Heights Limerick senior footballers reach the very top as G&W reaches Limerick Stars in Action P. 9 50th issue! Interviews: John Allen Maurice Horan, & Johnny Doyle BEST COUNTY PUBLICATION The Green & White in 7-TIME Rome…and Antarctica!” NATIONAL AWARD WINNER PLUS Puzzles, Competitions and more... The Green & White Spring 2013 Spring 2013 Issue Number 50 Spring 2013 Volume 17 Number 2 Follow us on Twitter @LimerickGAAZine The Throw In If you just got your copy of The Green and White at school, then This issue you’re much too young to remember when the first issue came out. 2 The Throw In (Unless you’re the teacher!) 3 General News This is the 50th Issue of The Green and White … a story that began in 1996 and is still being told three times a year. 4 Interview with John Allen It was the best of times …. Limerick had just defeated Tipperary 5 Meet Maurice Horan 5 to be crowned champions of Munster for the second time in 3 years. 6 Sarsfield Cup And the worst of times ….. Ciarán Carey’s team lost agonisingly to 8 Code of Good Practice for Young Players Wexford in the All Ireland final of that year, and Brian Tobin had a 9 Limerick Stars in Action goal disallowed for no obvious reason. The wait for the return of the 10 Larkin Shield Liam McCarthy Cup goes on. There were no computers or interactive whiteboards in class- 12 The Limerick GAA Club Draw rooms in those days. -

2008 AFL Annual Report

PRINCIPLES & OUTCOMES MANAGING THE AFL COMPETITION Principles: To administer our game to ensure it remains the most exciting in Australian sport; to build a stronger relationship with our supporters by providing the best sports entertainment experience; to provide the best facilities; to continue to expand the national footprint. Outcomes in 2008 ■■ Attendance record for Toyota AFL ■■The national Fox Sports audience per game Premiership Season of 6,511,255 compared was 168,808, an increase of 3.3 per cent to previous record of 6,475,521 set in 2007. on the 2007 average per game of 163,460. ■■Total attendances of 7,426,306 across NAB ■■The Seven Network’s broadcast of the 2008 regional challenge matches, NAB Cup, Toyota AFL Grand Final had an average Toyota AFL Premiership Season and Toyota national audience of 3.247 million people AFL Finals Series matches was also a record, and was the second most-watched TV beating the previous mark of 7,402,846 set program of any kind behind the opening in 2007. ceremony of the Beijing Olympics. ■■ For the eighth successive year, AFL clubs set a ■■ AFL radio audiences increased by five membership record of 574,091 compared to per cent in 2008. An average of 1.3 million 532,697 in 2007, an increase of eight per cent. people listened to AFL matches on radio in the five mainland capital cities each week ■■The largest increases were by North Melbourne (up 45.8 per cent), Hawthorn of the Toyota AFL Premiership Season. (33.4 per cent), Essendon (28 per cent) ■■The AFL/Telstra network maintained its and Geelong (22.1 per cent). -

Killarney Outlook May Edition

Vol. 19 : Edition 21 : Friday 22nd May 2020 : www.killarneyoutlook.com @killoutlook TO ADVERTISE CALL: DES 087 6593427 | E: [email protected] TO ADVERTISE CALL: CINDY 087 1210959 | E: [email protected] Open for business, Eagers Newsagents on High Street, most popular for their Ice Cream Cones, Coffee, Lotto, picking up your weekly Killarney Outlook and an ‘all new social distancing chat’ for regular customer Joan Mangan. Eagers is back open 8-6 Mon-Sat & 9-5 on Sundays. L-R Joan Mangan, Elaine O’Connor & Owner Pat Duggan. PICTURE MARIE CARROLL-O’SULLIVAN 22.05.20 1 ADVERTISINGADVERTISING TO ADVERTISE CALL: DES 087 6593427 | E: [email protected] ADVERTISINGADVERTISING TO ADVERTISE CALL: DES 087 6593427 | E: [email protected] ADVERTISING listing. omissions or incorrect errors, for any responsible cannot be held Ltd Publications Outlook correct, everypublished is While the information effortto ensure has been made Ltd. Outlook designs and listings is held by Publications of the graphics, Copyright The 066 7142179. Tel: Castleisland. Road, Tralee Ltd., Outlook by Publications Disclaimer: Published Disclaimer: Published by Outlook Publications Ltd., Tralee Road, Castleisland. Tel: 066 7142179. The Copyright of the graphics, designs and listings is held by Outlook Publications Ltd. While every effort has been made to ensure the information published is correct, Outlook Publications Ltd cannot be held responsible for any errors, omissions or incorrect listing. omissions or incorrect errors, for any responsible cannot be held Ltd Publications Outlook correct, everypublished is While the information effortto ensure has been made Ltd. Outlook designs and listings is held by Publications of the graphics, Copyright The 066 7142179. -

Sydney Swans

; I [IJ l ~ 1-4 '+., ~ " ""'I ...s i Ii- ~ E-- QBE SYDNEY SWANS The DBE Sydney Swans and Face in the crowd AFL (NSW/ACT) Commission ,, Proudly Present NSW/ACT Watch a game and win a watch """" The Sydney -- IS THIS YOU? Each week our photographer will snap a Bro1Atnlo1At Medal Dinner face in the crowd at one of the Sydney AFL games. Venue: The New Randwick Pavilion All you have to do is check the inside back Royal Randwick Race Course page each week and if you see yourself looking back then you are the weekly Date: Monday 28 August 2000 winner. Time: 6:30pm for 7pm Just ring Nicola Cheesman on 9955 1722 by NEXT FRIDAY and send in some photo Price: $120 plus GST per person ID to claim your great prize. $1200 plus GST per table of ten You'll win a AFL club Splash watch of your choice from DSV Merchandising. Dress: Lounge suit/cocktail The splash watch is water resistant to 50 This week's winner: For booking forms and enquires please contact Monique George on 9339 9196 metres and features a dynamic graphic of If this is you, your favourite AFL team logo. It comes contact Nicola Cheesman or email [email protected] with a two year warranty and is available now from most What's New stores in on 9955 1722 Sydney. to claim your prize. Friday Night Action Sydney AFL FOOTBALL Enjoy Sydney Swans Y Western Suburbs Fr~~ I '1 m -0 I ~ !:J -- Spec i aI Guest Tony Lockett ~ · ~~ , ~ .,, SYDNEY AFL RECORD Round 16, July 22-23 2000 What's on in the AFL? All games 2.00pm unless otherwise indicated The latest news from the AFL (NSW/ACT) NSW/ACT STATE U16 TEAM IN CAMP AT WAGGA The team was selected after the four day camp. -

Afl Canberra Edition 07 $2.50

AFL CANBERRA EDITION 07 $2.50 MEDIA RELEASE: DAIRY FARMERS PARK DEADLY DUO : BELCONNEN’S UNDERWOOD BROTHERS A CHAMPION TEAM... IS BETTER THaN A inside In the Box with the GM 4 AFL Canberra Limited Bradman Stand Manuka Oval Manuka Circle ACT 2603 TEAM OF CHAMPIONS News 5 PO Box 3759, Manuka ACT 2603 Ph 02 6228 0337 Fax 02 6232 7312 Seniors 12-19 Publisher Coordinate Communication PO Box 1975 WODEN ACT 2606 Reserves 20 Ph 02 6162 3600 Email [email protected] Neither the editor, the publisher nor AFL Canberra Under 18’s 21 accepts liability of any form for loss or harm of any type however caused All design material in the magazine is copyright protected and cannot be reproduced without the written permission of Coordinate Communication. Editor Jamie Wilson Ph 02 6162 3600 Round 07 Email [email protected] Designer Logan Knight Ph 02 6162 3600 Email [email protected] vs Photography Andrew Trost Email [email protected] Greenway Oval, Sat 24th May, 2pm vs Ainslie Oval, Sun 25th May, 2pm vs Manuka Oval, Sun 25th May, 2pm Design + Branding + PR + Advertising + Internet www.coordinate.com.au In the box with the GM david wark For most of us the last couple of weeks has been a The next phase will be to introduce an AFL chance to catch our breath, do a little reviewing and Canberra song that will be used in all our a little planning. presentations that involve sound, at club games, on our website and possibly for download as a ring You may have seen the recommencement of our tone for your mobile phone. -

Sydney AFL Football Record

~ I..> ~ ~ rn 1-. ~ .... ~..... · ~ ~ ~ ~ 'i-.> ~- ., .. ~ Ii= 'i-.>...., ~ t: , (ft -c •11111 (ft • ~- ..~ -c a. fD -c ... •Ill ..~ ... fD m ...-· -51 ;:-c -c .. Ill . at (ft . I: - =- -c -- I:~ ... ::I -c;-. - 2 -· I: ◄ ... :I ::I "'"' -c (ft •◄ - fD "' ~- --c ca . -◄ . ..... fD .... 0 ·• ■ ::I ::r .w "'.... ..... fD .._.o■- flll OfD . -c . w ...... ....... WU) --= ::I 0 :r = .. (ft (ft -=-:I Ill I: ::I =:r 11:s- I' 0 flll ..I: "' .. .. fD ... 0~- "' ,. ,. :I .,,...,, ..........,,. ,_..,_ -.Q.,t''J,<;•"··• ''. -- ~' .. ___ r••• .•.••--~.....- Syd·ney AFl FiKture What's on in the AFL? All games 2.00pm unless otherwise indicated The latest news from the AFL (NSW/ACT) t NSW/ACT \iff:"' , St George 17.15(117) v Eagles 9.10(64) Round 11 Sun 23rd July Nth Shore 8 10(58) v P/Hills 18.17(125) Fri 16th June North Shore v Western Suburbs (GI Tne Sydney AFL representative team was The dates are: Sun 14th May Sydney Swans v North Shore (N) 7:30pm East Coast Eag les v Ba lmain IR) I announced last Monday night. May 20/21: Round robin : UNSW/ES 68(44) v Swans 18.16(124) Sat 17th June St George v UNSW/ES (0) The 30-man sq uad will travel to Wagga Summerland/Tamworth/North Coast/Central P/Hills 133(81) v Nth Shore 17.11(113) UNSW/ES v Campbelltown IV) BYE: Campbelltown Wagga to take on the Riverina side at Maher West in Tamworth Sun 9th April BYE Western Suburbs Sun 18th June Swans 21.23(149) v UN SW/ES 5 9(39) Western Suburbs v St George (WI Round 17 Oval from 1.30pm on June 10th. -

Sydney AFL Football Record

al~" ;....} ...:I~ ~ ~ l1 " Face in the crowd Friday Night Action Watch a game and win a watch IS THIS YOU? Each week our photographer will snap a face in the crowd at one of the Sydney AFL Sydney AFL games. All you have to do is check the inside back page each week and if you see yourself looking back then you are the weekly winner. Just ring Nicola Cheesman on 9955 1722 FOOTBALL by NEXT FRIDAY and send in some photo ID to claim your great prize. You'll win a AFL club Splash watch of your choice from DSV Merchandising. The splash watch is water resistant to 50 This week's winner: metres and features a dynamic graphic of If this is you, your favourite AFL team logo. It comes contact Nicola Cheesman with a two year warranty and is available now from most What's New stores in on 9955 1722 Sydney. to claim your prize. Balma1n Y Sydney Swans For your club's chance to WIN a FREE POWERaDE Kit, complete Friday July 14 • J. 3 Opm with 2 barrels, 30 bottles, 2 runner's bags and 200 litres of Mee1 Cyanatius Swan • Free Face Paintina POWERaDE, simply place an order with Coe.a-Cola before July 14. WIN • Be a Swans Masco1 for a day iaffl ti Fii11a:a Coca-Cola Amatil (Aust) Pty Ltd has special rates for all AFL (NSW/ACT) clubs and every carton you purchased also earns your club points that can be exchanged for Coca-Cola branded merchandise at the end of the season - great for auction or raffle items. -

Greg Williams Bernard Toohey Barry Mitchell Mark Bayes Dennis Carroll

Dane Rampe Jake Lloyd Craig Bird Lewis Jetta Lance Franklin Sam Reid Ben McGlynn Rhyce Shaw Nick Malceski Harry Cunningham Ted Richards Martin Mattner Luke Parker Herbie Matthews Josh Kennedy Nick Smith Mike Pyke Dan Hannebery Kieren Jack Jack Hacker Billy King Ted Johnson Joe Scanlan Bill Windley Gary Rohan Heath Grundy Jack Graham Jim Cleary Reg Richards Harry Lampe Bert Howson Jarrad McVeigh Paul Williams Stephen Wright Matthew Nicks Barry Hall Rod Carter Ian Roberts Ben Mathews Amon Buchanan Luke Ablett Tadhg Kennelly Darren Jolly Tony Morwood Dennis Carroll Bernard Toohey Barry Mitchell Greg Williams Craig Bolton Jared Crouch Michael OLoughlin Paul Bevan Colin Hounsell Bernie Evans Leon Higgins David Murphy Jude Bolton Brett Kirk Lewis Roberts-Thomson Ryan OKeefe Nic Fosdike David Ackerly Anthony Daniher Mark Bayes Barry Round Adam Goodes Leo Barry Graham Teasdale Mark Browning Jason Saddington Brad Seymour Daniel McPherson Daryn Cresswell Jim Taylor Hec McKay Harry Clarke Terry Brain Troy Luff Paul Kelly Dale Lewis Greg Lambert Bob Skilton Gary Brice Peter Bedford Ricky Quade Ron Clegg William Williams Ron Hillis Peter Reville Austin Robertson Bill Faul Stuart Maxfield Andrew Dunkley Greg Stafford Brian McGowan John Heriot Russell Cook David McLeish Bob Pratt John Austin Len Thomas Norm Goss Steve Hoffman Reg Gleeson Jim Caldwell Arthur Hiskins Len Mortimer John Rantall Paul Harrison Bob Deas Bill Thomas Mark Tandy Joe Prince Vic Belcher. -

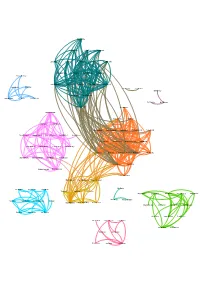

Late Submission with Permission

Cardiff Metropolitan University | Prifysgol Fetropolitan Caerdydd LATE SUBMISSION WITH PERMISSION (MARK TO BE RECORDED AS FIRST ATTEMPT) Student Name: George Brown Student Number: 20001590 Programme: SES Year: 3 Term: 2 (Spring) Module Number & Title: SSP6050 Independent Project Original Submission Date: 21 March 2014 Date extension requested: 24/01/2014 Programme Director: Rich Neil Date agreed by PD: 04/02/2014 New Submission Date: 17 April 2014 Note: A completed copy of this form must be attached to your dissertation. Both dissertation and form must be submitted by the ‘new submission date’. Failure to do so will result in a maximum mark of 40% as a second attempt. Cardiff School of Sport DISSERTATION ASSESSMENT PROFORMA: Empirical 1 Student name: George Brown Student ID: 20001590 Programme: SES Dissertation title: Comparing Gaelic football to the determinants of winning performance in Australian Rules football Supervisor: Darrell Cobner Comments Section Title and Abstract (5%) Title to include: A concise indication of the research question/problem. Abstract to include: A concise summary of the empirical study undertaken. Introduction and literature review (25%) To include: outline of context (theoretical/conceptual/applied) for the question; analysis of findings of previous related research including gaps in the literature and relevant contributions; logical flow to, and clear presentation of the research problem/ question; an indication of any research expectations, (i.e., hypotheses if applicable). Methods and Research Design (15%) To include: details of the research design and justification for the methods applied; participant details; comprehensive replicable protocol. Results and Analysis (15%) 2 To include: description and justification of data treatment/ data analysis procedures; appropriate presentation of analysed data within text and in tables or figures; description of critical findings.