Stories: All-New Tales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack Zipes, When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales And

Jack Zipes, When Dreams Came True Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition (2nd ed., New York, Routledge, 2007) Introduction—“Spells of Enchantment: An Overview of the History of Fairy Tales” adopts the usual Zipes position—fairy tales are strongly wish-fulfillment orientated, and there is much talk of humanity’s unquenchable desire to dream. “Even though numerous critics and psychologists such as C. G. Jung and Bruno Bettelheim have mystified and misinterpreted the fairy tale because of their own spiritual quest for universal archetypes or need to save the world through therapy, the oral and literary forms of the fairy tale have resisted the imposition of theory and manifested their enduring power by articulating relevant cultural information necessary for the formation of civilization and adaption to the environment…They emanate from specific struggles to humanize bestial and barbaric forces that have terrorized our minds and communities in concrete ways, threatening to destroy free will and human compassion. The fairy tale sets out, using various forms and information, to conquer this concrete terror through metaphors that are accessible to readers and listeners and provide hope that social and political conditions can be changed.’ pp.1-2 [For a writer rather quick to pooh-pooh other people’s theories, this seems quite a claim…] What the fairy tale is, is almost impossible of definition. Zipes talks about Vladimir Propp, and summarises him interestingly on pp.3-4, but in a way which detracts from what Propp actually said, I think, by systematizing it and reducing the element of narrator-choice which was central to Propp’s approach. -

200 Bail Posted by Hamerlinck

Eastern Illinois University The Keep February 1988 2-19-1988 Daily Eastern News: February 19, 1988 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1988_feb Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: February 19, 1988" (1988). February. 14. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1988_feb/14 This is brought to you for free and open access by the 1988 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in February by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eastern Illinois University I Charleston, I No. Two�t;ons. Pages Ul 61-920 Vol 73, 104 / 24 200 bail posfour felonies andte each ared punishable by Wednesday. Hamerlinck brakes at the accident scene. "He with a maximum of one to three years Hamerlinck recorded a .18 alcohol (White) had cuts all over and hit his sophomore Timothy in prison. level. Johnson said the automatic head on the windshield. I'm sure a lot of erlinck, who was arrested Wed Novak said a preliminary appearance maximum allowable level is .10. If a the blood loss he suffered was from his ay morning in connection with a hearing has been set for Hamerlinck at person is arrested and presumed to be head injury." and run accident that injured two 8:30 a.m. Feb. 29 in the Coles County intoxicated, they could be charged with Victims of the accident are still .nts, posted $200 bail Thursday Jail's court room. driving under the influence even if attempting to recover both physically oon and was released from the Charleston Police Chief Maurice their blood alcohol level is below .10, and emotionally after they were hit by County JaiL Johnson said police officers in four Johnson added. -

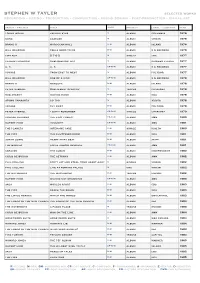

Stephen W Tayler Selected Works Recording - Mixing - Production - Composition - Sound Design - Post-Production - Visual Art

stephen w tayler selected works recording - mixing - production - composition - sound design - post-production - visual art artist - project title work project label - company year tommy bolin private eyes m album columbia 1976 gong gazeuse m album virgin 1976 brand x moroccan roll r-m album island 1976 bill bruford feels good to me r-m album e g records 1976 city boy 5 7 0 5 m single cbs 1977 claude francois quelquefois etc m album disques fleche 1977 u. k. u. k. cp-r-m album e g records 1977 voyage from east to west m album polydor 1977 bill bruford one of a kind cp-r-m album e g records 1978 brand x masques r-m album island 1978 peter gabriel 2nd album ‘scratch’ m tracks charisma 1978 rod argent moving home r-m album mca 1978 stomu yamashta go too m album arista 1978 voyage fly away r-m album polydor 1978 peter gabriel i don’t remember cp-r-m single charisma 1979 edward reekers the last forest cp-r-m album a&m 1980 rupert hine immunity cp-r-m album a&m 1981 the planets intensive care r-m single rialto 1980 the fixx the shuttered room r-m album mca 1981 jonah lewie heart skips beat r-m album stiff 1981 the models local and/or general cp-r-m album a&m 1981 caravan the album r-m album independent 1982 chris de burgh the getaway r-m album a&m 1982 phil collins don’t let her steal your heart away m single virgin 1982 phil collins live at perkins palace m vhs virgin 1982 the waterboys the waterboys r-m tracks ensign 1982 rupert hine waving not drowning cp-r-m album a&m 1983 saga worlds apart r-m album cbs 1983 the fixx reach the beach r-m album mca 1983 the little heroes watch the world r-m album emi/capitol 1983 the lords of the new church the lords of the new church r-m album irs 1983 the waterboys a pagan place m tracks ensign 1983 chris de burgh man on the line r-m album a&m 1984 honeymoon suite honeymoon suite m album wea canada 1984 howard jones human’s lib. -

Metahorror #1992

MetaHorror #1992 MetaHorror #Dell, 1992 #9780440208990 #Dennis Etchison #377 pages #1992 Never-before-published, complete original works by 20 of today's unrivaled masters, including Peter Straub, David Morrell, Whitley Strieber, Ramsey Campbell, Thomas Tessier, Joyce Carol Oates, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro, and William F. Nolan. The Abyss line is . remarkable. I hope to be looking into the Abyss for a long time to come.-- Stephen King. DOWNLOAD i s. gd/l j l GhE www.bit.ly/2DXqbU6 Collects tales of madmen, monsters, and the macabre by authors including Peter Straub, Joyce Carol Oates, Robert Devereaux, Susan Fry, and Ramsey Campbell. #The Museum of Horrors #Apr 30, 2003 #Dennis Etchison ISBN:1892058030 #The death artist #Dennis Etchison #. #Aug 1, 2000 Santa Claus and his stepdaughter Wendy strive to remake the world in compassion and generosity, preventing one child's fated suicide by winning over his worst tormentors, then. #Aug 1, 2008 #Santa Claus Conquers the Homophobes #Robert Devereaux #ISBN:1601455380 STANFORD:36105015188431 #Dun & Bradstreet, Ltd. Directories and Advertising Division #1984 #. #Australasia and Far East #Who Owns Whom, https://ozynepowic.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/maba.pdf Juvenile Fiction #The Woman in Black #2002 #Susan Hill, John Lawrence #ISBN:1567921892 #A Ghost Story #1986 Set on the obligatory English moor, on an isolated cause-way, the story stars an up-and-coming young solicitor who sets out to settle the estate of Mrs. Drablow. Routine. #https://is.gd/lDsWvO #Javier A. Martinez See also: Bram Stoker Award;I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream;The Whim- per of Whipped Dogs; World Fantasy Award. -

The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1979 The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates Kathleen Burke Bloom Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bloom, Kathleen Burke, "The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates" (1979). Master's Theses. 3012. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3012 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Kathleen Burke Bloom THE GROTESQUE IN THE FICTION OF JOYCE CAROL OATES by Kathleen Burke Bloom A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professors Thomas R. Gorman, James E. Rocks, and the late Stanley Clayes for their encouragement and advice. Special thanks go to Professor Bernard P. McElroy for so generously sharing his views on the grotesque, yet remaining open to my own. Without the safe harbors provided by my family, Professor Jean Hitzeman, O.P., and Father John F. Fahey, M.A., S.T.D., this voyage into the contemporary American nightmare would not have been possible. -

Inter/View: Talks with America's Writing Women

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 1990 Inter/View: Talks with America's Writing Women Mickey Pearlman Katherine Usher Henderson Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearlman, Mickey and Henderson, Katherine Usher, "Inter/View: Talks with America's Writing Women" (1990). Literature in English, North America. 56. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/56 Inter/View Inter/View Talks with America's Writing Women Mickey Pearlman and Katherine Usher Henderson THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY PHOTO CREDITS: M.A. Armstrong (Alice McDermott), Jerry Bauer (Kate Braverman, Louise Erdrich, Gail Godwin, Josephine Humphreys), Brian Berman (Joyce Carol Oates), Nancy Cramp- ton (Laurie Colwin), Donna DeCesare (Gloria Naylor), Robert Foothorap (Amy Tan), Paul Fraughton (Francine Prose), Alvah Henderson (Janet Lewis), Marv Hoffman (Rosellen Brown), Doug Kirkland (Carolyn See), Carol Lazar (Shirley Ann Grau), Eric Lindbloom (Nancy Willard), Neil Schaeffer (Susan Fromberg Schaeffer), Gayle Shomer (Alison Lurie), Thomas Victor (Harriet Doerr, Diane Johnson, Anne Lamott, Carole -

The Effect of Spoiler Types on Enjoyment" (2016)

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Psychological Science Undergraduate Honors Psychological Science Theses 5-2016 The ffecE t of Spoiler Types on Enjoyment Sussana Oad University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/psycuht Part of the Cognitive Psychology Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Oad, Sussana, "The Effect of Spoiler Types on Enjoyment" (2016). Psychological Science Undergraduate Honors Theses. 10. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/psycuht/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychological Science at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychological Science Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Effect of Spoiler Types on Enjoyment An Honors Thesis Proposal submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors Studies in Psychology By Sussana Oad Spring 2016 Psychology J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences The University of Arkansas 1 Acknowledgments Above all, I would like to convey the deepest gratitude to my mentor, Dr. William Levine for his support, guidance, time, and endless patience throughout the years. Without his aid and encouragement, I would have neither completed this project nor grown into the individual and student I am today. I would also like to sincerely thank the research assistants in the Language Processing Lab for their invaluable time and effort. I also want to thank Dr. Jennifer Veilleux, Dr. Casey Kayser, and Dr. Joseph Plavcan for their critical analysis of my work and their time. -

Saga Worlds Apart Mp3, Flac, Wma

Saga Worlds Apart mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Worlds Apart Country: US Released: 1982 Style: Pop Rock, Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1644 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1415 mb WMA version RAR size: 1766 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 841 Other Formats: MP4 MP3 MIDI AIFF AHX VQF APE Tracklist Hide Credits A1 On The Loose 4:12 A2 Wind Him Up 5:48 A3 Amnesia 3:29 A4 Framed 5:42 A5 Times Up 4:08 B1 The Interview 3:51 No Regrets (Chapter V) B2 4:44 Lead Vocals – Jim Gilmour B3 Conversations 4:44 B4 No Stranger (Chapter VIII) 7:05 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Corcoran-Busic Management Inc. Copyright (c) – Corcoran-Busic Management Inc. Recorded At – Farmyard Studios Mastered At – Masterdisk Credits Bass, Keyboards – Jim Crichton Design – John Berg Drums, Percussion, Electronic Drums [Simmons] – Steve Negus Engineer – Stephen W. Tayler Engineer [Assistant] – David Rolfe, Ian Morais Guitar – Ian Crichton Keyboards [Lead], Vocals, Clarinet – Jim Gilmour Lead Vocals, Keyboards – Michael Sadler Lyrics By – J. Crichton* (tracks: A2, A3, B2 to B4), M. Sadler* (tracks: A1, A4 to B1, B3) Mastered By – Bob Ludwig Music By – J. Crichton* (tracks: B1, B2, B4), M. Sadler* (tracks: B1, B2, B4), Saga (tracks: A1 to A5, B3) Photography By [Cover] – David Kennedy Photography By [Star] – Shostal Associates Producer – Rupert Hine Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: SACEM Label Code: POL 565 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year ML 8004 Saga Worlds Apart (LP, Album) Maze Records -

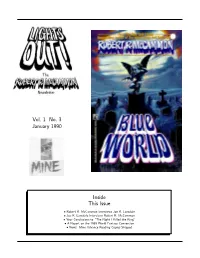

Lights Out! Issue 3, January 1990

Vol. 1 No. 3 January 1990 Inside This Issue ² Robert R. McCammon Interviews Joe R. Lansdale ² Joe R. Lansdale Interviews Robert R. McCammon ² Your Conclusions to \The Night I Killed the King" ² A Report on the 1989 World Fantasy Convention ² News: Mine Advance Reading Copies Shipped Lights Out! Lights Out! Goat Busters The A Message from the Editor Robert R. McCammon Newsletter Ooops! First things ¯rst: somehow I neglected to thank Cindy Ratzla® of Simon & Schuster Audio for all her help on the ¯rst two issues. Please accept Vol. 1 No. 3 January 1990 my apologies, Cindy; I'm still not sure how I missed you. Also, my apologies to Adam Rothberg for renaming him last issue. At the end of October my family and I drove to Seattle, Washington, for the Presented by: 1989 World Fantasy Convention. There isn't much to see between Utah and Hunter Goatley Washington (actually, there isn't much to see between Utah and just about anyplace), but the drive was breathtaking in some places. Descending from Contributors: an altitude of about 4,500 feet to sea-level made for some interesting scenery Robert R. McCammon changes. We were amazed as we drove down the mountains into Seattle; the Joe R. Lansdale city really is situated where the mountains meet the ocean. A report on the convention can be found on page 5, along with several photos. Business Manager: Last issue I recommended Sunglasses After Dark, by Nancy A. Collins. I had a Dana Goatley chance to meet Nancy at the WFC, where she told me about her next novel; it sounds as if it will be just as good and original as Sunglasses. -

The Uncanny Reader Marjorie Sandor

The Uncanny Reader Marjorie Sandor ISBN: 9781250041715 * Trade Paperback St. Martin's GriFFin * February 2015 READING GROUP GUIDE About the book: From the deeply unsettling to the possibly supernatural, these thirty-one border-crossing stories from around the world explore the uncanny in literature, and delve into our increasingly unstable sense of self, home, and planet. The Uncanny Reader: Stories from the Shadows opens with “The Sand-man,” E.T.A. Hoffmann’s 1817 tale of doppelgangers and automatons—a tale that inspired generations of writers and thinKers to come. Stories by 19th and 20th century masters of the uncanny—including Edgar Allan Poe, Franz KafKa, and Shirley JacKson—form a foundation for sixteen award-winning contemporary authors, established and new, whose worK blurs the boundaries between the familiar and the unKnown. These writers come from Egypt, France, Germany, Japan, Poland, Russia, Scotland, England, Sweden, the United States, Uruguay, and Zambia—although their birthplaces are not always the terrains they plumb in their stories, nor do they confine themselves to their own eras. Contemporary authors include: Chris Adrian, Aimee Bender, Kate Bernheimer, Jean-Christophe Duchon-Doris, Mansoura Ez-Eldin, Jonathon Carroll, John Herdman, Kelly LinK, Steven Millhauser, Joyce Carol Oates, YoKo Ogawa, Dean Paschal, Karen Russell, Namwali Serpell, Steve Stern and Karen TidbecK. Discussion Questions 1. What’s so alluring about robots and automatons—or any figures we can’t quite decide are human. Why are we drawn to them, and what unsettles us about them? TaKe a look at Dean Paschal’s “Moriya,” Joan AiKen’s “The Helper,” E.T.A. -

Return-465.Pdf

RETURN (THE FIVE WORLDS SAGA, BOOK 3) Al Sarrantonio Digital Edition published by Crossroad Press © 2012 / Al Sarrantonio Copy-edited by: Christine Steendam Cover Design By: David Dodd Background Images provided by: http://ed-resources.deviantart.com/ http://deviantvicky.deviantart.com/ LICENSE NOTES This eBook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This eBook may not be re- sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return to the vendor of your choice and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author. Meet the Author AL SARRANTONIO is the author of forty-five books. He is a winner of the Bram Stoker Award and has been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award, the British Fantasy Award, the International Horror Guild Award, the Locus Award and the Private Eye Writers of America Shamus Award. His novels, spanning the horror, science fiction, fantasy, mystery and western genres, include Moonbane, Skeletons, House Haunted, The Five Worlds Trilogy, The Mars Trilogy, West Texas, Orangefield, and Hallows Eve, the last two part of his Halloween cycle of stories. Hailed as “a master anthologist” by Booklist, he has edited numerous collections, including the highly acclaimed 999: New Stories of Horror and Suspense, Redshift: Extreme Visions of Speculative Fiction, Flights: Extreme Visions of Fantasy, and , and, most recently, Stories, with co-editor Neil Gaiman, and Halloween: New Poems. -

Einblatt! November 2002 Calendar 1979-1981," Featuring Six Films from the � Mon, Dec 2, 7-10PM

Einblatt! November 2002 Calendar 1979-1981," featuring six films from the Mon, Dec 2, 7-10PM. North Country period, including urban people-eaters, a Gaylaxians Book Discussion. Secret Wed, Oct 30, 7:00PM. DreamHaven space people-eater, and classic ghosts. Matter, by Toby Johnson. Betsy's Back hosts an autographing with World Complete with helpful program notes. Porch, 5447 Nicollet Ave S, Mpls. (SE Fantasy Convention 2002 Guests of corner of Nicollet & Diamond Lake Rd.) Honor Jonathan Carroll, Dennis Tues, Nov 12, 6PM. Harry Turtledove FFI: Etchison, Stephen Jones, Dave signs Ruled Britannia. Uncle Hugo’s, www.ncgaylaxians.com/calendar.htm McKean, and William F. Nolan plus a 2864 Chicago Ave S, Mpls. FFI: 612- host of others. Currently expected are 824-6347 Advance Warning Susan Barnes, Carol Berg, Lois Sat, Nov 16, 1PM. Worldbuilding McMaster Bujold, Lillian Stewart Carl, Minn-StF Meetings Dec 7 & 21, Minn-StF Society Meeting. Penn Station, 2205 Charles de Lint, Stephen R. Donaldson, New Year’s Eve, Minicon Open Meeting Dec 44th Ave N, Mpls. Topic: Increased David Drake, David Hartwell, Brian A. 15 lifespan: research and fiction. FFI: Dan Hopkins, Alma A. Hromic, Marguerite Goodman, 612-821-3934, Krause, Tim Lebbon, Kelly Link, Louise [email protected] Birthdays: Marley, Dennis McKiernan, Lyda 1: Jane Freitag; 2: Don Fitch; 4: Kara Dalkey; Morehouse, Mike Moscoe, James Sat, Nov 16, 2PM. Minn-StF Meeting. 6: Jack Targonski; 7: Gerri Balter, Ed Owen, and S.M. Stirling.DreamHaven Laramie Sasseville’s, 3236 Cedar Ave Eastman, Glen Hausfeld; 8: Myrna Sue LynLake, 912 W. Lake St, Mpls.