And Wordsworth's “Intimations Ode”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Visionary Company

WILLIAM BLAKE 49 rible world offering no compensations for such denial, The] can bear reality no longer and with a shriek flees back "unhinder' d" into her paradise. It will turn in time into a dungeon of Ulro for her, by the law of Blake's dialectic, for "where man is not, nature is barren"and The] has refused to become man. The pleasures of reading The Book of Thel, once the poem is understood, are very nearly unique among the pleasures of litera ture. Though the poem ends in voluntary negation, its tone until the vehement last section is a technical triumph over the problem of depicting a Beulah world in which all contraries are equally true. Thel's world is precariously beautiful; one false phrase and its looking-glass reality would be shattered, yet Blake's diction re mains firm even as he sets forth a vision of fragility. Had Thel been able to maintain herself in Experience, she might have re covered Innocence within it. The poem's last plate shows a serpent guided by three children who ride upon him, as a final emblem of sexual Generation tamed by the Innocent vision. The mood of the poem culminates in regret, which the poem's earlier tone prophe sied. VISIONS OF THE DAUGHTERS OF ALBION The heroine of Visions of the Daughters of Albion ( 1793), Oothoon, is the redemption of the timid virgin Thel. Thel's final griefwas only pathetic, and her failure of will a doom to vegetative self-absorption. Oothoon's fate has the dignity of the tragic. -

Saving America from the Radical Left COVER the Radical Left Nearly Succeeded in Toppling the United States Republic

MAY-JUNE 2018 | THETRUMPET.COM Spiraling into trade war Shocking Parkland shooting story you have not heard Why U.S. men are failing China’s great leap toward strongman rule Is commercial baby food OK? Saving America from the radical left COVER The radical left nearly succeeded in toppling the United States republic. MAY-JUNE 2018 | VOL. 29, NO. 5 | CIRC.262,750 (GARY DORNING/TRUMPET, ISTOCK.COM/EUGENESERGEEV) We are getting a hard look at just what the radical left is willing to do in order to TARGET IN SIGHT seize power and President-elect Donald Trump meets with stay in power. President Barack Obama in the Oval Office in November 2016. FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 1 FROM THE EDITOR 18 INFOGRAPHIC 28 WORLDWATCH COVER STORY A Coming Global Trade War Saving America From the Radical 31 SOCIETYWATCH Left—Temporarily 20 China’s Great Leap Toward Strongman Rule 33 PRINCIPLES OF LIVING 4 1984 and the Liberal Left Mindset The Best Marriage Advice in 22 What Will Putin Do With Six More the World 6 The Parkland Shooting: The Years of Power? Shocking Story You Have Not Heard 34 DISCUSSION BOARD 26 Italy: Game Over for Traditional 10 Why American Men Are Failing Politics 35 COMMENTARY America’s Children’s Crusade 13 Commercial Baby Food: A Formula for Health? 36 THE KEY OF DAVID TELEVISION LOG 14 Spiraling Into Trade War Trumpet editor in chief Gerald Trumpet executive editor Stephen News and analysis Regular news updates and alerts Flurry’s weekly television program Flurry’s television program updated daily from our website to your inbox theTrumpet.com/keyofdavid theTrumpet.com/trumpet_daily theTrumpet.com theTrumpet.com/go/brief FROM THE EDITOR Saving America From the Radical Left—Temporarily People do not realize just how close the nation is to collapse. -

William Blake 1 William Blake

William Blake 1 William Blake William Blake William Blake in a portrait by Thomas Phillips (1807) Born 28 November 1757 London, England Died 12 August 1827 (aged 69) London, England Occupation Poet, painter, printmaker Genres Visionary, poetry Literary Romanticism movement Notable work(s) Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, The Four Zoas, Jerusalem, Milton a Poem, And did those feet in ancient time Spouse(s) Catherine Blake (1782–1827) Signature William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form "what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language".[1] His visual artistry led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced".[2] In 2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[3] Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham[4] he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as "the body of God",[5] or "Human existence itself".[6] Considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, Blake is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work. His paintings William Blake 2 and poetry have been characterised as part of the Romantic movement and "Pre-Romantic",[7] for its large appearance in the 18th century. -

Images of the Divine Vision in the Four Zoas

Oberlin Digital Commons at Oberlin Honors Papers Student Work 1973 Nature, Reason, and Eternity: Images of the Divine Vision in The Four Zoas Cathy Shaw Oberlin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Shaw, Cathy, "Nature, Reason, and Eternity: Images of the Divine Vision in The Four Zoas" (1973). Honors Papers. 754. https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors/754 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Digital Commons at Oberlin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Oberlin. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATURE, nEASON, and ETERNITY: Images of the Divine Vision in The }1'our Zoas by Cathy Shaw English Honors }i;ssay April 26,1973 In The Four Zoas Blake wages mental ,/Ur against nature land mystery, reason and tyranny. As a dream in nine nights, the 1..Jorld of The Four Zoas illustrates an unreal world which nevertheless represents the real t-lorld to Albion, the dreamer. The dreamer is Blake's archetypal and eternal man; he has fallen asleep a~ong the floitlerS of Beulah. The t-lorld he dreams of is a product of his own physical laziness and mental lassitude. In this world, his faculties vie 'tvi th each other for pOi-vel' until the ascendence of Los, the imaginative shapeI'. Los heralds the apocalypse, Albion rem-Jakas, and the itwrld takes on once again its original eternal and infinite form. -

New Night Thoughts Sightings First Noticed by Bentley in 1980

MINUTE PARTICULAR was desperate for cash, the presence of any plates and other potentially lucrative bibliographic details are carefully not- ed in both categories. It is possible, therefore, that the cat- alogue describes the unillustrated state of Night Thoughts, 6 New Night Thoughts Sightings first noticed by Bentley in 1980. Whether or not this is the case, Mills did know at least one of the Edwardses, and his bookplate is found in a copy of Junius’s Stat nominis umbra, By Wayne C. Ripley 2 vols. (London: T. Bensley, 1796-97), with the inscription “1796 B[ough]t. of Edwards.”7 As Bentley notes, the ini- Wayne C. Ripley ([email protected]) is an associ- tials “J / E”, James Edwards, appear on the inner front cov- ate professor of English at Winona State University in er of the unillustrated Night Thoughts. As my discovery of Minnesota. He is the co-editor of Editing and Reading the advertisements for volume 2 suggests, James may have been more involved in the production and distribution of Blake with Justin Van Kleeck for Romantic Circles. He 8 has written on Blake and Edward Young. the book than has been recognized. Unfortunately, if Mills did, in fact, own the unillustrated copy, the sales catalogue explains neither why he did so nor why the copy was creat- ed in the first place. 1 O my list of catalogue references to Blake’s Night T Thoughts, which was augmented by G. E. Bentley, Jr.,1 3 The second new listing occurs in A Catalogue of Books, for should be added eight new listings. -

William Blake's Method Of

Interfaces Image Texte Language 39 | 2018 Gestures and their Traces “Printing in the infernal method”: William Blake’s method of “Illuminated Printing” Michael Phillips Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/489 DOI: 10.4000/interfaces.489 ISSN: 2647-6754 Publisher: Université de Bourgogne, Université de Paris, College of the Holy Cross Printed version Date of publication: 1 July 2018 Number of pages: 67-89 ISSN: 1164-6225 Electronic reference Michael Phillips, ““Printing in the infernal method”: William Blake’s method of “Illuminated Printing””, Interfaces [Online], 39 | 2018, Online since 01 July 2018, connection on 07 January 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/interfaces/489 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/interfaces.489 Les contenus de la revue Interfaces sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. 67 “PRINTING IN THE INFERNAL METHOD”: WILLIAM BLAKE’S METHOD OF “ILLUMINATED PRINTING” Michael Phillips University of York In 1788 William Blake invented what was technically a revolutionary method of printing both word and image together that he called “Illuminated Printing”. Blake’s invention made it possible to print both the text of his poems and the images that he created to illustrate them from the same copper plate, by etching both in relief (in contrast to conventional etching or engraving in intaglio). This allowed Blake to print his books in “Illuminated Printing” on his own copper-plate rolling-press. Significantly, this meant that he became solely responsible not only for the creation, but also for the reproduction of his works, and largely free from commercial constraint and entirely free from censorship. -

The Ambiguity of “Weeping” in William Blake's Poetry

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1968 The Ambiguity of “Weeping” in William Blake’s Poetry Audrey F. Lytle Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Liberal Studies Commons, and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Commons Recommended Citation Lytle, Audrey F., "The Ambiguity of “Weeping” in William Blake’s Poetry" (1968). All Master's Theses. 1026. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1026 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~~ THE AMBIGUITY OF "WEEPING" IN WILLIAM BLAKE'S POETRY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Education by Audrey F. Lytle August, 1968 LD S77/3 I <j-Ci( I-. I>::>~ SPECIAL COLL£crtoN 172428 Library Central W ashingtoft State Conege Ellensburg, Washington APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ________________________________ H. L. Anshutz, COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN _________________________________ Robert Benton _________________________________ John N. Terrey TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION 1 Method 1 Review of the Literature 4 II. "WEEPING" IMAGERY IN SELECTED WORKS 10 The Marriage of Heaven and Hell 10 Songs of Innocence 11 --------The Book of Thel 21 Songs of Experience 22 Poems from the Pickering Manuscript 30 Jerusalem . 39 III. CONCLUSION 55 BIBLIOGRAPHY 57 APPENDIX 58 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION I. -

William Blake and Sexuality

ARTICLE Desire Gratified aed Uegratified: William Blake aed Sexuality Alicia Ostriker Blake/Ae Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 16, Issue 3, Wieter 1982/1983, pp. 156-165 PAGH 156 BLAKE AS lLLUSTHMLD QUARTERLY WINTER 1982-83 Desire Gratified and Ungratified: William Blake and Sexuality BY ALICIA OSTRIKEK To examine Blake on sexuality is to deal with a many-layered But Desire Gratified thing. Although we like to suppose that everything in the Plants fruits of life & beauty there (E 465) canon "not only belongs in a unified scheme but is in accord What is it men in women do require? with a permanent structure of ideas,"1 some of Blake's ideas The lineaments of Gratified Desire clearly change during the course of his career, and some What is it Women do in men require? others may constitute internal inconsistencies powerfully at The lineaments of Gratified Desire (E 466) work in, and not resolved by, the poet and his poetry. What It was probably these lines that convened me to Blake I will sketch here is four sets of Blakean attitudes toward sex- when I was twenty. They seemed obviously true, splendidly ual experience and gender relations, each of them coherent symmetrical, charmingly cheeky —and nothing else I had read and persuasive if not ultimately "systematic;" for conven- approached them, although I thought Yeats must have pick- ience, and in emulation of the poet's own method of per- ed up a brave tone or two here. Only later did I notice that the sonifying ideas and feelings, I will call them four Blakes. -

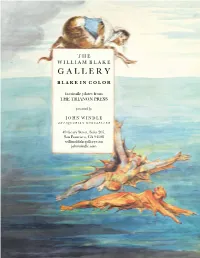

G a L L E R Y B L a K E I N C O L O R

T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E I N C O L O R facsimile plates from THE TRIANON PRESS presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 williamblakegallery.com johnwindle.com T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y TERMS: All items are guaranteed as described and may be returned within 5 days of receipt only if packed, shipped, and insured as received. Payment in US dollars drawn on a US bank, including state and local taxes as ap- plicable, is expected upon receipt unless otherwise agreed. Institutions may receive deferred billing and duplicates will be considered for credit. References or advance payment may be requested of anyone ordering for the first time. Postage is extra and will be via UPS. PayPal, Visa, MasterCard, and American Express are gladly accepted. Please also note that under standard terms of business, title does not pass to the purchaser until the purchase price has been paid in full. ILAB dealers only may deduct their reciprocal discount, provided the account is paid in full within 30 days; thereafter the price is net. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 233 San Francisco, CA 94108 T E L : (415) 986-5826 F A X : (415) 986-5827 C E L L : (415) 224-8256 www.johnwindle.com www.williamblakegallery.com John Windle: [email protected] Chris Loker: [email protected] Rachel Eley: [email protected] Annika Green: [email protected] Justin Hunter: [email protected] -

![Articles "Blake, Thomas Boston, and the Fourfold Vision" (Blake 19 [1986]: 142) and "'W —M Among the Footnotes That Irritate Me Most (I Shall Call](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0753/articles-blake-thomas-boston-and-the-fourfold-vision-blake-19-1986-142-and-w-m-among-the-footnotes-that-irritate-me-most-i-shall-call-2530753.webp)

Articles "Blake, Thomas Boston, and the Fourfold Vision" (Blake 19 [1986]: 142) and "'W —M Among the Footnotes That Irritate Me Most (I Shall Call

MINUTE PARTICULAR The Orthodoxy of Blake Footnotes Michael Ferber Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 32, Issue 1, Summer 1998, pp. 16-19 If any readers in 1830 considered these affinities between The Orthodoxy of Blake Footnotes Blake and Hogg, they may also have recalled the cryptic allusion to "W — m B — e, a great original," in the ending BY MICHAEL FERBER of Hogg's greatest novel, six years earlier.22 Yet in spite of tempting evidence, none of the reviews of Cunningham in the Edinburgh Literary Journal can be proved he disheartening experience of reading the footnotes to to be Hogg's. The most that may safely be claimed is that TBlake's poems in recent student anthologies has Hogg probably saw, and enJoyed, those reviews, and he prob- launched little theories in my head. Is it a case of horror vacuP. ably read their comments on Blake. Like some readers of Some annotators seem unable to let a proper name go by the Journal, he may also have noticed the similarities be- without attaching an "explanation" to it; any explanation tween himself and Blake which that passage seems to sug- will serve, it seems, but preferably an "etymology." Or is it gest. the return of the repressed? Many of these notes have been refuted or strongly questioned for many years now. Is it a medieval deference to "authority"? If so, it is a selective def- erence, only to those with a loud, confident manner, such as Harold Bloom. Is it mere laziness? We need a note on "north- ern bar" so let's see what the last couple of anthologies said about it .. -

The Book of Thel

Colby Quarterly Volume 23 Issue 2 June Article 4 June 1987 The Function of Dialogue in The Book of Thel Harriet Kramer Linkin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 23, no.2, June 1987, p.66-76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Linkin: The Function of Dialogue in The Book of Thel The Function of Dialogue in The Book of Thel by HARRIET KRAMER LINKIN N The Book ofThel the series of exchanges Thel shares with the pastoral I creatures of Har constitute a dialogic pattern that breaks down at a sig nificant moment in the text; Blake creates and then disrupts the pattern to provide an interpretive hermeneutic for the reader. 1 By examining the function - and dysfunction - of dialogue we gain useful insights into what most critics consider Thel's imaginative failure to pass from Inno cence through Experience to Organized Innocence. 2 Although readers sometimes blame Thel's flight from the land unknown on the presumably inadequate information she receives from her three mentors in the vale the Lilly, the Cloud, and the Clod - Thel is not really as passive a listener as she is generally accused of being: the contrary responses Thel voices qualify the applicability of her instructors' words. 3 Because she shares only a surface likeness to her mentors, she finds an easy excuse to dismiss their offerings; I believe her interactions teach Thel a useful strategy, however, that she neglects to adopt when she reaches the land unknown. -

A Reply to Irene Chayes

DISCUSSION A Reply to Irene Chayes John Beer Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 4, Issue 4, Spring 1971, pp. 144-147 144 Page 61 In TLS 13 September 1957, 547, Kathleen Raine asked if anyone could i- dentify the source of the quotation from Dryden on this page of the Note-Book, "At length for hatching ripe he breaks the shell." Just in case she never received an an- swer, Blake is quoting Fables Ancient and Modem, "Palamon and Arcite," Bk. Ill, line 1069. Page 72 Compare the sketch to the figure running over the waves on the title page Of Visions of the Daughters of Albion. Page 74 The woman standing over a supine child, upper left, is the preliminary for the same figures above the text of "Holy Thursday" in songs of Experience. I suspect that this volume will be rendered nearly useless when Erdman's new fac- simile edition of the Note-Book appears from the Clarendon Press (announced in Blake Newsletter, Fall, 1970, p. 36). Until then, the reprint is all we have available. DISCUSSION "With intellectual spears, & long winged arrows of thought" JOHN BEER: PETERHOUSE, CAMBRIDGE A Reply to Irene Chayes Since my letter replying to John E. Grant appeared alongside a review of Blake's vision- ary universe [see the Blake Newsletter, 4 (Winter 1971), 87-90] which raises further points about my reading of Blake's visual designs, I should like to renew the discussion briefly. I was disappointed that Mrs. Chayes reviewed the illustrations and the section of commentary in isolation instead of (as I had hoped) studying both in the context of the book s argument, but this approach is consistent with her general "direct" view of Blake's art.