Bestial Rape from Greek Myth to Jim Carrey: Comedian Comedies and the Heroic Rapist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beneficence of Gayface Tim Macausland Western Washington University, [email protected]

Occam's Razor Volume 6 (2016) Article 2 2016 The Beneficence of Gayface Tim MacAusland Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation MacAusland, Tim (2016) "The Beneficence of Gayface," Occam's Razor: Vol. 6 , Article 2. Available at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu/vol6/iss1/2 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occam's Razor by an authorized editor of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MacAusland: The Beneficence of Gayface THE BENEFICENCE OF GAYFACE BY TIM MACAUSLAND In 2009, veteran funny man Jim Carrey, best known to the mainstream within the previous decade with for his zany and nearly cartoonish live-action lms like American Beauty and Rent. It was, rather, performances—perhaps none more literally than in that the actors themselves were not gay. However, the 1994 lm e Mask (Russell, 1994)—stretched they never let it show or undermine the believability his comedic boundaries with his portrayal of real- of the roles they played. As expected, the stars life con artist Steven Jay Russell in the lm I Love received much of the acclaim, but the lm does You Phillip Morris (Requa, Ficarra, 2009). Despite represent a peculiar quandary in the ethical value of earning critical success and some of Carrey’s highest straight actors in gay roles. -

Paul Rudd Strikes a Comedic Pose While Bowling for Children Who Stutter

show ad Funnyman with a heart of gold! Paul Rudd strikes a comedic pose while bowling for children who stutter By Shyam Dodge PUBLISHED: 03:33 EST, 22 October 2013 | UPDATED: 03:34 EST, 22 October 2013 30 View comments He's known for being one of the funniest men working in Hollywood today. But Paul Rudd proved he's also got a heart of gold as he hosted his second annual All-Star Bowling Benefit for children who stutter in New York, on Monday. The 44-year-old actor could be seen throughout the fund raising event performing various comedic antics while bowling at the lanes. Gearing up: Paul Rudd hosted his second annual All-Star Bowling Benefit for children who stutter in New York, on Monday The I Love You, Man star taught some of the fundamentals of the sport to the children gathered for the event. But when it came his turn to demonstrate his bowling prowess it appeared he may have needed some practise in the art. Performing a comedic kick in the air after seeming to land the ball in the gutter the surrounding kids erupted into both applause and giggles. Getting a rise: The 44-year-old actor looked to have missed his mark during the event The set up: Rudd got his form down before letting loose But the antics also seemed to have been choreographed to entertain the youngsters, who the star was intent upon helping. Wearing brown suede loafers and tan chinos, Rudd went casual in a simple chequered button down shirt. -

180-TFM153.Feat Btoe

T H E A - Z O F C O M E D Y B Is for... British comedy and the Boat that rocked... ... starring Nick Frost, out of the Wright/Pegg comfort zone and into Richard Curtis' sure-to-be hit comedy. WORDS MATT MUELLER “I don’t like watching comedy,” Even Frost admits it’s as soft-centred and declares Nick Frost. “I know that gooey as Curtis’ previous labours. “What makes me sound like a miserable old else do you expect from bastard but I just don’t.” a Richard Curtis film? This is the most Filling, as he does, the second slot in uncynical, nicest piece of cinema that the comedy A-Z, it’s only natural to you’ll probably see this year. It’s lovely. question the burly funnyman on his own And I managed to watch it without just particular heroes of British comedy during thinking, ‘Oh fuck, I look fat.’” his youth in Essex. “The thing is,” Frost Curtis, an admirer of Hot Fuzz and Shaun continues, “I was a very different person as Of The Dead, wrote the part of cretinous a kid. I only watched slasher pics. When DJ Dave for Frost. “I was tremendously mum and dad were in the pub, they’d let touched,” the actor enthuses. “He’s British me go and hire Halloween or Friday The comedy’s headmaster! And he wrote in a 13th. The first time I remember laughing love scene with Gemma Arterton. Thank like an idiot was The Young Ones. So that you very much, Richard Curtis! We can’t and Blackadder, I guess.” really mention Quantum Of Solace in my And now? “I try not to watch any comedy. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

Famous People with ADHD

Famous People with ADHD Here’s a list of famous people with ADHD. People on the list who lived a long time ago weren’t officially diagnosed with ADHD, but their written history suggests they might have had ADHD. Enjoy the list. You are in good company! Will Smith…actor, singer Jim Carrey…comedian, actor Paris Hilton...actress James Carvel…political analyst Ansel Adams…photographer Pete Rose…Major League Baseball player Glenn Beck…conservative TV and radio personality Michael Phelps…Olympic swimmer Howie Mandell…comedian, actor David Neeleman…founder of Jet Blue Airways Paul Orfalea… founder of Kinko’s John F. Kennedy…U.S. President Jamie Oliver…British celebrity chef Whoopi Goldburg…comedian, actress Justin Timberlake…singer, actor Terry Bradshaw…former Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Karina Smirnoff…Ukranian professional dancer on Dancing with the Stars Sir Richard Branson…British founder of Virgin Airlines Erin Brockovich-Ellis…legal clerk and activist Ty Pennington…TV personality Scott Eyre…Major League Baseball player Frank Lloyd Wright…architect Bruce Jenner…Olympic athlete Michelle Rodriguez…actress Solange Knowles…singer (Beyonce’s little sister) Charles Schwab…financial expert Greg Louganis… Olympic swimmer Dustin Hoffman…actor Walt Disney…founder of Disney Productions Robin Williams…comedian, actor Steve Jobs…founder of Apple Computers Woody Harrelson…actor Prince Charles…future King of England John Denver…musician Dwight D. Eisenhower… U.S. President, military general Nelson Rockefeller…U.S. Vice President Beethoven…German composer Lewis Carroll…British author of Alice in Wonderland Henry Ford…automobile innovator John Lennon…British musician, member of The Beatles George Bernard Shaw…Irish author Pablo Picasso…Spanish Cubist artist Jackie Stewart…Scottish race car driver Anna Eleanor Roosevelt… U.S. -

1 Reading Athenaios' Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition And

Reading Athenaios’ Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition and Commentaries DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Corey M. Hackworth Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Fritz Graf, Advisor Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Carolina López-Ruiz 1 Copyright by Corey M. Hackworth 2015 2 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo that was found at Delphi in 1893, and since attributed to Athenaios. It is believed to have been performed as part of the Athenian Pythaïdes festival in the year 128/7 BCE. After a brief introduction to the hymn, I provide a survey and history of the most important editions of the text. I offer a new critical edition equipped with a detailed apparatus. This is followed by an extended epigraphical commentary which aims to describe the history of, and arguments for and and against, readings of the text as well as proposed supplements and restorations. The guiding principle of this edition is a conservative one—to indicate where there is uncertainty, and to avoid relying on other, similar, texts as a resource for textual restoration. A commentary follows, which traces word usage and history, in an attempt to explore how an audience might have responded to the various choices of vocabulary employed throughout the text. Emphasis is placed on Athenaios’ predilection to utilize new words, as well as words that are non-traditional for Apolline narrative. The commentary considers what role prior word usage (texts) may have played as intertexts, or sources of poetic resonance in the ears of an audience. -

Read Book ^ Titans: Atlas, Titan, Rhea, Helios, Eos, Prometheus, Hecate

[PDF] Titans: Atlas, Titan, Rhea, Helios, Eos, Prometheus, Hecate, Oceanus, Metis, Mnemosyne, Titanomachy, Selene, Themis, Tethys,... Titans: Atlas, Titan, Rhea, Helios, Eos, Prometheus, Hecate, Oceanus, Metis, Mnemosyne, Titanomachy, Selene, Themis, Tethys, Theia, Iapetus, Coeus, Crius, Asteria, Epimetheus, Hyperion, Astraeus, Cron Book Review A superior quality pdf along with the font used was intriguing to read through. It can be rally exciting throgh reading through time period. You may like how the blogger create this book. (Dr. Rylee Berg e) TITA NS: ATLA S, TITA N, RHEA , HELIOS, EOS, PROMETHEUS, HECATE, OCEA NUS, METIS, MNEMOSYNE, TITA NOMA CHY, SELENE, THEMIS, TETHYS, THEIA , IA PETUS, COEUS, CRIUS, A STERIA , EPIMETHEUS, HYPERION, A STRA EUS, CRON - To download Titans: A tlas, Titan, Rhea, Helios, Eos, Prometheus, Hecate, Oceanus, Metis, Mnemosyne, Titanomachy, Selene, Themis, Tethys, Theia, Iapetus, Coeus, Crius, A steria, Epimetheus, Hyperion, A straeus, Cron PDF, you should access the web link under and save the ebook or have accessibility to other information which are have conjunction with Titans: Atlas, Titan, Rhea, Helios, Eos, Prometheus, Hecate, Oceanus, Metis, Mnemosyne, Titanomachy, Selene, Themis, Tethys, Theia, Iapetus, Coeus, Crius, Asteria, Epimetheus, Hyperion, Astraeus, Cron book. » Download Titans: A tlas, Titan, Rhea, Helios, Eos, Prometheus, Hecate, Oceanus, Metis, Mnemosyne, Titanomachy, Selene, Themis, Tethys, Theia, Iapetus, Coeus, Crius, A steria, Epimetheus, Hyperion, A straeus, Cron PDF « Our solutions was introduced with a want to serve as a total on the internet electronic digital catalogue that provides use of multitude of PDF file book assortment. You could find many kinds of e-publication and also other literatures from your paperwork database. -

Athena ΑΘΗΝΑ Zeus ΖΕΥΣ Poseidon ΠΟΣΕΙΔΩΝ Hades ΑΙΔΗΣ

gods ΑΠΟΛΛΩΝ ΑΡΤΕΜΙΣ ΑΘΗΝΑ ΔΙΟΝΥΣΟΣ Athena Greek name Apollo Artemis Minerva Roman name Dionysus Diana Bacchus The god of music, poetry, The goddess of nature The goddess of wisdom, The god of wine and art, and of the sun and the hunt the crafts, and military strategy and of the theater Olympian Son of Zeus by Semele ΕΡΜΗΣ gods Twin children ΗΦΑΙΣΤΟΣ Hermes of Zeus by Zeus swallowed his first Mercury Leto, born wife, Metis, and as a on Delos result Athena was born ΑΡΗΣ Hephaestos The messenger of the gods, full-grown from Vulcan and the god of boundaries Son of Zeus the head of Zeus. Ares by Maia, a Mars The god of the forge who must spend daughter The god and of artisans part of each year in of Atlas of war Persephone the underworld as the consort of Hades ΑΙΔΗΣ ΖΕΥΣ ΕΣΤΙΑ ΔΗΜΗΤΗΡ Zeus ΗΡΑ ΠΟΣΕΙΔΩΝ Hades Jupiter Hera Poseidon Hestia Pluto Demeter The king of the gods, Juno Vesta Ceres Neptune The goddess of The god of the the god of the sky The goddess The god of the sea, the hearth, underworld The goddess of and of thunder of women “The Earth-shaker” household, the harvest and marriage and state ΑΦΡΟΔΙΤΗ Hekate The goddess Aphrodite First-generation Second- generation of magic Venus ΡΕΑ Titans ΚΡΟΝΟΣ Titans The goddess of MagnaRhea Mater Astraeus love and beauty Mnemosyne Kronos Saturn Deucalion Pallas & Perses Pyrrha Kronos cut off the genitals Crius of his father Uranus and threw them into the sea, and Asteria Aphrodite arose from them. -

With No Catchy Taglines Or Slogans, Showtime Has Muscled Its Way Into the Premium-Cable Elite

With no catchy taglines or slogans, Showtime has muscled its way into the premium-cable elite. “A brand needs to be much deeper than a slogan,” chairman David Nevins says. “It needs to be a marker of quality.” BY GRAHAM FLASHNER ixteen floors above the Wilshire corridor in entertainment. In comedy, they have a sub-brand of doing interesting things West Los Angeles, Showtime chairman and with damaged or self-destructive characters.” CEO David Nevins sits in a plush corner office Showtime can skew male (Ray Donovan, House of Lies) and female (The lined with mementos, including a prop knife Chi, SMILF). It’s dabbled in thrillers (Homeland), black comedies (Shameless), from the Dexter finale and ringside tickets to adult dramas (The Affair), docu-series (The Circus) and animation (Our the Pacquiao-Mayweather fight, which Showtime Cartoon President). It’s taken viewers on journeys into worlds TV rarely presented on PPV. “People look to us to be adventurous,” he explores, from hedge funds (Billions) to management consulting (House of says. “They look to us for the next new thing. Everything we Lies) and drug addiction (Patrick Melrose). make better be pushing the limits of the medium forward.” Fox 21 president Bert Salke calls Showtime “the thinking man’s network,” Every business has its longstanding rivalries. Coke and Pepsi. Marvel and noting, “They make smart television. HBO tries to be more things to more DC. For its first thirty-odd years, Showtime Networks (now owned by CBS people: comedy specials, more half-hours. Showtime is a bit more interested Corporation) ran a distant second to HBO. -

He's Your Officemate, Your Favorite Virgin—And Now He's Talking to God

ID #31 ID #32 He’s your officeMAte, your fAvorite virgin—And now He’s tAlking to god. inside tHe restless Mind of Steve Carell, Hollywood’s new king of coMedy. by brooke hauser pHotogrApHs by martin scHoeller 54 Premiere July/august 2006 ID #33 ID #34 thecomeDyIssue i. “HAI-GOO-BA!” In person, nothing about Steve Carell screams, “Look at me!” He wears his short hair combed, with a side part—a style often found in men’s catalogs. He is neither tall nor short, and though he is broad-shouldered and hairy- chested, he doesn’t seem burly. With the ex- ception of his thumbs, which are cartoonishly wide and flat and appear to have been blud- geoned by a large rock (think Fred Flintstone, after an incident at the quarry), he is entirely inconspicuous. He could be your dentist, your waiter, your next-door neighbor. What Steve Carell is not is the kind of guy who is used to doing nude scenes in multimillion-dollar productions such as Evan Almighty, a spin-off from 2003’s Bruce Almighty. Sitting fully dressed in a director’s chair on a soundstage in Waynesboro, Virginia, the 42-year-old actor relives the moment a few days ago when his character, Evan Baxter, discovers the first sign that God (Morgan Freeman) has chosen him to become a modern-day Noah. Baxter embraces his new image by walking into his yard in noth- ing but his birthday suit and a long beard. “I had to wear a pouch held together by a string, not unlike the string that holds on a party mask,” Carell says, his hands folded like a second-grader’s above his lap. -

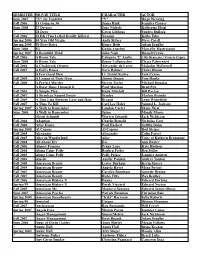

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

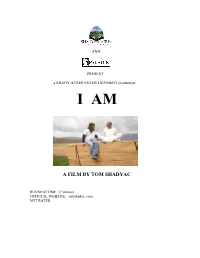

I AM Is a Prismatic, Probing, Emotionally-Charged, and Utterly

AND PRESENT a SHADY ACRES ENTERTAINMENT production I AM A FILM BY TOM SHADYAC RUNNING TIME: 77 minutes OFFICIAL WEBSITE: iamthedoc.com NOT RATED -FILM CREDITS- Written & Directed by Tom Shadyac Editor Jennifer Abbott Producer Dagan Handy Co-Produce Jacquelyn Zampella Associate Producer Nicole Pritchett Executive Producers Jennifer Abbott, Jonathan Wilson Director of Photography Roko Belic Media and PR Coordinator Harold Mintz Graphic Designer Yusuke Nagano Graphic Designer Barry Thompson “I AM” Presskit - 1 -ABOUT THE PRODUCTION- I AM is an utterly engaging and entertaining non-fiction film that poses two practical and provocative questions: what's wrong with our world, and what can we do to make it better? The filmmaker behind the inquiry is Tom Shadyac, one of Hollywood's leading comedy practitioners and the creative force behind such blockbusters as "Ace Ventura," "Liar Liar," “The Nutty Professor,” and "Bruce Almighty.” However, in I AM, Shadyac steps in front of the camera to recount what happened to him after a cycling accident left him incapacitated, possibly for good. Though he ultimately recovered, he emerged with a new sense of purpose, determined to share his own awakening to his prior life of excess and greed, and to investigate how he as an individual, and we as a race, could improve the way we live and walk in the world. Armed with nothing but his innate curiosity and a small crew to film his adventures, Shadyac set out on a twenty-first century quest for enlightenment. Meeting with a variety of thinkers and doers--remarkable men and women from the worlds of science, philosophy, academia, and faith--including such luminaries as David Suzuki, Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Lynne McTaggart, Ray Anderson, John Francis, Coleman Barks, and Marc Ian Barasch -- Shadyac appears on- screen as character, commentator, guide, and even, at times, guinea pig.