A Rational Aesthetic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Art Studies November 2020 British Art Studies Issue 18, Published 30 November 2020

British Art Studies November 2020 British Art Studies Issue 18, published 30 November 2020 Cover image: Sonia E. Barrett, Table No. 6, 2013, wood and metal.. Digital image courtesy of Bruno Weiss. PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents The Lost Cause of British Constructionism: A Two-Act Tragedy, Sam Gathercole The Lost Cause of British Constructionism: A Two- Act Tragedy Sam Gathercole Abstract This essay reflects on the demise of British constructionism. Constructionism had emerged in the 1950s, developing a socially engaged art closely aligned with post-war architecture. Its moment was not to last however, and, as discourses changed in the 1960s and 1970s, constructionism was marginalised. -

SPRING BROCHURE 2021 Sainsburycentre.Ac.Uk WELCOME to the SAINSBURY CENTRE

SPRING BROCHURE 2021 sainsburycentre.ac.uk WELCOME TO THE SAINSBURY CENTRE With spring on the way, Don’t forget to enjoy the we are looking forward to delicious eating and drinking the longer and lighter days options on offer at the ahead. Whether you’re Sainsbury Centre when we interested in exhibitions, reopen. Our new cafe, The sculptures, or just finding a Terrace, in the east end really good cup of coffee, and serves a range of Square great shopping, we have lots Mile specialty coffees for you to look forward to in alongside superb food from the coming months. local Norfolk suppliers. The Modern Life Cafe is now When we reopen, we are offering table-service only excited to share the work of with a stylish new menu. three great artists in our Bill Brandt | Henry Moore and Visitors of all ages can Grayson Perry: The Pre- enjoy our Sculpture Park Therapy Years exhibitions. and creative learning programmes, either in person We are also delighted or from the comforts of home to announce two new in our Online Studio. Visit our exhibitions opening later What’s On page to find the this year: Rhythm and latest events. Geometry: Constructivist Art in Britain since 1951 Thank you for your continued and Leiko Ikemura: Usagi in support through what has been Wonderland. a very challenging year for all. Here’s to a brighter 2021. COVER IMAGE: Grayson Perry, Essex Plate, 1985 © Grayson Perry and Victoria Miro LEFT: The Terrace cafe Photo: Andy Crouch BILL BRANDT | HENRY MOORE GRAYSON PERRY: RHYTHM AND GEOMETRY: Until Spring 2021 THE PRE-THERAPY YEARS Constructivist Art in Britain since 1951 Until Summer 2021 From Summer 2021 Explore the intersecting Organised by the Yale Center Surveying for the first time A unique opportunity to This exhibition celebrates the Marking a significant bequest paths of two great artists for British Art in partnership Grayson Perry’s earliest enjoy the artist’s clever, radical constructed abstract to the Sainsbury Centre by of the 20th century. -

Sculpture in the Home

PANGOLIN SCULPTURE IN THE HOME LONDON 1 SCULPTURE IN THE HOME One is apt to think of sculpture only as a monumental art closely connected with architecture so that the idea of an exhibition to show sculpture on a small scale as something to be enjoyed in the home equally with painting seemed worth while. Frank Dobson, Sculpture in the Home exhibition catalogue, 1946 Sculpture in the Home celebrates a series of innovative touring exhibitions of the same name organised in the 1940s and ‘50s first by the Artists International Association (AIA) and then the Arts Council. These exhibitions were intended to encourage viewers to reassociate themselves with sculpture on a smaller scale and also as an art form that could be enjoyed in a domestic environment. Works were shown not on traditional plinths or pedestals but in settings that included furniture and textiles of the day. With an estimated 2,000,000 homes destroyed by enemy action in the UK during World War II and around 60% of those in London one could be forgiven for thinking that the timing of these exhibitions was far from appropriate. However in many respects the exhibitions were perfectly timed and looking back sixty years later, offer us a unique insight into the exciting and rapid developments not only of sculpture and design but also manufacturing, and the re-establishment of the home as a sanctuary after years of hardship, uncertainty and displacement. As our exhibition hopes to explore the Sculpture in the Home exhibitions also offer us an opportunity to consider the cross-pollination between disciplines and the similarities of visual language that resulted. -

Program, Be Programmed Or Fade Away: Computers and the Death of Constructivist Art

CAT 2010 London Conference ~ 3rd February Richard Wright _____________________________________________________________________ PROGRAM, BE PROGRAMMED OR FADE AWAY: COMPUTERS AND THE DEATH OF CONSTRUCTIVIST ART Richard Wright 6 Medina Court, Seven Sisters Road, London N7 7PU U.K. [email protected] www.futurenatural.net Why did Constructivist artists of the 60s and 70s find it so hard to switch from calculators and graph paper to BASIC and PCs? Was there something in their pre-computer ‘programmatic’ ways of working that did not readily transfer to computer programming – something that could now be recovered and used to refresh current software based art practices that constantly struggle with the limitations of proprietary operating systems, desktop interfaces and network protocols? INTRODUCTION “Today we stand between a society that does not need us and one that does not yet exist.” El Lissitzky,Theo Van Doesburg and Hans Richter, “Statement by the International Faction of Constructivists”, 1922 [1]. History has not been kind to the Constructivists. Unlike the other big hitters of the Modern art movement, they have almost become figures of fun in art history – the first artist geeks with their rulers and protractors, polishing their little Perspex maquettes and planning their rectangular utopias. It seems as though Constructivism has been unable to maintain its relevance, its enthusiasm for science and engineering superseded up by the rise of mass digital computing and telecommunications. Paradoxically it feels as though Constructivism has become the victim of a kind of success story. Many of Constructivism’s core values of interdisciplinary working and research, of objective process as opposed to subjective meaning and deference to the machine as a source of artistic inspiration have now been absorbed into the assumptions of current new media art practices and funding strategies in the UK. -

World War II and After, 1940-1960 • Pop Art & Beyond, 1960-1980 • Postmodern Art, 1980-2000 • the Turner Prize • Summary

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • My sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN • The Aesthetic Movement, 1860-1880 • Late Victorians, 1880-1900 • The Edwardians, 1890-1910 • The Great War and After, 1910-1930 • The Interwar Years, 1930s • World War II and After, 1940-1960 • Pop Art & Beyond, 1960-1980 • Postmodern Art, 1980-2000 • The Turner Prize • Summary West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

CAT 2010 Ideas Before Their

2/21/12 Papers | CAT | 2010 | Conferences by year | Conference archive | eWiC - Electronic Works… Text size Contrast Home BCS Website About eWiC Contact eWiC Search this site Conference archive Publish your conference Email alert service Academic publications Your location: Conference archive Con2fe0r1eC0nAcTes Pbay pyeerasr About eWiC Papers Conference archive Browse the conference papers here Conferences by year Keynotes Session 1: Computer Art & Cybernetics 2011 Session 2: Computer Art & Time Session 3: Computer Art & Space 2010 Session 4: Computer Art & Output Session 5: Computer Art & Technocultures HCI Keynotes iUBICOM Post Computer Art - Ontological Undecidability and the Cat with Paint EVA on its Paws Brian Reffin-Smith VECOS Create10 Session 1: Computer Art & Cybernetics Digital Pioneers: Computer-generated Art from the V&A's Collections VoCS Douglas Dodds EASE Print copies of CAT 2010: Ideas The Interactive Art System before their time IHCI Stroud Cornock ISBN 978-1-906124-64-9 RRP £45 CAT Art of Conversation Ernest Edmonds and Francesca Franco Available from the BCS bookshop Papers The Computer-Generated Artworks of Vladimir Bonačić 2009 Darko Fritz 2008 Session 2: Computer Art & Time 2007 On the Relationship of Computing to the Arts and Culture - an Evolutionary Perspective 2006 George Mallen Conferences by subject Paragraphs on Computer Art, Past and Present Publish your conference Frieder Nake Email alert service Program, Be Programmed or Fade Away: Computers and the Death of Constructivist Art Academic publications Richard -

British Abstract

BRITISH108 Fine ArtABSTRACT 1 2 British Abstract Norman Adams Victor Anton Frank Beanland Trevor Bell Maurice Cockrill Alan Davie Brian Fielding Keith Grant Derrick Greaves John Hoyland Kim Lim Kenneth Martin John Plumb Iain Robertson Michael Sandle Peter Sedgley Jack Smith William Turnbull 108 FINE ART, HARROGATE, 2015 Michael Tyzack www.108fineart.com 3 Jack Smith (1928 -2011) Shimmer 3 Acrylic on canvas, 1962 48 x 48 inches (122 x 122cm) £12,000 Born in Sheffield, Jack Smith was awarded a scholarship to Sheffield College of Art 1944–6, before taking up his National Service in the R.A.F, 1946–48. He resumed studies at St Martin’s School of Art 1948–50, and at the R.C.A. 1950–53 under John Minton, Ruskin Spear and Carel Weight. At first he worked in a neo-realist style (the so-called ‘Kitchen-Sink School’), choosing subjects from the domestic life of his own home, but from 1956 he became increasingly interested in representing light and its transformatory effects on shapes seen in the open air and under water. His first one-man exhibition was held at the Beaux Arts Gallery in 1953. In 1954 he visited Madrid and Toledo, and the following year travelled to Venice. In 1956 he won first prize at the first John Moores Liverpool Exhibition. From this time onwards he began to visit Mevagissey and Zennor, Cornwall on a regular basis. From 1957 he taught at Chelsea School of Art. Jack Smith exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1956 together with Ivon Hitchens and Lynn Chadwick. -

British Art Studies November 2020 British Art Studies Issue 18, Published 30 November 2020

British Art Studies November 2020 British Art Studies Issue 18, published 30 November 2020 Cover image: Sonia E. Barrett, Table No. 6, 2013, wood and metal.. Digital image courtesy of Bruno Weiss. PDF generated on 30 November 2020 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents The Lost Cause of British Constructionism: A Two-Act Tragedy, Sam Gathercole The Lost Cause of British Constructionism: A Two- Act Tragedy Sam Gathercole Abstract This essay reflects on the demise of British constructionism. Constructionism had emerged in the 1950s, developing a socially engaged art closely aligned with post-war architecture. Its moment was not to last however, and, as discourses changed in the 1960s and 1970s, constructionism was marginalised. -

British Modern Remade — Style

20 April 2012 BRITISH MODERN REMADE — STYLE . DESIGN . GLAMOUR . HORROR Ground floor and flats 32 and 33 Norwich Street (12th floor) Park Hill Estate, Sheffield 4th May – 16 June 2012 British Modern Remade is the second project to take place as a result of Select.ac – the Arts Council Collection’s curatorial competition for postgraduate students designed to nurture the next generation of curators in the UK. The winning proposal was from Helen Kaplinsky, a student who graduated last year from the MFA in Curating at Goldsmiths College, London. British Modern Remade is an exhibition of key works drawn from the Arts Council Collection, the largest loan collection of modern and contemporary British art in the world, taking place in two show flats at the newly redeveloped Park Hill housing estate in Sheffield. The commercial and domestic setting for the Modern, postmodern and contemporary artworks underline the historical tie in Britain between style , visual art, decorative design and the hand-crafted quality of the artworks hark back to a British Arts and Crafts tradition whose ethic returned to Britain during the height of Modernism via Bauhaus. The artworks act as indicators of style and glamour in an aspirational domestic environment. Horror appears as a symptom of our uncanny relationship with style, in which something ‘out of style’ can be seen as oppositional. Tracing the meeting of decorative and visual arts in Britain back to the advent of the collection in 1946, early works by Kenneth Armitage, Lynn Chadwick and Kenneth Martin now displayed at Park Hill were featured in some of the first Arts Council Collection exhibitions of the 1940s and 1950s. -

From System to Software: Computer Programming and the Death of Constructivist Art

From System to Software: Computer Programming and the Death of Constructivist Art Richard Wright, October 2005. (Written for “White Heat, Cold Logic: British Computer Arts 1960 - 1980”, (ed.) Charlie Gere at al, Birkbeck College and MIT Press, 2006). “Today we stand between a society that does not need us and one that does not yet exist.” El Lissitzky,Theo Van Doesburg and Hans Richter, “Statement by the International Faction of Constructivists”, 1922 [1]. History has not been kind to the Constructivists. Unlike the other big hitters of the Modern art movement, they have almost become figures of fun in art history – the first artist geeks with their rulers and protractors, polishing their little Perspex maquettes and planning their rectangular utopias. One can still find artists who feel an affinity with Surrealism’s uncovering of the irrational, designers who take inspiration from Cubism’s fragmentation of space or radical intellectuals that find a precedent in the anarchic interventions of Dada. But it seems as though Constructivism has been unable to maintain its relevance to British artists since the end of the seventies, its enthusiasm for science and engineering superseded up by the rise of mass digital computing and telecommunications. In fact it feels as though Constructivism has become a victim of a kind of success story. Many of Constructivism’s core values of collaborative working and research, of objective process as opposed to subjective meaning and deference to the machine as a source of artistic inspiration have now been absorbed into the assumptions of current new media art practices and funding strategies in the UK. -

Rhythm and Geometry: Constructivist Art in Britain Since 1951

Press Release | New Exhibition 4 May 2021 Rhythm and Geometry: Constructivist art in Britain since 1951 Fritton, Mary Webb, 1971 © Mary Webb and the Sainsbury Centre Rhythm and Geometry: Constructivist art in Britain since 1951 2 October 2021 – 30 January 2022 Press View: 4 October, 12 – 2pm with light lunch. More details to follow. High-resolution images available for download: https://bit.ly/3ncjuSk Drawn from the Sainsbury Centre collection, Rhythm and Geometry: Constructivist art in Britain since 1951, celebrates the abstract and constructed art made and exhibited in Britain since 1951. The free exhibition includes work from the beginning of the 1950s to the present-day, comprising c.120 objects across sculpture, reliefs, mobiles, painting, drawing and printmaking. The exhibition examines the rise of this dramatic strand in post-war British art led by the example of Victor Pasmore, who famously converted to abstract art in the late 1940s. But it was 1951 that would prove to be a vital year for the arts in Britain. The Festival of Britain 1 was staged across the country to celebrate the arts, sciences, technology and industrial design. In the same year, the first exhibition devoted to abstract art since before the War was presented by the Artists’ International Association; Victor Pasmore and Mary Martin made their first relief sculptures, and Kenneth Martin his first mobile. Opening with a selection of significant reliefs – a pivotal art form in Britain in 1951 – the exhibition goes on to look at the transition into abstraction that occurred at this time. Process-based artworks from the 1950s will demonstrate their mathematical or scientific foundations, before charting the development into participatory or kinetic art forms. -

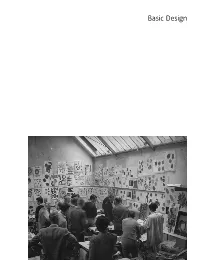

Basic Design Edited by Elena Crippa and Beth Williamson with Additional Contributions by Alexander Massouras and Hester R

Basic Design Edited by Elena Crippa and Beth Williamson With additional contributions by Alexander Massouras and Hester R. Westley First published 2013 on the occasion of the display Basic Design Curated by Elena Crippa and Beth Williamson Tate Britain, 25 March – 25 September 2013 Design by Tate Design Studio Cover image: Session of group criticism, Scarborough Summer School, Yorkshire, c.1956 Contents 6 Basic Design 14 A Chameleon and A Contradiction: From Pre-Diploma to Foundation 20 Basic Design and the Artist-Teacher 24 Basic Design and Exhibition-Making 28 Basic Colour 32 List of exhibited works 34 Further reading Basic Design Elena Crippa and Beth Williamson This display presents a turning point in the history of British art education. It explores the origins, influences and practice of ‘Basic Design’ training in British art schools through some of the artworks and artists it produced. At a time when approaches to art education are being reconsidered, it seems important to look back at historical developments such as Basic Design and review their significance both then and now. In the art schools of the 1950s in Britain, Basic Design emerged as a radical new artistic training. It emerged in response to already-existing teaching methods embodied within the skills-based National Diploma in Design and was the first attempt to create a formalised system of knowledge based on an anti-Romanticist, intuitive approach to art teaching. What actually constituted Basic Design was disputed at the time and continues to be debated now. Its contested nature is underscored by the fact that it was variously termed Basic Design, ‘Basic Form’, the ‘Basic Course’, ‘Basic Grammar’ or even ‘Basic Research’.