A Primer on Memory Reconsolidation and Its Psychotherapeutic Use As a Core Process of Profound Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dance and the Imagination an Inspiration Turned Into a Fantasy

Twelve Conceptions of Imagination – by Leslie Stevenson (1) The ability to think of something not presently perceived, but spatio‐ temporally real. (2) The ability to think of whatever one acknowledges as possible in the spatio‐temporal world. (3) The ability to think of something that the subject believes to be real, but which is not. (4) The ability to think of things that one conceives of as fictional. (5) The ability to entertain mental images. (6) The ability to think of anything at all. (7) The non‐rational operations of the mind, that is, those explicable in terms of causes rather than reasons. (8) The ability to form perceptual beliefs about public objects in space and time. (9) The ability to sensuously appreciate works of art or objects of natural beauty without classifying them under concepts or thinking of them as useful. (10) The ability to create works of art that encourage such sensuous appreciation. (11) The ability to appreciate things that are expressive or revelatory of the meaning of human life. (12) The ability to create works of art that express something deep about the meaning of life. Dance and the Imagination An inspiration turned into a fantasy based reality A dream envisioned and resourcefully staged Mental creative pictures coming to life Inventiveness using human movement in space Innovation and individuality whether improvised or more formally choreographed Expressive bodily ideas Experiential corporal representations Artistic power and ingenuity transposed into physical form Presentational musculo-skeletal -

Depotentiation of Symptom-Producing Implicit Memory in Coherence Therapy

Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 2008, in press DEPOTENTIATION OF SYMPTOM-PRODUCING IMPLICIT MEMORY IN COHERENCE THERAPY BRUCE ECKER1 AND BRIAN TOOMEY2 1Private practice in psychotherapy, Oakland, California 2Clinical Psychology Department, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee In this second of three articles we suggest criteria defining the optimal use of neuro- plasticity (synaptic change) in psychotherapy and provide a detailed examination of the use of neuroplasticity in coherence therapy. We delineate a model of how coherence therapy engages native mental processes that (a) efficiently reveal specific, symptom- generating, unconscious personal constructs in implicit emotional memory, and then (b) selectively depotentiate these constructs, ending symptom production. Both the psy- chological and the neural operation of this methodology are described, particularly how it defines and follows the built-in rules of change of the brain-mind-body system. On neuroscientific grounds we suggest a fundamental distinction between transforma- tive change, which permanently eliminates symptom-generating constructs and neural circuits, and counteractive change, which creates new constructs and circuits that compete against the symptom-generating ones and is inherently susceptible to relapse. We propose that coherence therapy achieves transformative change through the reconsolidation of memory, a recently discovered form of neuroplasticity, and present evidence consistent with this hypothesis. Subjective attention emerges as a critical agent of change in both the phenomenological and neural viewpoints, profoundly connecting these two domains. The constructivist clinical methodology now tory.2 The goal of this study was to identify the known as coherence therapy and its conceptual brain-mind-body system’s native processes and framework, coherence psychology,1 emerged from rules of change. -

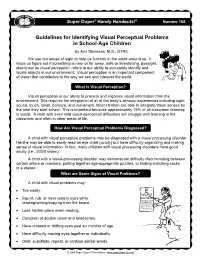

Visual Perceptual Skills

Super Duper® Handy Handouts!® Number 168 Guidelines for Identifying Visual Perceptual Problems in School-Age Children by Ann Stensaas, M.S., OTR/L We use our sense of sight to help us function in the world around us. It helps us figure out if something is near or far away, safe or threatening. Eyesight, also know as visual perception, refers to our ability to accurately identify and locate objects in our environment. Visual perception is an important component of vision that contributes to the way we see and interpret the world. What Is Visual Perception? Visual perception is our ability to process and organize visual information from the environment. This requires the integration of all of the body’s sensory experiences including sight, sound, touch, smell, balance, and movement. Most children are able to integrate these senses by the time they start school. This is important because approximately 75% of all classroom learning is visual. A child with even mild visual-perceptual difficulties will struggle with learning in the classroom and often in other areas of life. How Are Visual Perceptual Problems Diagnosed? A child with visual perceptual problems may be diagnosed with a visual processing disorder. He/she may be able to easily read an eye chart (acuity) but have difficulty organizing and making sense of visual information. In fact, many children with visual processing disorders have good acuity (i.e., 20/20 vision). A child with a visual-processing disorder may demonstrate difficulty discriminating between certain letters or numbers, putting together age-appropriate puzzles, or finding matching socks in a drawer. -

Metacognitive Awareness Inventory

Metacognitive Awareness Inventory What is Metacognition? The simplest definition of metacognition is “thinking about thinking.” This refers to the “self-regulation” effective learners exhibit, meaning they are aware of their learning process and can measure how efficiently they are learning as they study. Essentially, metacognition involves two simultaneous levels of thought: the first level is the student’s thinking/learning about the specific subject content and the second level is the student’s thinking about his/her learning. A student practicing metacognition would ask him/herself “How am I thinking?” or “Where am I in the learning process? Am I learning/understanding this topic? How could I learn more effectively?” These two levels are: knowledge and regulation. Students who are metacognitively aware demonstrate self-knowledge: They know what strategies and conditions work best for them while they are learning. Declarative, procedural, and conditional knowledge are essential for developing conceptual knowledge (content knowledge). Regulation refers to students’ knowledge about the implementation of strategies and the ability to monitor the effectiveness of their strategies. When students regulate, they are continually developing and monitoring their learning strategies based on their evolving self-knowledge. Complete the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory to assess your metacognitive processes. The Inventory Check True or False for each statement below. After you complete the inventory, use the scoring guide. Contact an Academic Coach at the Academic Support Center at (856) 681-6250 to discuss your results and strategies to increase your metacognitive awareness. True False 1. I ask myself periodically if I am meeting my goals. 2. I consider several alternatives to a problem before I answer. -

A Critical Skill for Learning Scott Barry Kaufman in Recent Years, Schools

Imagination: A Critical Skill for Learning Scott Barry Kaufman In recent years, schools have become increasingly focused on developing “executive functions” in students. These functions—which include the ability to concentrate, ignore distractions, regulate emotions, and integrate complex information in working memory—are certainly important contributors to learning. However, I believe that in our school’s excitement over executive functions, we’ve missed out on the why of education. Another class of functions have been recently discovered by cognitive neuroscientists that-- when combined with executive functioning—contribute to deep, personally meaningful learning, long-term retention, compassion, and creativity. Dubbed the “default mode network” by cognitive scientists, the following imagination-related functions have been associated with this network: daydreaming, imagining and planning the future, retrieving deeply personal memories, making meaning out of experiences, monitoring one’s emotional state, reading fiction, reflective compassion, and perspective taking. This is an important set of skills to fall by the wayside among our students! In fact, by constantly demanding the executive attention of students for the purposes of abstract learning, we are actively robbing students of the opportunity to use the limited resource of attention for the purposes of personal reflection, meaning-making, and compassionate perspective taking. Let’s be clear: both executive functions and imagination-related cognitive processes are critical to learning. However, when these networks couple together, we can get the best learning outcomes out of students. People who live a meaningful life of creativity and accomplishment combine dreaming with doing. A common thread that runs through both grit and imagination is trial-and-error: the ability to dream, to set concrete goals, to construct various strategies to reach the goal, to tinker with alternative approaches to reaching the goal, and to constantly revise approaches where necessary. -

Coherence Therapy for Depression

Case example of Coherence Therapy for Depression Website edition of an article by Bruce Ecker & Laurel Hulley first published in Psychotherapy Networker as “Deep from the Start: Profound Change in Brief Therapy is a Real Possibility” Psychotherapy Networker, 26 (1), pp. 46-51, 64 (Jan-Feb 2002) © 2007 Bruce Ecker & Laurel Hulley There is a moment that we therapists savor above all. We've just done or said something decisively effective and put our client in touch with a deep emotional reality. Before our eyes, a shift takes place--a shift in both mind and body--and the client slips from the grip of a lifelong pattern. Such breakthroughs are the heart and soul of good therapy and they give most of us our greatest sense of professional satisfaction and purpose. Yet, few therapists like to admit how infrequently they occur in the average practice, no matter what the clinical approach. In much long-term therapy, breakthrough experiences seem to come almost randomly, and then only after months or years. In briefer therapies, on the other hand, deeply rooted emotional realities are often ignored altogether in favor of "reframes" and other forms of cognitive or behavioral change. Two decades ago, seeking both depth and brevity in our clinical work, we began going over the process notes and audiotapes of thousands of our interactions with clients, especially those that yielded the most powerful turning points. What, we wondered, had happened differently in those sessions? Could we find a way to focus and organize depth-oriented therapy so that transforming moments could occur from the very first session? And could we fashion a brief therapy that could dive deep into unconscious emotional realities without sacrificing much-valued speed and focus? We discovered that what distinguished the pivotal interactions was that--whether due to serendipity, curiosity, desperation or fatigue--we had completely stopped trying to counteract, override, or prevent the client’s debilitating difficulties. -

Will It Blend? Information Systems and Computer Engineering

Will It Blend? Studying Color Mixing Perception Paulo Duarte Esperanc¸a Garcia Thesis to obtain the Master of Science Degree in Information Systems and Computer Engineering Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Daniel Jorge Viegas Gonc¸alves Prof. Dra. Sandra Pereira Gama Examination Committee Chairperson: Prof. Dr. Antonio´ Manuel Ferreira Rito da Silva Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Daniel Jorge Viegas Gonc¸alves Member of the Committee: Prof. Dr. Manuel Joao˜ Caneira Monteiro da Fonseca November 2016 Acknowledgments First, I want to thank my advisor Professor Daniel Gonc¸alves for his excellent guidance, for always having the availability to teach, help and clarify, for his enormous knowledge and expertise, and for al- ways believing in the best result possible of this Master Thesis. Then, I also want to thank my co-advisor Sandra Gama, for her more-than-valuable inputs on Information Visualization and for opening the path for this dissertation and others to come! Additionally, I would like to thank everyone which somehow contributed for this thesis to happen: everyone who participated either online, or on the laboratory sessions, specially those who did it so willingly, without looking at the rewards. Without them, there would be no validity is this thesis. I must express my very profound gratitude to my family, particularly my mother Ondina and brother Diogo, for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of study and through the process of researching and writing this thesis. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank you! Finally, to my girlfriend Margarida, my beloved partner, my shelter and support, for all the sleepless nights, sweat and tears throughout the last seven years. -

Destination Imagination Is Proud to Host Our Annual Education Conference at the Westin Park Central Hotel in Dallas, TX, July 25-26, 2014

Destination Imagination is proud to host our annual education conference at the Westin Park Central Hotel in Dallas, TX, July 25-26, 2014. This year, Ignite will feature more than 30 different workshops and learning opportunities for educators that focus on emerging trends and proven strategies for engaging students in innovative and creative learning. Below are just a few of the more than 30 sessions that will be available to educators at the Ignite 2014 Innovation for Education Conference. The Invention Experience How do you inspire and excite students in the classroom? Use the Invention Experience! In this workshop, teachers will be trained on the successful 6-step invention process used by startups and technology inventors across the world. Each workshop is a hands-on guided tour through the process of invention and entrepreneurship. Teachers will learn how to fit their existing lesson plans into an “invention mindset” and use the simple 6 step process to engage students in any content area you’re teaching! At the conclusion of the workshop, teachers will leave with an Invention Guidebook and a set of worksheets that they can use with their students that will turn any lesson plan, into a hands-on, exciting experience for students of any age! The Invention Experience was developed by two Silicon Valley education entrepreneurs with the support of Microsoft and the Lemelson Foundation. Playful Learning: Bringing Game-Based Learning to Your Classroom! Play is how we learn best. An entire world of games exists to support learning that hasn't been at a teacher’s fingertips—until now. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86288-2 - Memory in Autism Edited by Jill Boucher and Dermot Bowler Excerpt More information Part I Introduction © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86288-2 - Memory in Autism Edited by Jill Boucher and Dermot Bowler Excerpt More information 1 Concepts and theories of memory John M. Gardiner Concept. A thought, idea; disposition, frame of mind; imagination, fancy; .... an idea of a class of objects. Theory. A scheme or system of ideas or statements held as an explan- ation or account of a group of facts or phenomena; a hypothesis that has been confirmed or established by observation or experiment, and is propounded or accepted as accounting for the known facts; a statement of what are known to be the general laws, principles, or causes of some- thing known or observed. From definitions given in the Oxford English Dictionary The Oxford Handbook of Memory, edited by Endel Tulving and Fergus Craik, was published in the year 2000. It is the first such book to be devoted to the science of memory. It is perhaps the single most author- itative and exhaustive guide as to those concepts and theories of memory that are currently regarded as being most vital. It is instructive, with that in mind, to browse the exceptionally comprehensive subject index of this handbook for the most commonly used terms. Excluding those that name phenomena, patient groups, parts of the brain, or commonly used exper- imental procedures, by far the most commonly used terms are encoding and retrieval processes. -

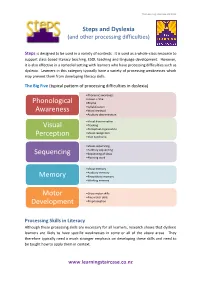

Phonological Awareness Visual Perception Sequencing Memory

The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 Steps and Dyslexia (and other processing difficulties) Steps is designed to be used in a variety of contexts. It is used as a whole-class resource to support class-based literacy teaching, ESOL teaching and language development. However, it is also effective in a remedial setting with learners who have processing difficulties such as dyslexia. Learners in this category typically have a variety of processing weaknesses which may prevent them from developing literacy skills. The Big Five (typical pattern of processing difficulties in dyslexia) •Phonemic awareness •Onset + rime Phonological •Rhyme •Syllabification Awareness •Word retrieval •Auditory discrimination •Visual discrimination Visual •Tracking •Perceptual organisation •Visual recognition Perception •Irlen Syndrome •Visual sequencing •Auditory sequencing Sequencing •Sequencing of ideas •Planning work •Visual memory •Auditory memory Memory •Kinaesthetic memory •Working memory Motor •Gross motor skills •Fine motor skills Development •Proprioception Processing Skills in Literacy Although these processing skills are necessary for all learners, research shows that dyslexic learners are likely to have specific weaknesses in some or all of the above areas. They therefore typically need a much stronger emphasis on developing these skills and need to be taught how to apply them in context. www.learningstaircase.co.nz The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 However, there are further aspects which are important, particularly for learners with literacy difficulties, such as dyslexia. These learners often need significantly more reinforcement. Research shows that a non-dyslexic learner needs typically between 4 – 10 exposures to a word to fix it in long-term memory. A dyslexic learner, on the other hand, can need 500 – 1300 exposures to the same word. -

Perceptual Imagination and Perceptual Memory: an Overview

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 04/05/2018, SPi 1 Perceptual Imagination and Perceptual Memory An Overview Fiona Macpherson The essays in this volume explore the nature of perceptual imagination and perceptual memory. How do perceptual imagination and memory resemble and differ from each other and from other kinds of sensory experience? And what role does each play in perception and in the acquisition of knowledge? These are the two central questions that the essays in this volume seek to address. One important fact about our mental lives is that sensory experience comes in (at least) three central variants: perception, imagination, and memory. For instance, we may not only see the visible appearance of a person or a building, but also recall or imagine it in a visual manner. The three types of experience share certain important features that are intimately linked to their common sensory character, many of which distinguish them from thought. Among these features are their apparent presentation of external objects or events (rather than propositions about them), their perspectival nature, that is that they present the world from a certain point of view, and their connection to one (or more) of the sense modalities, such as by having some modality- specific content and phenomenal character. But there are also important differences among the three types of sensory experiences. Most notably, there is usually taken to be a fundamental divide between perceptions, on the one hand, and recollections and imaginings, on the other. Perceptual experiences are typically taken to be distinct from imaginative and mnemonic ones in that they present objects with a certain sense of immediacy. -

The Natural Power of Intuition

THE NATURAL POWER OF INTUITION: EXPLORING THE FORMATIVE DIMENSIONS OF INTUITION IN THE PRACTICES OF THREE VISUAL ARTISTS AND THREE BUSINESS EXECUTIVES by Jessica Jagtiani Dissertation Committee: Professor Judith Burton, Sponsor Professor Mary Hafeli Approved by the Committee on the Degree of Doctor of Education Date 16 May 2018 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education in Teachers College, Columbia University 2018 ABSTRACT THE NATURAL POWER OF INTUITION: EXPLORING THE FORMATIVE DIMENSIONS OF INTUITION IN THE PRACTICES OF THREE VISUAL ARTISTS AND THREE BUSINESS EXECUTIVES Jessica Jagtiani Both artists and business executives state the importance of intuition in their professional practice. Current research suggests that intuition plays a significant role in cognition, decision-making, and creativity. Intuitive perception is beneficial to management, entrepreneurship, learning, medical diagnosis, healing, spiritual growth, and overall well-being, and is furthermore, more accurate than deliberative thought under complex conditions. Accordingly, acquiring intuitive faculties seems indispensable amid present day’s fast-paced multifaceted society and growing complexity. Today, there is an overall rising interest in intuition and an existing pool of research on intuition in management, but interestingly an absence of research on intuition in the field of art. This qualitative-phenomenological study explores the experience of intuition in both professional practices in order to show comparability and extend the base of intuition, while at the same time revealing what is unique about its emergence in art practice. Data gathered from semi-structured interviews and online-journals provided the participants’ experience of intuition and are presented through individual portraits, including an introduction to their work, their worldview, and the experiences of intuition in their lives and professional practice.