Republic of Moldova

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Finance Benchmarking Toolkit: Piloting and Lessons Learned

fdaşlığ тво East нерс рт Strengthening Institutional Frameworks ідне па tenariat Orientalteneriatul Esti for Local Governance 2015-2017 Par ar ğı P artnership P Pa fdaşlıq во Eastern r T eneriatul Estic Східне пар Local Finance tnership enariat Oriedaşl art r f q t ten fda ar r Par r Benchmarking ıq тво Easter rq t fdaşlıq P fdaşlıq r нерс во Eastern P r T рт т T нерс рт Toolkit: Східне хідне па eneriatul Estic Ş па a art eneriatultnership Estic Ş P teneriatul Estic Східне ar at Oriental Східне паOrientala r P artnership P daşlığı P enariat O artnership tenariat Ofd piloting and stern f art P ar r r q t во Eastern P r q t ст Eastern daşlıq P r fdaşlığı P во Ea r f r т T lessons learned q t тво Ea r нерс Estic iatul Estichip Ş Схід eneriatu t artnership atul Estic Ş нерс l Estic Ş eriatul Estic Par tener daşlığ Східне парт ar r f rtnership P tenariat Oriental тво Eastern P rq t ip ar с eneri ер во Східне парт t не т MOLDOVA ar daşlığı P нерс P r f eneriatul Estic Ş tners Східне парт art tenariat Oriental ar P en P LOCAL FINANCE BENCHMARKING TOOLKIT: PILOTING AND LESSONS LEARNED Східне парт t Par tnership Par Par ENG tnership tenariat Oriental n tn ar ar rtenariat OrientalP ar Eastern f P Pa во r l q Eastern ğ ern The Council of Europe is the continent’s leading human rights The European Union is a unique economic and political partnership http://eap-pcf-eu.coe.int organisation. -

A REPUBLICI MOI,DOVA BRICEI{I Nr. 6 Iiotarfue 6Tl Or.Briceni L

CON{ISIA ELECTORAL.tr, CENTRALA A REPUBLICI MOI,DOVA CONSILIUL ELECTORAL AL CIRCUMS,CEIPTIEI ELECTORALE BRICEI{I nr. 6 ALEGERILE PENTRU FUNCTIA DE PRESEDINTE AL REPUBLICtr MOLDOVA DIN I NOIEMBRIE 2||AO IIOTARfuE cu privire la constituirea sectiilor de votar€ dh,,25"s€ptembrie 2020 nr.06 ln conformitate cu acliunil€ stabilite ln Prograrnul - calendarisric, aprobat prin hotdrirea CEC w-' 4103D020, precum qi in temeiul arr. 30 gi art.l08 din codul electoral ff.13'gl/1997, consiliul electoral al circumscripfiei electorale Bric€ni nr.6, hottrrf,9te: 1.. se constituie socfiile de votare de la pinn _ nr.6/l 9i h nr.6/40 la alegerile pentu funclia de Pregedinte al Republicii Moldova din 0l noiembrie 2020, dupi cum unn€aza: Denumirea Nr. Hottr€le s€ctiei de votare Adresa sediuN Adresa localului s€qJiei de sectiei biroului electoral al pentru votare gi votarc de secliei de voae $ modul de v0tare modul de contactare contac{are peftru pentru rela{ii relafii Bdc€ni 6tl I Str.Indep€ndenlei(numerele Or,Briceni Or.Briceni I pare), st $tefan cel Mare, str- Str.Independenfei, Str.IndEpeodenlei, I la $tefrn cel Mare, 30 30 I str.M.Lermontov, st S.Lazo, Casa de Cultur{ Casa de Cultur{ I sf.Prieteniei, sh-la Prieteniei. 'lel:0247-22396 Tel:0247-22396 I st l.Turghenev, str-la I l.Turghen€v, sh,3l August | 1989, strA.Cehov, I st.A.Macnenco.str,28 Martie, str.V,Alecsandd, str.Liber6lii, str.Tinere$ii, str.L.Tomalq st.A.Pu.gkirL str.Ferarilor, str.N.Gogol, slr.A.Nocmso\', str.S.Timo$€nco, str.L.Tolstoi, str-A.Fadeev, str.Constructorilor, str.V. -

Moldova Is Strongly Marked by Self-Censorship and Partisanship

For economic or political reasons, journalism in Moldova is strongly marked by self-censorship and partisanship. A significant part of the population, especially those living in the villages, does not have access to a variety of information sources due to poverty. Profitable media still represent an exception rather than the rule. MoldoVA 166 MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2009 INTRODUCTION OVERALL SCORE: 1.81 M Parliamentary elections will take place at the beginning of 2009, which made 2008 a pre-election year. Although the Republic of Moldova has not managed to fulfill all of the EU-Moldova Action Plan commitments (which expired in February 2008), especially those concerning the independence of both the oldo Pmass media and judiciary, the Communist government has been trying to begin negotiations over a new agreement with the EU. This final agreement should lead to the establishment of more advanced relations compared to the current status of being simply an EU neighbor. On the other hand, steps have been taken to establish closer relations with Russia, which sought to improve its global image in the wake of its war with Georgia by addressing the Transnistria issue. Moldovan V authorities hoped that new Russian president Dmitri Medvedev would exert pressure upon Transnistria’s separatist leaders to accept the settlement project proposed by Chişinău. If this would have occurred, A the future parliamentary elections would have taken place throughout the entire territory of Moldova, including Transnistria. But this did not happen: Russia suggested that Moldova reconsider the settlement plan proposed in 2003 by Moscow, which stipulated, among other things, continuing deployment of Russian troops in Moldova in spite of commitments to withdraw them made at the 1999 OSCE summit. -

![Cc-Cult-Bu(2001)2A E] Cc-Cult-Bu(2001)2A](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0700/cc-cult-bu-2001-2a-e-cc-cult-bu-2001-2a-200700.webp)

Cc-Cult-Bu(2001)2A E] Cc-Cult-Bu(2001)2A

Strasbourg, 17 September 2001 [PF: CC-Cult/1erBureau/documents/CC-CULT-BU(2001)2A_E] CC-CULT-BU(2001)2A COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL CO-OPERATION CULTURE COMMITTEE Meeting of the Bureau Chisinau, 4 (9.30 a.m.) – 5 (5.00 p.m.) October 2001 (Palais de la République Bâtiment B, 2e étage Str. Nicolai lorga, 21) EUROPEAN PROGRAMME OF NATIONAL CULTURAL POLICY REVIEWS CULTURAL POLICY IN MOLDOVA REPORT OF A EUROPEAN PANEL OF EXAMINERS Item 8 of Draft Agenda Distribution: - Members of the Bureau of the Culture Committee Documents are available for consultation on the Internet page of the cultural co- operation: http://culture.coe.int, username and password: decstest. CC-CULT-BU (2001) 2A 1 DRAFT DECISION The Bureau of the CC-Cult : - took note of the experts’ report on the Cultural Policy in Moldova (CC-Cult – BU (2001)2A) and congratulated its authors for its quality; - thanked the Moldovan authorities for their invitation to hold the first meeting of the CC-Cult Bureau in Chisinau on the occasion of the national debate on the cultural policy in Moldova; - is pleased that the MOSAIC II project will contribute to the implementation of the recommendations contained in this report. 2 CC-CULT-BU (2001) 2A Membership of the Panel of Examiners Ms France Lebon, Chairperson (Belgium) Directrice, Direction Générale de la Culture, Ministère de la Communauté Francaise - Belgium Ms Maria Berza, (Romania) Formerly State Secretary for Culture – Romania, President Romanian Centre for Cultural Policy and Projects (CERC), vice-President for Romania, Pro Patrimonio Foundation -

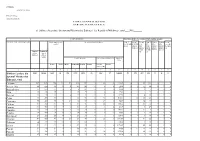

Raport Statistic 2009

Destinaţia ________________________________ _ denumirea şi adresa Cine prezintă_ denumirea şi adresa T A B E L C E N T R A L I Z A T O R D Ă R I D E S E A M Ă A N U A L E ale bibliotecilor şcolare din sistemul Ministerului Educaţiei din Republicii Moldova pe anul ___2009_______ I. DATE GENERALE Repartizarea bibliotecilor conform mărimii colecţiilor (numărul) T I P U R I D E B I B L I O T E C I Forma organizatorico- Din numărul total de biblioteci Categ. 1 Categ. 2 Categ. 3 Categ. 4 Categ. 5 Categ. 6. Categ. 7 juridică până la 2000 de la 2001 de la de la de la de la mai mult de vol. până la 5001 10.001 100.001 500.001 de 1 mln. 5000 vol până la până la până la până la 1 vol 10.000 100.000 500.000 mln. vol Numărul Numărul de vol vol total de locuri în biblioteci sălile de lectură Localul bibliotecii Starea tehnică a bibliotecilor Suprafaţa totală De stat Privată Special Reamenajat Propriu Arendat Necesită Avariat reparaţii capit. A 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Biblioteci şcolare din 1453 15845 1438 15 180 1273 1428 25 516 17 74555 29 170 431 823 0 0 0 sistemul Ministerului Educaţiei, total Chişinău 167 2839 154 13 51 116 159 8 68 1 11809 4 5 35 123 0 0 0 Anenii -Noi 36 429 36 0 5 31 36 0 6 1 2139 3 2 12 19 0 0 0 Basarabeasca 11 214 11 0 5 6 11 0 0 0 760,2 0 1 3 7 0 0 0 Bălţi 25 376 25 0 0 25 25 0 0 0 1764 0 0 1 24 0 0 0 Briceni 33 330 33 0 4 29 33 0 8 0 1327,3 3 0 4 26 0 0 0 Cahul 58 473 58 0 0 58 58 0 58 0 3023,1 1 26 10 21 0 0 0 Cantemir 35 449 35 0 21 14 35 0 29 0 1429 0 4 14 17 0 0 0 Călăraş 41 392 41 0 0 41 41 0 38 0 -

Datele De Contact Ale Serviciilor Teritoriale De Relaţii Cu Beneficiarii Ale CNAM

Datele de contact ale serviciilor teritoriale de relaţii cu beneficiarii ale CNAM Unitatea teritorial- Nr.d administrativă Adresa Telefon Programul de /o deservită lucru 1. Anenii Noi or. Anenii Noi, str. Uzinelor, nr. 30/1, bir. 38 0(265)2-21-10 08.00-17.00 (clădirea Centrului de Sănătate) pauza: 12.00-13.00 2. Basarabeasca or. Basarabeasca, str. Karl Marx, nr. 55 0(297)2-12-67 (clădirea Consiliului Raional) 08.00-17.00 pauza: 12.00-13.00 3. Bălți AT Nord a CNAM, mun. Bălți, str. Sfîntul 0(231)6-33-99 Nicolae, nr. 5A 08.00-17.00 pauza: 12.00-13.00 4. Briceni or. Briceni, str. Eminescu, nr. 48, et. 1 0(247)2-57-64 (clădirea Centrului de Sănătate) 08.00-17.00 pauza: 12.00-13.00 5. Cahul AT Sud a CNAM, or. Cahul, str. Ștefan cel 0(299)2-29-15 Mare, nr. 16 08.00-17.00 pauza: 12.00-13.00 6. Cantemir or. Cantemir, str. N.Testemiţanu, nr. 22, bir. 0(273)2-32-65 405 (clădirea Centrului de Sănătate) 08.00-17.00 pauza: 12.00-13.00 7. Călăraşi or. Călăraşi, str. Bojole, nr. 1, bir. 13 0(244)2-03-51 (clădirea Centrului de Sănătate) 08.00-17.00 pauza: 12.00-13.00 8. Căușeni AT Est a CNAM, or. Căușeni, str. Iurie 0(243)2-65-03 08.00-17.00 Gagarin, nr. 54 pauza: 12.00-13.00 9. Ceadîr-Lunga or. Ceadîr-Lunga, str. Miciurin, nr. 4 0(291)2-80-40 (clădirea Centrului de Sănătate) 08.00-17.00 pauza: 12.00-13.00 10. -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Working Paper No. WGSO-4/2007/6 Council 8 May 2007 ENGLISH ONLY ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE COMMITTEE ON ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY Ad Hoc Preparatory Working Group of Senior Officials “Environment for Europe” Fourth meeting Geneva, 30 May–1 June 2007 Item 2 (e) of the provisional agenda Provisional agenda for the Sixth Ministerial Conference “Environment for Europe” Capacity-building STRENGTHENING ENVIRONMENTAL GOVERNANCE IN THE EASTERN EUROPE, CAUCASUS AND CENTRAL ASIA THROUGH LOCAL ENVIRONMENTAL ACTION PROGRAMMES 1 Proposed category II document2 Submitted by the Regional Environmental Centers for the Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia 1 The text in this document is submitted as received from the authors. This is a draft document as of 21 April 2007. 2 Background documents (informational and analytical documents of direct relevance to the Conference agenda) submitted through the WGSO. Table of Contents Executive Summary Part I: Background A) Institutional Needs Addressed B) History of LEAPs in EECCA C) Relevance to Belgrade Conference D) Process for Preparing the Report Part II: Results to Date A) Strengthened Environmental Governance B) Improved Environmental Conditions C) Increased Long-Term Capacity Part III: Description of Activities A) Central Asia B) Moldova C) Russia D) South Caucasus Part IV: Lessons Learned and Future Directions A) Lessons Learned B) Future Directions C) Role of EECCA Regional Environmental Centers Attachment A: R E S O L U T I O N of International Conference “Local Environmental Action Plans: Experience and Achievements of EECCA RECs” Executive Summary Regional Environmental Centers (RECs) in Eastern Europe, Caucasus, and Central Asia (EECCA) have promoted local environmental action programs (LEAPs) the last five years as a means of strengthening environmental governance at the local level. -

Page | 1 FINAL REPORT June 2019 Project Financed By

P a g e | 1 ENI – European Neighbourhood Instrument (NEAR) Agreement reference No ENPI/2014/354-587 Increased opportunities and better living conditions across the Nistru/Dniestr River FINAL REPORT June 2019 Project financed by the European Union Final Report Support to Confidence Building Measures, 15 March 2015-31 December 2018 – submitted by UNDP Moldova 1 P a g e | 2 Project Title: Support to Confidence Building Measures Starting date: 15 March 2015 Report end date: 31 December 2018 Implementing agency: UNDP Moldova Country: Republic of Moldova Increased opportunities and better living conditions across the Nistru/Dniestr River ENPI/2014/354-587 Final Report (15 March 2015 - 31 December 2018) – submitted by UNDP Moldova P a g e | 3 Table of Contents I. SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................................. 4 II. CONTEXT ................................................................................................................................................ 6 III. PROGRESS UPDATE ................................................................................................................................. 7 3.1 BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT AND EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITIES ..................................................................................... 7 3.2 EMPOWERED COMMUNITIES AND INFRASTRUCTURE SUPPORT ....................................................................................... 8 IV. KEY RESULTS ....................................................................................................................................... -

Can Moldova Stay on the Road to Europe

MEMO POL I CY CAN MOLDOVA STAY ON THE ROAD TO EUROPE? Stanislav Secrieru SUMMARY In 2013 Russia hit Moldova hard, imposing Moldova is considered a success story of the European sanctions on wine exports and fuelling Union’s Eastern Partnership (EaP) initiative. In the four separatist rumblings in Transnistria and years since a pro-European coalition came to power in 2009, Gagauzia. But 2014 will be much worse. Moldova has become more pluralist and has experienced Russia wants to undermine the one remaining “success story” of the Eastern Partnership robust economic growth. The government has introduced (Georgia being a unique case). It is not clear reforms and has deepened Moldova’s relations with the whether Moldova can rely on Ukraine as a EU, completing a visa-free action plan and initialling an buffer against Russian pressure, which is Association Agreement (AA) with provisions for a Deep and expected to ratchet up sharply after the Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA). At the start Sochi Olympics. Russia wants to change the Moldovan government at the elections due in of 2014, Moldova is one step away from progressing into a November 2014, or possibly even sooner; the more complex, more rewarding phase of relations with the Moldovan government wants to sign the key EU. Implementing the association agenda will spur economic EU agreements before then. growth and will multiply linkages with Moldova’s biggest trading partner, the EU. However, Moldova’s progress down Moldova is most fearful of moves against its estimated 300,000 migrant workers in the European path promises to be one of the main focuses Russia, and of existential escalation of the for intrigue in the region in 2014. -

Pasaport 2019

RAIONUL BRICENI Președintele raionului –LupașcoVitalii Cod poștal: MD – 4700 Adresa: or.Briceni, str. Independenței 48 Anticamera – tel/fax 0(247)2 2058 Email :[email protected] Raionul Briceni –cea mai de Nord-Vest unitate administrativ-teritorială a Republicii Moldova, atestînd o treime de localități pe linia de frontieră. În partea de Nord se mărginește cu Ucraina, iar în cea de vest cu România; în partea de sud se învecinează cu raionul Edineț, iarîn partea de est – cu raionul Ocnița. Teritoriul raionului are o suprafață de 81,4 mii ha, inclusiv: - Terenuri arabile - 50,7 mii ha - Păduri - 8,2 mii ha - Bazine acvatice – 2,1 mii ha (230) iazuri - Imașuri – 6,9 mii ha - Alte terenuri – 13,5 mii ha Populația raionului constituie –73 958, inclusiv:-rurală – 60 645 -urbană – 13 313 Componența populației după naționalitate: moldoveni – 70%,ucraineni – 25 %,ruși – 1,3%, alte naționalități (minorități) 3,7%. Densitatea medie constituie 95 oameni/km2. Oraşe: Populația Briceni 8327 Lipcani 4986 Sate (comune) Localităţile din componenţalor Balasineşti Balasineşti 2359 Beleavinţi Beleavinţi 2292 Bălcăuţi 699 Bălcăuţi 676 Bocicăuți 23 Berlinţi 2005 Berlinţi 1496 CaracuşeniiNoi 509 Bogdăneşti 1201 Bogdăneşti 484 Bezeda 527 Grimeşti 190 Bulboaca Bulboaca 830 CaracuşeniiVechi CaracuşeniiVechi 4043 Colicăuţi 3001 Colicăuţi 2506 Trestieni 495 Corjeuţi Corjeuţi 7569 Coteala Coteala 1916 Cotiujeni Cotiujeni 3520 Criva Criva 1501 Drepcăuţi Drepcăuţi 2284 Grimăncăuţi Grimăncăuţi 4080 Halahora de Sus 1535 Halahora de Sus 1208 Chirilovca 12 Halahora de Jos 315 Hlina Hlina 998 Larga 4488 Larga 4471 Pavlovca 17 Mărcăuţi 1488 Mărcăuţi 1455 MărcăuţiiNoi 33 Medveja 1480 Medveja 1448 Slobozia-Medveja 32 Mihăileni 695 Mihăileni 406 Grozniţa 289 Pererita Pererita 1766 Şirăuţi Şirăuţi 2333 Slobozia-Şirăuţi Slobozia-Şirăuţi 1001 Tabani Tabani 2886 Teţcani Teţcani 2687 Trebisăuţi Trebisăuţi 1988 În componența raionului sunt 39 localități. -

Local Integration Project for Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine

LOCAL INTEGRATION PROJECT FOR BELARUS, MOLDOVA AND UKRAINE 2011-2013 Implemented by the United Nations High Funded by the European Union Commissioner for Refugees 12 June 2012 Refugees to receive apartments under EU/UNHCR scheme CHISINAU, Moldova, June 12 (UNHCR) – Four apartments rehabilitated to shelter refugees fleeing human rights abuse and conflict in their home countries have been given today to local authorities in Razeni, Ialoveni District by the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) following extensive rehabilitation works co-funded by the EU/UNHCR under the Local Integration Project (LIP) for refugees. Refugee families from Armenia, Azerbaijan and Palestine received ceremonial keys at today’s hand-over ceremony. Razeni Mayor Ion Cretu hosted Deputy Minister Ana Vasilachi (Ministry of Labour, Social Protection and the Family), Deputy Minister Iurie Cheptanaru (Ministry of Internal Affairs), Ambassador of the European Union Dirk Schübel and other dignitaries. Tuesday’s ceremony at the long-disused kindergarten follows a similar event in March when UNHCR formally handed over apartments at a former public bathhouse in Mereni, Anenii Noi District to shelter refugees from Armenia, Russia and Sudan. “Without the enthusiastic support of the mayors, council and residents of Mereni and Razeni villages, which offered the dilapidated buildings to UNHCR for renovation into apartments, this pilot refugee housing project would not have been possible,” said UNHCR Representative Peter Kessler. The refugees getting the new apartments were carefully selected based on their skills and willingness to contribute to their new host communities by a team including the Refugee Directorate of the Bureau for Migration and Asylum in the Ministry of Internal Affairs, UNHCR and its NGO implementing partners. -

Draft the Prut River Basin Management Plan 2016

Environmental Protection of International River Basins This project is implemented by a Consortium led by Hulla and Co. (EPIRB) HumanDynamics KG Contract No 2011/279-666, EuropeAid/131360/C/SER/Multi Project Funded by Ministry of Environment the European Union DRAFT THE PRUT RIVER BASIN MANAGEMENT PLAN 2016 - 2021 Prepared in alignment to the EuropeanWater Framework Directive2000/60/EC Prepared by Institute of Ecology and Geography of the Academy of Sciences of Moldova Chisinau, 2015 Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 1.General description of the Prut River Basin ................................................................................. 7 1.1. Natural conditions .......................................................................................................................... 7 1.1.1. Climate and vegetation................................................................................................................... 8 1.1.2. Geological structure and geomorphology ....................................................................................... 8 1.1.3. Surface water resources.................................................................................................................. 9 1.1.3.1. Rivers .............................................................................................................................