Oral Histories in Meteoritics and Planetary Sciencexix: Klaus Keil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

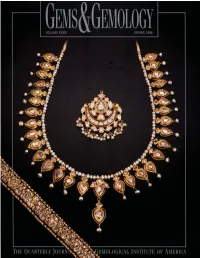

Spring 1998 Gems & Gemology

VOLUME 34 NO. 1 SPRING 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 1 The Dr. Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award FEATURE ARTICLE 4 The Rise to pProminence of the Modern Diamond Cutting Industry in India Menahem Sevdermish, Alan R. Miciak, and Alfred A. Levinson pg. 7 NOTES AND NEW TECHNIQUES 24 Leigha: The Creation of a Three-Dimensional Intarsia Sculpture Arthur Lee Anderson 34 Russian Synthetic Pink Quartz Vladimir S. Balitsky, Irina B. Makhina, Vadim I. Prygov, Anatolii A. Mar’in, Alexandr G. Emel’chenko, Emmanuel Fritsch, Shane F. McClure, Lu Taijing, Dino DeGhionno, John I. Koivula, and James E. Shigley REGULAR FEATURES pg. 30 44 Gem Trade Lab Notes 50 Gem News 64 Gems & Gemology Challenge 66 Book Reviews 68 Gemological Abstracts ABOUT THE COVER: Over the past 30 years, India has emerged as the dominant sup- plier of small cut diamonds for the world market. Today, nearly 70% by weight of the diamonds polished worldwide come from India. The feature article in this issue discuss- es India’s near-monopoly of the cut diamond industry, and reviews India’s impact on the worldwide diamond trade. The availability of an enormous amount of small, low-cost pg. 42 Indian diamonds has recently spawned a growing jewelry manufacturing sector in India. However, the Indian diamond jewelery–making tradition has been around much longer, pg. 46 as shown by the 19th century necklace (39.0 cm long), pendant (4.5 cm high), and bracelet (17.5 cm long) on the cover. The necklace contains 31 table-cut diamond panels, with enamels and freshwater pearls. -

Ernst Zinner, Lithic Astronomer

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title Ernst Zinner, lithic astronomer Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0gq43750 Journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science, 42(7/8) ISSN 1086-9379 Author Mckeegan, Kevin D. Publication Date 2007-07-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Meteoritics & Planetary Science 42, Nr 7/8, 1045–1054 (2007) Abstract available online at http://meteoritics.org Ernst Zinner, lithic astronomer Kevin D. MCKEEGAN Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California 90095–1567, USA E-mail: [email protected] It is a rare privilege to be one of the founders of an entirely new field of science, and it is especially remarkable when that new field belongs to the oldest branch of “natural philosophy.” The nature of the stars has perplexed and fascinated humanity for millennia. While the sources of their luminosity and their structures and evolution were revealed over the last century, it is thanks to the pioneering efforts of a rare and remarkable man, Ernst Zinner, as well as his colleagues and students (mostly at the University of Chicago and at Washington University in Saint Louis), that in the last two decades it has become possible to literally hold a piece of a star in one’s hand. Armed with sophisticated microscopes and mass spectrometers of various sorts, these “lithic astronomers” are able to reveal stellar processes in exquisite detail by examining the chemical, mineralogical, and especially the nuclear properties of these microscopic grains of stardust. With this special issue of Meteoritics & Planetary Science, we honor Ernst Zinner (Fig. -

Mineralogy and Petrology of the Angrite Northwest Africa 1296 Albert Jambon, Jean-Alix Barrat, Omar Boudouma, Michel Fonteilles, D

Mineralogy and petrology of the angrite Northwest Africa 1296 Albert Jambon, Jean-Alix Barrat, Omar Boudouma, Michel Fonteilles, D. Badia, C. Göpel, Marcel Bohn To cite this version: Albert Jambon, Jean-Alix Barrat, Omar Boudouma, Michel Fonteilles, D. Badia, et al.. Mineralogy and petrology of the angrite Northwest Africa 1296. Meteoritics and Planetary Science, Wiley, 2005, 40 (3), pp.361-375. hal-00113853 HAL Id: hal-00113853 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00113853 Submitted on 2 May 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 40, Nr 3, 361–375 (2005) Abstract available online at http://meteoritics.org Mineralogy and petrology of the angrite Northwest Africa 1296 A. JAMBON,1 J. A. BARRAT,2 O. BOUDOUMA,3 M. FONTEILLES,4 D. BADIA,1 C. GÖPEL,5 and M. BOHN6 1Laboratoire Magie, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, CNRS UMR 7047, case 110, 4 place Jussieu, 75252 Paris cedex 05, France 2UBO-IUEM, CNRS UMR 6538, Place Nicolas Copernic, F29280 Plouzané, France 3Service du MEB, UFR des Sciences de la Terre, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, case 110, 4 place Jussieu, 75252 Paris cedex 05, France 4Pétrologie, Modélisation des Matériaux et Processus, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, case 110, 4 place Jussieu, 75252 Paris cedex 05, France 5Laboratoire de Géochimie et Cosmochimie, Institut de Physique du Globe, CNRS UMR 7579, 4 place Jussieu, 75252 Paris cedex 05, France 6Ifremer-Centre de Brest, CNRS-UMR 6538, BP70, 29280 Plouzané Cedex, France *Corresponding author. -

Sulfide/Silicate Melt Partitioning During Enstatite Chondrite Melting

61st Annual Meteoritical Society Meeting 5255.pdf SULFIDE/SILICATE MELT PARTITIONING DURING ENSTATITE CHONDRITE MELTING. C. Floss1, R. A. Fogel2, G. Crozaz1, M. Weisberg2, and M. Prinz2, 1McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences and Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Washington University, St. Louis MO 63130, USA ([email protected]), 2American Museum of Natural History, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, New York NY 10024, USA. Introduction: Aubrites are igneous rocks thought (present only in CaS-saturated charges) has a flat REE to have formed from an enstatite chondrite-like pattern with abundances of about 0.5 x CI. precursor [1]. Yet their origin remains poorly Discussion: Oldhamite/glass D values are close to understood, at least partly because of confusion over 1 for most REE, consistent with previous results the role played by sulfides, particularly oldhamite. [4,5,6], and significantly lower than those expected CaS in aubrites contains high rare earth element based on REE abundances in aubritic oldhamite. In (REE) abundances and exhibits a variety of patterns contrast, D values for FeS are surprisingly high (from [2] that reflect, to some extent, those seen in about 0.1 to 1), given the low REE abundances of oldhamite from enstatite chondrites [3]. However, natural troilite. FeS/silicate partition coefficients experimental work suggests that CaS/silicate melt reported by [5] are somewhat lower, but exhibit a REE partition coefficients are too low to account for similar pattern. Alkali loss from the charges, the high abundances observed [4,5] and do not explain resulting in Ca-enriched glass, might provide a partial the variable patterns. -

A New Sulfide Mineral (Mncr2s4) from the Social Circle IVA Iron Meteorite

American Mineralogist, Volume 101, pages 1217–1221, 2016 Joegoldsteinite: A new sulfide mineral (MnCr2S4) from the Social Circle IVA iron meteorite Junko Isa1,*, Chi Ma2,*, and Alan E. Rubin1,3 1Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, U.S.A. 2Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California 91125, U.S.A. 3Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, U.S.A. Abstract Joegoldsteinite, a new sulfide mineral of end-member formula MnCr2S4, was discovered in the 2+ Social Circle IVA iron meteorite. It is a thiospinel, the Mn analog of daubréelite (Fe Cr2S4), and a new member of the linnaeite group. Tiny grains of joegoldsteinite were also identified in the Indarch EH4 enstatite chondrite. The chemical composition of the Social Circle sample determined by electron microprobe is (wt%) S 44.3, Cr 36.2, Mn 15.8, Fe 4.5, Ni 0.09, Cu 0.08, total 101.0, giving rise to an empirical formula of (Mn0.82Fe0.23)Cr1.99S3.95. The crystal structure, determined by electron backscattered diffraction, is aFd 3m spinel-type structure with a = 10.11 Å, V = 1033.4 Å3, and Z = 8. Keywords: Joegoldsteinite, MnCr2S4, new sulfide mineral, thiospinel, Social Circle IVA iron meteorite, Indarch EH4 enstatite chondrite Introduction new mineral by the International Mineralogical Association (IMA 2015-049) in August 2015. It was named in honor of Thiospinels have a general formula of AB2X4 where A is a divalent metal, B is a trivalent metal, and X is a –2 anion, Joseph (Joe) I. -

HEAVY WATER and NONPROLIFERATION Topical Report

HEAVY WATER AND NONPROLIFERATION Topical Report by MARVIN M. MILLER MIT Energy Laboratory Report No. MIT-EL 80-009 May 1980 COO-4571-6 MIT-EL 80-009 HEAVY WATER AND NONPROLIFERATION Topical Report Marvin M. Miller Energy Laboratory and Department of Nuclear Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 May 1980 Prepared For THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY UNDER CONTRACT NO. EN-77-S-02-4571.A000 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. Neither the United States nor the United States Department of Energy, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or useful- ness of any information, apparatus, product or process disclosed or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. A B S T R A C T The following report is a study of various aspects of the relationship between heavy water and the development of the civilian and military uses of atomic energy. It begins with a historical sketch which traces the heavy water storyfrom its discovery by Harold Urey in 1932 through its coming of age from scientific curiosity to strategic nuclear material at the eve of World War II and finally into the post-war period, where the military and civilian strands have some- times seemed inextricably entangled. The report next assesses the nonproliferation implications of the use of heavy water- moderated power reactors; several different reactor types are discussed, but the focus in on the natural uranium, on- power fueled, pressure tube reactor developed in Canada, the CANDU. -

Fe,Mg)S, the IRON-DOMINANT ANALOGUE of NININGERITE

1687 The Canadian Mineralogist Vol. 40, pp. 1687-1692 (2002) THE NEW MINERAL SPECIES KEILITE, (Fe,Mg)S, THE IRON-DOMINANT ANALOGUE OF NININGERITE MASAAKI SHIMIZU§ Department of Earth Sciences, Faculty of Science, Toyama University, 3190 Gofuku, Toyama 930-8555, Japan § HIDETO YOSHIDA Department of Earth and Planetary Science, Graduate School of Science, University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan § JOSEPH A. MANDARINO 94 Moore Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M4T 1V3, and Earth Sciences Division, Royal Ontario Museum, 100 Queens’s Park, Toronto, Ontario M5S 2C6, Canada ABSTRACT Keilite, (Fe,Mg)S, is a new mineral species that occurs in several meteorites. The original description of niningerite by Keil & Snetsinger (1967) gave chemical analytical data for “niningerite” in six enstatite chondrites. In three of those six meteorites, namely Abee and Adhi-Kot type EH4 and Saint-Sauveur type EH5, the atomic ratio Fe:Mg has Fe > Mg. Thus this mineral actually represents the iron-dominant analogue of niningerite. By analogy with synthetic MgS and niningerite, keilite is cubic, with space group Fm3m, a 5.20 Å, V 140.6 Å3, Z = 4. Keilite and niningerite occur as grains up to several hundred m across. Because of the small grain-size, most of the usual physical properties could not be determined. Keilite is metallic and opaque; in reflected light, it is isotropic and gray. Point-count analyses of samples of the three meteorites by Keil (1968) gave the following amounts of keilite (in vol.%): Abee 11.2, Adhi-Kot 0.95 and Saint-Sauveur 3.4. -

Thursday, August 11, 2016 EARLY SOLAR SYSTEM CHRONOLOGY I 8:30 A.M

79th Annual Meeting of the Meteoritical Society (2016) sess701.pdf Thursday, August 11, 2016 EARLY SOLAR SYSTEM CHRONOLOGY I 8:30 a.m. Room B Chairs: Gregory Brennecka Audrey Bouvier 8:30 a.m. Kruijer T. S. * Kleine T. Tungsten Isotope Dichotomy Among Iron Meteorite Parent Bodies: Implications for the Timescales of Accretion and Core Formation [#6449] We report new combined Pt and W isotope data for IC, IIC, IIF, IIIE, and IIIF iron meteorites, with the ultimate aim of better understanding the variable pre-exposure 182W/184W signatures observed among different iron meteorite groups. 8:45 a.m. Tissot F. L. H. * Dauphas N. Grove T. L. Heterogeneity in the 238U/235U Ratios of Angrites [#6104] We report the 238U/235U ratios of six angrites. We find that the angrite-parent body was heterogeneous with regards to U isotopes. We correct the Pb-Pb ages of angrites and test their concordance with ages derived from short-lived chronometers. 9:00 a.m. Brennecka G. A. * Amelin Y. Kleine T. Combined 238U/235U and Pb Isotopics of Planetary Core Material: The Absolute Age of the IVA Iron Muonionalusta [#6296] We report a measured 238U/235U for the IVA iron Muonionalusta. This measured value requires an age correction of ~7 Myr to the previously published Pb-Pb age. This has major implications for our understanding of planetary core formation and cooling. 9:15 a.m. Cartwright J. A. * Amelin Y. Koefoed P. Wadhwa M. U-Pb Age of the Ungrouped Achondrite NWA 8486 [#6231] We report the U-Pb age for ungrouped achondrite NWA 8486 (paired with NWA 7325). -

Origins of Life: Transition from Geochemistry to Biogeochemistry

December 2016 Volume 12, Number 6 ISSN 1811-5209 Origins of Life: Transition from Geochemistry to Biogeochemistry NITA SAHAI and HUSSEIN KADDOUR, Guest Editors Transition from Geochemistry to Biogeochemistry Staging Life: Warm Seltzer Ocean Incubating Life: Prebiotic Sources Foundation Stones to Life Prebiotic Metal-Organic Catalysts Protometabolism and Early Protocells pub_elements_oct16_1300&icpms_Mise en page 1 13-Sep-16 3:39 PM Page 1 Reproducibility High Resolution igh spatial H Resolution High mass The New Generation Ion Microprobe for Path-breaking Advances in Geoscience U-Pb dating in 91500 zircon, RF-plasma O- source Addressing the growing demand for small scale, high resolution, in situ isotopic measurements at high precision and productivity, CAMECA introduces the IMS 1300-HR³, successor of the internationally acclaimed IMS 1280-HR, and KLEORA which is derived from the IMS 1300-HR³ and is fully optimized for advanced U-Th-Pb mineral dating. • New high brightness RF-plasma ion source greatly improving spatial resolution, reproducibility and throughput • New automated sample loading system with motorized sample height adjustment, significantly increasing analysis precision, ease-of-use and productivity • New UV-light microscope for enhanced optical image resolution (developed by University of Wisconsin, USA) ... and more! Visit www.cameca.com or email [email protected] to request IMS 1300-HR³ and KLEORA product brochures. Laser-Ablation ICP-MS ~ now with CAMECA ~ The Attom ES provides speed and sensitivity optimized for the most demanding LA-ICP-MS applications. Corr. Pb 207-206 - U (238) Recent advances in laser ablation technology have improved signal 2SE error per sample - Pb (206) Combined samples 0.076121 +/- 0.002345 - Pb (207) to background ratios and washout times. -

Chondrule Sizes, We Have Compiled and Provide Commentary on Available Chondrule Dimension Literature Data

Invited review Chondrule size and related physical properties: a compilation and evaluation of current data across all meteorite groups. Jon M. Friedricha,b,*, Michael K. Weisbergb,c,d, Denton S. Ebelb,d,e, Alison E. Biltzf, Bernadette M. Corbettf, Ivan V. Iotzovf, Wajiha S. Khanf, Matthew D. Wolmanf a Department of Chemistry, Fordham University, Bronx, NY 10458 USA b Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024 USA c Department of Physical Sciences, Kingsborough College of the City University of New York, Brooklyn, NY 11235, USA d Graduate Center of the City University of New York, 365 5th Ave, New York, NY 10016 USA e Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964 USA f Fordham College at Rose Hill, Fordham University, Bronx, NY 10458 USA In press in Chemie der Erde – Geochemistry 21 August 2014 *Corresponding Author. Tel: +718 817 4446; fax: +718 817 4432. E-mail address: [email protected] 2 ABSTRACT The examination of the physical properties of chondrules has generally received less emphasis than other properties of meteorites such as their mineralogy, petrology, and chemical and isotopic compositions. Among the various physical properties of chondrules, chondrule size is especially important for the classification of chondrites into chemical groups, since each chemical group possesses a distinct size-frequency distribution of chondrules. Knowledge of the physical properties of chondrules is also vital for the development of astrophysical models for chondrule formation, and for understanding how to utilize asteroidal resources in space exploration. To examine our current knowledge of chondrule sizes, we have compiled and provide commentary on available chondrule dimension literature data. -

Physical Properties of Martian Meteorites: Porosity and Density Measurements

Meteoritics & Planetary Science 42, Nr 12, 2043–2054 (2007) Abstract available online at http://meteoritics.org Physical properties of Martian meteorites: Porosity and density measurements Ian M. COULSON1, 2*, Martin BEECH3, and Wenshuang NIE3 1Solid Earth Studies Laboratory (SESL), Department of Geology, University of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan S4S 0A2, Canada 2Institut für Geowissenschaften, Universität Tübingen, 72074 Tübingen, Germany 3Campion College, University of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan S4S 0A2, Canada *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] (Received 11 September 2006; revision accepted 06 June 2007) Abstract–Martian meteorites are fragments of the Martian crust. These samples represent igneous rocks, much like basalt. As such, many laboratory techniques designed for the study of Earth materials have been applied to these meteorites. Despite numerous studies of Martian meteorites, little data exists on their basic structural characteristics, such as porosity or density, information that is important in interpreting their origin, shock modification, and cosmic ray exposure history. Analysis of these meteorites provides both insight into the various lithologies present as well as the impact history of the planet’s surface. We present new data relating to the physical characteristics of twelve Martian meteorites. Porosity was determined via a combination of scanning electron microscope (SEM) imagery/image analysis and helium pycnometry, coupled with a modified Archimedean method for bulk density measurements. Our results show a range in porosity and density values and that porosity tends to increase toward the edge of the sample. Preliminary interpretation of the data demonstrates good agreement between porosity measured at 100× and 300× magnification for the shergottite group, while others exhibit more variability. -

Formation Mechanisms of Ringwoodite: Clues from the Martian Meteorite

Zhang et al. Earth, Planets and Space (2021) 73:165 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-021-01494-1 FULL PAPER Open Access Formation mechanisms of ringwoodite: clues from the Martian meteorite Northwest Africa 8705 Ting Zhang1,2, Sen Hu1, Nian Wang1,2, Yangting Lin1* , Lixin Gu1,3, Xu Tang1,3, Xinyu Zou4 and Mingming Zhang1 Abstract Ringwoodite and wadsleyite are the high-pressure polymorphs of olivine, which are common in shocked meteorites. They are the major constituent minerals in the terrestrial mantle. NWA 8705, an olivine-phyric shergottite, was heavily shocked, producing shock-induced melt veins and pockets associated with four occurrences of ringwoodite: (1) the lamellae intergrown with the host olivine adjacent to a shock-induced melt pocket; (2) polycrystalline assemblages preserving the shapes and compositions of the pre-existing olivine within a shock-induced melt vein (60 μm in width); (3) the rod-like grains coexisting with wadsleyite and clinopyroxene within a shock-induced melt vein; (4) the microlite clusters embedded in silicate glass within a very thin shock-induced melt vein (20 μm in width). The frst two occurrences of ringwoodite likely formed via solid-state transformation from olivine, supported by their mor- phological features and homogeneous compositions (Mg# 64–62) similar to the host olivine (Mg# 66–64). The third occurrence of ringwoodite might fractionally crystallize from the shock-induced melt, based on its heterogeneous and more FeO-enriched compositions (Mg# 76–51) than those of the coexisting wadsleyite (Mg# 77–67) and the host olivine (Mg# 66–64) of this meteorite. The coexistence of ringwoodite, wadsleyite, and clinopyroxene suggests a post- shock pressure of 14–16 GPa and a temperature of 1650–1750 °C.