Home Cooking Fires Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compact Deep Fryer CDF-100 for Your Safety and Continued Enjoyment of This Product, Always Read the Instruction Book Carefully Before Using

INSTRUCTION AND RECIPE BOOKLET Compact Deep Fryer CDF-100 For your safety and continued enjoyment of this product, always read the instruction book carefully before using. 15. Do not operate your appliance in an appliance garage or under a IMPORTANT SAFEGUARDS wall cabinet. When storing in an appliance garage always unplug the unit from the electrical outlet. Not doing so could When using electrical appliances, basic safety precautions should create a risk of fire, especially if the appliance touches the walls of always be followed, including the following: the garage or the door touches the unit as it closes. 1. READ ALL INSTRUCTIONS. 2. Unplug from outlet when not in use and before cleaning. Allow appliance and the oil to cool completely before putting on or taking off parts, and before cleaning or draining the appliance. SAVE THESE INSTRUCTIONS 3. Do not touch hot surface; use handles or knobs. FOR HOUSEHOLD USE ONLY 4. To protect against electric shock, do not immerse cord, plug or base unit in water or other liquid. 5. Close supervision is necessary when any appliance is used by or near children. 6. Do not operate any appliance with a damaged cord or plug or SPECIAL CORD SET after an appliance malfunctions, or has been damaged in any manner. Return appliance to the nearest authorized service facility INSTRUCTIONS for examination, repair or adjustment. A short power supply cord is provided to reduce the risk of becoming 7. The use of accessory attachments not recommended by entangled in or tripping over a long cord. A longer detachable power- Cuisinart may cause injuries. -

Download Catalog

Electric Appliances Product Catalogue for EUROPE Product catalogue 2019_Electric Appliances_Europe.indd 1 23/8/2019 15:15:22 Our Promise For more than a century, has consistently provided innovative, reliable, high-quality products and customer service. It’s a combination of groundbreaking technology and rock-solid dependability that’s made us one of the world’s most trusted brands. From outdoor portable generators that provide power for your home, work and play moments, to high-definition TVs that are setting new standards for performance, we’re constantly developing advanced products, rigorously testing them to make sure they work time after time, day after day. When you see the , you know you’re getting a product packed with features that make your life easier, while still being easy to use. A product that has all the latest thinking, while providing years of value. Innovation You Can Be Sure Of. From a company that always puts you first. 2 Product catalogue 2019_Electric Appliances_Europe.indd 2 23/8/2019 15:15:27 Content Heritage Time Line P.4 Museum P.6 Cooking Series Retro Series P.13 Gold Series P.16 Transform Series P.19 Culinaire Series P.20 Wooden Series P.23 Healthy Cooking Series P.24 Mini Series P.27 Fun Series P.30 Pro Series P.32 Essential Line Breakfast P.37 Blending and Juicing P.41 Mixing and Food Processing P.44 Cooking P.46 Vacuum Cleaning P.51 Home Environment P.53 3 Product catalogue 2019_Electric Appliances_Europe.indd 3 23/8/2019 15:15:31 130 years 1846 1865 1869 1869 1871 1873 1881 1886 1888 Invention and Innovation -

Camp Cooking Tips and Techniques

CAMP COOKING TIPS & TECHNIQUES A collection of information from the internet, from fellow Scouters and originated specifically for this booklet. Wood Badge Ticket Item – Karl Kuegler, Jr. Originally Created January 2008 - Revised & Expanded March 2017 Camp Cooking Tips & Techniques Page 1 Notes: ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ -

![Heating Systems [With Hand-Crafted Wood Stoves]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5781/heating-systems-with-hand-crafted-wood-stoves-605781.webp)

Heating Systems [With Hand-Crafted Wood Stoves]

Heating Systems [with hand-crafted wood stoves] Kompakt-Kessel B4 Tiles: Sommerhuber made in germany. 1 made in germany. BRUNNER was one of the first manufacturers to offer their hand-crafted wood-fired inserts as water heating capable devices. In addition to the usual tiled stove or fireplace effect in the room of installation, part of the available heat is supplied into the heating system. BRUNNERs decades of experience evolved into the most diverse applications of such constructions. Our partner craftsmen got acquainted with the design and limits of applications during numerous training sessions. This means safety for our valued customers, who want to secure their fundamental need for heat and warmth. All water heating inserts are approved for use as individual fire- places and comply with the requirements of the amended 1st Federal Immission Control Regulation (1.BImSchV). 2 Contents Page made in germany. 2 Next winter will come. 4 Independence day 9 Waterbearing tiled stoves. 10 Waterbearing fireplaces. 24 Waterbearing kitchen stoves. 34 Planning. 40 BRUNNER Heating Center. 44 The variants. 46 Kompakt-Kessel B4 - Tiles: Sommerhuber HKD 2.2 r with Kesselmodul - Tiles: Kaufmann Kompakt-Kessel B4 - Tiles: MEZ 3 Next winter will come. There is probably no more beautiful and reasonable way of securing heat for you home, than with a tiled stove or fireplace. As support for your existing heating system or in-between seasons - it is always good to provide heat with your domestic energy resources. This is related to a feeling of security and certainty, which derives from the ability to take care for the fundamental needs of your family. -

Residences for Rent – Week of February 20, 2017

Residences for Rent – Week of February 20, 2017 Bell Terrace Apartments 2701 SW 23rd St, Des Moines, IA 50321 (844) 324-8479 1 Bed $595 Application Fee: $40 A/C Wired for Cable Kitchen Oven Stove Refrigerator Drake Park Apartments 1260 34th St, Des Moines, IA 50311 (515) 635-3503 1 Bed $645 Application Fee: $40 High Speed Internet A/C Heating Ceiling Fans Smoke Free Wired for Cable Bathtub/Shower Microwave Stove Dishwasher Dine-In Kitchen Carpeting Vinyl Flooring Dining Area Walk-In Closets Window Coverings One time parking tag fee of $25. Garages available for $45 monthly rent. Cats Allowed $175 Deposit $25 Monthly Pet Rent $175 Fee 1 Pet Limit $350 deposit (175 refundable) with $25 monthly pet rent. Pet deposit is $350.00. Monthly pet rent of $25.00. National Biscuit Company Flats 1001 Cherry St, Des Moines, IA 50309 (515) 444-2454 Application Fee: $20 Income Restrictions Income restrictions apply to some or all residents. Contact the community for more information. Studio $465 High Speed Internet A/C Heating Smoke Free Wired for Cable Storage Units Wheelchair Accessible Granite Counters Microwave Refrigerator Wood Flooring Loft-Style Apartment Window Coverings Recurring Expenses Storage Fee: $25 Unassigned Surface Lot Parking: $20 Park Ridge 3200 Indianola Ave, Des Moines, IA 50315 Application Fee: $40 $250 Deposit 2 Beds $675 - $735 High Speed Internet A/C Heating Ceiling Fans Wired for Cable, Bathtub/Shower Dishwasher Dine-In Kitchen Stove Carpeting Vinyl Flooring Dining Area, Walk-In Closets Window Coverings Cats Allowed $20 Monthly Pet Rent $200 Fee 20 lb Weight Limit Cats must be spayed/neutered and front declawed. -

Picnic Pavilion/Scoutcraft Lodge

Picnic Pavilion/Scoutcraft Lodge Facility Type: Picnic Area Capacity: 100 or so Location: Near WU3 - Access via Main Parking Lot Scout Member Rate per Weekend: $25 +$1/per person/weekend Non-Member Rate per Weekend: $40 +$1/per person/weekend Facility Attributes Running Water Vehicle Access Kitchen Stove Electricity Gas Heat Kitchen Oven Cots & Mattresses Wood-Burning Stove Refrigerator Shower Fireplace Restroom Type: Latrine Note: All facilities are completely closed to visitors during the first and second weekend of hunting season. Typically, this season spans the end of November through the beginning of December. If you are interested in visiting Tuscarora at this time period, please call the Camping Secretary to ensure that the weekend when you would like to come is not during hunting season. The Picnic Pavilion is a 1,280 square foot enclosed, well lit, picnic area. There are sliding doors on all four sides to open it up on nice days, or you can close it down, fire up the wood furnace and make it a lil more cozy on those not-so-nice days. To the rear is an outdoor (covered) fire pit area which is great for cooking tin-foil meals, conducting a campfire ceremony in the pouring rain (the doors open to show the fire), or just to relax by. There is a water spigot outside that has seasonal water (15 Apr - 15 Oct). Nearby is a latrine (divided for male/female), complete with running water. There is space abound to set-up tents, play games, or conduct other types of program. We reccently added a propane fueled range for indoor cooking and for arts & crafts too! You must supply your own propane. -

Dual Basket Profry™

Consumer Service Information If you have any questions regarding the operation of your Presto appliance or need parts for your appliance, contact us by any of these methods: • Call 1-800-877-0441 weekdays 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM (Central Time) stainless steel • Email us through our website at www.GoPresto.com/contact • Write: National Presto Industries, Inc. Dual Basket ProFry Consumer Service Department 3925 North Hastings Way, Eau Claire, WI 54703-3703 immersion element deep fryer Inquiries will be answered promptly by telephone, email, or letter. When emailing or writ- ing, please include a phone number and a time when you can be reached during weekdays if possible. When contacting the Consumer Service Department, please indicate the model • Professional-style fryer with dual baskets. Fries two foods at once or and series numbers for the deep fryer. These numbers can be found on the back of the control extra-large batches. panel. Please record this information: • 1800-watt immersion element provides quick preheating and fast oil Model ___________________ Series _________ Date Purchased _________ temperature recovery. The Presto Factory Service Department is equipped to service all Presto appliances and sup- • Big 12-cup food capacity. ply genuine Presto parts. Genuine Presto replacement parts are manufactured to the same exacting quality standards as Presto appliances and are engineered specifically to function properly with its appliances. Presto can only guarantee the quality and performance of genuine Presto parts. “Look-alikes” might not be of the same quality or function in the same manner. To ensure that you are buying genuine Presto replacement parts, look for the Presto trademark. -

101 Recipes for the Deep Fryer Deep Fryer Italian Zeppole

101 Recipes For The Deep Fryer Deep Fryer Italian Zeppole 2-1/2 cups all purpose flour 1/8 tsp. salt 2-1/2 cups water 1/2 cup white wine olive oil 1 Tbs. ground cinnamon 1 cup sugar Sift flour and salt together in a bowl and set aside. Combine water and wine in a saucepan over medium high heat. Do not boil. When bubbles appear on the bottom of the pan, add flour mixture all at once. Stir constantly with a wooden spoon until dough comes together into a ball. Transfer to a lightly oiled work surface. Pound with a rolling pin about 10 minutes, until smooth. Roll dough into strips about 1/2 inch around. Cut into 8 inch lengths and pinch ends together to make rings. Heat oil in an electric deep fryer to 375°F. Without overcrowding, deep fry 2-3 pieces at a time 3-4 minutes until golden, pricking each one with a skewer as it fries. Drain on absorbent paper. Combine cinnamon and sugar in a bowl. Dip zeppole in sugar mixture while still hot. Deep Fryer Sopaipillas vegetable oil 1 cup all purpose flour 1/2 tsp. salt 1/2 tsp. baking powder 1-1/2 tsp. nonfat dry milk 1 tsp. vegetable shortening 1/2 cup cold water Heat oil in an electric deep fryer to 370°F - 380°F. Combine flour and next 4 ingredients in a food processor and pulse 3-4 times. With machine running, pour in water through feed tube and process about 15 seconds, or until ingredients begin to come together. -

Section B: KITCHEN APPLIANCES

Form EIA-457A (1997) Form Approval: OMB No.: 1905-0092 Household Questionnaire Expires: March 31, 2000 U.S. Department of Energy Energy Information Administration 1997 Residential Energy Consumption Survey Household Questionnaire Section B: KITCHEN APPLIANCES B-1 STOVEN Now I have some questions about your use of kitchen appliances. Please look at Exhibit B-1. Do you have a kitchen stove that has both burners and an oven? Yes .................... 1 No ..................... 0 [If Yes] ELSTOVE NGSTOVE LPSTOVE OTHSTOVE What type of fuel does that stove use? Is it . Electricity, ........................... 05 Natural gas from underground pipes, ..... 01 Bottled gas (LPG or Propane), or ........ 02 Some other fuel? ..................... 21 Don't know ........................... 96 [If No] STOVE Do you have a separate built-in range top or burners? Yes .................... 1 No ..................... 0 [If Yes] ELSTOVE NGSTOVE LPSTOVE OTHSTOVE What type of fuel does that stove use? Is it . Electricity, ........................... 05 Natural gas from underground pipes, ..... 01 Bottled gas (LPG or Propane), or ........ 02 Some other fuel? ..................... 21 Don't know ........................... 96 [If No] OVEN Do you have a separate built-in oven? Yes ................... 1 No ..................... 0 [If Yes] ELOVEN NGOVEN LPOVEN OTHOVEN What type of fuel does that oven use? Is it . Electricity, ........................... 05 Natural gas from underground pipes, ..... 01 Bottled gas (LPG or Propane), or ........ 02 Some other fuel? ..................... 21 Don't know ........................... 96 1 Form EIA-457A (1997) Form Approval: OMB No.: 1905-0092 Household Questionnaire Expires: March 31, 2000 B-2 [If STOVEN=Yes or OVEN=Yes] OVENUSE Please look at Exhibit B-2. Which of the categories shown best describes, on average, how often you use your oven? More than once a day .................. -

Global Growth Trends in Small Appliance Markets Udo Jansen Global Director Small Domestic Appliances

Global Growth Trends in Small Appliance Markets Udo Jansen Global Director Small Domestic Appliances April 2018 IFA Global Press Conference © GfK April 19, 2018 | Global Growth Trends in Small Appliance Markets 1 In 2017, the global Small Appliances Market, based on NPD`s and GfK`s retail panels, reached 65.2 billion USD Small Appliances (all monitored product groups) – Global Panelmarket – 2017 . Hot beverage makers . Electric water kettles . Food preparation . Rice cookers . Toasters 65.2 . Juicers . Fun cooking . Mini ovens billion USD . Deep fryers . Barbecues . Shavers . Hair dryers . Hair stylers . Irons . Vacuum cleaners +8% . Steam Cleaner . Air treatment vs. 2016 . Electrical fans (constant currency) . Electrical heating … … and more Source: GfK- and NPD Point-of-Sale Tracking © GfK April 19, 2018 | Global Growth Trends in Small Appliance Markets 2 Innovation © GfK April 19, 2018 | Global Growth Trends in Small Appliance Markets 3 Global SDA market1 is driven by innovations and smart appliances. New products make the everyday life of consumers easier. SDA total | World Panelmarket | Sales billion € 11 32 37 Hot water dispenser 96 103 44 Personal scales with Mobile Connect. 7.1 billion 128 185 51 Foodpreparation with shredder 296 Massage mat 336 68 Espresso Full. with Mobile Connect 1.882 mn 415 Trad. filtercoffee with int. coffee grinder 477 Hybrid Groomer Window cleaner 510 Waterjet solo (Dental Care) Toothbrush Rech. with Mobile Connect. 27,7 billion 38,4 billion Slow juicers 1364 Laser/IPL hair removal Electrical cooking pots Foodpreparation with cooking function 2926 Hot Air Fryers Robot vacuum cleaners 2012 2017 Handstick rechargeable vac cleaners 1 Without U.S. -

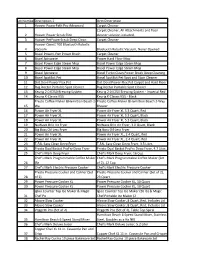

Lot Numberdescription 1 Item Description 1 Hoover Powerpath

Lot NumberDescription 1 Item Description 1 Hoover PowerPath Pro Advanced Carpet Cleaner Carpet Cleaner, All Attachments and floor 2 Hoover Power Scrub Elite cleaner solution included, 3 Hoover PetPowerScrub Deep Clean Carpet Cleaner Hoover Qwest 700 Bluetooth Robotic 4 Vacuum Bluetooth Robotic Vacuum, Never Opened 5 Bissel PowerLifter Power Brush Carpet Cleaner 6 Bissel Spinwave Power Hard Floor Mop 7 Bissel Power Edge Steam Mop Bissel Power Edge Steam Mop 8 Bissel Power Edge Steam Mop Bissel Power Edge Steam Mop 9 Bissel Spinwave Bissel Turbo Clean Power Brush Deep Cleaning 10 Bissel SpotBot Pet Bissel SpotBot Pet Spot and Stain Cleaner 11 Dirt Devil Power Flex Pet Dirt Devil Power Flex Pet Carpet and Hard Floor 12 Rug Doctor Portable Spot Cleaner Rug Doctor Portable Spot Cleaner 13 Keurig 2.0 K250 Brewing System Keurig 2.0 K250 Brewing System - Imperial Red 14 Keurig K-Classic K55 Keurig K-Classic K55 - Black Presto Coffee Maker &Hamiltion Beach 2- Presto Coffee Maker &Hamiltion Beach 2-Way 15 Wa Brewer 16 Power Air Fryer XL Power Air Fryer XL 5.3 Quart, Red 17 Power Air Fryer XL Power Air Fryer XL 5.3 Quart, Black 18 Power Air Fryer XL Power Air Fryer XL 5.3 Quart, Black 19 NuWave Brio Air Fryer NuWave Brio Air Fryer, 3.0 Quart, Black 20 Big Boss Oil-Less Fryer Big Boss Oil-Less Fryer 21 Power Air Fryer XL Power Air Fryer XL, 2.4 Quart, Red 22 Power Air Fryer XL Power Air Fryer XL, 2.4 Quart, Red 23 T-FAL Easy Clean Deep Fryer T-FAL Easy Clean Deep Fryer, 3.5 Liter, 24 Presto Dual Basket ProFry Deep Fryer Presto Dual Basket ProFry Deep -

Vacating Guide

VACATING PROCEDURES Submit a “Intent to Vacate Notice” Pre-vacate checks will be done prior to check out by Apartment Manager Make a check out appointment with your Apartment Manager – at least one week prior to your vacate date. Failure to keep or make an appointment may result in a $25.00 IMPROPER CHECKOUT CHARGE Be sure your rent is paid in full File a forwarding address with the US Post Office -can be done on-line at www.USPS.gov Discontinue all deliveries to the apartment prior to departure Clean apartment to University standard using the following guide Turn all keys into your Apartment Manager at your check out appointment BEFORE YOU LEAVE…. The University is anxious to assist you in leaving your apartment in good condition so a new resident may move in directly after you vacate. We would also like to help you minimize damage and cleaning charges to your account. Our charges reflect actual costs and are strictly applied. Your inventory sheet is used to determine if there will be charges. As a general rule, the apartment should be left in the same condition in which you would like to move into. HINT: WE SUGGEST THAT YOU START CLEANING EARLY, DOING A LITTLE HERE AND THERE, INSTEAD OF TRYING TO DO IT ALL AT THE LAST MINUTE Questions about cleaning, vacating procedures, inspection, and damage charges should be directed to the Apartment Managers Please contact the West Emergency Duty Phone Campus Community Center at 231-250-7769 231-591-3781 or your Apartment Manager. West Campus Community Center 231-591-3781 Update 9/17/2012