The Providence Journal Art: Old R.I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Matter of Truth

A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle for African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) Cover images: African Mariner, oil on canvass. courtesy of Christian McBurney Collection. American Indian (Ninigret), portrait, oil on canvas by Charles Osgood, 1837-1838, courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society Title page images: Thomas Howland by John Blanchard. 1895, courtesy of Rhode Island Historical Society Christiana Carteaux Bannister, painted by her husband, Edward Mitchell Bannister. From the Rhode Island School of Design collection. © 2021 Rhode Island Black Heritage Society & 1696 Heritage Group Designed by 1696 Heritage Group For information about Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, please write to: Rhode Island Black Heritage Society PO Box 4238, Middletown, RI 02842 RIBlackHeritage.org Printed in the United States of America. A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle For African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) The examination and documentation of the role of the City of Providence and State of Rhode Island in supporting a “Separate and Unequal” existence for African heritage, Indigenous, and people of color. This work was developed with the Mayor’s African American Ambassador Group, which meets weekly and serves as a direct line of communication between the community and the Administration. What originally began with faith leaders as a means to ensure equitable access to COVID-19-related care and resources has since expanded, establishing subcommittees focused on recommending strategies to increase equity citywide. By the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society and 1696 Heritage Group Research and writing - Keith W. Stokes and Theresa Guzmán Stokes Editor - W. -

H 5530 State of Rhode Island

2019 -- H 5530 ======== LC001963 ======== STATE OF RHODE ISLAND IN GENERAL ASSEMBLY JANUARY SESSION, A.D. 2019 ____________ H O U S E R E S O L U T I O N EXTENDING CONGRATULATIONS Introduced By: Representatives Shekarchi, and Filippi Date Introduced: February 26, 2019 Referred To: House read and passed 1 WHEREAS, It has been made known to the House that certain persons and organizations 2 are deserving of commendation; and 3 Mabel Arsenault; the joyous and momentous occasion of your 100th Birthday on February 4 21, 2019; 5 Representative Donovan 6 Savanah Joy Ziobrowski, Justyce Scott, Aaron J. Stanley, Anthony J. Stroker, Bastian 7 Vallo Acheé, Benjamin O'Brien, Dominic Andrew Burke, Drake Scott Dumont, Gabriel Antonio- 8 Francisco Abreu, Logan Parker Proulx, Robert Antonnio Namias, Zackery West Snowman, Cub 9 Scouts Pack 13; the prestigious honor of receiving the "Arrow of Light Award" for your 10 commitment and dedication to preparing yourself for crossing over from the Cub Scouts to the 11 Boy Scouts and embarking on a new adventure in scouting; 12 Representatives Noret, Jackson and Serpa 13 Cindy Medeiros; your retirement after 21 years of dedicated and faithful service to the 14 people of the city of Pawtucket, as a member of the Pawtucket Parks and Recreation Department; 15 Representative Tobon 16 Rachel Roberge, teacher, Scituate High School; the distinguished honor of receiving the 17 "Golden Apple Award" sponsored by the RI Department of Education and NBC 10 WJAR for 18 demonstrating the true spirit of teaching by making classrooms -

State of Rhode Island

2006 -- H 7919 ======= LC02840 ======= STATE OF RHODE ISLAND IN GENERAL ASSEMBLY JANUARY SESSION, A.D. 2006 ____________ H O U S E R E S O L U T I O N EXTENDING CONGRATULATIONS Introduced By: Representatives Fox, and Watson Date Introduced: March 21, 2006 Referred To: House read and passed 1 WHEREAS, It has been made known to the House that certain persons and organizations 2 are deserving of commendation; and 3 Willard and Virginia Caron; the joyous and momentous celebration of your 50th 4 Wedding Anniversary on September 28, 2005; 5 Representative Winfield 6 Lt. Edward J. Lee, Detective Sgt. Steven Nowak and BCI Detective Gerard Durand, 7 Woonsocket Police Department; your commitment and dedication to protect the citizens of the 8 City of Woonsocket and your untiring efforts in the arrest and prosecution of Serial Killer Jeffery 9 Mailhot; 10 Representative Brien 11 Robert J. Palazzo, CAA; being honored as the 2006 St. Joseph's Day Merit Award 12 recipient; 13 Representative Smith 14 The Valley Breeze; the 10th Anniversary celebration on March 23, 2006 of "The Valley 15 Breeze" providing the citizens of the Blackstone Valley with news and information that affects 16 their daily lives; 17 Representative Singleton 18 Andrew D. Oliver and Eric C. DiBiasio, Troop 20, Johnston; attaining the rank of Eagle 19 Scout in the Boy Scouts of America and the distinction you bring to yourself, family and your 20 community; 1 Representative Ucci 2 Timothy Francis Fitzgerald; the joyous and momentous celebration of your 80th Birthday 3 on March 21, 2006; 4 Representatives Crowley and Shanley 5 Joseph Alphonse St. -

Rhode Island Department of State Teacher Resources - Secretary of State Nellie M

Rhode Island Department of State Teacher Resources - Secretary of State Nellie M. Gorbea 1 I. COVER PAGE Rhode Island Secretary of State Nellie M. Gorbea Project Leads: Lane Talbot Sparkman, Associate Director of Education & Public Programs Phone: 401-330-3182 Email: [email protected] Kaitlynne Ward, Director of State Archives, Library & Public Information Phone: 401-329-0120 Email: [email protected] Project Title: Rhode Island Department of State Educator Resources Project Description: A Department-wide focus on creating tools and programs for educators seeking to teach Rhode Island history and civics, and the creation of a staff position to serve as their designated point of contact. General Subject Area: State Heritage. Rhode Island Department of State Teacher Resources - Secretary of State Nellie M. Gorbea 2 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY HISTORY Declining Civic Participation Upon entering office in 2015, Secretary of State Nellie M. Gorbea made • Only 23% of 8th graders increasing civic engagement, especially among young people, a pri- demonstrated proficiency in civics ority of her administration. Secretary Gorbea understood the need for on the 2014 National Assessment of increased civic education and knowledge of Rhode Island history to Educational Progress.1 bolster civic pride and participation throughout the state. To accomplish • According to a survey by the this, she realigned existing responsibilities within the Department of Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship State (Department) to create a new full-time equivalent (FTE) position, Association, only 36% of American Associate Director of Education and Public Programs. This position is adults would pass the US citizenship responsible for collaborating with the Elections, State Library, and State test taken by immigrants working to Archives Divisions to manage existing programs related to Rhode Island attain citizenship.2 history and civic education and identifying opportunities to develop new • A class-action lawsuit was recently programs and teaching materials. -

2018 Holiday Concerts Flyer

2018 Holiday Concerts at the Rhode Island State House • Wednesday, December 12 at 10:30 AM, Roger Williams Middle School Chorus • Tuesday, November 27 at 9:30 AM, Lillian Feinstein Elementary Grade 4/5 from Roger Williams Middle School in Providence Guitar Ensemble from Lillian Feinstein Elementary in Providence • Wednesday, December 12 at 11:30 AM, Hampden Meadows School 4th Grade • Tuesday, November 27 at 10:30 AM, Cedar Hill Elementary School Chorus from Chorus from Hampden Meadows School in Barrington Cedar Hill Elementary School in Warwick • Thursday, December 13 at 9:30 AM, John F Deering Middle School Mixed • Wednesday, November 28 at 9:30 AM, Hope Highlands Middle School Concert Ensembles from John F Deering Middle School in West Warwick Band / Chorus / Orchestra from Hope Highlands Middle School in Cranston • Thursday, December 13 at 10:30 AM, Cole Middle School Music from Cole • Wednesday, November 28 at 10:30 AM, Bishop McVinney School Choir from Middle School in East Greenwich Bishop McVinney School in Providence • Thursday, December 13 at 11:30 AM, Saint Philip School Chorus from Saint • Wednesday, November 28 at 11:30 AM, Combined Voices of Whiteknact and Philip School in Greenville Orlo Elementary Schools from Whiteknact Elementary and Orlo Avenue Elemen- • Thursday, December 13 at 12:00 PM, Westerly High School Chorus from West- tary in East Providence erly High School in Westerly • Thursday, November 29 at 9:30 AM, Hope Elementary School Chorus from • Friday, December 14 at 9:00 AM, Nayatt Elementary Grade 3 Chorus from -

The Rhode Island State House

THE RHODE ISLAND STATE HOUSE: The Competition (1890-1892) by Hilary A. Lewis Bachelor of Arts Princeton University Princeton, New Jersey 1984 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY FEBRUARY 1988 (c) Hilary A. Lewis 1988 The Author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. .Signature of author Hilary A. Lewis artment of Architecture January 15, 1988 Certified by Sta ford Anderson Professor of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Accepted by 'Julian Beinart Chairman Departmental Committee for Graduate Students OF E-THNOLOGY UBMan Rot' CONTENTS A. Contents......... .............................. .1 B. Acknowledgements. ............. ................. .2 C. Abstract......... ...............................3 I. Introduction....................................4 II. Body of the Text: The Beginnings of the Commission.... ........... 8 The Selection of McKim, Mead & White .......... 23 Following the Competition........... .......... 39 III. Conclusion.....................................44 IV. Appendices "A" The Conditions for the Competition. ....... 47 "B" Statements of the Governors........ ....... 57 Letters................................. ....... 79 McKim and Burnham...................... ...... 102 The City Plan Commission Report........ 105 Illustrations of Competing Designs..... ...... 110 V. Bibliography............................ ...... 117 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis was written under the direction of Professor Neil Levine, Chairman of the Fine Arts Department at Harvard University. Professor Levine has not only been extremely helpful with this project; he has been a wonderful teacher who has a gift for instilling his love of the subject in others. I thank him for all of his guidance. H.A.L. Cambridge 2 THE RHODE ISLAND STATE HOUSE: The Competition (1890-1892) by Hilary A. -

Researching the Laws of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations: from Lively Experiment to Statehood Gail I

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU Law Library Staff ubP lications Law Library 2005 Researching the Laws of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations: From Lively Experiment to Statehood Gail I. Winson Roger Williams University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.rwu.edu/law_lib_sp Part of the Legal History Commons, and the Legal Writing and Research Commons Recommended Citation Winson, Gail I., "Researching the Laws of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations: From Lively Experiment to Statehood" (2005). Law Library Staff Publications. 3. https://docs.rwu.edu/law_lib_sp/3 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Library at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Researching the Laws of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations: From Lively Experiment1 to Statehood by Gail I. Winson* I. Introduction Roger Williams is generally recognized as the founder of Rhode Island. Although his settlement of Providence in 1636 was not the first or only settlement in the area, he was able to open the whole region to English settlement.2 Due to his friendship with local Indians and knowledge of their language he obtained land from the Indians and assisted other settlers in doing the same. When Williams was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1635 because of his rejection of Puritanism, his friend, Governor John Winthrop, suggested that he start a new settlement at Narragansett Bay.3 Founders of other early settlements also migrated from the Massachusetts colony seeking religious freedom. -

MJB-RESUME.Pdf

M A R Y J A N E B E G I N 401-247-7978 www.maryjanebegin.com [email protected] SUMMARY: • Rhode Island based award-winning children’s book illustrator and author. • 22 years teaching experience at Rhode Island School of Design, with expertise in teaching a broad range of conceptual, technical and professional courses. • 21 years experience providing presentations and lectures to schools and public organizations. • 26 years experience as freelance illustrator in a variety of Illustration industries: traditional publishing, educational publishing, character development for animation, advertising, licensing, and original art sales and exhibition. EDUCATION: RHODE ISLAND SCHOOL OF DESIGN 1981-1985 Providence, Rhode Island Bachelor of Fine Arts in Illustration- Honors BROWN UNIVERSITY 2009 Providence, RI Sheridan Teaching Certificate I PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT: Hasbro- Three-day workshop on Resin casting and Z-Brush 3D sculpting 2010 Harriet W. Sheridan Center Teaching Certificate Program at Brown University 2009 RISD Figure Sculpting Course-Summer Studies 2008 PTFA Grant Funded tutorials on Adobe digital programs 2008 SURTEX- Surface and Textile Licensing Show- lectures and workshops 2003-2007 ICON-Illustrators Conference - lectures and workshops 1999, 2003, 2004 ALA-American Library Association- lectures and workshops 2004 1 of 11 WORK HISTORY: RHODE ISLAND SCHOOL OF DESIGN Providence, Rhode Island Faculty- Adjunct, Senior Critic 1991-present Faculty- Full-Time, Assistant Professor-Term Position 1998-2000, 2009-2010 COURSES: What’s Your Story, -

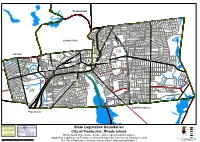

New House and Senate Lines for Pawtucket

Cumberland Blackstone Riv Crest Dr t Barney Pond Weldon S St H in u Colv D St Scott Pond lton R d Ke ill St e M m s e o v i e C J n n u r g e e e Av t S yon d Ken r S a a t St S Valley Falls Pond S er s t rch r A t n b G S E o r t R a o t l r S w C e S m el o he i r W c t o r k c S a i r e u t e n t y t S R t chem n s W S a S l S t M n S d i e t lv D t Co y o Bellmore Dr y t a r o S L p O S G d l o t St b e t e r v a o n C m ll St u c r de g en r r d t W lint S s e t F y S f K s J n e n icke s D u S S i l e t r l Rose Dr l k o t r i t D a t D w S D S son r n Daw e St i R t m oos o a evelt t H r Ave S S C n r S t e a t l Riley St g e D e a t t D t w t o o E S r s Mc C r Ca T be Ave St s Dr t et B ole e t Ave S n Fle P i wry s o r n M S l o a e r a g art D c Collins w l B t B A St c ve ster e e Fo M t m l y k Don Ct I o n i n A b d S St o rn P bu u u t Cushman St Wash d t Columbine Ave t Stearns St r t t s t g n t S t t S t L S S o d S l r S u r o D G d i n a S a S l a S o Ar e Clark A d ve r n A n l D l r n n a Ch d l arpe t Ca t n y tie H n r o i A o o ve t a e g i a r t l S w S s a c s d n C y o i Pe A ckh r am n y S t n t b s a d A l a m P u 1 o e a t Flora S. -

Rhode Island State History Lapbook Journal

LJ_SRI Rhode Island State History Lapbook Journal Designed for 6th-12th Grades, but could be adjusted for younger grade levels. Written & designed by Cyndi Kinney & Judy Trout of Knowledge Box Central Rhode Island History Lapbook Journal Copyright © 2012 Knowledge Box Central www.KnowledgeBoxCentral.com ISBN # Ebook: 978-1-61625-731-6 CD: 978-1-61625-732-3 Printed: 978-1-61625-734-7 Publisher: Knowledge Box Central http://www.knowledgeboxcentral.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided by USA copyright law. The purchaser of the eBook or CD is licensed to copy this information for use with their immediate family members only. If you are interested in copying for a larger group, please contact the publisher. Printed format is not to be copied and is consumable. It is designed for one student only. All information and graphics within this product are originals or have been used with permission from its owners, and credit has been given when appropriate. These include, but are not limited to the following: www.iclipart.com, and Art Explosion Clipart. Rhode Island State History Lapbook Journal Thanks for purchasing this product. Please check out our Lapbook Journals for other states. The Lapbook Journals are designed for 6th-12th grades but could be adjusted for use with younger students. Please also check out our Lapbooks for each state. The Lapbooks are designed for K-8th grades. -

Capital Steps Passport

Started Trip On: ___________________ Completed Trip On: ________________ This passport belongs to: ____________________________________________________________________________________ Photos and facts from: https://www.cntraveler.com/galleries/2013-07-05/photos-celebrate-nation-50-state- capitol-buildings Maine State House, Augusta, ME 04330 Year completed**: 1832 Architectural style: Greek Revival FYI: The portico and front and rear walls are all that remain of the original, 1832 structure (designed by architect Charles Bullfinch). A major remodel in 1909–1910 enlarged the wings of the building and replaced the building’s original dome with a more elongated one. New Hampshire State House, 107 North Main Street, Concord, NH 03303 Year completed**: 1819 Architectural style: Greek Revival FYI: The stately eagle installed on top of the New Hampshire State House’s dome may look gold, but it’s actually brass. The original was removed for preservation and is on display at the New Hampshire Historical Society. A new, gold-leafed eagle was put in its place around 1969. Vermont State House, 115 State Street, Montpelier, VT 05633 Year completed**: 1859 Architectural style: Renaissance Revival FYI: The senate chamber still has its original furnishings, plus working gas lamps, and a “gasolier”—a gaslight chandelier that was rediscovered elsewhere in 1979, refurbished, and reinstalled in the chamber. New York State Capitol, State St. and Washington Ave, Albany, NY 12224 Year completed**: 1899 Architectural style: Italian Renaissance/French Renaissance/Romanesque FYI: The Western staircase inside New York’s capitol has been dubbed the “Million Dollar Staircase,” because it cost more than a million dollars to build—in the late-1800s, no less. -

Rhode Island Government & History

A GUIDE TO RHODE ISLAND GOVERNMENT & HISTORY Nellie M. Gorbea Secretary of State OUR STATE What city or town do you live in? ___________________________ Can you identify each city and town on the map? Barrington Exeter New Shoreham (Block Island) Smithfield Bristol Foster Newport South Kingstown Burrillville Glocester North Kingstown Tiverton Central Falls Hopkinton North Providence Warren Charlestown Jamestown North Smithfield Warwick Coventry Johnston Pawtucket West Greenwich Cranston Lincoln Portsmouth West Warwick Cumberland Little Compton Providence Westerly East Greenwich Middletown Richmond Woonsocket East Providence Narragansett Scituate Rhode Island Department of State As Secretary of State, I want all Rhode Islanders to know about our amazing state and to understand how our Rhode Island State House government works. This book has information about Rhode 82 Smith Street Island, our State House, and our government. I know you Providence, RI 02903 will enjoy learning about our state’s rich history and its important contributions to the growth and prosperity of the United States of America. [email protected] I encourage you to visit our magnificent State House where www.sos.ri.gov you can see the treasures described in this book, and learn even more about how our state government works. Visit (401) 222-3983 the rooms where laws are made and learn more about how you can have a voice in decisions that affect you. We Follow us on Twitter offer free guided tours every weekday, except holidays. @RISecState To schedule a tour call us at (401) 222-3983 or email us at Like us on Facebook [email protected].