The Calderdale Way at Heptonstall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

826 INDEX 1066 Country Walk 195 AA La Ronde

© Lonely Planet Publications 826 Index 1066 Country Walk 195 animals 85-7, see also birds, individual Cecil Higgins Art Gallery 266 ABBREVIATIONS animals Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum A ACT Australian Capital books 86 256 A La RondeTerritory 378 internet resources 85 City Museum & Art Gallery 332 abbeys,NSW see New churches South & cathedrals Wales aquariums Dali Universe 127 Abbotsbury,NT Northern 311 Territory Aquarium of the Lakes 709 FACT 680 accommodationQld Queensland 787-90, 791, see Blue Planet Aquarium 674 Ferens Art Gallery 616 alsoSA individualSouth locations Australia Blue Reef Aquarium (Newquay) Graves Gallery 590 activitiesTas 790-2,Tasmania see also individual 401 Guildhall Art Gallery 123 activitiesVic Victoria Blue Reef Aquarium (Portsmouth) Hayward Gallery 127 AintreeWA FestivalWestern 683 Australia INDEX 286 Hereford Museum & Art Gallery 563 air travel Brighton Sea Life Centre 207 Hove Museum & Art Gallery 207 airlines 804 Deep, The 615 Ikon Gallery 534 airports 803-4 London Aquarium 127 Institute of Contemporary Art 118 tickets 804 National Marine Aquarium 384 Keswick Museum & Art Gallery 726 to/from England 803-5 National Sea Life Centre 534 Kettle’s Yard 433 within England 806 Oceanarium 299 Lady Lever Art Gallery 689 Albert Dock 680-1 Sea Life Centre & Marine Laing Art Gallery 749 Aldeburgh 453-5 Sanctuary 638 Leeds Art Gallery 594-5 Alfred the Great 37 archaeological sites, see also Roman Lowry 660 statues 239, 279 sites Manchester Art Gallery 658 All Souls College 228-9 Avebury 326-9, 327, 9 Mercer Art Gallery -

Heptonstall Newsletter Nov 2012 Colour

Age uk Age UK Calderdale & Kirklees Health and Commu- nity Services team are working with ‘Good Heptonstall Neighbour Scheme’. They aim to alleviate a lot of the problems associated with later life. Newsletter A project which the people of Heptonstall are likely Nov 2012 to hear a lot more about is ‘LOCAL LINK’. A newsletter covering Local Link is managed by Andrew Fearnley, who has events and issues for a network of Community Volunteers, mainly in rural areas of Calderdale, who act as ‘eyes and ears’ of everyone living within the their local communities, to support isolated older Civil Parish of Heptonstall people. Mary Cockcroft and Jean Leach are our vol- unteers in the Heptonstall area. Andrew also runs a scheme called ‘SAFE & WARM’, offering Home Energy Information and Advice, with support in applying for grants and reducing fuel poverty amongst vulnerable older people. The ‘ACTIVE BEFRIENDING PROJECT’, co- ordinated by Christine Henry offers ‘one to one’ sup- port for isolated people throughout Calderdale. Trained volunteers are linked with lonely older peo- ple who feel depressed and socially isolated. The scheme is focused on engaging people in activities with their befriender, in order to restore confidence and gain more out of life. People are referred to the scheme through various channels; usually by Health Professionals, but often by family or neighbours and sometimes by the per- son who actually needs the support. Andrew and Christine can be contacted at Age UKCK Choices Centre, Woolshops, Halifax. For fur- ther information Tel 01422 399830. Contents include Parish Council News Newsletters for the housebound Church News Do you know someone in the village who is housebound? Church Bells Refurbishment School Big Night Out If you do, please let us know and we’ll make sure that a copy of the Newsletter is delivered to them. -

Wakefield, West Riding: the Economy of a Yorkshire Manor

WAKEFIELD, WEST RIDING: THE ECONOMY OF A YORKSHIRE MANOR By BRUCE A. PAVEY Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1991 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1993 OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY WAKEFIELD, WEST RIDING: THE ECONOMY OF A YORKSHIRE MANOR Thesis Approved: ~ ThesiSAd er £~ A J?t~ -Dean of the Graduate College ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply indebted to to the faculty and staff of the Department of History, and especially the members of my advisory committee for the generous sharing of their time and knowledge during my stay at O.S.U. I must thank Dr. Alain Saint-Saens for his generous encouragement and advice concerning not only graduate work but the historian's profession in general; also Dr. Joseph Byrnes for so kindly serving on my committee at such short notice. To Dr. Ron Petrin I extend my heartfelt appreciation for his unflagging concern for my academic progress; our relationship has been especially rewarding on both an academic and personal level. In particular I would like to thank my friend and mentor, Dr. Paul Bischoff who has guided my explorations of the medieval world and its denizens. His dogged--and occasionally successful--efforts to develop my skills are directly responsible for whatever small progress I may have made as an historian. To my friends and fellow teaching assistants I extend warmest thanks for making the past two years so enjoyable. For the many hours of comradeship and mutual sympathy over the trials and tribulations of life as a teaching assistant I thank Wendy Gunderson, Sandy Unruh, Deidre Myers, Russ Overton, Peter Kraemer, and Kelly McDaniels. -

Scenic Bus Routes in West Y Rkshire

TICKETS Scenic Bus Routes For travel on buses only, ask the driver for a ‘MetroDay’ ticket. It costs £6 on the bus*. If you are in West Y rkshire travelling both on Saturday and Sunday, ask for a ‘Weekender’. It costs £8. They are valid on all buses at any time within West Yorkshire. *For travellers who need 3 or more day tickets on different days, you can save money by using an MCard smartcard - buy at Leeds Bus Station For travel on buses and trains, buy a ‘Train & Bus DayRover’ at Leeds Bus Station. It costs £8.20. If there are 2 of you, ask for a ‘Family DayRover’. This ticket includes up to 3 children. It costs £12.20. Mon - Fri these tickets are NOT valid on buses before 9.30 or trains before 9.30 and between 16.01 & 18.30 There is a Bus Map & Guide for different areas of West Yorkshire. The 4 maps that cover this tour are: Leeds, Wakefield, South Kirklees & Calderdale. They are available free at Leeds Bus Station. Every bus stop in the county has a timetable. Printed rail timetables for each line A Great Day Out are widely available. See page on left for online and social media Pennine Hills & Rishworth Moor sources of information Holme & Calder Valleys Wakefield & Huddersfield Please tell us what you think of this leaflet and how your trip went at [email protected] Have you tried Tour 1 to Haworth? All on the One Ticket! 110 to Kettlethorpe / Hall Green Every 10 minutes (20 mins on Leeds Rail Sundays). -

Yorkshire Journal Issue 3 Autumn 2014

TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall Issue 3 Autumn 2014 In this issue: One Summer Hornsea Mere Roman Signal Stations on the Yorkshire Coast The Curious Legend of Tom Bell and his Cave at Hardcastle Crags, Near Halifax Jervaulx Abbey This wooden chainsaw sculpture of a monk is by Andris Bergs. It was comissioned by the owners of Jervaulx Abbey to welcome visitors to the Abbey. Jervaulx was a Cistercian Abbey and the medieval monks wore habits, generally in a greyish-white, and sometimes brown and were referred to as the “White Monks” The sculptured monk is wearing a habit with the hood covering the head with a scapula. A scapula was a garment consisting of a long wide piece of woollen cloth worn over the shoulders with an opening for the head Some monks would also wear a cross on a chain around their necks Photo by Brian Wade The Yorkshire Journal Issue 3 Autumn 2014 Left: Kirkstall Abbey, Leeds in autumn, Photo by Brian Wade Cover: Hornsea Mere, Photo by Alison Hartley Editorial elcome to the autumn issue of The Yorkshire Journal. Before we W highlight the articles in this issue we would like to inform our readers that all our copies of Yorkshire Journal published by Smith Settle from 1993 to 2003 and then by Dalesman, up to winter issue 2004, have all been passed on to The Saltaire Bookshop, 1 Myrtle Place, Shipley, West Yorkshire BD18 4NB where they can be purchased. We no longer hold copies of these Journals. David Reynolds starts us off with the Yorkshire Television drama series ‘One Summer’ by Willy Russell. -

Hebden Bridge Local History Society 2008 Heptonstall Church Inscriptions

Hebden Bridge Local History Society 2008 Heptonstall Church inscriptions The work on transcribing the graves in the old graveyard around St. Thomas Church is ongoing. This is the work done so far. To the left of the new church north porch is this memorial Brother did not get inheritance from Father because the Father was accused of Felony by wife's father? The Bad Wife tomb. The Whole Story. MG - 1808 Aged 78 In memory of William Greenwood of Pecket Well who was found dead at Bridwell Head in Wadsworth on the 14th day of August 1820. He was forsaken by a bad wife who enforced him to serveth his Magesty in the 3rd Reg Militia for 8 years. He left a girl aged 16 years to be cozened (cheated) by her Mothers Father (Grandfather) out of his money. his own Father deposed (divest of office) for Felony (crime which incurs forfeiture of lands or goods). His own brother James Greenwood who was before a Magestrate for his Rament (Pament?) which he had bequested to him before his (death) in the presents of two (fathers?) witnesses. His bread of life now spent. His age near 35 years and in his trouble dropped down and left his vale of tears. James Greenwood Stone T G Location of this one? In memory of John Ashworth, of Hebden Bridge, who died July 2 1887,aged 72 years Also of Richard Fox Ashworth, his son, who died Feby 28th 1888 Aged 48 years Also of Hannah, relict of the above John Ashworth, who died April 8th 1894, Aged 78 years “Her end was peace.” B/Marshall/1 Mary Ann Marshall 1820? April? 8 years Also Abraham Marshall All who died Decr 25th 1839 Aged 52 years B/Marshall/2 W.H. -

Sample Pages

SAMPLESAMPLE PAGESPAGES The 80-page, A4 handbook for Yorkshire Mills & Mill Towns, with text, photographs, maps, appendices and a reading list, is available for purchase, price £15.00 including postage and packing. Please send a cheque, payable to Mike Higginbottom, to – 63 Vivian Road Sheffield S5 6WJ YorkshireYorkshire MillsMills && MillMill TownsTowns Great Victoria Hotel, Bridge Street, Bradford BD1 1JX 01274-728706 Thursday September 20th-Monday September 24th 2012 2 Contents Introduction .................................................................................... 7 Bradford ......................................................................................... 8 Nineteenth-century expansion .............................................................................. 10 Nineteenth-century trade .................................................................................... 10 Bradford’s South Asian communities ..................................................................... 14 Bradford tourism ............................................................................................... 17 Eccleshill & Undercliffe ...................................................................................... 20 Manningham Mills .......................................................................... 24 Saltaire ......................................................................................... 26 Heptonstall .................................................................................... 32 Hebden Bridge -

The English Ancestry of Richard' Belden of Wethersfield, Connecticut

THE ENGLISH ANCESTRY OF RICHARD' BELDEN OF WETHERSFIELD, CONNECTICUT With an Account of the Death in England of Richard Baildon, Son of Sir Francis Baildon of Kippax, Yorkshire By Paul C. Reed, FASG , and John C. B. Sharp Donald Lines Jacobus long ago criticized the proposed origin of the immigrant Richard' Belden, who first appeared in Wethersfield, Connecticut, in 1641. Vari ous authors have concluded that he was eldest son of Sir Francis Baildon of Kip pax in the West Riding of Yorkshire,' but, as Jacobus noted, "Richard Belden's estate was small, and his social position not what we should expect if he were son of a knight."2 "Some of this evidence fits the theory, but in toto does not seem to the editor [Jacobus] to make out a very impressive case." But no definitive dis proof had been found. After voicing general objections, Jacobus concluded: However, it is never wise to assume that a theory is incorrect merely because it has romantic and somewhat improbable elements; and while the editor is not personally impressed favorably with the Kippax theory, he would not be understood as dogmatically expressing a negative verdict. The proper verdict is: ''unproved; somewhat improbable; just possibly true."3 . A more recent study by Donald E. Poste established that the immigrant Rich ard Belden had indeed come from Yorkshire, and had lived in the chapelry of Heptonstall in the parish of Halifax. At the conclusion of his summary, Poste stated, "I shall not be able to perform further research on this subject but present these clues in the hope that someone else may be able and willing to follow through."4 Identifying the two Richards as the same person-based on the circumstantial evidence then known-did not seem entirely implausible. -

Signposts to Prehistory

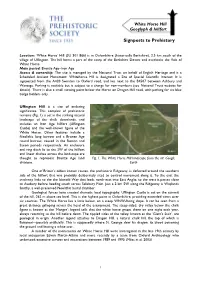

White Horse Hill Geoglyph & hillfort Signposts to Prehistory Location: ‘White Horse’ Hill (SU 301 866) is in Oxfordshire (historically Berkshire), 2.5 km south of the village of Uffington. The hill forms a part of the scarp of the Berkshire Downs and overlooks the Vale of White Horse. Main period: Bronze Age–Iron Age Access & ownership: The site is managed by the National Trust on behalf of English Heritage and is a Scheduled Ancient Monument. Whitehorse Hill is designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest. It is signposted from the A420 Swindon to Oxford road, and lies next to the B4507 between Ashbury and Wantage. Parking is available but is subject to a charge for non-members (see National Trust website for details). There is also a small viewing point below the Horse on Dragon Hill road, with parking for six blue badge holders only. Uffington Hill is a site of enduring significance. This complex of prehistoric remains (Fig. 1) is set in the striking natural landscape of the chalk downlands, and includes an Iron Age hillfort (Uffington Castle) and the well-known figure of the White Horse. Other features include a Neolithic long barrow and a Bronze Age round barrow, reused in the Roman and Saxon periods respectively. An enclosure and ring ditch lie to the SW of the hillfort and linear ditches across the landscape are thought to represent Bronze Age land Fig. 1. The White Horse Hill landscape from the air. Google divisions. Earth One of Britain’s oldest known routes, the prehistoric Ridgeway, is deflected around the southern side of the hillfort that was probably deliberately sited to control movement along it. -

Collections Guide 2 Nonconformist Registers

COLLECTIONS GUIDE 2 NONCONFORMIST REGISTERS Contacting Us What does ‘nonconformist’ mean? We recommend that you contact us to A nonconformist is a member of a religious organisation that does not ‘conform’ to the Church of England. People who disagreed with the book a place before visiting our beliefs and practices of the Church of England were also sometimes searchrooms. called ‘dissenters’. The terms incorporates both Protestants (Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, Independents, Congregationalists, Quakers WYAS Bradford etc.) and Roman Catholics. By 1851, a quarter of the English Margaret McMillan Tower population were nonconformists. Prince’s Way Bradford How will I know if my ancestors were nonconformists? BD1 1NN Telephone +44 (0)113 393 9785 It is not always easy to know whether a family was Nonconformist. The e. [email protected] 1754 Marriage Act ordered that only marriages which took place in the Church of England were legal. The two exceptions were the marriages WYAS Calderdale of Jews and Quakers. Most people, including nonconformists, were Central Library therefore married in their parish church. However, nonconformists often Northgate House kept their own records of births or baptisms, and burials. Northgate Halifax Some people were only members of a nonconformist congregation for HX1 1UN a short time, in which case only a few entries would be ‘missing’ from Telephone +44 (0)1422 392636 the Anglican parish registers. Others switched allegiance between e. [email protected] different nonconformist denominations. In both cases this can make it more difficult to recognise them as nonconformists. WYAS Kirklees Central Library Where can I find nonconformist registers? Princess Alexandra Walk Huddersfield West Yorkshire Archive Service holds registers from more than a HD1 2SU thousand nonconformist chapels. -

Collections Guide 2 Nonconformist Registers

COLLECTIONS GUIDE 2 NONCONFORMIST REGISTERS Contacting Us What does ‘nonconformist’ mean? Please contact us to book a place A nonconformist is a member of a religious organisation that does not ‘conform’ to the Church of England. People who disagreed with the before visiting our searchrooms. beliefs and practices of the Church of England were also sometimes called ‘dissenters’. The terms incorporates both Protestants (Baptists, WYAS Bradford Methodists, Presbyterians, Independents, Congregationalists, Quakers Margaret McMillan Tower etc.) and Roman Catholics. By 1851, a quarter of the English Prince’s Way population were nonconformists. Bradford BD1 1NN How will I know if my ancestors were nonconformists? Telephone +44 (0)113 535 0152 e. [email protected] It is not always easy to know whether a family was Nonconformist. The 1754 Marriage Act ordered that only marriages which took place in the WYAS Calderdale Church of England were legal. The two exceptions were the marriages Central Library & Archives of Jews and Quakers. Most people, including nonconformists, were Square Road therefore married in their parish church. However, nonconformists often Halifax kept their own records of births or baptisms, and burials. HX1 1QG Telephone +44 (0)113 535 0151 Some people were only members of a nonconformist congregation for e. [email protected] a short time, in which case only a few entries would be ‘missing’ from the Anglican parish registers. Others switched allegiance between WYAS Kirklees different nonconformist denominations. In both cases this can make it Central Library more difficult to recognise them as nonconformists. Princess Alexandra Walk Huddersfield Where can I find nonconformist registers? HD1 2SU Telephone +44 (0)113 535 0150 West Yorkshire Archive Service holds registers from more than a e. -

Original Manuscripts

Hebden Bridge Local History Society Archive catalogue ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPTS OM 1/M Transcript of accounts for Wadsworth Surveyor of the Highways 1731-1756; 1757-1769. Vol.1. [By Barber Gledhill?].[n.d.]. OM 2/M Transcript of accounts for Wadsworth Surveyor of the Highways 1769-1776. Vol.2. [Contains two entries for 1777]. [By Barber Gledhill?].[n.d.]. OM 3/M Transcript of accounts for Wadsworth Surveyor of the Highways 1776-1779. Vol.3. [Includes entries for 1780].[By Barber Gledhill?].[n.d.].[ OM 4/M Transcript of accounts for Wadsworth Surveyor of the Highways 1779-1781. Vol.4. [By Barber Gledhill].[n.d.]. Also includes: Accounts for Wadsworth Constables 1772-1781 Accounts for Highway Surveyors and Constables for Midgley 1741-1769 Accounts for Highway Surveyors for Todmorden 1737-1766 Accounts for Highway Surveyors for Walsden 1747-1870 Transcripts of deeds relating to Spinks Hill and its use as a workhouse. OM 5/M Wadsworth Constable Accounts 1732-1782. [n.d.]. OM 6/M Notes on Surveyors of Highways.Includes Accounts of Heptonstall Surveyors 1716-1835 and Heptonstall Constables 1776/77-1818/19.[n.d.]. OM 7/M English Poor Law History.Notes on book by S. and B. Webb.[n.d.]. Poor Relief prior to 1597 The King's Highway The Parish and the County OM 8/M Transcripts of Appleyard Deeds.Transcribed by Barber Gledhill. 1953. Old deeds relating to the White Lion Several of Cockcroft's of Mayroyd wills. Partition deeds of 1773 & 1785 OM 9/M Local History.Notes by Barber Gledhill. 1955. OM 10/M Field Names of Heptonstall.