National Parks for Scotland Could Best Operate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weekly List of Valid Planning Applications Week Ending 13 June 2014

Weekly Planning list for 13 June 2014 Page 1 Argyll and Bute Council Planning Weekly List of Valid Planning Applications Week ending 13 June 2014 13/6/2014 10:5 Weekly Planning list for 13 June 2014 Page 2 Bute and Cowal Reference: 14/01057/PPP Officer: Br ian Close Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 20 - Cowal Community Council: Dunoon Community Council Proposal: Redevelopment of for mer garden centre to for m amixed resi- dential development with associated amenity and parking spa- ces along with a newpublic square Location: Former Garden Centre,6Mar ine Parade,Kir n, Dunoon, Argyll And Bute,PA23 8HE Applicant: Dr ummond Park Dev elopments Ltd Ecclesmachan House,Ecclesmachan, EH52 6NJ,West Loth- ian Ag ent: Mosaic Architecture 100 West Regent Street, Glasgow, G22QD Development Type: 03B - Housing - Local Grid Ref: 218428 - 677983 Reference: 14/01088/PP Officer: Br ian Close Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 20 - Dunoon Community Council: South CowalCommunity Council Proposal: Erection of dwellinghouse including for mation of vehicular access and installation of private water supply and drainage systems. Location: Land ToSouth Of Glenstriven House,Toward, Dunoon, Argyll And Bute,PA23 7UN Applicant: Mr P Blacker Glenstr iven House,Toward, Dunoon, Argyll And Bute,PA23 7UN Ag ent: CDenovan 19 Eccles Road, Hunters Quay, Dunoon, PA23 8LA Development Type: 03B - Housing - Local Grid Ref: 208216 - 678149 Reference: 14/01193/PP Officer: Allocated ToArea Office Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 20 - Dunoon Community Council: South CowalCommunity -

Local Development Plan November 2019

Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park Local Development Plan Action Programme November 2019 Local Development Plan | Action Programme | 1 CONTENTS 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 3 2. Summary of Site Progress over last two years………………………….…………………….4 3. Vision and Development Strategy ...................................................................................... 5 4. Strategic Growth Areas (Arrochar, Balloch & Callander) ................................................. 9 5. Placemaking Priorities in other Towns and Villages ......................................................... 23 6. Rural Development Frameworks ........................................................................................ 29 7. Allocated Sites in Towns and Villages excluding Strategic Growth Areas ..................... 33 8. Completed Allocated Sites………………………………………………………………………...49 9. Strategic Transport Infrastructure ..................................................................................... 50 10. Local Development Plan Policies and Statutory and Planning Guidance ....................... 51 Local Development Plan | Action Programme | 2 1. INTRODUCTION This Action Programme accompanies the Local Development Plan (the Plan) and identifies the actions needed to implement and deliver the development proposals (allocated sites), strategic growth areas and placemaking priorities contained within the Plan. These actions involve a range -

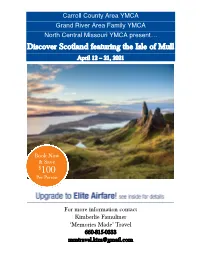

Discover Scotland Featuring the Isle of Mull

Carroll County Area YMCA Grand River Area Family YMCA North Central Missouri YMCA present… Discover Scotland featuring the Isle of Mull April 12 – 21, 2021 Book Now & Save $100 Per Person For more information contact Kimberlie Famuliner ‘Memories Made’ Travel 660-815-0333 [email protected] 10 Days ● 14 Meals: 8 Breakfasts, 6 Dinners Book Now & Save $100 Per Person: Double $4,099; Double $3,999* Single $4,599; Single $4,499; Triple $4,069 Triple $3,969 For bookings made after Oct 21, 2020 call for rates. Included in Price: Round Trip Air from Kansas City Intl Airport, Air Taxes and Fees/Surcharges, Hotel Transfers Non-YMCA member welcome - (please add $50 to quoted rates) Carroll County Area YMCA use code C001 Grand River Area Family YMCA use code G002 North Central Missouri YMCA use code N003 Not included in price: Cancellation Waiver and Insurance of $329 per person * All Rates are Per Person and are subject to change, based on air inclusive package from MCI Upgrade your in-flight experience with Elite Airfare Additional rate of: Business Class $4,290 † Refer to the reservation form to choose your upgrade option IMPORTANT CONDITIONS: Your price is subject to increase prior to the time you make full payment. Your price is not subject to increase after you make full payment, except for charges resulting from increases in government-imposed taxes or fees. Once deposited, you have 7 days to send us written consumer consent or withdraw consent and receive a full refund. (See registration form for consent.) Collette’s Flagship: Collette’s tours open the door to a world of amazing destinations. -

Our Strategic Plan

Our Strategic Plan 2020 to 2023 Contents Foreword 03 Why land matters 04 Land, the economy and inequality 04 Land and human rights 05 Land and climate change 05 Land reform and the Scottish Land Commission 06 Who we are and what we do 06 Our strategy 07 What we will deliver 08 How we will deliver this strategic plan 11 Programme of work 12 Creating the organisation we want to be 13 Financial strategy 14 Measuring success 15 Annex 1 – Programme of work 16 Loch an Eilein, Cairngorms National Park Strategic Plan 2020-23 02 FOREWORD Scotland’s shared national focus This decade must also see significant shifts to over the coming three years will meet Scotland’s ambitious climate targets for 2030, to be on track for a net zero economy by be recovery and renewal following 2045. Changing the way we use land is key to Covid-19, and this strategic plan meeting these targets. As part of a just transition, responds to that challenge. we must meet the pace and scale of change needed and make these changes in ways that This plan sets out how we will support a fair are fair and create economic opportunities. and green recovery to a ‘wellbeing economy’ (see below), helping to create a Scotland which: At the same time, Scotland will be dealing with the implications of the UK’s exit from Glasgow Commonwealth Games Athletes’ Village © Tom Manley • Promotes inclusive economic growth the European Union, including changes in environmental governance frameworks, trade, • Reduces inequality and looking beyond the Common Agricultural • Supports climate action and a just transition Policy – all of which may have significant effects for land use and land markets. -

CAIRNGORMS NATIONAL PARK / TROSSACHS NATIONAL PARK Wildlife Guide How Many of These Have You Spotted in the Forest?

CAIRNGORMS NATIONAL PARK / TROSSACHS NATIONAL PARK Wildlife GuidE How many of these have you spotted in the forest? SPECIES CAIRNGORMS NATIONAL PARK Capercaillie The turkey-sized Capercaillie is one of Scotland’s most characteristic birds, with 80% of the UK's species living in Cairngorms National Park. Males are a fantastic sight to behold with slate-grey plumage, a blue sheen over the head, neck and breast, reddish-brown upper wings with a prominent white shoulder flash, a bright red eye ring, and long tail. Best time to see Capercaille: April-May at Cairngorms National Park Pine Marten Pine martens are cat sized members of the weasel family with long bodies (65-70 cm) covered with dark brown fur with a large creamy white throat patch. Pine martens have a distinctive bouncing run when on the ground, moving front feet and rear feet together, and may stop and stand upright on their haunches to get a better view. Best time to see Pine Martens: June-September at Cairngorms National Park Golden Eagle Most of the Cairngorm mountains have just been declared as an area that is of European importance for the golden eagle. If you spend time in the uplands and keep looking up to the skies you may be lucky enough to see this great bird soaring around ridgelines, catching the thermals and looking for prey. Best time to see Golden Eagles: June-September in Aviemore Badger Badgers are still found throughout Scotland often in surprising numbers. Look out for the signs when you are walking in the countryside such as their distinctive paw prints in mud and scuffles where they have snuffled through the grass. -

A Summary of Recent Research at Glen Tanar Estate, Aberdeenshire, Scotland

International Forest Fire News (IFFN) No. 30 (January – June 2004, 84-93) Prescribed Fire in a Scottish Pinewood: a Summary of Recent Research at Glen Tanar Estate, Aberdeenshire, Scotland Summary The role of natural disturbance in maintaining important ecological processes in natural Scots Pine woodland is becoming increasingly recognised. With increasing pressure to secure the future of pinewood species such as the Capercaillie (Tetrao urugallis), it has become necessary to develop innovative management techniques to manipulate habitat conditions in the absence of browsing pressure. The use of prescribed fire is one of the most promising such management techniques, and is widely used for resource management in similar ecosystems in North America and Australia. Preliminary research conducted at Glen Tanar Estate has demonstrated the potential benefits of prescribed burning, and has produced a number of useful insights to help shape the development of this technique in Scotland. Introduction The complex role of fire in the ecology of natural Scots’ pine forest is well documented for many parts of its extensive distribution (Goldammer and Furyaev 1996), where fire is accepted as an important natural factor in the maintenance of a mosaic of forest types at the landscape scale. In Scotland, however, fire has generally been ignored as an ecological variable even though it has potentially positive attributes. This is presumably because the negative impacts of fire on native woodland have historically been very serious (Steven and Carlisle 1959) and there is an understandable fear of wildfire and its risks to person and property. Also the likelihood of fire occurring and its consequent ecological importance as a disturbance event is easily overlooked the oceanic climate of the United Kingdom. -

Human Rights and the Work of the Scottish Land Commission

Human Rights and the Work of the Scottish Land Commission A discussion paper Dr Kirsteen Shields May 2018 LAND LINES A series of independent discussion papers on land reform issues Background to the ‘Land Lines’ discussion papers The Scottish Land Commission has commissioned a series of independent discussion papers on key land reform issues. These papers are intended to stimulate public debate and to inform the Commission’s longer term research priorities. The Commission is looking at human rights as it is inherent in Scotland’s framework for land reform and underpins our Strategic Plan and Programme of Work. This, the fifth paper in the Land Lines series, is looking at the opportunities provided by land reform for further realisation of economic, social and cultural human rights. The opinions expressed, and any errors, in the papers are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Commission. About the Author Dr Kirsteen Shields is a Lecturer in International Law at the University of Edinburgh’s Global Academy on Agriculture and Food Security and was recently a Fullbright / Royal Society of Edinburgh Scholar at the University of Berkeley, California. She has advised the Scottish Parliament on land reform and human rights and was the first Academic Fellow to the Scottish Parliament’s Information Centre (SPICe) in 2016. LAND LINES A series of independent discussion papers on land reform issues Summary Keywords Community; property rights; land; human rights; economic; social; cultural Background This report provides a primer on key human rights developments and obligations relevant to land reform. It explains the evolution in approach to human rights that is embodied in the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 and it applies that approach to aspects of the Scottish Land Commission’s four strategic priorities. -

Weekly List 05Wc 030220 (255.5

Weekly Planning Schedule Week Commencing: 3 February 2020 Week Number: 5 CONTENTS 1 Valid Planning Applications Received 2 Delegated Officer Decisions 3 Committee Decisions 4 Planning Appeals 5 Enforcement Matters 6 Land Reform (Scotland) Act Section 11 Access Exemption Applications 7 Other Planning Issues 8 Byelaw Exemption Applications 9 Byelaw Authorisation Applications National Park Authority Planning Staff If you have enquiries about new applications or recent decisions made by the National Park Authority you should contact the relevant member of staff as shown below. If they are not available, you may wish to leave a voice mail message or contact our Planning Information Line on 01389 722024. Telephone Telephone PLANNING SERVICES DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT (01389) (01389) Director of Rural Development and Development & Implementation Manager Planning Bob Cook 722631 Stuart Mearns 727760 Performance and Support Manager Catherine Stewart 727731 DEVELOPMENT PLANNING Planners - Development Management Vivien Emery (Mon - Wed) 722619 Alison Williamson 722610 Development Planning and Caroline Strugnell 722148 Communities Manager Julie Gray (Maternity Leave) 727753 Susan Brooks 722615 Amy Unitt 722606 Craig Jardine 722020 Planners - Development Planning Kirsty Sweeney (Mon, Tues, Wed, Fri) 722622 Derek Manson 707705 Planning Assistants Development Planning Assistant Nicola Arnott 722661 Amanda Muller 727721 Lorna Gray 727749 Planner - Development Planning Planning Support (Built Environment Lead) Mary Cameron (Tues – Fri) 722642 Vacant Lynn -

Wester Ross Ros An

Scottish Natural Heritage Explore for a day Wester Ross Ros an lar Wester Ross has a landscape of incredible beauty and diversity Historically people have settled along the seaboard, sustaining fashioned by a fascinating geological history. Mountains of strange, themselves by combining cultivation and rearing livestock with spectacular shapes rise up from a coastline of diverse seascapes. harvesting produce from the sea. Crofting townships, with their Wave battered cliffs and crevices are tempered by sandy beaches small patch-work of in-bye (cultivated) fields running down to the or salt marsh estuaries; fjords reach inland several kilometres. sea can be found along the coast. The ever changing light on the Softening this rugged landscape are large inland fresh water lochs. landscape throughout the year makes it a place to visit all year The area boasts the accolade of two National Scenic Area (NSA) round. designations, the Assynt – Coigach NSA and Wester Ross NSA, and three National Nature Reserves; Knockan Crag, Corrieshalloch Symbol Key Gorge and Beinn Eighe. The North West Highland Geopark encompasses part of north Wester Ross. Parking Information Centre Gaelic dictionary Paths Disabled Access Gaelic Pronunciation English beinn bayn mountain gleann glyown glen Toilets Wildlife watching inbhir een-er mouth of a river achadh ach-ugh field mòr more big beag bake small Refreshments Picnic Area madainn mhath mat-in va good morning feasgar math fess-kur ma good afternoon mar sin leat mar shin laht goodbye Admission free unless otherwise stated. 1 11 Ullapool 4 Ullapul (meaning wool farm or Ulli’s farm) This picturesque village was founded in 1788 as a herring processing station by the British Fisheries Association. -

Balquhidder General Register of the Poor 1889-1929 (PR/BQ/4/1)

Balquhidder General Register of the Poor 1889-1929 (PR/BQ/4/1) 1st Surname 2nd Surname Forename(s) Gender Age Place of Origin Date of Entry Residence Status Occupation Bain Morris Elizabeth F 51 Kilmadock 1920, 27 Jul Toll House, Glenogle Widow House duties Braid Jane Isabella F 54 Dundurer Mill, Comrie 1912, 23 Feb 5 Eden St, Dundee Single House servant Cameron Alexander M 70 Balquhidder 1917, 7 Dec Kipp Farm, Strathyre Single Farmer Campbell Janet F 48 Balquhidder 1915, 7 Dec Stronvar, Balquhidder Single Outworker Campbell Annie F 44 Balquhidder 1909, 15 Mar Black Island Cottages, Stronvar Single Outdoor worker Campbell Ann F 40 Balquhidder 1905 Black Island Cottages, Stronvar Single Domestic Campbell McLaren Janet F 61 Balquhidder 1903, 6 Jun Strathyre Single Servant Campbell Colin M 20 Comrie 27 Aug ? Edinchip Single Farm servant Carmichael Frederick M 48 Liverpool 1919, 7 May Poorhouse Single Labourer Carmichael Ferguson Janet F 72 Balquhidder 1904, 9 Dec Strathyre Widow Domestic Christie Lamont Catherine F 27 Ballycastle, Ireland 1891, 16 Dec Stirling District Asylum Married Currie McLaren Margaret F 43 Kirkintilloch 1910, 29 Jul Newmains, Wishaw Widow House duties Dewar James M 38 Balquhidder 1913, 10 Dec Post Office, Strathyre Single Grocer & Postmaster Ferguson Janet F 77 Balquhidder 1927, 26 May Craigmore, Strathyre Single House duties Ferguson Janet F 53 Aberfoyle 1913, 6 May Stronvar, Balquhidder Widow Charwoman & Outworker Ferguson John M 52 Balquhidder 1900, 9 Jul Govan Asylum Single Hotel Porter Ferguson Minnie F 11 Dumbarton -

James Hawkins 2009 the Chronicles of the Straight Line Ramblers Club

The Chronicles of the Straight Line Ramblers Club James Hawkins 2009 The Chronicles of the Straight Line Ramblers Club James Hawkins SW1 GALLERY 12 CARDINAL WALK LONDON SW1E 5JE James and Flick Hawkins would like to thank The John Muir Trust (www.jmt.org) and Knoydart Foundation (www.knoydart-foundation.com) for their support Design Peter A Welch (www.theworkhaus.com) MAY 2009 Printed J Thomson Colour Printers, Inverness, IV3 8GY The Straight Line Ramblers Club Don’t get me wrong, I am most enthusiastic about technology and its development; I am very happy to be writing this on my new PC that also helps me enormously with many aspects of my visual work. No it is more that, in our long evolution, at this point there now seems a danger of disconnection from The Straight Line Ramblers Club was first conceived when we were teenagers walking our parents the natural world. We have always been controlled by Nature, now we think that we can control it. dogs around the Oxfordshire countryside, membership was flexible, anyone could join and of course the one thing we didn’t do was walk in a straight line. Many of us have kept in touch and when John Muir, whose writings I have discovered during the research for this exhibition, felt that he needed we meet up that spirit of adventure still prevails, there aren’t any rules, but if there were they would to experience the wilderness “to find the Law that governs the relations subsisting between human be that spontaneity is all, planned routes exist to be changed on a whim and that its very impor- beings and Nature.” After many long and often dangerous journeys into wild places he began to tant to see what’s around the next corner or over the next top. -

Argyll and Bute Council Council Legal and Regulatory Support 24 June 2021 Boundaries Scotland

ARGYLL AND BUTE COUNCIL COUNCIL LEGAL AND REGULATORY SUPPORT 24 JUNE 2021 BOUNDARIES SCOTLAND - REVIEW OF ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 A report was submitted to the Council meeting held on 24 September 2020, detailing the terms of a proposed response to Boundaries Scotland’s initial consultation, which ran for a 2 month period from 16th July to 30th September 2020, in regard to the 2019 Review of Electoral Arrangements for Argyll and Bute Council area. The Council agreed the response and this was submitted in accordance with the 30th September 2020 deadline. 1.2 Following the initial consultation with the Council, Boundaries Scotland considered our response and developed proposals for public consultation, which ran for a 12 week period between November 2020 and January 2021. 1.3 Having considered all the comments submitted as part of the public consultation, Boundaries Scotland have now published their final proposals for Argyll and Bute Council area and a copy of the report to Scottish Ministers is attached at appendix 1. If Scottish Ministers are content with the report, it is anticipated that the proposals will be implemented ready for the Local Government elections in May 2022. 1.4 In line with section 18(3) of the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 the Council will make copies of the report available for public inspection at suitable locations and will be publicised on the Council website from 10 June 2021 until 6 months after the making of an Order in the Scottish Parliament giving effect to any proposals in the report. 2.