Adaptive Responses of Animals to Climate Change Are Most Likely Insufficient

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telomere Length Is Repeatable, Shortens with Age and Reproductive

University of Groningen Telomere length is repeatable, shortens with age and reproductive success, and predicts remaining lifespan in a long-lived seabird Bichet, Coraline; Bouwhuis, Sandra; Bauch, Christina; Verhulst, Simon; Becker, Peter H.; Vedder, Oscar Published in: Molecular Ecology DOI: 10.1111/mec.15331 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2020 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Bichet, C., Bouwhuis, S., Bauch, C., Verhulst, S., Becker, P. H., & Vedder, O. (2020). Telomere length is repeatable, shortens with age and reproductive success, and predicts remaining lifespan in a long-lived seabird. Molecular Ecology, 29(2), 429-441. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15331 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Population Substructure, Local Density, and Calf Winter Survival in Red Deer (Cervus Elaphus)

Edinburgh Research Explorer Population substructure, local density, and calf winter survival in red deer (Cervus elaphus) Citation for published version: Coulson, T, Albon, S, Guinness, F, Pemberton, J & CluttonBrock, T 1997, 'Population substructure, local density, and calf winter survival in red deer (Cervus elaphus)', Ecology, vol. 78, no. 3, pp. 852-863. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(1997)078[0852:PSLDAC]2.0.CO;2 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1890/0012-9658(1997)078[0852:PSLDAC]2.0.CO;2 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Ecology Publisher Rights Statement: RoMEO green General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 07. Oct. 2021 Population Substructure, Local Density, and Calf Winter Survival in Red Deer (Cervus Elaphus) Author(s): Tim Coulson, Steve Albon, Fiona Guinness, Josephine Pemberton and Tim Clutton- Brock Source: Ecology, Vol. 78, No. 3 (Apr., 1997), pp. 852-863 Published by: Ecological Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2266064 . -

Science & Policy Meeting Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz Science in The

SUMMER 2014 ISSUE 27 encounters page 9 Science in the desert EMBO | EMBL Anniversary Science & Policy Meeting pageS 2 – 3 ANNIVERSARY TH page 8 Interview Jennifer E M B O 50 Lippincott-Schwartz H ©NI Membership expansion EMBO News New funding for senior postdoctoral In perspective Georgina Ferry’s enlarges its membership into evolution, researchers. EMBO Advanced Fellowships book tells the story of the growth and ecology and neurosciences on the offer an additional two years of financial expansion of EMBO since 1964. occasion of its 50th anniversary. support to former and current EMBO Fellows. PAGES 4 – 6 PAGE 11 PAGES 16 www.embo.org HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE EMBO|EMBL ANNIVERSARY SCIENCE AND POLICY MEETING transmissible cancer: the Tasmanian devil facial Science meets policy and politics tumour disease and the canine transmissible venereal tumour. After a ceremony to unveil the 2014 marks the 50th anniversary of EMBO, the 45th anniversary of the ScienceTree (see box), an oak tree planted in soil European Molecular Biology Conference (EMBC), the organization of obtained from countries throughout the European member states who fund EMBO, and the 40th anniversary of the European Union to symbolize the importance of European integration, representatives from the govern- Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL). EMBO, EMBC, and EMBL recently ments of France, Luxembourg, Malta, Spain combined their efforts to put together a joint event at the EMBL Advanced and Switzerland took part in a panel discussion Training Centre in Heidelberg, Germany, on 2 and 3 July 2014. The moderated by Marja Makarow, Vice President for Research of the Academy of Finland. -

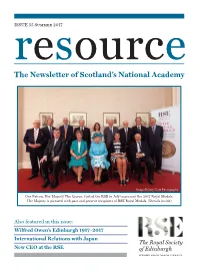

Resource Summer 2017

ISSUE 55 Summer 2017 resourc e The Newsletter of Scotland’s National Academy Image © Gary Doak Photography Our Patron, Her Majesty The Queen, visited the RSE in July to present the 2017 Royal Medals. Her Majesty is pictured with past and present recipients of RSE Royal Medals. (Details inside) Also featured in this issue: Wilfred Owen’s Edinburgh 1917 –2017 International Relations with Japan New CEO at the RSE resourc e Summer 2017 The Royal Visit 2017 We were highly honoured to welcome Her Majesty The Queen to the RSE on Friday 7 July 2017 to present this year’s Royal Medals. Her Majesty was greeted, at the door to 22 George Street, by The Rt Hon Lord Provost and Lord Lieutenant of the City of Edinburgh, Frank Ross. The RSE Royal Medals were instituted by Her Majesty in 2000, to mark the Millennium, and have been awarded since then with her express approval. These accolades are awarded for distinction and international repute in any of the following categories: Life Sciences; Physical and Engineering Sciences; Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences; Business and Commerce. Medals were awarded to: Professor Peter Boyle CorrFRSE FMEDSci (below left), President, International Prevention Research Institute and Director, the University of Strathclyde Institute of Global Public Health, for his outstanding contribution to global cancer control and public health policy; Professor Tessa Holyoake FRSE FMedSci, Director (below right), Paul O’Gorman Leukaemia Research Centre, University of Glasgow, for her outstanding contribution to the field of Life Sciences through her discovery of the existence of cancer stem cells in chronic myeloid leukaemia and her development of a new therapy for this condition; Mr Donald Runnicles OBE (above), Chief Conductor, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, for his outstanding contribution to the art of music at the highest international level. -

General Methods for Evolutionary Quantitative Genetic Inference from Generalized Mixed Models

| INVESTIGATION General Methods for Evolutionary Quantitative Genetic Inference from Generalized Mixed Models Pierre de Villemereuil,* Holger Schielzeth,†,‡ Shinichi Nakagawa,§ and Michael Morrissey**,1 *Laboratoire d’Écologie Alpine, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Unité Mixte de Recherche 5553, Université Joseph Fourier, 38041 Grenoble Cedex 9, France, †Department of Evolutionary Biology, Bielefeld University, 33615 Bielefeld, Germany, ‡Institute of Ecology, Friedrich Schiller University, 07743 Jena, Germany, §Evolution and Ecology Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2052, Australia, and **School of Evolutionary Biology, University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews KY16 9TH, United Kingdom ORCID IDs: 0000-0002-8791-6104 (P.d.V.); 0000-0002-9124-2261 (H.S.); 0000-0002-7765-5182 (S.N.); 0000-0001-6209-0177 (M.M.) ABSTRACT Methods for inference and interpretation of evolutionary quantitative genetic parameters, and for prediction of the response to selection, are best developed for traits with normal distributions. Many traits of evolutionary interest, including many life history and behavioral traits, have inherently nonnormal distributions. The generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) framework has become a widely used tool for estimating quantitative genetic parameters for nonnormal traits. However, whereas GLMMs provide inference on a statistically convenient latent scale, it is often desirable to express quantitative genetic parameters on the scale upon which traits are measured. The parameters of fitted GLMMs, despite being on a latent scale, fully determine all quantities of potential interest on the scale on which traits are expressed. We provide expressions for deriving each of such quantities, including population means, phenotypic (co)variances, variance components including additive genetic (co)variances, and parameters such as heritability. -

Survival, Natural Selection and Foraging Efficiency in Soay Sheep on St

Survival, Natural Selection and Foraging Efficiency in Soay Sheep on St. Kilda. JOCELYN MARGERY MILNER Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London, January 1999. Institute of Zoology, The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NWl 4RY. & Department of Biology, University College London, Gower Street, London, WCIE 6BT. ProQuest Number: 10015690 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10015690 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Survival, Natural Selection and Foraging Efficiency in Soay Sheep on St. Kilda. 4 Soay sheep grazing in the Village Bay study area on Hirta, St. Kilda, in March. Acknowledgements After the disappointment of having to abandon ‘PhD-take one’ due to civil war in Rwanda, in 1993/94, completing this thesis means a lot to me. I am therefore very grateful to all those who have given me a second chance, and helped me to achieve this personal goal. In particular, I would like to thank my small army of supervisors. They have been supportive and involved throughout, teaching me how to approach research and helping me focus on interesting ecological questions. -

Telomere Length Is Repeatable, Shortens with Age and Reproductive Success, and Predicts Remaining Lifespan in a Long-Lived Seabird

Received: 22 August 2019 | Revised: 13 November 2019 | Accepted: 2 December 2019 DOI: 10.1111/mec.15331 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Telomere length is repeatable, shortens with age and reproductive success, and predicts remaining lifespan in a long-lived seabird Coraline Bichet1 | Sandra Bouwhuis1 | Christina Bauch2 | Simon Verhulst2 | Peter H. Becker1 | Oscar Vedder1,2 1Institute of Avian Research, Wilhelmshaven, Germany Abstract 2Groningen Institute for Evolutionary Telomeres are protective caps at the end of chromosomes, and their length is posi- Life Sciences, University of Groningen, tively correlated with individual health and lifespan across taxa. Longitudinal studies Groningen, The Netherlands have provided mixed results regarding the within-individual repeatability of telomere Correspondence length. While some studies suggest telomere length to be highly dynamic and sensi- Coraline Bichet, Institute of Avian Research, Wilhelmshaven, Germany. tive to resource-demanding or stressful conditions, others suggest that between-in- Email: [email protected] dividual differences are mostly present from birth and relatively little affected by the Funding information later environment. This dichotomy could arise from differences between species, but Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, also from methodological issues. In our study, we used the highly reliable Terminal Grant/Award Number: DFG, BE 916/8 & 9; Nederlandse Organisatie voor Restriction Fragment analysis method to measure telomeres over a 10-year period in Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, Grant/ adults of a long-lived seabird, the common tern (Sterna hirundo). Telomeres shortened Award Number: 863.14.010; Alexander von Humboldt with age within individuals. The individual repeatability of age-dependent telomere length was high (>0.53), and independent of the measurement interval (i.e., one vs. -

Smutty Alchemy

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2021-01-18 Smutty Alchemy Smith, Mallory E. Land Smith, M. E. L. (2021). Smutty Alchemy (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/113019 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Smutty Alchemy by Mallory E. Land Smith A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2021 © Mallory E. Land Smith 2021 MELS ii Abstract Sina Queyras, in the essay “Lyric Conceptualism: A Manifesto in Progress,” describes the Lyric Conceptualist as a poet capable of recognizing the effects of disparate movements and employing a variety of lyric, conceptual, and language poetry techniques to continue to innovate in poetry without dismissing the work of other schools of poetic thought. Queyras sees the lyric conceptualist as an artistic curator who collects, modifies, selects, synthesizes, and adapts, to create verse that is both conceptual and accessible, using relevant materials and techniques from the past and present. This dissertation responds to Queyras’s idea with a collection of original poems in the lyric conceptualist mode, supported by a critical exegesis of that work. -

Performance of Marker-Based Relatedness Estimators in Natural Populations of Outbred Vertebrates

Genetics: Published Articles Ahead of Print, published on June 18, 2006 as 10.1534/genetics.106.057331 Performance of marker-based relatedness estimators in natural populations of outbred vertebrates Katalin Csilléry?, Toby Johnson?, Dario Beraldi?, Tim H. Clutton-Brocky Dave Coltmanz, Bengt Hanssonx, Goran Spongy, Josephine Pemberton? ?Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH9 3JT, United King- dom yDepartment of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 3EJ, United Kingdom zDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, T6G 2E9, Canada xDepartment of Animal Ecology, Lund University, 22362 Lund, Sweden 1 Running Head: Performance of relatedness estimators Keywords: Pairwise relatedness, Moment estimators, Pedigrees, Microsatellites, Long-term projects Corresponding author: Katalin Csilléry Institute of Evolutionary Biology The King's Buildings Ashworth Laboratories University of Edinburgh West Mains Road Edinburgh EH9 3JT United Kingdom Phone: +44 131 650 7334 Fax: +44 131 650 6564 Email: [email protected] 2 Abstract Knowledge of relatedness between pairs of individuals plays an important role in many research areas including evolutionary biology, quantitative genetics and conser- vation. Pairwise relatedness estimation methods based on genetic data from highly variable molecular markers are now extensively used as a substitute for pedigrees. Al- though the sampling variance of the estimators have been intensively studied for for the most common simple genetic relationships, such as unrelated, half- and full-sib or parent-offspring, little attention has been paid to the average performance of the esti- mators, by which we mean the performance across all pairs of individuals in a sample. Here we apply two measures to quantify the average performance, first, misclassifica- tion rates between pairs of genetic relationships and, second, the proportion of vari- ance explained in the pairwise relatedness estimates by the true population relatedness composition (i.e. -

Senescence Rates Are Determined by Ranking on the Fast–Slow Life-History Continuum

Ecology Letters, (2008) 11: xxx–xxx doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01187.x LETTER Senescence rates are determined by ranking on the fast–slow life-history continuum Abstract Owen R. Jones,1* Jean-Michel Comparative analyses of survival senescence by using life tables have identified Gaillard,2 Shripad Tuljapurkar,3 Jussi S. generalizations including the observation that mammals senesce faster than similar-sized Alho,4 Kenneth B. Armitage,5 Peter H. birds. These generalizations have been challenged because of limitations of life-table Becker,6 Pierre Bize,7 Jon Brommer,8 approaches and the growing appreciation that senescence is more than an increasing 9,10 Anne Charmantier, Marie probability of death. Without using life tables, we examine senescence rates in annual 10,11 12 Charpentier, Tim Clutton-Brock, individual fitness using 20 individual-based data sets of terrestrial vertebrates with F. Stephen Dobson,13 Marco Festa- contrasting life histories and body size. We find that senescence is widespread in the wild and Bianchet,14 Lars Gustafsson,15 Henrik equally likely to occur in survival and reproduction. Additionally, mammals senesce faster Jensen,16 Carl G. Jones,17 Bo-Go¨ ran Lillandt,4 Robin McCleery,9, Juha than birds because they have a faster life history for a given body size. By allowing us to Merila¨ ,4 Peter Neuhaus,18 Malcolm disentangle the effects of two major fitness components our methods allow an assessment A. C. Nicoll,19 Ken Norris,19 Madan K. of the robustness of the prevalent life-table approach. Focusing on one aspect of life Oli,20 Josephine Pemberton,21 Hannu history – survival or recruitment – can provide reliable information on overall senescence. -

Nhbs Annual New and Forthcoming Titles Issue: 2003 Complete January 2004 [email protected] +44 (0)1803 865913

nhbs annual new and forthcoming titles Issue: 2003 complete January 2004 [email protected] +44 (0)1803 865913 The NHBS Monthly Catalogue in a complete yearly edition Zoology: Mammals Birds Welcome to the Complete 2003 edition of the NHBS Monthly Catalogue, the ultimate Reptiles & Amphibians buyer's guide to new and forthcoming titles in natural history, conservation and the Fishes environment. With 300-400 new titles sourced every month from publishers and research organisations around the world, the catalogue provides key bibliographic data Invertebrates plus convenient hyperlinks to more complete information and nhbs.com online Palaeontology shopping - an invaluable resource. Each month's catalogue is sent out as an HTML Marine & Freshwater Biology email to registered subscribers (a plain text version is available on request). It is also General Natural History available online, and offered as a PDF download. Regional & Travel Please see our info page for more details, also our standard terms and conditions. Botany & Plant Science Prices are correct at the time of publication, please check www.nhbs.com for the Animal & General Biology latest prices. NHBS Ltd, 2-3 Wills Rd, Totnes, Devon TQ9 5XN, UK Evolutionary Biology Ecology Habitats & Ecosystems Conservation & Biodiversity Environmental Science Physical Sciences Sustainable Development Data Analysis Reference Mammals An Affair with Red Squirrels 58 pages | Col photos | Larks Press David Stapleford Pbk | 2003 | 1904006108 | #143116A | Account of a lifelong passion, of the author's experience of breeding red squirrels, and more £5.00 BUY generally of their struggle for survival since the arrival of their grey .... All About Goats 178 pages | 30 photos | Whittet Lois Hetherington, J Matthews and LF Jenner Hbk | 2002 | 1873580606 | #138085A | A complete guide to keeping goats, including housing, feeding and breeding, rearing young, £15.99 BUY milking, dairy produce and by-products and showing. -

Evolution of Maternal Effect Senescence

Evolution of maternal effect senescence Jacob A. Moorad1 and Daniel H. Nussey Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH9 3FL, United Kingdom Edited by James W. Vaupel, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock, Germany, and approved December 4, 2015 (received for review October 23, 2015) Increased maternal age at reproduction is often associated with Amid the many studies of senescing traits, a clear pattern is decreased offspring performance in numerous species of plants emerging that relates maternal age to the health, fitness, and life- and animals (including humans). Current evolutionary theory considers span of their progeny across widely diverse taxa including humans such maternal effect senescence as part of a unified process of (8), birds (9, 10), mammals (11, 12), Drosophila species (13–15) and reproductive senescence, which is under identical age-specific selective other arthropods (16–18), and plants (19). Although observations pressures to fertility. We offer a novel theoretical perspective by com- suggest that maternal effect senescence may not proceed at the – bining William Hamilton’s evolutionary model for aging with a quan- same rate as fertility senescence (12, 20 24), there is no evolu- titative genetic model of indirect genetic effects. We demonstrate that tionary theory yet capable of explaining maternal effect senescence fertility and maternal effect senescence are likely to experience differ- or its distinction from fertility senescence. Biologists have assumed ent patterns of age-specific selection and thus can evolve to take di- that the age-related decline in selection that shapes fertility and survival generalizes to traits under the influence of IGEs, including vergent forms.