Shire of Korong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

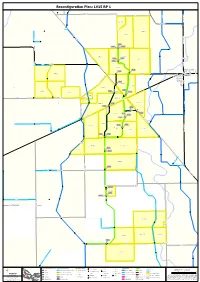

Reconfiguration Plan: LV15 RP 1

Reconfiguration Plan: LV15 RP 1 *# Mills Mills Rd Findlays Rd *# *# Walkers Rd 23/1 13/5/1 *# *# Calivil Creek 22A\PP3108 -Cohuna Pyramid Rd U! *# *# *# Pyramid*# - Mincha Rd U! *# 22/1 *# 23\PP3108 Mitiamo - Kerang Rd 22\PP3108 *# 6/20/1 *# U! GF -MinchaPyramid Rd PH1049 PH1047A PH1049B *# *# *# BoundaryRd *# *# GF GF 91\PP3108 neil St 90\PP3108 O PH1047 PH1046 Truckwash St 92\PP3108 PH1047 *# *# 4/20/1 Gladfield*# Rd GF St Kelly *# GF BoundaryRd Factory Lane Mitiamo - Kerang Rd 91A\PP3108 20/1 Ottrey St PH1045 Mckay St PH1061 *# Victoria St *# 99\PP3108 GF Gladfield Rd # GF *# * BuckleySt GF *# McintyreSt PYRAMID HILL Little Albert St Durham Ox Rdt S y r o Albert St g e r G GF Mcgillivray St PH1060 GF BarberSt *# * 93B\PP3108 # GF 93C\PP3108 BramleySt ^_ 102\PP3108 *# * # PH1042 *# 98\PP3108 PH1059 5/16/1 102A\PP3108 PH1043 Seven Months Creek *# 101\PP3108 *# *# 102F\PP3108 *# 3/20/1 *# U! *# Gladfield South Rd 102D\PP3108 GF *# *# 49B~C\PP3145 49A~C\PP3145 *# 102C\PP3108 40~B\PP3145 ^_GF 49~C\PP3145 PH1058 12/5/1 PH1057 PH1062 6/ 16 Halls Rd Halls 2\TP396148 # 6/16/1 */1 ^_ *# *# PH1063 2\TP245855 PH1062 5/1 *# PH1041 GF M it Boort - Pyramid Rd ia PH1039 m o - !U ^_ K *#U GF e ra n g R d * # *# 1\TP396148 *#GF PH1039 PH1040 13~C\PP3145 1/20/1 1\TP245855 29~C\PP3145 *# 21~C\PP3145 Bendigo -Pyramid Bendigo Rd PH1037 PH1038 * # *# *# 1 1\TP410966 1\TP101916 22~C\PP3145 16/1 PH1032 Cassidys Cassidys Rd 2\TP7739 GF GF PH1033 *#*# *# *# *# GF *#*# 23~C\PP3145 11/5/1 GF *# 10/5/1 U! U! *# PH1030 * # # 18/1 *# * *# Whitewoods*# Rd Mitiamo -

James Watkins

JAMES WATKINS 1821 James Watkins was born circa 1821 at Carmarthen Town, Carmarthenshire, Wales to Thomas Watkins (a blacksmith) and Rachel nee Jones. 06/08/1846 James Watkins married Anne Thomas the daughter of Richard Thomas, a ‘Collier’ in the Registry Office in the district of Merthry Tydfil, Glamorganshire, Wales. At time of marriage James was residing at Tirfounder, Aberdare, occupation - Collier. Ann was residing at Mill Street, Aberdare, occupation - Mantua Maker. 29/01/1848 James and Anne Watkins welcomed the birth of their first child a son, William Watkins who was born at the family home in Cae Melyn, Aberdare, Glamorgan, Wales. The birth certificate records James' occupation as 'Collier'. 02/09/1850 James and Anne Watkins welcomed the birth of their second child a daughter, Mary Watkins who was born at the family home on Cardiff Road, Aberdare, Glamorgan, Wales. The birth certificate records James’ occupation as 'Miner'. 1851 From the Welsh Census: James Watkins, aged 30 was recorded living at Aberaman Road, Walwen with his wife Anne and their two children William and Mary. 1855 About 1855, notations made on the death certificates of James and Anne show that a third child was born whom they named Elizabeth. It is not known what happened to baby Elizabeth but it appears she died the same year or could have been a still born baby. 05/09/1855 James Watkins sailed out of Liverpool, Lancashire, England with his wife Anne and their two children William and Mary on board the sailing ship, ‘Lightning’, bound for Australia. 25/11/1855 James Watkins, his wife and their two children William and Mary sailed into Hobson’s Bay, Melbourne on board the sailing ship, ‘Lightning’. -

Low Res April 2021 About Boort

EDITION 197 April 2021 Contact BRIC on 5455 2716 or email [email protected] to receive the ‘About Boort’ via email. Serving Our Local Community ABOUT BOORT/BRIC PHOTO COMPETITION See page 14 Great prizes DAYLIGHT SAVINGS ENDS 4TH APRIL– CLOCKS GO BACK AN HOUR When local daylight time is about to reach Sunday, 4 April 2021, 3:00 am clocks are turned backward 1 hour to 2:00 am MAYORAL COLUMN benefit to the Boort Memorial 1 March 2021 Hall as well as many other buildings around town. He has always been a champion for the hall, making sure it was in good Circuit Breaker Action Business Support Package condition and ready for use – Last week the Victorian Premier announced a $143 demonstrating Ivan’s dedication million Circuit Breaker Support Package for eligible to his local community. businesses impacted by the recent COVID-19 circuit The local historical society is breaker action. currently interviewing Ivan There are four initiatives available for eligible about the work he has completed in the Boort area businesses as part of this support package: the with the local halls. Business Costs Assistance Program, Licensed Hospitality Venue Fund – Circuit Breaker Action ABS looking for field managers Payment, Victorian Accommodation Support The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) is currently Program, and Travel Voucher schemes. recruiting for field managers in our local area for the For more information regarding the support package next Census on 10 August 2021. and initiatives, visit www.business.vic.gov.au/support Census Field Managers play a critical role in helping -for-your-business/grants-and-assistance/circuit- their local community to complete the Census, and breaker-action-business-support-package community participation in the Census is vital. -

Special Report No. 4

AOP Gf^ Auditor-General VICTORIA of Victoria Special Report No 4 ''XJ# Court Closures Si-/ ?^' Victoria ^^ November 1986 VICTORIA Report of the Auditor - General SPECIAL REPORT No 4 Court Closures in Victoria Ordered by the Legislative Assembly to be printed MELBOURNE F D ATKINSON GOVERNMENT PRINTER 1985-86 No. 130 .v^°%°^^. 1 MACARTHUR STREET MELBOURNE, VIC. 3002 VICTORIA The Honourable the Speaker, November 19 86 Legislative Assembly, Parliament House, MELBOURNE 3000 Sir, Pursuant to the provisions of Section 48 of the Audit Act 1958, I hereby transmit a report concerning court closures in Victoria. The primary purpose of conducting reviews of this nature is to provide an overview as to whether public funds in programs selected for examination, are being spent in an economic and efficient manner consistent with government policies and objectives. Constructive suggestions are also provided in line with the ongoing process of modifying and improving financial management and accountability controls within the public sector. I am pleased to advise that this review has already proven to be of benefit to the government departments involved, as evidenced by their positive replies detailing initiatives already undertaken or evolving. I am also hopeful that this report will assist in resolving other issues, including the development of a policy on the use and management of public buildings. The co-operation and assistance received by my staff from the departments during the course of the review was appreciated. It is my view that there is a growing awareness by government agencies of the advantages to be gained from such reviews, particularly the provision of independent advice on areas of concern. -

The Geology and Prospectivity of the Southern Margin of the Murray Basin

VIMP Report 4 The geology and prospectivity of the southern margin of the Murray Basin by M.D. BUSH, R.A. CAYLEY, S. ROONEY, K. SLATER, & M.L. WHITEHEAD March 1995 Bibliographic reference: BUSH, M.D., CAYLEY, R.A., ROONEY, S., SLATER, K., & WHITEHEAD, M.L., 1995. The geology and prospectivity of the southern margin of the Murray Basin. Geological Survey of Victoria. VIMP Report 4. © Crown (State of Victoria) Copyright 1995 Geological Survey of Victoria ISSN 1323 4536 ISBN 0 7306 7412 6 This report and attached map roll may be purchased from: Business Centre, Department of Agriculture, Energy & Minerals, Ground Floor, 115 Victoria Parade, Fitzroy 3065 For further technical information contact: General Manager, Geological Survey of Victoria, P O Box 2145, MDC Fitzroy 3065 Acknowledgments The preparation of this report has benefited from discussions with a number of colleagues from the Geological Survey of Victoria, notably David Taylor, Alan Willocks, Roger Buckley and Iain McHaffie. The authors would also like to thank Gayle Ellis for the formatting and Roger Buckley for the editing of this report. GEOLOGY AND PROSPECTIVITY - SOUTHERN MARGIN MURRAY BASIN 1 CONTENTS Abstract 3 1 Introduction 4 2 Geological history 5 2.1 Adelaide Fold Belt 5 2.2 Lachlan Fold Belt 5 3 Summary of rock units 8 3.1 Early to Middle Cambrian (The Glenelg Zone) 8 3.2 Middle to Late Cambrian (The Glenelg Zone and the Stawell Zone) 8 3.3 Cambro-Ordovician (The Stawell Zone) 9 3.4 Ordovician (The Glenelg Zone) 10 3.5 Ordovician (The Bendigo-Ballarat Zone) 10 3.6 Late -

BENDIGO EC U 0 10 Km

Lake Yando Pyramid Hill Murphy Swamp July 2018 N Lake Lyndger Moama Boort MAP OF THE FEDERAL Little Lake Boort Lake BoortELECTORAL DIVISION OF Echuca Woolshed Swamp MITIAMO RD H CA BENDIGO EC U 0 10 km Strathallan Y RD W Prairie H L O Milloo CAMPASPE D D I D M O A RD N Timmering R Korong Vale Y P Rochester Lo d d o n V Wedderburn A Tandarra N L R Greens Lake L E E M H IDLAND Y ek T HWY Cre R O Corop BENDIGO Kamarooka East N R Elmore Lake Cooper i LODDON v s N H r e W e O r Y y r Glenalbyn S M e Y v i Kurting N R N E T Bridgewater on Y Inglewood O W H Loddon G N I Goornong O D e R N D N p C E T A LA s L B ID a H D M p MALLEE E E R m R Derby a Huntly N NICHOLLS Bagshot C H Arnold Leichardt W H Y GREATER BENDIGO W Y WIMM Marong Llanelly ERA HWY Moliagul Newbridge Bendigo M Murphys CIVOR Tarnagulla H Creek WY Redcastle STRATHBOGIE Strathfieldsaye Knowsley Laanecoorie Reservoir Lockwood Shelbourne South Derrinal Dunolly Eddington Bromley Ravenswood BENDIGO Lake Eppalock Heathcote Tullaroop Creek Ravenswood South Argyle C Heathcote South A L D locality boundary E Harcourt R CENTRAL GOLDFIELDS Maldon Cairn Curran Dairy Flat Road Reservoir MOUNT ALEXANDER Redesdale Maryborough PYRENEES Tooborac Castlemaine MITCHELL Carisbrook HW F Y W Y Moolort Joyces Creek Campbells Chewton Elphinstone J Creek Pyalong o Newstead y c Strathlea e s Taradale Talbot Benloch locality MACEDON Malmsbury boundary Caralulup C RANGES re k ek e re Redesdale Junction C o Kyneton Pastoria locality boundary o r a BALLARAT g Lancefield n a Clunes HEPBURN K Woodend Pipers Creek -

North-West-Victoria-Historic-Mining-Plots-Dunolly

NORTH WEST VICTORIA HISTORIC MINING PLOTS (DUNOLLY, HEATHCOTE, MALDON AND RUSHWORTH) 1850-1980 Historic Notes David Bannear Heritage Victoria CONTENTS: Dunolly 3 Heathcote 48 Maldon 177 Rushworth 268 DUNOLLY GENERAL HISTORY PHASE ONE 1853/55: The Moliagul Police Camp had been down at the bottom end of Commissioners Gully near Burnt Creek from January 1853 until June 1855. This camp included a Sub Inspector, two Sergeants, a Corporal, six mounted and twelve-foot Constables, a Postmaster, Clerk and Tent Keeper. For a while this was the headquarters for the entire Mining District. 1 1853 Moliagul: Opened in 1853 along with Surface Gully. Their richness influenced the moving of the settlement from Commissioners Gully to where the township is now. 2 1853: Burnt Creek, the creek itself, was so-called before gold digging started, but Burnt Creek goldfield, situated about two miles south of Dunolly, started with the discovery of gold early in 1853, and at a rush later that year ... Between August and October 1853 the Commissioners’ Camp at Jones Creek was shifted to Burnt Creek, where there had been a rush ... By April 1854 there had been an increase in population at Burnt Creek, and there were 400 diggers there in July. Digging was going on in Quaker’s Gully and two large nuggets were found there in 1854, by October there were 900 on the rush, and the Bet Bet reef was discovered. By November 1854 the gold workings extended three miles from Bet Bet to Burnt Creek and a Commissioners’ Camp was started at Bet Bet, near where Grant’s hotel was later. -

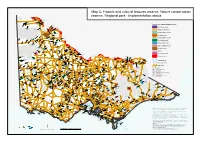

Map C: Historic and Cultural Features Reserve, Nature Conservation Reserve, Regional Park - Implementation Status

Map C: Historic and cultural features reserve, Nature conservation reserve, Regional park - implementation status Merbein South FR Psyche Bend Pumps HCF R Mildura FFR Yarrara Yatpool FFR FR Lambert Island NCR Historic and cultural features reserve Karadoc Bum bang Island Meringur NCR HCF R FFR Toltol Fully implemented FFR Lakes Powell and Carpul Wemen Mallanbool NCR FFR Nowingi Ironclad C atchment FFR and C oncrete Tank Partially implemented HR Bannerton FFR Wandown Implementation unclear Moss Tank FFR Annuello FFR FFR Bolton Kattyoong Tiega FFR Unimplemented FR FR Kulwin FFR Degraves Tank FR Kulwin Manya Wood Wood Gnarr FR Cocamba Nature conservation reserve FR Walpeup Manangatang FFR Dunstans Timberoo Towan Plains FR FFR (Lulla) FFR FFR FFR FFR Bronzewing FFR Fully implemented Murrayville FFR Chinkapook FR FFR Yarraby Chillingollah FR Koonda Nyang FFR FR Boinka FFR Lianiduck Partially implemented FR FFR Welshmans Plain FFR Dering FFR Turriff Lake Timboram FFR Waitchie FFR Implementation unclear FFR Winlaton Yetmans (Patchewollock) Wathe NCR FFR FFR Green Yassom Swamp Dartagook Unimplemented NCR Lake NCR Koondrook Paradise RP Brimy Bill Korrak Korrak HC FR FFR WR NCR Cambacanya Angels Rest Wandella Kerang RP Regional park Lake FFR FR NCR Gannawarra Red Gum Albacutya Swamp V NCR Cohuna HCFR RP Wangie FFR Tragowel Swamp Pyramid Creek Cohuna Old Fully implemented NCR Cannie NCR NCR Court House Goyura Rowland HCF R HR Towaninny NCR Flannery Red Bluff Birdcage NCR Griffith Lagoon NCR Bonegilla Unimplemented FFR NCR Bethanga FFR Towma (Lake -

Loddon Mallee Regional Dementia Management Strategy

Loddon Shire, List of Dementia services April 2014 This booklet of Dementia services available in the Loddon Shire was produced as part of the “Improving the Dementia Care Journey” project funded by the Victorian Department of Human Services in 2007. Information has been updated and is correct at time of printing May 2014. Much of the service information has been reproduced from www.connectingcare.com. This booklet will be updated periodically. For an updated booklet please email: [email protected] Or phone Angela Crombie (03) 5454 6415 [email protected] Or phone Evan Stanyer (03) 5454 6415 This booklet was originally produced in 2007 by Angela Crombie, Project manager, Collaborative Health Education & Research Centre, Bendigo Health, following consultation with local stakeholders and assisted by an advisory committee. It has been updated to include new services that are currently available as at November 2013. 2 Contents Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (ACCHO) ............................................................................. 4 Aged Care Assessment Service (ACAS) ....................................................................................................................... 5 Aged Persons Mental Health Service - Community Team .......................................................................................... 7 Alzheimer’s Australia Vic ............................................................................................................................................ -

Murray Goldfields Western

o! Long Lake Lake Boga WINLATON - Ultima WINLATON NCR NC BLOCK +$+$+$+$ WINLATON - WINLATON - +$ WINLATON Sea Lake WINLATON NCR NCR NE BLOCK Lake Kelly Mystic Park Racecourse Lake Second Marsh BAEL BAEL Koondrook - BLOCK 6 BARAPA BARAPA Berriwillock - LODDON RIVER Duck Lake Middle Lake Little Marsh KORRAK KORRAK Lalbert - BLW KORRAK Lake Bael Reedy Lake KORRAK NCR BAEL Bael BAEL - BARAPA BARAPA KERANG - BLW BLOCK 23 KERANG WR - KERANG +$ Little Lake WHITES LANE +$ +$ Bael Bael TEAL POINT - Culgoa BLW-MCDONALD Kerang SWAMP Fosters Swamp Dry Lake Lake Murphy Tragowel Swamp +$ Cohuna KERANG - MACORNA NORTH +$ KERANG SOUTH - MACORNA NORTH BLW-TRAGOWEL - BLW JOHNSON BLW TRAGOWEL +$ - BLW JOHNSON Towaninny SWAMP NCR BLOCK 1 SWAMP WR BLOCK 1 +$ SWAMP NCR SWAMP WR BLOCK 2 Quambatook Tragowel Nullawil Lake Meran APPIN SOUTH - Lake Meran LODDON VALLEY +$ HWY (CFA) MACORNA NORTH - ROWLANDS - +$ HIRD SWAMP WR ROWLANDS BLW FLANNERYS NCR +$+$ ROWLANDS - Leitchville ROWLANDS - BLW+$+$+$+$ BLWFLANNERYSNCR FLANNERYS NCR YORTA YORTA - KOW SWAMP YORTA YORTA +$+$ - KOW SWAMP YORTA YORT+$A - KOW SWAM+$P Gunbower M u r ra y V a lle y H w y Birchip Torrumbarry E Pyramid Hill y ROSLYNMEAD w H NCR - NTH b b CENTRE WEST o +$ C o! Wycheproof TERRICK TERRICK TTNP - CREEK NP - DAVIES STH WEST BLOCK 473 BOORT - +$ Boort +$ +$ DDW BOORT E DDW - BOORT +$ YANDO RD LAKE LYNDGER Durham Ox Terrick TERRICK TERRICK +$ Terrick RA NP - TORRUMBARRY Echuca BLOCK 493 L WATCHEM - Lake Marmal o Glenloth d SINGLE TREE d E BOORT - WOOLSHED o BOORT - WOOLSHED n RD (CFA) WATCHEM - SWAMP -

Thematic Environmental History Aboriginal History

THEMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY ABORIGINAL HISTORY Prepared for City of Greater Bendigo FINAL REPORT June 2013 Adopted by City of Greater Bendigo Council July 31, 2013 Table of Contents Greater Bendigo’s original inhabitants 2 Introduction 2 Clans and country 2 Aboriginal life on the plains and in the forests 3 Food 4 Water 4 Warmth 5 Shelter 6 Resources of the plains and forests 6 Timber 6 Stone 8 The daily toolkit 11 Interaction between peoples: trade, marriage and warfare 12 British colonisation 12 Impacts of squatting on Aboriginal people 13 Aboriginal people on the goldfields 14 Aboriginal Protectorates 14 Aboriginal Reserves 15 Fighting for Identity 16 Authors/contributors The authors of this history are: Lovell Chen: Emma Hewitt, Dr Conrad Hamann, Anita Brady Dr Robyn Ballinger Dr Colin Pardoe LOVELL CHEN 2013 1 Greater Bendigo’s original inhabitants Introduction An account of the daily lives of the area’s Aboriginal peoples prior to European contact was written during the research for the Greater Bendigo Thematic Environmental History to achieve some understanding of life before European settlement, and to assist with tracing later patterns and changes. The repercussions of colonialism impacted beyond the Greater Bendigo area and it was necessary to extend the account of this area’s Aboriginal peoples to a Victorian context, including to trace movement and resettlement beyond this region. This Aboriginal history was drawn from historical records which include the observations of the first Europeans in the area, who documented what they saw in writing and sketches. Europeans brought their own cultural perceptions, interpretations and understandings to the documentation of Aboriginal life, and the stories recorded were not those of the Aboriginal people themselves. -

![Bendigo [PDF 922KB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4879/bendigo-pdf-922kb-2014879.webp)

Bendigo [PDF 922KB]

Lake Yando Pyramid Hill Murphy Swamp March 2021 N Lake Lyndger Moama Boort MAP OF PROPOSED Little Lake Boort Lake BoortCOMMONWEALTH ELECTORAL DIVISION OF Echuca Woolshed Swamp MITIAMO RD H CA BENDIGO EC U 0 10 km Strathallan Y RD W Prairie H L O Milloo CAMPASPE D D I D M O A RD N Timmering R Korong Vale Y P Rochester Lo d d o n V Wedderburn A Tandarra N L R Greens Lake L E E H Y k HWY ee T Cr R O Corop BENDIGO Kamarooka East N MIDLAND R Elmore Lake Cooper i LODDON v s N H r e W e O r Y y r Glenalbyn S M e Y v i Kurting N R N E Y T W Bridgewater on H Inglewood O Loddon G N I Goornong O D R NICHOLLS e N D N p C E A T MALLEE A L s D H L B I a D M p E E m NICHOLLS R R Derby a Huntly Bagshot N MALLEE C H Arnold Leichardt W Y GREATER BENDIGO H W Marong W Llanelly IMMER A Y HWY Moliagul Newbridge Bendigo M Murphys CIVOR Creek Tarnagulla HW Y Redcastle STRATHBOGIE Stratheldsaye Knowsley Laanecoorie Shelbourne Reservoir Shelbourne Lockwood South Derrinal Dunolly Eddington BENDIGO Bromley Ravenswood Lake Heathcote BENDIGO Eppalock Ravenswood South Argyle C Heathcote South A L D locality boundary E Harcourt R CENTRAL GOLDFIELDS Maldon Cairn Curran Dairy Flat Road Reservoir MOUNT ALEXANDER Redesdale RENEE Tooborac Maryborough PY S N MITCHELL O Castlemaine R Carisbrook HW F T Y W H Moolort Y E Joyces Creek Campbells Chewton R Elphinstone N J Creek Pyalong Tullaroop o y Newstead Reservoir c Strathlea e s Taradale Talbot Benloch locality H Malmsbury MACEDON W boundary Y Caralulup C RANGES re k ek e re Redesdale Junction C o Kyneton Pastoria locality