Android App Development in Android Studio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamza Ahmed Qureshi

HAMZA AHMED QURESHI add 135 Hillcrest Avenue, Mississauga, ON, Canada | tel +1 (647) 522-0048 url hamza1592.github.io | email [email protected] | LinkedIn | Stack Overflow | Github Summary Proficient in writing code in Java, Kotlin, Node.js and other languages as well as practiced in using Amazon Web Service, Firebase and other latest frameworks and libraries Three years of android development experience through development of multiple applications Skilled in writing generic and expandable code and bridging the gap between web and android applications through development of REST APIs Experienced team player and a leader utilizing collaboration, cooperation and leadership skills acquired while working in different environments of startup, industry and entrepreneurship. Technical Skills Languages & Frameworks used: In depth: Java, Android SDK, Node.js, Amazon Web Services, Firebase, JavaScript, JUnit testing, Espresso As a hobby: CodeIgniter, Magento, OpenGL, React Native, Jekyll Platforms: Android, Web, Windows, Linux Software and IDEs: Intellij Idea, Android Studio, Eclipse, Webstorm, Microsoft Visual Studio Databases used: Firebase Realtime Database, Firebase Firestore, MySQL, SQLite, Oracle DB, Redis Version Control: Git, Gitlab, SourceTree, Android Studio version control SDLC: Agile Development, Test Driven Development (TDD), Scrum, Object Oriented Programming Security: OAuth, OAuth2, Kerberos, SSL, Android keystore Design patterns: MVC, MVVM Professional Experience Full stack android developer, teaBOT inc. Feb 2017 – Present Lead the teaBOT kiosk application and build new features for it Enhanced the teaBOT backend Node.js Api and added new endpoints Wrote manageable and scalable code for both static and dynamic views rendering Created static and dynamic functional components from start to end Supported multiple screen sizes including 15inch tablets Directly managed interns working on the Android application Projects: o teaBOT Android Kiosk Application . -

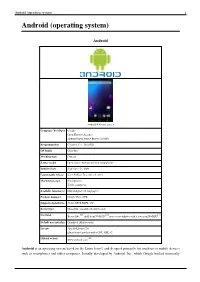

Android (Operating System) 1 Android (Operating System)

Android (operating system) 1 Android (operating system) Android Home screen displayed by Samsung Nexus S with Google running Android 2.3 "Gingerbread" Company / developer Google Inc., Open Handset Alliance [1] Programmed in C (core), C++ (some third-party libraries), Java (UI) Working state Current [2] Source model Free and open source software (3.0 is currently in closed development) Initial release 21 October 2008 Latest stable release Tablets: [3] 3.0.1 (Honeycomb) Phones: [3] 2.3.3 (Gingerbread) / 24 February 2011 [4] Supported platforms ARM, MIPS, Power, x86 Kernel type Monolithic, modified Linux kernel Default user interface Graphical [5] License Apache 2.0, Linux kernel patches are under GPL v2 Official website [www.android.com www.android.com] Android is a software stack for mobile devices that includes an operating system, middleware and key applications.[6] [7] Google Inc. purchased the initial developer of the software, Android Inc., in 2005.[8] Android's mobile operating system is based on a modified version of the Linux kernel. Google and other members of the Open Handset Alliance collaborated on Android's development and release.[9] [10] The Android Open Source Project (AOSP) is tasked with the maintenance and further development of Android.[11] The Android operating system is the world's best-selling Smartphone platform.[12] [13] Android has a large community of developers writing applications ("apps") that extend the functionality of the devices. There are currently over 150,000 apps available for Android.[14] [15] Android Market is the online app store run by Google, though apps can also be downloaded from third-party sites. -

Android Operating System

Software Engineering ISSN: 2229-4007 & ISSN: 2229-4015, Volume 3, Issue 1, 2012, pp.-10-13. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=76 ANDROID OPERATING SYSTEM NIMODIA C. AND DESHMUKH H.R. Babasaheb Naik College of Engineering, Pusad, MS, India. *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected], [email protected] Received: February 21, 2012; Accepted: March 15, 2012 Abstract- Android is a software stack for mobile devices that includes an operating system, middleware and key applications. Android, an open source mobile device platform based on the Linux operating system. It has application Framework,enhanced graphics, integrated web browser, relational database, media support, LibWebCore web browser, wide variety of connectivity and much more applications. Android relies on Linux version 2.6 for core system services such as security, memory management, process management, network stack, and driver model. Architecture of Android consist of Applications. Linux kernel, libraries, application framework, Android Runtime. All applications are written using the Java programming language. Android mobile phone platform is going to be more secure than Apple’s iPhone or any other device in the long run. Keywords- 3G, Dalvik Virtual Machine, EGPRS, LiMo, Open Handset Alliance, SQLite, WCDMA/HSUPA Citation: Nimodia C. and Deshmukh H.R. (2012) Android Operating System. Software Engineering, ISSN: 2229-4007 & ISSN: 2229-4015, Volume 3, Issue 1, pp.-10-13. Copyright: Copyright©2012 Nimodia C. and Deshmukh H.R. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

13 Cool Things You Can Do with Google Chromecast Chromecast

13 Cool Things You Can Do With Google Chromecast We bet you don't even know half of these Google Chromecast is a popular streaming dongle that makes for an easy and affordable way of throwing content from your smartphone, tablet, or computer to your television wirelessly. There’s so much you can do with it than just streaming Netflix, Hulu, Spotify, HBO and more from your mobile device and computer, to your TV. Our guide on How Does Google Chromecast Work explains more about what the device can do. The seemingly simple, ultraportable plug and play device has a few tricks up its sleeve that aren’t immediately apparent. Here’s a roundup of some of the hidden Chromecast tips and tricks you may not know that can make casting more magical. Chromecast Tips and Tricks You Didn’t Know 1. Enable Guest Mode 2. Make presentations 3. Play plenty of games 4. Cast videos using your voice 5. Stream live feeds from security cameras on your TV 6. Watch Amazon Prime Video on your TV 7. Create a casting queue 8. Cast Plex 9. Plug in your headphones 10. Share VR headset view with others 11. Cast on the go 12. Power on your TV 13. Get free movies and other perks Enable Guest Mode If you have guests over at your home, whether you’re hosting a family reunion, or have a party, you can let them cast their favorite music or TV shows onto your TV, without giving out your WiFi password. To do this, go to the Chromecast settings and enable Guest Mode. -

User Manual Introduction

Item No. 8015 User Manual Introduction Congratulations on choosing the Robosapien Blue™, a sophisticated fusion of technology and personality. With a full range of dynamic motion, interactive sensors and a unique personality, Robosapien Blue™ is more than a mechanical companion; he’s a multi-functional, thinking, feeling robot with attitude! Explore Robosapien Blue™ ’s vast array of functions and programs. Mold his behavior any way you like. Be sure to read this manual carefully for a complete understanding of the many features of your new robot buddy. Product Contents: Robosapien Blue™ x1 Infra-red Remote Controller x1 Pick Up Accessory x1 THUMP SWEEP SWEEP THUMP TALK BACKPICK UP LEAN PICK UP HIGH 5 STRIKE 1 STRIKE 1 LEAN THROW WHISTLE THROW BURP SLEEP LISTEN STRIKE 2 STRIKE 2 B U LL P D E O T Z S E R R E S E T P TU E R T N S S N T R E U P T STRIKE 3 R E S E R T A O R STRIKE 3 B A C K S S P T O E O P SELECT RIGHT T LEF SONIC DANCE D EM 2 EXECUTE O O 1 DEM EXECUTE ALL DEMO WAKE UP POWER OFF Robosapien Blue™ Remote Pick Up Controller Accessory For more information visit: www.wowwee.com P. 1 Content Introduction & Contents P.1-2 Battery Details P.3 Robosapien Blue™ Overview P.4 Robosapien Blue™ Operation Overview P.5 Controller Index P.6 RED Commands - Upper Controller P.7 RED Commands - Middle & Lower Controller P.8 GREEN Commands - Upper Controller P.9 GREEN Commands - Middle & Lower Controller P.10 ORANGE Commands - Upper Controller P.11 ORANGE Commands - Middle & Lower Controller P.12 Programming Mode - Touch Sensors P.13 Programming Mode - Sonic Sensor P.14 Programming Mode - Master Command P.15 Troubleshooting Guide P.16 Warranty P.17 App Functionality P.19 P. -

Google Apps: an Introduction to Picasa

[Not for Circulation] Google Apps: An Introduction to Picasa This document provides an introduction to using Picasa, a free application provided by Google. With Picasa, users are able to add, organize, edit, and share their personal photos, utilizing 1 GB of free space. In order to use Picasa, users need to create a Google Account. Creating a Google Account To create a Google Account, 1. Go to http://www.google.com/. 2. At the top of the screen, select “Gmail”. 3. On the Gmail homepage, click on the right of the screen on the button that is labeled “Create an account”. 4. In order to create an account, you will be asked to fill out information, including choosing a Login name which will serve as your [email protected], as well as a password. After completing all the information, click “I accept. Create my account.” at the bottom of the page. 5. After you successfully fill out all required information, your account will be created. Click on the “Show me my account” button which will direct you to your Gmail homepage. Downloading Picasa To download Picasa, go http://picasa.google.com. 1. Select Download Picasa. 2. Select Save File. Information Technology Services, UIS 1 [Not for Circulation] 3. Click on the downloaded file, and select Run. 4. Follow the installation procedures to complete the installation of Picasa on your computer. When finished, you will be directed to a new screen. Click Get Started with Picasa Web Albums. Importing Pictures Photos can be uploaded into Picasa a variety of ways, all of them very simple to use. -

Android (Operating System) 1 Android (Operating System)

Android (operating system) 1 Android (operating system) Android Android 4.4 home screen Company / developer Google Open Handset Alliance Android Open Source Project (AOSP) Programmed in C (core), C++, Java (UI) OS family Unix-like Working state Current Source model Open source with proprietary components Initial release September 23, 2008 Latest stable release 4.4.2 KitKat / December 9, 2013 Marketing target Smartphones Tablet computers Available language(s) Multi-lingual (46 languages) Package manager Google Play, APK Supported platforms 32-bit ARM, MIPS, x86 Kernel type Monolithic (modified Linux kernel) [1] [2] [3] Userland Bionic libc, shell from NetBSD, native core utilities with a few from NetBSD Default user interface Graphical (Multi-touch) License Apache License 2.0 Linux kernel patches under GNU GPL v2 [4] Official website www.android.com Android is an operating system based on the Linux kernel, and designed primarily for touchscreen mobile devices such as smartphones and tablet computers. Initially developed by Android, Inc., which Google backed financially Android (operating system) 2 and later bought in 2005, Android was unveiled in 2007 along with the founding of the Open Handset Alliance: a consortium of hardware, software, and telecommunication companies devoted to advancing open standards for mobile devices. The first publicly available smartphone running Android, the HTC Dream, was released on October 22, 2008. The user interface of Android is based on direct manipulation, using touch inputs that loosely correspond to real-world actions, like swiping, tapping, pinching and reverse pinching to manipulate on-screen objects. Internal hardware such as accelerometers, gyroscopes and proximity sensors are used by some applications to respond to additional user actions, for example adjusting the screen from portrait to landscape depending on how the device is oriented. -

Maksym Govorischev

Maksym Govorischev E-mail : [email protected] Skills & Tools Programming and Scripting Languages: Java, Groovy, Scala Programming metodologies: OOP, Functional Programming, Design Patterns, REST Technologies and Frameworks: - Application development: Java SE 8 Spring Framework(Core, MVC, Security, Integration) Java EE 6 JPA/Hibernate - Database development: SQL NoSQL solutions - MongoDB, OrientDB, Cassandra - Frontent development: HTML, CSS (basic) Javascript Frameworks: JQuery, Knockout - Build tools: Gradle Maven Ant - Version Control Systems: Git SVN Project Experience Project: JUL, 2016 - OCT, 2016 Project Role: Senior Developer Description: Project's aim was essentially to create a microservices architecture blueprint, incorporating business agnostic integrations with various third-party Ecommerce, Social, IoT and Machine Learning solutions, orchestrating them into single coherent system and allowing a particular business to quickly build rich online experience with discussions, IoT support and Maksym Govorischev 1 recommendations engine, by just adding business specific services layer on top of accelerator. Participation: Played a Key developer role to implement integration with IoT platform (AWS IoT) and recommendation engine (Prediction IO), by building corresponding integration microservices. Tools: Maven, GitLab, SonarQube, Jenkins, Docker, PostgreSQL, Cassandra, Prediction IO Technologies: Java 8, Scala, Spring Boot, REST, Netflix Zuul, Netflix Eureka, Hystrix Project: Office Space Management Portal DEC, 2015 - FEB, 2016 -

History and Evolution of the Android OS

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector CHAPTER 1 History and Evolution of the Android OS I’m going to destroy Android, because it’s a stolen product. I’m willing to go thermonuclear war on this. —Steve Jobs, Apple Inc. Android, Inc. started with a clear mission by its creators. According to Andy Rubin, one of Android’s founders, Android Inc. was to develop “smarter mobile devices that are more aware of its owner’s location and preferences.” Rubin further stated, “If people are smart, that information starts getting aggregated into consumer products.” The year was 2003 and the location was Palo Alto, California. This was the year Android was born. While Android, Inc. started operations secretly, today the entire world knows about Android. It is no secret that Android is an operating system (OS) for modern day smartphones, tablets, and soon-to-be laptops, but what exactly does that mean? What did Android used to look like? How has it gotten where it is today? All of these questions and more will be answered in this brief chapter. Origins Android first appeared on the technology radar in 2005 when Google, the multibillion- dollar technology company, purchased Android, Inc. At the time, not much was known about Android and what Google intended on doing with it. Information was sparse until 2007, when Google announced the world’s first truly open platform for mobile devices. The First Distribution of Android On November 5, 2007, a press release from the Open Handset Alliance set the stage for the future of the Android platform. -

Tutorial: Setup for Android Development

Tutorial: Setup for Android Development Adam C. Champion, Ph.D. CSE 5236: Mobile Application Development Autumn 2019 Based on material from C. Horstmann [1], J. Bloch [2], C. Collins et al. [4], M.L. Sichitiu (NCSU), V. Janjic (Imperial College London), CSE 2221 (OSU), and other sources 1 Outline • Getting Started • Android Programming 2 Getting Started (1) • Need to install Java Development Kit (JDK) (not Java Runtime Environment (JRE)) to write Android programs • Download JDK for your OS: https://adoptopenjdk.net/ * • Alternatively, for OS X, Linux: – OS X: Install Homebrew (http://brew.sh) via Terminal, – Linux: • Debian/Ubuntu: sudo apt install openjdk-8-jdk • Fedora/CentOS: yum install java-1.8.0-openjdk-devel * Why OpenJDK 8? Oracle changed Java licensing (commercial use costs $$$); Android SDK tools require version 8. 3 Getting Started (2) • After installing JDK, download Android SDK from http://developer.android.com • Simplest: download and install Android Studio bundle (including Android SDK) for your OS • Alternative: brew cask install android- studio (Mac/Homebrew) • We’ll use Android Studio with SDK included (easiest) 4 Install! 5 Getting Started (3) • Install Android Studio directly (Windows, Mac); unzip to directory android-studio, then run ./android-studio/bin/studio64.sh (Linux) 6 Getting Started (4) • Strongly recommend testing Android Studio menu → Preferences… or with real Android device File → Settings… – Android emulator: slow – Faster emulator: Genymotion [14], [15] – Install USB drivers for your Android device! • Bring up Android SDK Manager – Install Android 5.x–8.x APIs, Google support repository, Google Play services – Don’t worry about non-x86 Now you’re ready for Android development! system images 7 Outline • Getting Started • Android Programming 8 Introduction to Android • Popular mobile device Mobile OS Market Share OS: 73% of worldwide Worldwide (Jul. -

SDK Developer Reference Manual

SDK Developer Reference Manual Version 1.0 13 Aout 2019 Mobiyo Pôle Produit 94 Rue de Villiers 92832 Levallois Perret Cedex – France SAS au capital de 2 486 196€, RCS Paris 824 638 209, N° TVA Intracommunautaire : FR61 824 638 209, Code APE : 6201Z i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents Overview ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 What is the Mobiyo SDK . .1 What is an SDK ? �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������1 What is a REST Web Service? �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������1 Who may use this SDK? ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������2 Knowledge and skills . 2 How to read this documentation? . 2 Starting Guide �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 3 Basic Concept ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������3 Requests . 3 Responses ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 Character encoding ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5 Dates . 5 Available formats ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Picasa Getting Started Guide

Picasa Getting Started Guide Picasa is free photo management software from Google that helps you find, edit and share your photos in seconds. We recommend that you print out this brief overview of Picasa's main features and consult it as you use the program for the first time to learn about new features quickly. Organize Once you start Picasa, it scans your hard drive to find and automatically organize all your photos. Picasa finds the following photo and movie file types: • Photo file types: JPG, GIF, TIF, PSD, PNG, BMP, RAW (including NEF and CRW). GIF and PNG files are not scanned by default, but you can enable them in the Tools > Options dialog. • Movie file types: MPG, AVI, ASF, WMV, MOV. If you are upgrading from an older version of Picasa, you will likely want to keep your existing database, which contains any organization and photo edits you have made. To transfer all this information, simply install Picasa without uninstalling Picasa already on your computer. On your first launch of Picasa you will be prompted to transfer your existing database. After this process is complete, you can uninstall Picasa. Library view Picasa automatically organizes all your photo and movie files into collections of folders inside its main Library view. Layout of main Library screen: Picasa Getting Started Guide Page 1 of 9 Folder list The left-hand list in Picasa's Library view shows all the folders containing photos on your computer and all the albums you've created in Picasa. These folders and albums are grouped into collections that are described in the next section.