Advances in De Novo Drug Design: from Conventional to Machine Learning Methods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ion Channels in Drug Discovery

Department of Physiology and Pharmacology Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Thesis for doctoral degree (Ph.D.) 2008 Thesis for doctoral degree (Ph.D.) 2008 Ion Channels in Drug Discovery - focus on biological assays Ion Channels in Drug Discovery - focus on biological assays Kim Dekermendjian Ion Channels in Drug Discovery - focus on biological - focus on in Drug assays Channels Discovery Ion Kim Dekermendjian Kim Dekermendjian Stockholm 2008 Department of Physiology and Pharmacology Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Ion Channels in Drug Discovery - focus on biological assays Kim Dekermendjian Stockholm 2008 Main Supervisor: Bertil B Fredholm, Professor Department of Physiology and Pharmacology Karolinska Institutet. Co-Supervisor: Olof Larsson, PhD Associated Director Department of Molecular Pharmacology, Astrazeneca R&D Södertälje. Opponent: Bjarke Ebert, Adjunct Professor Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. and Department of Electrophysiology, H. Lundbeck A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark. Examination board: Ole Kiehn, Professor Department of Neurovetenskap, Karolinska Institutet. Bryndis Birnir, PhD Docent Department of Clinical Sciences, Lund University. Bo Rydqvist, Professor Department of Physiology and Pharmacology Karolinska Institutet. All previously published papers were reproduced with permission from the publisher. Front page (a) Side view of the GABA-A model; the trans membrane domain (TMD) (bottom) spans through the lipid membrane (32 Å) and partly on the extracellular side (12 Å), while the ligand binding domain (LBD) (top) is completely extracellular (60 Å). (b) The LBD viewed from the extracellular side (diameter of 80 Å). (c) The TMD viewed from the extracellular side. Arrows and ribbons (which correspond to ȕ-strands and Į- helices, respectively) are coloured according to position in each individual subunit sequence, as well as in the TM4 of each subunit which is not bonded to the rest of the model (with permission from Campagna-Slater and Weaver, 2007 Copyright © 2006 Elsevier Inc.). -

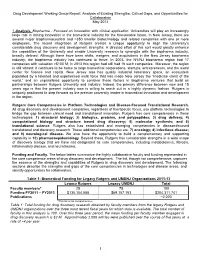

1 Drug Development Working Group Report: Analysis of Existing

Drug Development Working Group Report: Analysis of Existing Strengths, Critical Gaps, and Opportunities for Collaboration May 2014 1. Analysis. Biopharma - Focused on innovation with clinical application. Universities will play an increasingly large role in driving innovation in the biomedical industry for the foreseeable future. In New Jersey, there are several major biopharmaceutical and >350 smaller biotechnology and related companies with one or more employees. The recent integration of Rutgers creates a unique opportunity to align the University’s considerable drug discovery and development strengths. A directed effort of this sort would greatly enhance the capabilities of the University and enable University research to synergize with the biopharma industry, broadly defined. Although there have been shifts, mergers, and acquisitions in the New Jersey biopharma industry, the biopharma industry has continued to thrive. In 2003, the NY/NJ biopharma region had 17 companies with valuation >$100 M; in 2013 this region had still had 16 such companies. Moreover, the region is still vibrant: it continues to be home to large biomedical corporations, startups, entrepreneurs, and the world center for finance and capital. New Jersey also has quality industrial laboratory space, an ecosystem populated by a talented and experienced work force that has made New Jersey the “medicine chest of the world,” and an unparalleled opportunity to combine these factors in biopharma ventures that build on partnerships between Rutgers University and industry. Indeed, the primary difference between now and 15 years ago is that the present industry now is willing to reach out in a highly dynamic fashion. Rutgers is uniquely positioned to step forward as the premier university leader in biomedical innovation and development in the region. -

Drug Design Project Tips

Drug Design Project Information and Tips CHEM 162B (2012) Part of your grade in Drug Design courses will come from a development of a “Drug Design Project”. Students who have taken Chem162A will be able to continue their project development; students who have not taken Chem 162A can pick one of the projects developed in past and take it further. Students will present their projects during the annual Drug Design Poster Event. Students taking Chem 162 during the Winter 2011 will be able accomplish three important milestones toward completing the Project. Part of your grade will be based on your success in completing these milestones. The milestones that you are expected to complete during the Spring 2012 are: 1) Characterize a validated protein/nucleic acid target for the disease that you are working on. If the target is an enzyme, describe in detail the reaction it catalyzes. If the target is not an enzyme, describe in detail its physiological role and mode of operation 2) Obtain or create a virtual library of possible drug candidates that are expected to bind to this target and carry out virtual screening to identify best binders 3) Describe adsorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and possible toxicity aspects of your drug candidate(s). If appropriate, propose modifications to improve your drug. You are expected to turn in your work on each milestone by the due dates specified; you’ll automatically receive 3 points per each milestone if you submit a significantly developed work by the due date. You will earn extra 5 points if you submit all milestones by the due date. -

Computational Approaches for Drug Design and Discovery: an Overview

Review Article Computational Approaches for Drug Design and Discovery: An Overview Baldi A College of Pharmacy, Dr. Shri R.M.S. Institute of Science & Technology, Bhanpura, Dist. Mandsaur (M.P.), India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The process of drug discovery is very complex and requires an interdisciplinary effort to design Received 12 July 2009 effective and commercially feasible drugs. The objective of drug design is to find a chemical Accepted 21 July 2009 compound that can fit to a specific cavity on a protein target both geometrically and chemically. Available online 04 February 2010 After passing the animal tests and human clinical trials, this compound becomes a drug available Keywords: to patients. The conventional drug design methods include random screening of chemicals Computer-aided drug design found in nature or synthesized in laboratories. The problems with this method are long design Combinatorial chemistry cycle and high cost. Modern approach including structure-based drug design with the help Drug of informatic technologies and computational methods has speeded up the drug discovery Structure-based drug deign process in an efficient manner. Remarkable progress has been made during the past five years in almost all the areas concerned with drug design and discovery. An improved generation of softwares with easy operation and superior computational tools to generate chemically stable and worthy compounds with refinement capability has been developed. These tools can tap into cheminformation to shorten the cycle of drug discovery, and thus make drug discovery more cost-effective. A complete overview of drug discovery process with comparison of conventional approaches of drug discovery is discussed here. -

Visualization of Chemical Space Using Principal Component Analysis

World Applied Sciences Journal 29 (Data Mining and Soft Computing Techniques): 53-59, 2014 ISSN 1818-4952 © IDOSI Publications, 2014 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wasj.2014.29.dmsct.10 Visualization of Chemical Space Using Principal Component Analysis B. Firdaus Begam and J. Satheesh Kumar Department of Computer Applications, School of Computer Science and Engineering, Bharathiar University, Coimbatore, Tamilnadu, India Abstract: Principal component analysis is one of the most widely used multivariate methods to visualize chemical space in new dimension by the chemist for analysing data. In Multivariate data analysis, the relationship between two variables with more number of characteristics can be considered. PCA provides a compact view of variation in chemical data matrix which helps in creating better Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship (QSAR) model. It highlights the dominating pattern in the matrix through principal component and graphical representation. This paper focuses on mathematical aspects of principal components and role of PCA on Maybridge dataset to identify dominating hidden patterns of drug likeness based on Lipinski RO5. Key words: Principal Component Analysis Load p lot Score plot Biplot INTRODUCTION a new model of selected objects and variables with minimal loss of information. It can also be used for Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a multivariate prediction model as PCA acts as exploratory tool for data statistical approach to analyze data in lower dimensional analysis by calculating the variance among the variables space. PCA used vector space transformation technique which are uncorrelated [8]. to view datasets from higher-dimensional space to lower Chemical space (drug space) is defined as dimensional space. PCA is an application of linear algebra number of descriptors calculated for each molecule [2] which was first coined by Karl Pearson during 1901 [1]. -

Recent Advances in Automated Protein Design and Its Future

EXPERT OPINION ON DRUG DISCOVERY 2018, VOL. 13, NO. 7, 587–604 https://doi.org/10.1080/17460441.2018.1465922 REVIEW Recent advances in automated protein design and its future challenges Dani Setiawana, Jeffrey Brenderb and Yang Zhanga,c aDepartment of Computational Medicine and Bioinformatics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; bRadiation Biology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute – NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA; cDepartment of Biological Chemistry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Introduction: Protein function is determined by protein structure which is in turn determined by the Received 25 October 2017 corresponding protein sequence. If the rules that cause a protein to adopt a particular structure are Accepted 13 April 2018 understood, it should be possible to refine or even redefine the function of a protein by working KEYWORDS backwards from the desired structure to the sequence. Automated protein design attempts to calculate Protein design; automated the effects of mutations computationally with the goal of more radical or complex transformations than protein design; ab initio are accessible by experimental techniques. design; scoring function; Areas covered: The authors give a brief overview of the recent methodological advances in computer- protein folding; aided protein design, showing how methodological choices affect final design and how automated conformational search protein design can be used to address problems considered beyond traditional protein engineering, including the creation of novel protein scaffolds for drug development. Also, the authors address specifically the future challenges in the development of automated protein design. Expert opinion: Automated protein design holds potential as a protein engineering technique, parti- cularly in cases where screening by combinatorial mutagenesis is problematic. -

Protein Structure Analysis: Introducing Students to Rational Drug Design

INQUIRY & Protein Structure Analysis: INVESTIGATION Introducing Students to Rational Drug Design • AGNIESZKA SZARECKA, CHRISTOPHER DOBSON ABSTRACT the steps involved in computational drug-design pipelines, a process We describe a series of engaging exercises in which students emulate the process that uses structural data for a specific protein target to rationally that researchers use to efficiently develop new pharmaceutical drugs, that of design the best effector molecule – a drug candidate. rational drug design. The activities are taken from a three- to four-hour Unlike most wet-lab experiments in molecular biology and bio- workshop regularly conducted with first-year college students and presented chemistry, these computational experiments do not require expen- here to take place over three to four class periods. Although targeted at college sive equipment or laboratory setups. The tools we describe here students, these activities may be appropriate at the high school level as well, are predominantly free online resources that are accessible via stan- particularly in an AP Biology course. The exercises introduce students to the dard Internet connection. Locally run software can also be used, topics of bioinformatics and computer modeling, in the context of rational drug design, using free online resources such as databases and computer programs. and we will recommend free and easy-to-install programs, capable Through the process of learning about computational drug design and drug of running on the majority of common platforms. The exercises optimization, students also learn content such as elements of protein structure can easily be divided between pre-lab, in-class, and homework and protein–ligand interactions. -

Exploring Chemical Space

Frontier of Chemistry Exploring Chemical Space Shuli Mao 04/12/2008 Shuli Mao @ Wipf Group Page 1 of 40 4/15/2008 What is chemical space? Chemical space is the space spanned by all possible (i.e. energetically stable) stoichiometrical combinations of electrons and atomic nuclei and topologies (isomers) in molecules and compounds in general. -----wilkipedia Chemical space is defined as the total descriptor space that encompasses all the small carbon-based molecules that could in principle be created. (Descriptors: molecular mass, liphophilicity and topological features, etc.) -----Dobson, C. M. Chemical space and biology Nature 2004, 432, 824. Shuli Mao @ Wipf Group Page 2 of 40 4/15/2008 Why we need to explore chemical space? The estimated number of small carbon-based compounds is on the order of 1060. However, only a minute fraction of this chemical space has been explored. Given the vastness of chemical space, we need to explore chemical space efficiently to find biologically relevant chemical space (space in which biologically active compounds reside). Dobson, C. M. Chemical space and biology Nature 2004, 432, 824. • To understand biological systems especially in unknown area • To develop potential drugs From 1994 to 2001, only 22 drugs that modulate new targets were approved. So far, less than 500 human proteins have been targeted by current drugs, which is a small portion of human proteins. Lipinski, C; Hopkins, A. Navigating chemical space for biology and medicine Nature 2004, 432, 855. Shuli Mao @ Wipf Group Page 3 of 40 4/15/2008 How to explore chemical space? Three approaches: (A) Target-Oriented Synthesis (B) Focused Synthesis (Medicinal Chemistry/ Combinatorial Chemistry) (C) Diversity-Oriented Synthesis Burke, M. -

Exploring Non-Covalent Interactions Between Drug-Like Molecules and the Protein Acetylcholinesterase

Exploring non-covalent interactions between drug-like molecules and the protein acetylcholinesterase Lotta Berg Doctoral Thesis, 2017 Department of Chemistry Umeå University, Sweden This work is protected by the Swedish Copyright Legislation (Act 1960:729) ISBN: 978-91-7601-644-2 Elektronisk version tillgänglig på http://umu.diva-portal.org/ Printed by: VMC-KBC Umeå Umeå, Sweden, 2017 “Life is a relationship between molecules, not a property of any one molecule” Emile Zuckerkandl and Linus Pauling 1962 i Table of contents Abstract vi Sammanfattning vii Papers covered in the thesis viii List of abbreviations x 1. Introduction 1 1.1. Drug discovery 1 1.2. The importance of non-covalent interactions 1 1.3. Fundamental forces of non-covalent interactions 2 1.4. Classes of non-covalent interactions 3 1.5. Hydrogen bonds 3 1.5.1. Definition of the hydrogen bond 3 1.5.2. Classical and non-classical hydrogen bonds 4 1.5.3. CH∙∙∙Y hydrogen bonds 5 1.6. Interactions between aromatic rings 6 1.7. Thermodynamics of binding 7 1.8. The essential enzyme acetylcholinesterase 8 1.8.1. The relevance of research focused on AChE 8 1.8.2. The structure of AChE 9 1.8.3. AChE in drug discovery 10 2. Scope of the thesis 12 3. Background to techniques and methods 13 3.1. Structure determination by X-ray crystallography 13 3.1.1. The significance of crystal structures of proteins 13 3.1.2. Data collection and structure refinement 13 3.1.3. Electron density maps 14 3.1.4. -

Clinical Pharmacology of Antiмcancer Agents

A CLINI CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OF NTI- C ANTI-CANCER AGENTS C AL PHARMA AN Cristiana Sessa, Luca Gianni, Marina Garassino, Henk van Halteren www.esmo.org C ER A This is a user-friendly handbook, designed for young GENTS medical oncologists, where they can access the essential C information they need for providing the treatment which could OLOGY OF have the highest chance of being effective and tolerable. By finding out more about pharmacology from this handbook, young medical oncologists will be better able to assess the different options available and become more knowledgeable in the evaluation of new treatments. ESMO ESMO Handbook Series European Society for Medical Oncology CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OF Via Luigi Taddei 4, 6962 Viganello-Lugano, Switzerland Handbook Series ANTI-CANCER AGENTS Cristiana Sessa, Luca Gianni, Marina Garassino, Henk van Halteren ESMO Press · ISBN 978-88-906359-1-5 ISBN 978-88-906359-1-5 www.esmo.org 9 788890 635915 ESMO Handbook Series handbook_print_NEW.indd 1 30/08/12 16:32 ESMO HANDBOOK OF CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OF ANTI-CANCER AGENTS CM15 ESMO Handbook 2012 V14.indd1 1 2/9/12 17:17:35 ESMO HANDBOOK OF CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OF ANTI-CANCER AGENTS Edited by Cristiana Sessa Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland, Bellinzona, Switzerland; Ospedale San Raffaele, IRCCS, Unit of New Drugs and Innovative Therapies, Department of Medical Oncology, Milan, Italy Luca Gianni Ospedale San Raffaele, IRCCS, Unit of New Drugs and Innovative Therapies, Department of Medical Oncology, Milan, Italy Marina Garassino Oncology Department, Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, Italy Henk van Halteren Department of Internal Medicine, Gelderse Vallei Hospital, Ede, The Netherlands ESMO Press CM15 ESMO Handbook 2012 V14.indd3 3 2/9/12 17:17:35 First published in 2012 by ESMO Press © 2012 European Society for Medical Oncology All rights reserved. -

Glossary of Terms Used in Photochemistry, 3Rd Edition (IUPAC

Pure Appl. Chem., Vol. 79, No. 3, pp. 293–465, 2007. doi:10.1351/pac200779030293 © 2007 IUPAC INTERNATIONAL UNION OF PURE AND APPLIED CHEMISTRY ORGANIC AND BIOMOLECULAR CHEMISTRY DIVISION* SUBCOMMITTEE ON PHOTOCHEMISTRY GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN PHOTOCHEMISTRY 3rd EDITION (IUPAC Recommendations 2006) Prepared for publication by S. E. BRASLAVSKY‡ Max-Planck-Institut für Bioanorganische Chemie, Postfach 10 13 65, 45413 Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany *Membership of the Organic and Biomolecular Chemistry Division Committee during the preparation of this re- port (2003–2006) was as follows: President: T. T. Tidwell (1998–2003), M. Isobe (2002–2005); Vice President: D. StC. Black (1996–2003), V. T. Ivanov (1996–2005); Secretary: G. M. Blackburn (2002–2005); Past President: T. Norin (1996–2003), T. T. Tidwell (1998–2005) (initial date indicates first time elected as Division member). The list of the other Division members can be found in <http://www.iupac.org/divisions/III/members.html>. Membership of the Subcommittee on Photochemistry (2003–2005) was as follows: S. E. Braslavsky (Germany, Chairperson), A. U. Acuña (Spain), T. D. Z. Atvars (Brazil), C. Bohne (Canada), R. Bonneau (France), A. M. Braun (Germany), A. Chibisov (Russia), K. Ghiggino (Australia), A. Kutateladze (USA), H. Lemmetyinen (Finland), M. Litter (Argentina), H. Miyasaka (Japan), M. Olivucci (Italy), D. Phillips (UK), R. O. Rahn (USA), E. San Román (Argentina), N. Serpone (Canada), M. Terazima (Japan). Contributors to the 3rd edition were: A. U. Acuña, W. Adam, F. Amat, D. Armesto, T. D. Z. Atvars, A. Bard, E. Bill, L. O. Björn, C. Bohne, J. Bolton, R. Bonneau, H. -

Biological Target and Its Mechanism He Zuan* Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine,Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518000, China

OPEN ACCESS Freely available online Journal of Cell Signaling Editorial Biological Target and Its Mechanism He Zuan* Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine,Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518000, China EDITORIAL NOTE 1. There is no direct change in the biological target, but the binding of the substance stops other endogenous substances (such Biological target is whatsoever within an alive organism to which as triggering hormones) from binding to the target. Contingent some other entity (like an endogenous drug or ligand) is absorbed on the nature of the target, this effect is mentioned as receptor and binds, subsequent in a modification in its function or antagonism, ion channel blockade or enzyme inhibition. behaviour. For examples of mutual biological targets are nucleic acids and proteins. Definition is context dependent, and can refer 2. A conformational change in the target is induced by the stimulus to the biological target of a pharmacologically active drug multiple, which results in a change in target function. This change in function the receptor target of a hormone like insulin, or some other target can mimic the effect of the endogenous substance in which case of an external stimulus. Biological targets are most commonly the effect is referred to as receptor agonism or be the opposite of proteins such as ion channels, enzymes, and receptors. The term the endogenous substance which in the case of receptors is referred "biological target" is regularly used in research of pharmaceutical to as inverse agonism. to describe the nastive protein in body whose activity is altered Conservation Ecology: These biological targets are conserved by a drug subsequent in a specific effect, which may a desirable across species, making pharmaceutical pollution of the therapeutic effect or an unwanted adverse effect.