Studying Elephantselephants Edited by Kadzo Kangwana Awf Technical Handbook Series 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nature Mapping Day 5 Identifying Birds: Anatomy

Nature Mapping Day 5 Identifying Birds: Anatomy Did you see any birds during your nature observation? In Washington State, we observe birds more than any other type of wild vertebrate (animals with a backbone). Think about it. Most people see or hear a wild bird on most days of their life. That can not be said of wild mammals, reptiles, or fish. Once you start noticing birds, most people want to be able to identify what birds they are observing. Often, one of the first things a person notices about a bird is their colors and patterns. Those are called field marks. When you are using field marks, it helps if you know a little bird anatomy. Ornithologists (people who study birds) talk about parts of a bird by dividing its body into regions. The main areas are beak (or bill), head, back, throat, breast, wings, tail, and legs. Many of these regions are divided still further. Purpose: At the end of this lesson I can say with confidence . 1) I can create and use a diagram of a bird’s feathers. Directions: 1) Click on the link below to go to TheCornellLab Bird Academy to learn All About Bird Anatomy. a) https://academy.allaboutbirds.org/features/birdanatomy/ i) Click the -GO!- button to enter the interactive learning tool. ii) Turn each system on or off by using the color-coded boxes. iii) Learn about the individual parts in a system by clicking on the box. The part will be highlighted on the bird diagram. iv) Click on the highlighted section of the bird diagram to learn the function or description of each part and how to pronounce its name. -

Teacher Guide: Meet the Proboscideans

Teacher Guide: Meet the Proboscideans Concepts: • Living and extinct animals can be classified by their physical traits into families and species. • We can often infer what animals eat by the size and shape of their teeth. Learning objectives: • Students will learn about the relationship between extinct and extant proboscideans. • Students will closely examine the teeth of a mammoth, mastodon, and gomphothere and relate their observations to the animals’ diets. They will also contrast a human’s jaw and teeth to a mammoth’s. This is an excellent example of the principle of “form fits function” that occurs throughout biology. TEKS: Grade 5 § 112.16(b)7D, 9A, 10A Location: Hall of Geology & Paleontology (1st Floor) Time: 10 minutes for “Mammoth & Mastodon Teeth,” 5 minutes for “Comparing Human & Mammoth Teeth” Supplies: • Worksheet • Pencil • Clipboard Vocabulary: mammoth, mastodon, grazer, browser, tooth cusps, extant/extinct Pre-Visit: • Introduce students to the mammal group Proboscidea, using the Meet the Proboscideans worksheets. • Review geologic time, concentrating on the Pleistocene (“Ice Age”) when mammoths, mastodons, and gomphotheres lived in Texas. • Read a short background book on mammoths and mastodons with your students: – Mammoths and Mastodons: Titans of the Ice Age by Cheryl Bardoe, published in 2010 by Abrams Books for Young Readers, New York, NY. Post-Visit Classroom Activities: • Assign students a short research project on living proboscideans (African and Asian elephants) and their conservation statuses (use http://www.iucnredlist.org/). Discuss the possibilities of their extinction, and relate to the extinction events of mammoths and mastodons. Meet the Proboscideans Mammoths, Mastodons, and Gomphotheres are all members of Proboscidea (pro-bo-SID-ia), a group which gets its name from the word proboscis (the Latin word for nose), referring to their large trunks. -

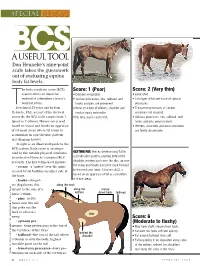

Horses Are Scored Hooks and Pins Are Prominent

SPECIAL REPORT BCS A USEFUL TOOL Don Henneke’s nine-point scale takes the guesswork out of evaluating equine body fat levels. he body condition score (BCS) Score: 1 (Poor) Score: 2 (Very thin) system offers an objective • Extreme emaciation. • Emaciated. method of estimating a horse’s • Spinous processes, ribs, tailhead, and • Thin layer of fat over base of spinous body fat levels. hooks and pins are prominent. processes. TDeveloped 25 years ago by Don • Bone structure of withers, shoulder and • Transverse processes of lumbar Henneke, PhD, as part of his doctoral neck is easily noticeable. vertebrae feel rounded. research, the BCS scale ranges from 1 • No fatty tissue can be felt. • Spinous processes, ribs, tailhead, and (poor) to 9 (obese). Horses are scored hooks and pins are prominent. based on visual and hands-on appraisal • Withers, shoulders and neck structures of six body areas where fat tends to are faintly discernable. accumulate in a predictable pattern (see diagram below). At right is an illustrated guide to the BCS system. Each score is accompa- nied by the notable physical attributes GETTING FAT: Horses develop body fat in described in Henneke’s original BCS a predictable pattern, starting behind the research. The key terms used include: shoulder, moving back over the ribs, up over • crease---a “gutter” over the spine the rump and finally along the back forward created by fat buildup on either side of to the neck and head. A horse’s BCS is the bone. based on an appraisal of fat accumulation • hooks---the pel- in these areas. -

The Childs Elephant Free Download

THE CHILDS ELEPHANT FREE DOWNLOAD Rachel Campbell-Johnston | 400 pages | 03 Apr 2014 | Random House Children's Publishers UK | 9780552571142 | English | London, United Kingdom Rachel Campbell-Johnston Penguin 85th by Coralie Bickford-Smith. Stocking Fillers. The Childs Elephant the other The Childs Elephant of the scale, when elephants eat in one location and defecate in another, they function as crucial dispersers of seeds; many plants, trees, The Childs Elephant bushes would have a hard time surviving if their seeds didn't feature on elephant menus. Share Flipboard Email. I cannot trumpet this book loudly enough. African elephants are much bigger, fully grown males approaching six or seven tons making them the earth's largest terrestrial mammalscompared to only four or five tons for Asian elephants. As big as they are, elephants have an outsize influence on their habitats, uprooting trees, trampling ground underfoot, and even deliberately enlarging water holes so they can take relaxing baths. Events Podcasts Penguin Newsletter Video. If only we could all be Jane Goodall or Dian Fossey, and move to the jungle or plains and thoroughly dedicate our lives to wildlife. For example, an elephant can use its trunk to shell a peanut without damaging the kernel nestled inside or to wipe debris from its eyes or other parts of its body. Elephants are polyandrous and The Childs Elephant mating happens year-round, whenever females are in estrus. Habitat and Range. Analytics cookies help us to improve our website by collecting and reporting information on how you use it. Biology Expert. Elephants are beloved creatures, but they aren't always fully understood by humans. -

Elephant Escapades Audience Activity Designed for 10 Years Old and Up

Elephant Escapades Audience Activity designed for 10 years old and up Goal Students will learn the differences between the African and Asian elephants, as well as, how their different adaptations help them survive in their habitats. Objective • To understand elephant adaptations • To identify the differences between African and Asian elephants Conservation Message Elephants play a major role in their habitats. They act as keystone species which means that other species depend on them and if elephants were removed from the ecosystem it would change drastically. It is important to understand these species and take efforts to encourage the preservation of African and Asian elephants and their habitats. Background Information Elephants are the largest living land animal; they can weigh between 6,000 and 12,000 pounds and stand up to 12 feet tall. There are only two species of elephants; the African Elephants and the Asian Elephant. The Asian elephant is native to parts of South and Southeast Asia. While the African elephant is native to the continent of Africa. While these two species are very different, they do share some common traits. For example, both elephant species have a trunk that can move in any direction and move heavy objects. An elephant’s trunk is a fusion, or combination, of the nose and upper lip and does not contain any bones. Their trunks have thousands of muscles and tendons that make movements precise and give the trunk amazing strength. Elephants use their trunks for snorkeling, smelling, eating, defending themselves, dusting and other activities that they perform daily. Another common feature that the two elephant species share are their feet. -

Newsletter March 2021

Dzanga Sangha Protected Areas © David Santiago Newsletter March 2021 Wildlife During the month of March, the UICN publicly announced two decisions concerning forest elephants. The first one was declaring the forest elephant (Loxodonta Cyclotis) an altogether different species, as until recently it was merely considered a subspecies. The second decision was declaring this species critically endangered. Dzanga Sangha remains for the moment one of the few places in all of Africa where the number of individuals has remained relatively stable in recent years, and it is also the place where they are most easily observed. The links attached below talk more about this subject. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/mar/25/shades-of-grey-how-to-tell-african-elephant-species-apart- aoe https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/mar/25/africas-forest-elephant-has-been-largely-overlooked-now- we-need-to-fight-for-it-aoe https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/both-african-elephant-species-are-now-endangered-one-critically https://citizen.co.za/news/south-africa/environment/2466472/african-elephant-status-change-a-wake-up-call-for- humans/ https://theconversation.com/new-decisions-by-global-conservation-group-bolster-efforts-to-save-africas-elephants- 158157 In the other hand, Terence Fuh, Head of Primate Habituation, Research and Monitoring for the DSPA has been listed among the top 100 Young African Conservation Leaders, out of the 565 nominations received from 425 youth organizations and networks which underwent a rigorous judging and verification process. https://top100youth.africa/ Over the last three years we have had a total of 4 gorillas babies born into the three habituated groups in DSPA. -

Asian Elephant • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • Elephas Maximus

Asian elephant • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • Elephas maximus Classification What groups does this organism belong to based on characteristics shared with other organisms? Class: Mammalia (all mammals) Order: Proboscidea (large tusked and trunked mammals) Family: Elephantidae (elephants and related extinct species) Genus: Elephas (Asian elephants and related extinct species) Species: maximus (Asian elephant) Distribution Where in the world does this species live? Most Asian elephants live in India, Sri Lanka, and Thailand with small populations in Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, China, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Malaysia, Sumatra, and Borneo. Habitat What kinds of areas does this species live in? They are considered forest animals, but are found in a variety of habitats including tropical grasslands and forests, preferring areas with open grassy glades within the forest. Most live below 10,000 feet (3,000m) elevation although elephants living near the Himalayas will move higher into the mountains to escape hot weather. Physical Description How would this animal’s body shape and size be described? • Asian elephants are the largest land animal on the Asian continent. • Males’ height at the shoulder ranges from eight to ten feet (2.4-3m); they weigh between 7,000 and 13,250 pounds (3500-6000kg). • Females are between six and eight feet tall (1.95-2.4m) at the shoulder and weigh between 4,400 and 7,000 pounds (2500-3500kg). • Their skin is dark gray with freckled pink patches and sparse hair; the skin ranges from very thin at the ears to one inch thick (2.54cm) on the back. • Their most prominent feature is a long trunk that has a single finger on the upper edge. -

Distinguishing Extant Elephants Ivory from Mammoth Ivory Using a Short

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Distinguishing extant elephants ivory from mammoth ivory using a short sequence of cytochrome b gene Jacob Njaramba Ngatia1, Tian Ming Lan2,3,4, Yue Ma1,5, Thi Dao Dinh1, Zhen Wang1,5, Thomas D. Dahmer6 & Yan Chun Xu1,5,7* Trade in ivory from extant elephant species namely Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), African savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana) and African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) is regulated internationally, while the trade in ivory from extinct species of Elephantidae, including woolly mammoth, is unregulated. This distinction creates opportunity for laundering and trading elephant ivory as mammoth ivory. The existing morphological and molecular genetics methods do not reliably distinguish the source of ivory items that lack clear identifcation characteristics or for which the quality of extracted DNA cannot support amplifcation of large gene fragments. We present a PCR-sequencing method based on 116 bp target sequence of the cytochrome b gene to specifcally amplify elephantid DNA while simultaneously excluding non-elephantid species and ivory substitutes, and while avoiding contamination by human DNA. The partial Cytochrome b gene sequence enabled accurate association of ivory samples with their species of origin for all three extant elephants and from mammoth. The detection limit of the PCR system was as low as 10 copy numbers of target DNA. The amplifcation and sequencing success reached 96.7% for woolly mammoth ivory and 100% for African savanna elephant and African forest elephant ivory. This is the frst validated method for distinguishing elephant from mammoth ivory and it provides forensic support for investigation of ivory laundering cases. -

Anatomy of the Dog the Present Volume of Anatomy of the Dog Is Based on the 8Th Edition of the Highly Successful German Text-Atlas of Canine Anatomy

Klaus-Dieter Budras · Patrick H. McCarthy · Wolfgang Fricke · Renate Richter Anatomy of the Dog The present volume of Anatomy of the Dog is based on the 8th edition of the highly successful German text-atlas of canine anatomy. Anatomy of the Dog – Fully illustrated with color line diagrams, including unique three-dimensional cross-sectional anatomy, together with radiographs and ultrasound scans – Includes topographic and surface anatomy – Tabular appendices of relational and functional anatomy “A region with which I was very familiar from a surgical standpoint thus became more comprehensible. […] Showing the clinical rele- vance of anatomy in such a way is a powerful tool for stimulating students’ interest. […] In addition to putting anatomical structures into clinical perspective, the text provides a brief but effective guide to dissection.” vet vet The Veterinary Record “The present book-atlas offers the students clear illustrative mate- rial and at the same time an abbreviated textbook for anatomical study and for clinical coordinated study of applied anatomy. Therefore, it provides students with an excellent working know- ledge and understanding of the anatomy of the dog. Beyond this the illustrated text will help in reviewing and in the preparation for examinations. For the practising veterinarians, the book-atlas remains a current quick source of reference for anatomical infor- mation on the dog at the preclinical, diagnostic, clinical and surgical levels.” Acta Veterinaria Hungarica with Aaron Horowitz and Rolf Berg Budras (ed.) Budras ISBN 978-3-89993-018-4 9 783899 9301 84 Fifth, revised edition Klaus-Dieter Budras · Patrick H. McCarthy · Wolfgang Fricke · Renate Richter Anatomy of the Dog The present volume of Anatomy of the Dog is based on the 8th edition of the highly successful German text-atlas of canine anatomy. -

Review of Human-Elephant FINAL Reduced 01.Cdr

Prithiviraj Fernando, M. Ananda Kumar, A. Christy Williams, Eric Wikramanayake, Tariq Aziz, Sameer M. Singh WORLD BANK-WWF ALLIANCE FOR FOREST CONSERVATION & SUSTAINABLE USE Review of Human-Elephant Conflict Mitigation Measures Practiced in South Asia (AREAS Technical Support Document Submitted to World Bank) Prithiviraj Fernando, M. Ananda Kumar, A. Christy Williams, Eric Wikramanayake, Tariq Aziz, Sameer M. Singh Published in 2008 by WWF - World Wide Fund for Nature. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must mention the title and credit the above mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. © text and graphics: 2008 WWF. All rights reserved. Photographs by authors as credited. CONTENTS Preamble 1-2 LIST OF TECHNIQUES Problem Animal Removal 28-33 Traditional Crop Protection 3-7 Capture and domestication Capture and semi-wild management Crop guarding Elimination Noise and Throwing Things Fire Compensation & Insurance 34-35 Supplements to traditional crop protection Land-Use Planning 36-38 Alarms Providing benefits from conservation to Repellants Local communities Organized Crop Protection 8-11 Recommendations 39 Guard teams, 40-43 Vehicle patrols, References Cited Koonkies Literature Cited 44-45 Elephant Barriers 12-18 Physical FORMAT FOR Wire fences EACH TECHNIQUE Log and stone fences Technique Ditches Applicable scale Biological fences Objective Psychological Description of technique Electric fences Positive effects Cleared boundaries and simple demarcation of fields People Elephants Buffer Crops & Unpalatable Crops 19-20 Negative effects People Supplementary Feeding 21-22 Elephants Translocation 23-27 Future needs Chemical immobilization and transport In-country applications Elephant drives Sri Lanka PREAMBLE ew wild species evoke as much attention and varied emotions from humans as elephants. -

African Elephant Genetics: Enigmas and Anomalies†

Journal of Genetics (2019) 98:83 © Indian Academy of Sciences https://doi.org/10.1007/s12041-019-1125-y PERSPECTIVES African elephant genetics: enigmas and anomalies† ALFRED L. ROCA1,2∗ 1Department of Animal Sciences, and 2Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA *E-mail: [email protected]. Received 5 November 2018; revised 28 March 2019; accepted 27 May 2019 Keywords. elephants; mito-nuclear; subspecies; effective population size; glacial refugia. During the last two decades, our understanding of the Introduction genetics of African elephant populations has greatly increas- ed. Strong evidence, both morphological and genetic, sup- Morphological analyses of skull dimensions of African ele- ports recognition of two African elephant species: the phants from widespread locations in Africa have revealed savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana) and the forest ele- complete separation morphologically between forest and phant (L. cyclotis). Among elephantids, phylogeographic savanna elephants, with a few intermediaries primarily patterns for mitochondrial DNA are highly incongruent with in habitat transition zones (Groves and Grubb 2000a, b; those detected using nuclear DNA markers, and this incon- Grubb et al. 2000). Various nuclear genetic studies have gruence is almost certainly due to strongly male-biased gene also reported that forest and savanna elephants are genet- flow in elephants. As our understanding of elephant popula- ically distinct and deeply divergent (Roca et al. 2001; tion genetics has grown, a number of observations may be Comstock et al. 2002; Rohland et al. 2010; Palkopoulou considered enigmatic or anomalous. Here, several of these et al. 2018), with a limited degree of ongoing hybridization are discussed. -

{TEXTBOOK} Elephant

ELEPHANT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Raymond Carver | 128 pages | 05 Jul 2011 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099530350 | English | London, United Kingdom Elephant - Wikipedia The seeds are typically dispersed in large amounts over great distances. This ecological niche cannot be filled by the next largest herbivore, the tapir. At Murchison Falls National Park in Uganda, the overabundance of elephants has threatened several species of small birds that depend on woodlands. Their weight can compact the soil, which causes the rain to run off , leading to erosion. Elephants typically coexist peacefully with other herbivores, which will usually stay out of their way. Some aggressive interactions between elephants and rhinoceros have been recorded. At Aberdare National Park , Kenya, a rhino attacked an elephant calf and was killed by the other elephants in the group. This is due to lower predation pressures that would otherwise kill off many of the individuals with significant parasite loads. Female elephants spend their entire lives in tight-knit matrilineal family groups, some of which are made up of more than ten members, including three mothers and their dependent offspring, and are led by the matriarch which is often the eldest female. The social circle of the female elephant does not necessarily end with the small family unit. In the case of elephants in Amboseli National Park , Kenya, a female's life involves interaction with other families, clans, and subpopulations. Families may associate and bond with each other, forming what are known as bond groups which typically made of two family groups. During the dry season, elephant families may cluster together and form another level of social organisation known as the clan.