Buffalo Bills PE Gets Ralph Wilson Stadium in Shape for Kickoff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Channellock of Meadville, Pennsylvania • Summer 2009

NEWS FROM CHANNELLOCK OF MEADVILLE, PENNSYLVANIA • SUMMER 2009 NEW #89 RESCUE TOOL GOES ONE BETTER First responders help make this “must have” gear, too. When the flames are hot and the smoke is thick, there’s no time for a firefighter to search for tools. CHANNELLOCK® introduces the all-in-one, second-generation #89 Rescue Tool. Packed with functionality. Small enough to carry. So light, it won’t slow you down. Shear perfection. Now, after more than a year of real-world use by firefighters, police and EMTs, CHANNELLOCK® is introducing the new #89 Rescue Tool. Engineers designed the #89 with a powerful cutting head that delivers extra severing leverage. Its hardened cutting edges are crafted to shear through soft metal and standard battery cables. In addition, the tool has… 1 Narrower jaw that slips into tighter spaces 2 Tapered pry wedge that jimmies doors and windows easier 3 Spanner wrench that snugs/loosens standard hose couplings 4 Gas shut-off valve slot 5 Window punch that easily shatters safety glass See it on the job. This next generation of The Rescue Tool gives CHANNELLOCK® serious credibility among first responders. Check out the #89 Rescue Tool in action.Visit www.theRescueTool.com to watch a demonstration, get complete performance details and order one for yourself. WIN A TRIP TO THE PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME Grand Prize: Witness the 2009 induction ceremony and game. 2009 Inductees: Rod Woodson, Bruce Smith, Bob Hayes, Randall McDaniel, Derrick Thomas and Ralph Wilson Jr. Enter to win and get contest rules at www.theRescueTool.com. -

Johnny Robinson Donates Artifacts to the Hall Momentos to Be Displayed in Special Class of 2019 Exhibit

JOHNNY ROBINSON DONATES ARTIFACTS TO THE HALL MOMENTOS TO BE DISPLAYED IN SPECIAL CLASS OF 2019 EXHIBIT June 18, 2019 - CANTON, OHIO - Class of 2019 Enshrinee JOHNNY ROBINSON recently donated several artifacts from his career and life to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Robinson starred for the Kansas City Chiefs, first known as the Dallas Texans, for 12 seasons from 1960-1971. Aligning with its important Mission to “Honor the Heroes of the Game, Preserve its History, Promote its Values & Celebrate Excellence EVERYWHERE,” the Hall’s curatorial team will preserve Robinson’s artifacts for future generations of fans to see. The following are some notable items from Robinson’s collection: • Robinson’s game worn Chiefs jersey • Chiefs helmet worn by Robinson during his career • 1970 NEA-CBS All-Pro Safety Trophy awarded to Robinson after completing the season with a league-leading 10 interceptions DAYS UNTIL NFL’S 100TH SEASON KICKS OFF AT 4 4 ENSHRINEMENT WEEK POWERED BY JOHNSON CONTROLS Great seats are still available for the kickoff of the NFL’s 100th season in Canton, Ohio. Tickets and Packages for the main events of the 2019 Pro Football Hall of Fame Enshrinement Week Powered by Johnson Controls are on sale now. HALL OF FAME GAME - AUG. 1 ENSHRINEMENT CEREMONY - AUG. 3 IMAGINE DRAGONS - AUG. 4 ProFootballHOF.com/Tickets • 2018 PwC Doak Walker Legends Robinson Career Interception Statistics Award which honors former running backs who excelled at the collegiate Year Team Games Number Yards Average level and went on to distinguish 1962 Dallas 14 4 25 6.3 themselves as leaders in their 1963 Kansas City 14 3 41 13.7 communities. -

“Notes & Nuggets” from the Pro

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 09/20/2019 WEEKLY “NOTES & NUGGETS” FROM THE PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME BRONZED BUSTS TRAVEL TO EAGLES FANTENNIAL; BILLY SHAW TOOK PART IN THE HEART OF A HALL OF FAMER PROGRAM; PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME RING OF EXCELLENCE CEREMONIES; MUSEUM DAY; FROM THE ARCHIVES: HALL OF FAMERS ENSHRINED IN THE SAME YEAR FROM THE SAME COLLEGE CANTON, OHIO – The following is a sampling of events, happenings and notes that highlight how the Pro Football Hall of Fame serves its important mission to “Honor the Heroes of the Game, Preserve its History, Promote its Values & Celebrate Excellence EVERYWHERE!” 14 BRONZED BUSTS TRAVEL TO PHILADELPHIA FOR EAGLES FANTENNIAL The Pro Football Hall of Fame sent the Bronzed Busts of 14 Eagles Legends to Philadelphia for the Eagles Fantennial Festival taking place as part of the National Football League’s 100th Season. The busts will be on display during “Eagles Fantennial Festival – Birds. Bites. Beer.” at the Cherry Street Pier on Saturday, Sept. 21 and at Lincoln Financial Field prior to the Eagles game agains the Detroit Lions on Sunday, Sept. 22. The Bronzed Busts to be displayed include: • Bert Bell • Sonny Jurgensen • Norm Van Brocklin • Chuck Bednarik • Tommy McDonald • Steve Van Buren • Bob Brown • Earl “Greasy” Neale • Reggie White • Brian Dawkins • Pete Pihos • Alex Wojciechowicz • Bill Hewitt • Jim Ringo More information on the Eagles Fantennial can be found at https://fanpages.philadelphiaeagles.com/nfl100.html. September 16-19, 2020 A once-in-every- other-lifetime celebration to kick off the NFL’s next century in the city where the league was born. -

Capable Apable

1 BLACK E12 DAILY 10-01-06 MD BD E12 BLACK E12 Sunday, October 1, 2006 B x The Washington Post NFLGameday Compiled By Desmond Bieler, Matt Bonesteel, David Larimer and Christian Swezey Misery Loves Company THE RUNDOWN Arizona (+7) at Atlanta, 1 p.m. We couldn’t pass up a look at the two biggest also-rans in Super Bowl history. Minnesota and Buffalo have combined to lose eight Super Bowls; their inferiority complex must be such that they don’t teach Roman numerals in schools there anymore. The Falcons lead the league in rushing at 225 yards per game, but against the Saints on Monday night, Minnesota at Buffalo Bills Minnesota Vikings they threw the ball eight more times than they ran Buffalo, 1 p.m. it. They abandoned the run partly because they 1991-94 Super losses 1970, ’74, ’75, ’77 were down 20-3 at halftime, but also because the BREAKDOWN Saints were able to keep Michael Vick from getting Marv Levy played three Super Bud Grant, also a to the outside, where he excels. sports at Coe College bosses thinker, quoted ancient 1 31-22 Dallas (-9 ⁄2) at Tennessee, 1 p.m. (WTTG-5) Career record on (Iowa) and earned a philosopher Lao-tse the road for master’s degree from when announcing his Even if Terrell Owens sits after his busy week (and Vikings QB Brad Harvard. retirement. remember, he’s still nursing a broken finger), it’s Johnson, 38. He unlikely Dallas will need him against the foundering has thrown 70 (tie) LB Darryl Talley got into a fight Worst pregame C Scott Anderson had a few drinks a Titans, who rank last in the league in time of touchdown passes with Magic Johnson’s bodyguard a prep week before Super Bowl IX and got possession and giveaways. -

BUFFALO BILLS Team History

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2020-2021 EDITIOn QUARTERBACK JIM KELLY - hall of fame class of 2002 BUFFALO BILLS Team History The Buffalo Bills began their pro football life as the seventh team to be admitted into the new American Football League. The franchise was awarded to Ralph C. Wilson on October 28, 1959. Since that time, the Bills have experienced extended periods of both championship dominance and second-division frustration. The Bills’ first brush with success came in their fourth season in 1963 when they tied for the AFL Eastern division crown but lost to the Boston Patriots in a playoff. In 1964 and 1965 however, they not only won their division but defeated the San Diego Chargers each year for the AFL championship. Head Coach Lou Saban, who was named AFL Coach of the Year each year, departed after the 1965 season. Buffalo lost to the Kansas City Chiefs in the 1966 AFL title game and, in doing so, just missed playing in the first Super Bowl. Then the Bills sank to the depths, winning only 13 games while losing 55 and tying two in the next five seasons. Saban returned in 1972, utilized the Bills’ superstar running back, O. J. Simpson, to the fullest extent and made the Bills competitive once again. That period was highlighted by the 2,003-yard rushing record set by Simpson in 1973. But Saban departed in mid-season 1976 and the Bills again sank into the second division until a new coach, Chuck Knox, brought them an AFC Eastern division title in 1980. -

The Oakland Nomads

University of Central Florida STARS On Sport and Society Public History 4-12-2017 The Oakland Nomads Richard C. Crepeau University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Cultural History Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Sports Management Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Public History at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in On Sport and Society by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Crepeau, Richard C., "The Oakland Nomads" (2017). On Sport and Society. 644. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety/644 SPORT AND SOCIETY FOR H-ARETE – THE OAKLAND NOMADS APRIL 12, 2017 The announcement last week that the Oakland Raiders would, for the second time in its history, leave the city of Oakland came as a shock to no one. The synergistic relationship between the greed of the National Football League and the greed of the principal owner of the Raiders, made such a move an inevitability on the wheel of time. Such “loyalty” to the city of Oakland and its rabid football fans will not go unrewarded. Indeed, both the Raiders owner and the NFL will make out like bandits once again. There were actually some reports last week suggesting that were he alive today, Al Davis, would not have allowed this combined fleecing of Raider fans, the taxpayers of Oakland, and those of Las Vegas. -

The Real Team Players: Legal Ethics, Public Interest, and Professional Sports Subsidies

THE REAL TEAM PLAYERS: LEGAL ETHICS, PUBLIC..., 27 Geo. J. Legal... 27 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 451 Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics Summer, 2014 Current Development 2013-2014 Kukui Claydon a1 Copyright © 2014 by Kukui Claydon THE REAL TEAM PLAYERS: LEGAL ETHICS, PUBLIC INTEREST, AND PROFESSIONAL SPORTS SUBSIDIES INTRODUCTION: FOOTBALL, THE HEART OF AMERICA, AND THE UNDERBELLY OF SUBSIDIZED FINANCING “Football is not a game but a religion, a metaphysical island of fundamental truth in a highly verbalized, disguised society, a throwback of 30,000 generations of anthropological time.” 1 This Note will discuss public subsidies for professional sports stadiums, ethical issues that face attorneys involved in stadium deals, and the need for a more transparent bargaining table where millions of taxpayer dollars are involved. Whether you love it, hate it, or are indifferent, American football encompasses a huge part of modern American cultural identity and passion. 2 Particularly with the rise of television, American football became the country's biggest spectator sport, a cultural pinnacle, and the primary focus of both collegiate athletics and professional sports. Through football, Americans celebrate their local, school, emotional, regional, national, and other identities. Football is an American holiday tradition, a promoter of corporations and universities, a staple of towns, a grower of leaders and promoter of teamwork, a symbol of war, a topic of controversy denounced by some as promoting violence, sexism, and greed, and supported as promoting family values in a religious setting by others. Depending on one's point of view, football may symbolize everything that is right or wrong with American culture and society. -

BUFFALO BILLS Weekly Game Information

BUFFALO BILLS Weekly Game Information REGULAR SEASON GAME #1 BILLS @ PATRIOTS Monday, September 14, 2009 7:00 PM (ET) – Gillette Stadium www.buffalobills.com/media BUFFALO BILLS GAME RELEASE - Week #1 Buffalo Bills (0-0) at New England Patriots (0-0) Monday, September 14 - 7:00 PM ET - Gillette Stadium - Foxborough, MA BILLS FACE PATRIOTS ON KICKOFF WEEKEND BROADCAST INFO The Buffalo Bills will travel to Foxborough, TELEVISION: ESPN / WKBW-TV (Ch. 7 BUF) MA this week to open PLAY-BY-PLAY: Mike Tirico its 2009 regular season COLOR ANALYSTS: Jon Gruden & Ron Jaworski schedule against the New England Patriots on Monday SIDELINE REPORTER: Suzy Kolber PRODUCER: Jay Rothman Night Football with a kickoff slot of 7:00 PM ET. DIRECTOR: Chip Dean With a win this week, the Bills will: BILLS RADIO NETWORK • Win consecutive Kickoff Weekend games for the fi rst FLAGSHIP: Buffalo – 97 Rock (96.9 FM) and The Edge (103.3 time since the 1992 and 1993 seasons FM); Rochester – WHAM (1180 AM); Toronto - FAN (590 AM) • Win its fi rst MNF game since 1999 (10/4/99 at MIA 23-18) PLAY-BY-PLAY: John Murphy (23rd year, 6th as play-by-play) • Clinchits fi rst win against New England since 2003 COLOR ANALYST: Mark Kelso (4th year) SIDELINE REPORTER: Rich Gaenzler (10th year; 1st year as sideline) This week’s game will mark only the second road game on Kickoff Weekend in the past 10 seasons for Buf- falo, which last occurred in 2006 against New England UPCOMING WEEK’S SCHEDULE (9/10/06, L, 17-19). -

A Printable PDF of These Super Bowl Trivia Questions and Answers

1. The Packers have won three Super Bowls, with the most recent coming in 1996. Who was the backup QB for the Packers in that game? a) Ty Detmer b) Don Majkowski c) Jim McMahon d) Mark Brunell 2. Including the three Super Bowl championship Green Bay has won, how many times have they been named NFL champions since Curly Lambeau founded the franchise in 1919? a) 5 b) 9 c) 12 d) 15 3. Three members of the coaching staff for that 1996 championship team from Green Bay went on to coach other teams in the NFL. Which of these guys was not one of them? a) Marty Mornhinweg b) Steve Mariucci c) Mike Holmgren d) Andy Reid 4. Bart Starr was the MVP of the first two Super Bowls that Green Bay won. He was injured in the second game, though, and was unable to play the fourth quarter. What quarterback took his place? (hint: he’s the father of the Bengals’ offensive coordinator) a) Scott Hunter b) Lamar McHan c) Len Dawson d) Zeke Bratkowski 5. The year after they won the Super Bowl Green Bay made the game again but lost it. Who was the MVP of that game? a) Terrell Davis b) Larry Brown c) John Elway d) Shannon Sharpe 6. Desmond Howard was the Super Bowl MVP in 1996 for the Packers. how many other Heisman Trophy winners have also been named Super Bowl MVP? a. 0 b. 1 c. 2 d. 3 7. Mike Tomlin was the youngest coach ever to win a Super Bowl, and if he wins this year he will be the second youngest also. -

Artstor: Digital Technology Inside the Classroom

Spring 2005 A newsletter for members of the Coe College Library Association ARTstor: Digital technology inside the classroom I oe College faculty and students have i ARTstor - Microsoft Internet He E?*t ftem Favorites Toott Heto an additional resource for teaching and conducting research in art history, anthropol• ogy and the humanities. Through Stewart Coe Colege Intranet £j VVebActess ^} Stewart Memorial Ltorary Blackboard Coe Colege Memorial Library's subscription to the ARTstor Digital Library Charter Collection, the Coe community has access to more than 300,000 high-quality digital images of curated collections of art. ATRstor is a non-profit initiative founded in 2004 by The Andrew W. Mellon Founda• tion. It makes the digital images available NewJ £ MOTES UIIM* ARTSTOR solely to non-profit institutions for non• FOR IMAGES commercial, educational use with the goal of enhancing scholarship, teaching, and learning in the arts and associated fields while respect• fT.teri „ Rag, U.S. t ing intellectual property rights. ARTstor's digital library is expected to house approxi• mately half a million images by the summer of 2006. "Our goal is to continually improve the a.jspsmomfl'mage'. t resources available to our faculty, staff and students," said Rich Doyle, director of library The online ARTstor database (shown here) is accessible to the Coe community through the services. He continued, "The ARTstor da• Stewart Memorial Library website. tabase and its software provides faculty and students with access to digital images of nu- merous collections of art from different cul• European prints, medieval architecture, tures, time periods and media. It's an excellent Gothic sculptures, sacred and secular scrolls, classroom and research tool." and ancient mural paintings from Buddhist Thank you CCLA members The Charter Collection is a product of caves in China. -

09FB Guide P163-202 Color.Indd

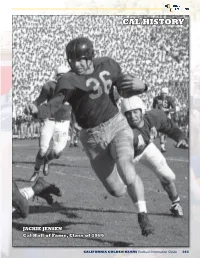

CCALAL HHISTORYISTORY JJACKIEACKIE JJENSENENSEN CCalal HHallall ooff FFame,ame, CClasslass ooff 11986986 CALIFORNIA GOLDEN BEARS FootballFtbllIf Information tiGid Guide 163163 HISTORY OF CAL FOOTBALL, YEAR-BY-YEAR YEAR –––––OVERALL––––– W L T PF PA COACH COACHING SUMMARY 1886 6 2 1 88 35 O.S. Howard COACH (YEARS) W L T PCT 1887 4 0 0 66 12 None O.S. Howard (1886) 6 2 1 .722 1888 6 1 0 104 10 Thomas McClung (1892) 2 1 1 .625 1890 4 0 0 45 4 W.W. Heffelfi nger (1893) 5 1 1 .786 1891 0 1 0 0 36 Charles Gill (1894) 0 1 2 .333 1892 Sp 4 2 0 82 24 Frank Butterworth (1895-96) 9 3 3 .700 1892 Fa 2 1 1 44 34 Thomas McClung Charles Nott (1897) 0 3 2 .200 1893 5 1 1 110 60 W.W. Heffelfi nger Garrett Cochran (1898-99) 15 1 3 .868 1894 0 1 2 12 18 Charles Gill Addison Kelly (1900) 4 2 1 .643 Nibs Price 1895 3 1 1 46 10 Frank Butterworth Frank Simpson (1901) 9 0 1 .950 1896 6 2 2 150 56 James Whipple (1902-03) 14 1 2 .882 1897 0 3 2 8 58 Charles P. Nott James Hooper (1904) 6 1 1 .813 1898 8 0 2 221 5 Garrett Cochran J.W. Knibbs (1905) 4 1 2 .714 1899 7 1 1 142 2 Oscar Taylor (1906-08) 13 10 1 .563 1900 4 2 1 53 7 Addison Kelly James Schaeffer (1909-15) 73 16 8 .794 1901 9 0 1 106 15 Frank Simpson Andy Smith (1916-25) 74 16 7 .799 1902 8 0 0 168 12 James Whipple Nibs Price (1926-30) 27 17 3 .606 1903 6 1 2 128 12 Bill Ingram (1931-34) 27 14 4 .644 1904 6 1 1 75 24 James Hopper Stub Allison (1935-44) 58 42 2 .578 1905 4 1 2 75 12 J.W. -

15 Finalists for Hall of Fame Election

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact January 11, 2006 Joe Horrigan at (330) 456-8207 15 FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION Troy Aikman, Warren Moon, Thurman Thomas, and Reggie White, four first-year eligible candidates, are among the 15 finalists who will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Board of Selectors meets in Detroit, Michigan on Saturday, February 4, 2006. Joining the first-year eligible players as finalists, are nine other modern-era players and a coach and player nominated earlier by the Hall of Fame’s Seniors Committee. The Seniors Committee nominees, announced in August 2005, are John Madden and Rayfield Wright. The other modern-era player finalists include defensive ends L.C. Greenwood and Claude Humphrey; linebackers Harry Carson and Derrick Thomas; offensive linemen Russ Grimm, Bob Kuechenberg and Gary Zimmerman; and wide receivers Michael Irvin and Art Monk. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. Listed alphabetically, the 15 finalists with their positions, teams, and years follow: Troy Aikman – Quarterback – 1989–2000 Dallas Cowboys Harry Carson – Linebacker – 1976-1988 New York Giants L.C. Greenwood – Defensive End – 1969-1981 Pittsburgh Steelers Russ Grimm – Guard – 1981-1991 Washington Redskins Claude Humphrey – Defensive End – 1968-1978 Atlanta Falcons, 1979-1981 Philadelphia Eagles (injured reserve – 1975) Michael Irvin – Wide Receiver – 1988-1999 Dallas Cowboys Bob Kuechenberg – Guard – 1970-1984 Miami Dolphins