Illustrations from the Wellcome Institute Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kennel Hill Cottage, Bridge Road, Butlers Marston, CV35 0ND £360,000

Kennel Hill Cottage, Bridge Road, Butlers Marston, CV35 0ND £360,000 Beautiful detached stone cottage full of character offering spacious sitting room with stone fireplace, dining kitchen, study/office, dual aspect master bedroom with ensuite, two further bedrooms, bathroom and private rear garden with fields to rear. Viewing essential to appreciate this deceptively spacious cottage. BUTLERS MARSTON Butlers Marston is a village and civil DINING KITCHEN Comprising base cupbaords and glazed BEDROOM Dual aspect master bedroom, double glazed parish on the River Dene in South Warwickshire and is located wall display unit, solid wood work surface, Belfast sink, recess window to side with oak sill and exposed timber over, double one mile south-west of Kineton and roughly four miles south-east with Rangemaster cooker and exposed timber over, ornamental glazed window to rear with oak sill, feature recess, exposed of Wellesbourne. fireplace, two double glazed windows to front aspect with oak floorboards, radiator, oak latch door to ensuite. window seats, third double glazed window to front with oak sill, ENSUITE Corner shower cubicle, shelved unit with sink, WC, ENTRANCE via timber door with step down in to sitting room. tiled flooring, space for fridge freezer, radiator and steps up to heated towel rail, tiled flooring, tiling to splash back, extractor utility. fan. SITTING ROOM Spacious sitting room with beautiful stone UTILITY Double glazed window to rear, central heating boiler, BATHROOM Double glazed window to front, bath with mixer fireplace with exposed timber over, log burner and slate hearth, space and plumbing for washing machine, exposed beams, tap and shower attachment, heated towel rail, WC, work exposed beams, double glazed window to front aspect with oak tiled flooring, under stairs storage cupboard, stable style door to surface with inset wash hand basin, shaver point. -

An Index to Warwickshire History, Vols I

An index to Warwickshire History, Vols I - XVII compiled by Christine Woodland The first (roman) figure given in the references is the volume number; the second (arabic) figure is the issue number, the third figure is the page(s) number. ‘author’ after a personal name indicates the author of an article. Please contact the compiler with corrections etc via [email protected] XVI, 5, 210-14 A Alcester C16 murder and inventory Accessions to local record offices: see VIII, 6, 202-4 Archives Alcester Rural Sanitary Authority and Alcester Rural District Council, 1873- Agriculture 1960 agricultural labourers in Wellesbourne after XV, 1, 19-28 1872 Alcester Waterworks Company, 1877-1948 XII, 6, 200-7 XV, 1, 19-28 Brailes and 1607 survey XI, 5, 167-181 Almshouses: see poor law Cistercian estate management I, 3, 21-8 Alveston estate management, C15 manor, C19 X, 1, 3-18 VIII, 4, 102-17 Merevale Abbey, 1490s merestones IX, 3, 87-104 XII, 6, 253-63 land agents used by Leigh family of Stoneleigh, C19 America XI, 4, 141-9 transportation to, 1772-76 farming, C19 X, 2, 71-81 I, 1, 32 farm inventories, 1546-1755 Anthroponymy in Warwickshire, 1279-80 I, 5, 12-28 IX, 5, 172-82 I, 6, 32 hedge dating Apothecaries: see health I, 3, 30-2 mill ponds and fish ponds Apprenticeship IV, 6, 216-24 attorney and apprentice V, 3, 94-102 III, 5, 169-80 National Agricultural Labourers’ Union and Coventry apprentices and masters, 1781- Thomas Parker (1838-1912) 1806 X, 2, 47-70 V, 6, 197-8 plough making in Langley, C19-C20 XII, 2, 68-80 Archaeology trade unionism, C19-C20 brick-making, C18 X, 2, 47-70 VIII, 1, 3-20 see also enclosure and manorial system development in Stratford-upon-Avon, C20 IV, 1, 37 Alexander, M. -

Land and Building Asset Schedule 2018

STRATFORD ON AVON DISTRICT COUNCIL - LAND AND BUILDING ASSETS - JANUARY 2018 Ownership No Address e Property Refere Easting Northing Title: Freehold/Leasehold Property Type User ADMINGTON 1 Land Adj Greenways Admington Shipston-on-Stour Warwickshire 010023753344 420150 246224 FREEHOLD LAND Licence ALCESTER 1 Local Nature Reserve Land Off Ragley Mill Lane Alcester Warwickshire 010023753356 408678 258011 FREEHOLD LAND Leasehold ALCESTER 2 Land At Ropewalk Ropewalk Alcester Warwickshire 010023753357 408820 257636 FREEHOLD LAND Licence Land (2) The Corner St Faiths Road And Off Gunnings Occupied by Local ALCESTER 3 010023753351 409290 257893 FREEHOLD LAND Road Alcester Warwickshire Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 4 Bulls Head Yard Public Car Park Bulls Head Yard Alcester Warwickshire 010023389962 408909 257445 FREEHOLD LAND Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 5 Bleachfield Street Car Park Bleachfield Street Alcester Warwickshire 010023753358 408862 257237 FREEHOLD LAND Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 6 Gunnings Bridge Car Park School Road Alcester Warwickshire 010023753352 409092 257679 LEASEHOLD LAND Authority LAND AND ALCESTER 7 Abbeyfield Society Henley Street Alcester Warwickshire B49 5QY 100070204205 409131 257601 FREEHOLD Leasehold BUILDINGS Kinwarton Farm Road Public Open Space Kinwarton Farm Occupied by Local ALCESTER 8 010023753360 409408 258504 FREEHOLD LAND Road Kinwarton Alcester Warwickshire Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 9 Land (2) Bleachfield Street Bleachfield Street Alcester Warwickshire 010023753361 408918 256858 FREEHOLD LAND Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 10 Springfield Road P.O.S. -

Council Land and Building Assets

STRATFORD ON AVON DISTRICT COUNCIL - LAND AND BUILDING ASSETS - JANUARY 2017 Ownership No Address e Property Refere Easting Northing Title: Freehold/Leasehold Property Type User ADMINGTON 1 Land Adj Greenways Admington Shipston-on-Stour Warwickshire 010023753344 420150 246224 FREEHOLD LAND Licence ALCESTER 1 Local Nature Reserve Land Off Ragley Mill Lane Alcester Warwickshire 010023753356 408678 258011 FREEHOLD LAND Leasehold ALCESTER 2 Land At Ropewalk Ropewalk Alcester Warwickshire 010023753357 408820 257636 FREEHOLD LAND Licence Land (2) The Corner St Faiths Road And Off Gunnings Occupied by Local ALCESTER 3 010023753351 409290 257893 FREEHOLD LAND Road Alcester Warwickshire Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 4 Bulls Head Yard Public Car Park Bulls Head Yard Alcester Warwickshire 010023389962 408909 257445 FREEHOLD LAND Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 5 Bleachfield Street Car Park Bleachfield Street Alcester Warwickshire 010023753358 408862 257237 FREEHOLD LAND Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 6 Gunnings Bridge Car Park School Road Alcester Warwickshire 010023753352 409092 257679 LEASEHOLD LAND Authority LAND AND ALCESTER 7 Abbeyfield Society Henley Street Alcester Warwickshire B49 5QY 100070204205 409131 257601 FREEHOLD Leasehold BUILDINGS Kinwarton Farm Road Public Open Space Kinwarton Farm Occupied by Local ALCESTER 8 010023753360 409408 258504 FREEHOLD LAND Road Kinwarton Alcester Warwickshire Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 9 Land (2) Bleachfield Street Bleachfield Street Alcester Warwickshire 010023753361 408918 256858 FREEHOLD LAND Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 10 Springfield Road P.O.S. -

Public Transport Map Acocks Green R

WARWICKSHIRE CD INDEX TO PLACES SERVED WARWICKSHIRE BUS SERVICES IN WARWICKSHIRE A L Edingdale Public Transport Map Acocks Green R ............................... B3 Langley............................................. B4 Warwickshire Adderley Park R ............................... A3 Langley Green R .............................. A3 Public Transport Map SERVICE ROUTE DESCRIPTION OPERATOR DAYS OF NORMAL SERVICE ROUTE DESCRIPTION OPERATOR DAYS OF NORMAL 82 R NUMBER CODE OPERATION FREQUENCY NUMBER CODE OPERATION FREQUENCY 7 Alcester ............................................. A5 Lapworth ...................................... B4 June 2016 Clifton Campville Alderminster ...................................... C6 Lawford Heath ...................................D4 Measham Alexandra Hospital ............................. A4 Lea Hall R....................................... B3 March 2017 1/2 Nuneaton – Red Deeps – Attleborough SMR Mon-Sat 15 Minutes 115 Tamworth – Kingsbury – Hurley AMN Mon-Sat Hourly Elford Harlaston Allen End........................................... B2 Lea Marston ...................................... B2 PUBLIC TRANSPORT MAP 82 Allesley ............................................. C3 Leamington Hastings..........................D4 Newton Alvechurch R ................................... A4 Leamington Spa R............................ C4 1/2 P&R – Stratford – Lower Quinton – Chipping Campden – JH Mon-Sat Hourly 116 Tamworth – Kingsbury – Curdworth – Birmingham AMN Mon-Sat Hourly 7 Burgoland 224 Alvecote ........................................... -

Nall Geo. Solr. & Agt. to the Wrighted

• lUNE'lON HUNDRED W .A.RWICK DIVISION. 743 J a.rrett, Shipston dist.; relieving officers, Edward Rouse Wheatcroft, Campden dist.; Charles Holland, Brailes dist. ; Stephen J arrett, Shipston dist. ; J ames Hunt, auditor ; and The Right Hon. Lord Redesdale, chairman. The County Court comprises the following places, viz. : Admington, Batsford, Bourton-on-the-IIill, Campden, Clopton, Ebrington, Hidcote, Leamington, Mickleton, Moreton-in-Marsh, Quinton, and Todenham, in the county of Gloucester; Barchester, Brailes, Burmington, Butlers Marston, Cherrington, Compton W ynyates, Halford, Honington, ldlicote, Ilmington, Oxhill, Pillerton Hersey, Pillerton Priors, Stretton-on Foss, Stourton, Sutton, Tysoe, Whatcote, Whichford, W olford Great, and W olford Little, in the county of Warwick; Blockley, Shipston-ou-Stour, Tidmington, and Tred ington, in the county of Worcester: Frederick Trotter Dinsdale, Esq., judge; Edw.V ere Nicoll, Esq., clerk. SHIPSTON-ON-STOUR DIRECTORY. POST OFFICE at Mr. Rd. Brain's. Letters arrive at 7-40.a. m.; dispatched 5-18 p. m. ; box closes 4-15 p.m. Letters arrive from Chipping N orton, 5-3 p.m., despatched at 7-55 p.m. Adams Geo. stone mason FreemanE. plmb.pntr.&glzr. Nelson Geo. grave-stone ctr Adkins Edmund, tanner Freeman J oseph, beerhouse Newton J no. tailor Alder Mrs. Ann Gardner John, builder Nicoll Edw. V ere, solr. and Ash field G eo. gardener Gardner Mary, shopkeeper clt'rk, County Court Ashfield J ane, tailoress Gardner Thos. shoe maker Parker Harry. builder Badger Fras. grocer Gardner Th. carptr. & joiner Parker Mrs. Ann Badger John, draper Gibbs Wm. shoe maker Parker John, beerhouse Badger Rd. senr. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Report No. 186 LOCAL GOVERNMENT

Local Government Boundary Commission For England Report No. 186 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGIiAND REPORT NO. 186. LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Sir Edmund Compton GCB KBE DEPUTY CHAIRMAN Mr J M Rankin QC MEMBERS Lady Bowden Mr J T Brockbank Professor Michael Chisholm Mr R R Thornton CB DL Sir Andrew Wheatley CBE PW To the Rt Hon Merlyn Rees, MP Secretary of State for the Home Department PROPOSALS FOR FUTURE ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE STRATFOHD-ON-AVON DISTRICT OF THE COUNTY OF WARWICKSHIRE 1. We, the Local Government Boundary Commission for England, having carried out our initial review of the electoral arrangements for the district of Stratford-on-Avon in accordance with the requirements of section 63 of, and Schedule 9 to, the Local Government Act 1972, present our proposals for the future electoral arrangements of that district* 2* In accordance with the procedure laid down in section 60(1) and (2) of the 1972 Act, notice was given on 31 December 197^ that we were to undertake this review. This was incorporated in a consultation letter addressed to Stratford- on-Avon District Council, copies of which were circulated to Warwickshire County Council, Parish Councils and Parish Meetings in the district, the Member of Parliament for the constituency.concerned and the headquarters of the main political parties. Copies were also sent to the editors of the local newspapers circulating in the area and to the local government press* Notices inserted in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from members of the public and from any interested bodies. -

Parish Statement of Persons Nominated

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED Stratford-on-Avon District Council District Council Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Parish Councillor for Avon Dassett Reason why Name of Description Name of Proposer (*), Seconder (**) Home Address no longer Candidate (if any) and Assentors nominated* BAXTER Flat 4, Bitham Woolley David R * Philip Hall, Church Hill, Marsh Sharon D ** Avon Dassett, Southam, CV47 2AH BLAKEMAN (Address in Independent Gill Trevor B * Mike Stratford-on-Avon Gill Michele ** District) GILL (Address in Bianciardi Tracey L * Trevor Barrie Stratford-on-Avon Bianciardi Steven G District) A ** HEARD (Address in Bianciardi Tracey L * Martyn John Stratford-on-Avon Bianciardi Steven G District) A ** HIRST (Address in Bianciardi Tracey L * Liz Stratford-on-Avon Bianciardi Steven G District) A ** MUFFITT (Address in Bianciardi Tracey L * Darrell John Stratford-on-Avon Bianciardi Steven G District) A ** The persons above, where no entry is made in the last column, have been and stand validly nominated. Dated Thursday 4 April 2019 David Dalby Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Elizabeth House, Church Street, Stratford-upon-Avon, CV37 6HX STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED Stratford-on-Avon District Council District Council Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Parish Councillor for Beaudesert Reason why Name of Description Name of Proposer (*), Seconder (**) Home Address no longer -

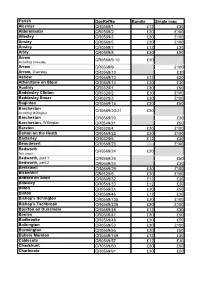

Tithe Maps Pricelist

Parish DocRefNo Bundle Single map Alcester CR0569/1 £12 £30 Alderminster CR0569/2 £30 £100 Allesley CR0569/3 £30 £100 Ansley CR0569/5 £30 £100 Anstey CR0569/7 £12 £30 Arley CR0569/8 £30 £50 Arrow CR0569/9-10 £30 including Oversley Arrow CR0569/9 £100 Arrow, Oversley CR0569/10 £30 Ashow CR0569/13 £12 £30 Atherstone on Stour CR0569/14 £30 £30 Austrey CR0328/1 £30 £50 Baddesley Clinton CR0328/2 £30 £100 Baddesley Ensor CR0328/3 £30 £100 Baginton CR0569/15 £30 £50 Barcheston CR0569/20-21 £30 including Willington Barcheston CR0569/20 £30 Barcheston, Willington CR0569/21 £50 Barston CR0328/4 £30 £100 Barton on the Heath CR0569/22 £30 £100 Baxterley CR0328/5 £12 £30 Beaudesert CR0569/23 £30 £100 Bedworth CR0569/24 £30 two maps Bedworth, part 1 CR0569/24 £50 Bedworth, part 2 CR0569/24 £30 Berkswell CR0569/29 £30 £100 Bickenhill CR0328/6 £30 £100 Bidford on Avon CR0569/32 £12 £30 Billesley CR0569/33 £12 £30 Bilton CR0569/34 £30 £50 Binton CR0569/45 £12 £30 Bishop's Itchington CR0569/135 £30 £100 Bishop's Tachbrook CR0569/236 £30 £100 Bourton on Dunsmore CR0569/46 £12 £30 Brailes CR0569/47 £30 £50 Budbrooke CR0569/48 £30 £50 Bulkington CR0569/53 £30 £100 Burmington CR0569/56 £30 £50 Butlers Marston CR0569/169 £12 £30 Caldecote CR0569/57 £12 £30 Chadshunt CR0569/60 £30 £50 Charlecote CR0569/61 £30 £50 Parish DocRefNo Bundle Single map Chesterton CR0569/62-63 £30 Great and Parva Great Chesterton CR0569/62 £50 Kingston otherwise Chesterton Parva CR0569/63 £30 Church Lawford CR0569/154 £30 £50 Claverdon and Norton Lindsey CR0569/65 £30 £100 Clifton -

Division Arrangements for Galley Common

Hartshill Hartshill & Mancetter Camp Hill Ansley Warwickshire Galley Common Stockingford Astley Arbury Arley Coleshill South & Arley County Division Parish 0 0.125 0.25 0.5 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 Galley Common © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Division Arrangements for 100049926 2016 Dordon Grendon Grendon Baddesley & Dordon Baddesley Ensor Atherstone Merevale Atherstone Baxterley Kingsbury Mancetter Bentley Kingsbury Caldecote Hartshill Hartshill & Mancetter Weddington Warwickshire Nether Whitacre Ansley Camp Hill Stretton Baskerville Galley Common Fosse Over Whitacre Nuneaton Abbey Nuneaton East Stockingford Shustoke Arley Burton Hastings Arbury Attleborough Astley Bulkington & Whitestone Maxstoke Fillongley Coleshill South & Arley Wolvey Bedworth North Bedworth Central County Division Parish 0 0.5 1 2 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 Hartshill & Mancetter © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Division Arrangements for 100049926 2016 Benn Fosse Clifton upon Dunsmore Eastlands New Bilton & Overslade Warwickshire Hillmorton Bilton & Hillside Dunsmore & Leam Valley Dunchurch County Division Parish 0 0.2 0.4 0.8 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 Hillmorton © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Division Arrangements for 100049926 2016 Burton Green Burton Green Lapworth & West Kenilworth Kenilworth Park Hill Stoneleigh Warwickshire Kenilworth Cubbington & Leek Wootton Kenilworth St John's -

![TRADES DIRECTORY.] F..!R 359 Tomlin Frederick, Bird-In-Hand,Ullen- Waddington John, Cawston, Rugby 'Warren George P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5015/trades-directory-f-r-359-tomlin-frederick-bird-in-hand-ullen-waddington-john-cawston-rugby-warren-george-p-2495015.webp)

TRADES DIRECTORY.] F..!R 359 Tomlin Frederick, Bird-In-Hand,Ullen- Waddington John, Cawston, Rugby 'Warren George P

TRADES DIRECTORY.] F..!R 359 Tomlin Frederick, Bird-in-Hand,Ullen- Waddington John, Cawston, Rugby 'Warren George P. The :Meers, Bal- hall, Birmingham Wadland H. Avon Dassett, Lmgtn.Spa sail, Coventry Tomlin Henry, Kineton, Warwick Wady Thos. 0. Warmington, Banbury Warwickshire Omnty Council Dairy Tomlin John, Blunt's green, Ullen.- Wartkins J. Stourton, Shipstn.-on-Str Co. (John Glover, manager), Whit- hall, Birznjngham Turner John, So we, Coventry acre, Coles hill Tomlin Mrs. Lighthurne, Warwick Turner Richd. Knight.cote, Leamngtn Wa<:hbroak ~Irs. Hannah, Poor's Platt, Tomlin Thomas, Knowle, Birmingham Turvey .A.braham, Olton end, Soli- Leamington Hastings, Rugby T&mlin William, Chapel gates, Ullen- hull, Birmingham Watkins Thomas, Ascott. '-'nich!ord., hall, Birmingham Tyacke R. Priory, Maxstoke, B'hm Shipston-on-Stour 'l'omlinson Charle<S Rerbert, Solihull Underhill A. Longmore, Shirley, B'hm Watson Charles Rushworth,KenilwoTth lOO.ge, King's Heath, Birmingham Underhill Mrs. C. Shirley, Birminghm Watson Thos. Whitacre hall, Nether Thmlinson Francis C.O. The V:illa, UptoTh James, Waiter & Alfred, Hurley Whztacre Wolvey, Hinckley hall, Tamworth Watson Waiter William, Manor house, 'Tomlinson William Henry, Bentley Upton Jsph. & Job, Bentley, Atherstne Grandborough, Rugby heath. Knowle, Birmingham Upton William, Austrey, Atherstone Watson W. Nunhold, Hatton, Warwjck Tompson J.Baddesley-Ensor,Athrstne Usher Thomas, Austrey, Atherstone Watson William, Sowe, Coventry TompsO'III Thomas, Halt hall, Over Veasey C. Chilvers CotGn., Nuneaton Watts Miss Betsy, Little Kineton,Wrwk Whitacre, Birrnjngham irain Richard, Malvern hall, Learning- Watts John. Pillerton Priors, Warwick Tonks David, Mancetter, Atherstone ton Hastings, Rugby Weatherspoon Alexander, Kirby lodge, Tonks Rchd. KingswoGd, Birmingham \'Yainwright John, Limestone. -

Parish Notice of Election

NOTICE OF ELECTION Stratford-on-Avon District Council Thursday 2nd May 2019 Election of Parish Councillors for the Parishes listed below Number of Parish Councillors Parishes to be elected Admington Five Alcester (Alcester West Ward) Five Alcester (Oversley Green Ward) One Alcester (Oversley Ward) Ten Alderminster Seven Arrow with Weethley Five Aston Cantlow Six Avon Dassett Five Barton-on-the-Heath Five Bearley Seven Beaudesert Five Bidford-on-Avon (Bidford East Ward) Six Bidford-on-Avon (Bidford West Ward) Three Bidford-on-Avon (Broom Ward) One Binton Seven Bishops Itchington Ten Brailes Seven Burton Dassett (Burton Dassett Ward) Four Burton Dassett (Knightcote Ward) Two Burton Dassett (Temple Herdewyke Ward) Two Butlers Marston Five Cherington Three Claverdon Seven Clifford Chambers and Milcote Six Combrook Five Coughton Five Dorsington Five Ettington (Ettington Ward) Eight Ettington (Fulready Ward) One Exhall Five Farnborough Seven Fenny Compton Seven Gaydon Seven Great Alne Five Great Wolford Five Halford Five Hampton Lucy Five Harbury (Deppers Bridge Ward) One Harbury (Harbury Ward) Nine Haselor Five Henley-in-Arden Seven Ilmington and Compton Scorpion Six Kineton Seven Kinwarton Eight Ladbroke Five Langley Five Lighthorne Six Dated Tuesday 19 March 2019 David Dalby Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Elizabeth House, Church Street, Stratford-upon-Avon, CV37 6HX Lighthorne Heath Eight Little Compton Five Long Compton Eight Long Itchington Nine Long Marston Seven Loxley Six Luddington (Luddington East