Geographic Correlation Between Hot Spots and Deep Mantle Lateral Shear-Wave Velocity Gradients Michael S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C"""- Signature of Author, Joint Program in Oceanography Massachusetts Institute of Technology/ Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

GLOBAL ISOTOPIC SIGNATURES OF OCEANIC ISLAND BASALTS by LYNN A. OSCHMANN A.B. BRYN MAWR COLLEGE (1989) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN OCEANOGRAPHY at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY and the WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION August 1991 @Lynn A. Oschmann 1991 The author hereby grants to MIT, WHOI, and the U.S. Government permission to reproduce and distribute copies of this thesis in whole or in part. %/7_ ) C"""- Signature of Author, Joint Program in Oceanography Massachusetts Institute of Technology/ Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Certified by - 1% Dr. Stanley R. Hart Senior Scientist, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Dr. G. Pat Lohman Chairman, Joint Committee for Geology and Geophysics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology/ Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution MVIr 2 GLOBAL ISOTOPIC SIGNATURES OF OCEANIC ISLAND BASALTS by LYNN A. OSCHMANN Submitted to the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Department of Geology and Geophysics Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution August 9, 1991 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN OCEANOGRAPHY ABSTRACT Sr, Nd and Pb isotopic analyses of 477 samples representing 30 islands or island groups, 3 seamounts or seamount chains, 2 oceanic ridges and 1 oceanic plateau [for a total of 36 geographic features] are compiled to form a comprehensive oceanic island basalt [OIB] data set. These samples are supplemented by 90 selected mid-ocean ridge basalt [MORB] samples to give adequate representation to MORB as an oceanic basalt end-member. This comprehensive data set is used to infer information about the Earth's mantle. -

Aula 4 – Tipos Crustais Tipos Crustais Continentais E Oceânicos

14/09/2020 Aula 4 – Tipos Crustais Introdução Crosta e Litosfera, Astenosfera Crosta Oceânica e Tipos crustais oceânicos Crosta Continental e Tipos crustais continentais Tipos crustais Continentais e Oceânicos A interação divergente é o berço fundamental da litosfera oceânica: não forma cadeias de montanhas, mas forma a cadeia desenhada pela crista meso- oceânica por mais de 60.000km lineares do interior dos oceanos. A interação convergente leva inicialmente à formação dos arcos vulcânicos e magmáticos (que é praticamente o berço da litosfera continental) e posteriormente à colisão (que é praticamente o fechamento do Ciclo de Wilson, o desparecimento da litosfera oceânica). 1 14/09/2020 Curva hipsométrica da terra A área de superfície total da terra (A) é de 510 × 106 km2. Mostra a elevação em função da área cumulativa: 29% da superfície terrestre encontra-se acima do nível do mar; os mais profundos oceanos e montanhas mais altas uma pequena fração da A. A > parte das regiões de plataforma continental coincide com margens passivas, constituídas por crosta continental estirada. Brito Neves, 1995. Tipos crustais circunstâncias geométrico-estruturais da face da Terra (continentais ou oceânicos); Característica: transitoriedade passar do Tempo Geológico e como forma de dissipar o calor do interior da Terra. Todo tipo crustal adveio de um outro ou de dois outros, e será transformado em outro ou outros com o tempo, toda esta dança expressando a perda de calor do interior para o exterior da Terra. Nenhum tipo crustal é eterno; mais "duráveis" (e.g. velhos Crátons de de "ultra-longa duração"); tipos de curta duração, muitas modificações e rápida evolução potencial (como as bacias de antearco). -

Absolute Plate Motions Constrained By

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 114, B10405, doi:10.1029/2009JB006416, 2009 Click Here for Full Article Absolute plate motions constrained by shear wave splitting orientations with implications for hot spot motions and mantle flow Corne´ Kreemer1 Received 27 February 2009; revised 11 June 2009; accepted 14 July 2009; published 22 October 2009. [1] Here, I present a new absolute plate motion model of the Earth’s surface, determined from the alignment of present-day surface motions with 474 published shear wave (i.e., SKS) splitting orientations. When limited to oceanic islands and cratons, splitting orientations are assumed to reflect anisotropy in the asthenosphere caused by the differential motion between lithosphere and mesosphere. The best fit model predicts a 0.2065°/Ma counterclockwise net rotation of the lithosphere as a whole, which revolves around a pole at 57.6°S and 63.2°E. This net rotation is particularly well constrained by data on cratons and/or in the Indo-Atlantic region. The average data misfit is 19° and 24° for oceanic and cratonic areas, respectively, but the normalized root-mean-square misfits are about equal at 5.4 and 5.2. Predicted plate motions are very consistent with recent hot spot track azimuths (<8° on many plates), except for the slowest moving plates (Antarctica, Africa, and Eurasia). The difference in hot spot propagation vectors and plate velocities describes the motion of hot spots (i.e., their underlying plumes). For most hot spots that move significantly, the motions are considerably smaller than and antiparallel to the absolute plate velocity. Only when the origin depth of the plume is considered can the hot spot motions be explained in terms of mantle flow. -

Young Tracks of Hotspots and Current Plate Velocities

Geophys. J. Int. (2002) 150, 321–361 Young tracks of hotspots and current plate velocities Alice E. Gripp1,∗ and Richard G. Gordon2 1Department of Geological Sciences, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97401, USA 2Department of Earth Science MS-126, Rice University, Houston, TX 77005, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Accepted 2001 October 5. Received 2001 October 5; in original form 2000 December 20 SUMMARY Plate motions relative to the hotspots over the past 4 to 7 Myr are investigated with a goal of determining the shortest time interval over which reliable volcanic propagation rates and segment trends can be estimated. The rate and trend uncertainties are objectively determined from the dispersion of volcano age and of volcano location and are used to test the mutual consistency of the trends and rates. Ten hotspot data sets are constructed from overlapping time intervals with various durations and starting times. Our preferred hotspot data set, HS3, consists of two volcanic propagation rates and eleven segment trends from four plates. It averages plate motion over the past ≈5.8 Myr, which is almost twice the length of time (3.2 Myr) over which the NUVEL-1A global set of relative plate angular velocities is estimated. HS3-NUVEL1A, our preferred set of angular velocities of 15 plates relative to the hotspots, was constructed from the HS3 data set while constraining the relative plate angular velocities to consistency with NUVEL-1A. No hotspots are in significant relative motion, but the 95 per cent confidence limit on motion is typically ±20 to ±40 km Myr−1 and ranges up to ±145 km Myr−1. -

Tahiti: Geochemical Evolution of a French Polynesian Volcano

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 99, NO. B12, PAGES 24,341-24,357, DECEMBER 10, 1994 Tahiti: Geochemical evolution of a French Polynesian volcano Robert A. Duncan and Martin R. Fisk Collegeof Oceanicand AtmosphericSciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis William M. White Departmentof GeologicalSciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York Roger L. Nielsen Collegeof Oceanicand Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis Abstract. The island of Tahiti, the largestin French Polynesia,comprises two major volcanoes alignedNW-SE, parallelwith the generaltrend of the SocietyIslands hotspot track. Rocksfrom this volcanicsystem are basaltstransitional to tholeiites,alkali basalts,basanites, picrites, and evolvedlavas. Through K-Ar radiometricdating we haveestablished the ageof volcanicactivity. The oldestlavas (--1.7 Ma) crop out in deeplyeroded valleys in the centerof the NW volcano (Tahiti Nui), while the main exposedshield phase erupted between 1.3 and 0.6 Ma, and a late- stage,valley-filling phase occurred between 0.7 and0.3 Ma. The SW volcano(Tahiti Iti) was active between0.9 and 0.3 Ma. There is a clear changein the compositionof lavas throughtime. The earliestlavas are moderatelyhigh SiO2,evolved basalts (Mg number(Mg# = Mg/Mg+Fe2+) 42-49), probablyderived from parentalliquids of compositiontransitional between those of tholeiitesand alkali basalts.The main shieldlavas are predominantlymore primitive olivine and clinopyroxene-phyricalkali basalts(Mg# 60-64), while the latervalley-filling lavas are basanitic (Mg# 64-68) andcommonly contain peridotitic xenoliths (olivine+orthopyroxene+ clinopyroxene+spinel). Isotopic compositions also change systematically with time to more depletedsignatures. Rare earthelement patterns and incompatible element ratios, however, show no systematicvariation with time.We focusedon a particularlywell exposedsequence of shield- buildinglavas in the PunaruuValley, on the westernside of Tahiti Nui. -

Ridge-Hotspot Interactions What Mid-Ocean Ridges Tell Us About Deep Earth Processes Jérome Dyment, Jiang Lin, Edward Baker

Ridge-hotspot interactions What Mid-Ocean Ridges Tell Us About Deep Earth Processes Jérome Dyment, Jiang Lin, Edward Baker To cite this version: Jérome Dyment, Jiang Lin, Edward Baker. Ridge-hotspot interactions What Mid-Ocean Ridges Tell Us About Deep Earth Processes . Oceanography, Oceanography Society, 2007, 20 (1), pp.102-115. 10.5670/oceanog.2007.84. insu-01309236 HAL Id: insu-01309236 https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-01309236 Submitted on 29 Apr 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. This article has This been published in or collective redistirbution of any portion of this article by photocopy machine, reposting, or other means is permitted only with the approval of The approval portionthe ofwith any permitted articleonly photocopy by is of machine, reposting, this means or collective or other redistirbution S P E C I A L I ss U E F E AT U R E Oceanography , Volume 20, Number 1, a quarterly journal of The 20, Number 1, a quarterly , Volume RIDGE-HOTSPOT InTERACTIOns What Mid-Ocean Ridges Tell Us O About Deep Earth Processes Society. ceanography C BY JÉRÔME DYME N T, J I A N L I N , A nd Ed WAR D T. -

Dana L. Desonie for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Oceanography Presented on September 11

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Dana L. Desonie for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Oceanography presented on September 11. 1990 Title: Geochemical Expression of Volcanism in an On-Axis and Intraplate Hotspot: Cobb and Marguesas Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: Robert A. Duncan The Pacific Ocean basin is home to a set of hotspots diverse in their eruption rate, duration of volcanism, and basalt chemistry. Pacific hotspots are found in a spectrum of distinct plate tectonic settings, from near a spreading ridge to intraplate. Cobb hotspot, which resulted in formation of the Cobb-Eickelberg seamount (CES) chain, is currently located beneath Axial seamount, on the Juan de Fuca ridge. The Marquesas hotspot, which formed the Marquesas archipelago and, perhaps, older seamounts to the west, is a member of the cluster of hotspots found within French Polynesia, located well away from the nearest spreading ridge. Geochemical and geochronological studies of volcanism at these two hotspots contribute to an understanding of the effect of plate tectonic environment on hotspot volcanism. Cobb hotspot has the temporal but not the isotopic characteristics usually attributed to a mantle plume. The earlier volcanic products of the hotspot show a westward age progression away from the hotspot and a westward increase in the age difference between the seamounts and the crust on which they formed. These resultsare consistent with movement of the Pacific plate over a fixed Cobb hotspot and encroachment by the westwardly migrating Juan de Fuca ridge. CES lavas are slightly enriched in alkali and incompatible elements relative to those of the Juan de Fuca ridge but they have Sr, Nd, and Pb isotopic compositions virtually identical to those found along the ridge. -

7.09 Hot Spots and Melting Anomalies G

7.09 Hot Spots and Melting Anomalies G. Ito, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA P. E. van Keken, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA ª 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. 7.09.1 Introduction 372 7.09.2 Characteristics 373 7.09.2.1 Volcano Chains and Age Progression 373 7.09.2.1.1 Long-lived age-progressive volcanism 373 7.09.2.1.2 Short-lived age-progressive volcanism 381 7.09.2.1.3 No age-progressive volcanism 382 7.09.2.1.4 Continental hot spots 383 7.09.2.1.5 The hot-spot reference frame 386 7.09.2.2 Topographic Swells 387 7.09.2.3 Flood Basalt Volcanism 388 7.09.2.3.1 Continental LIPs 388 7.09.2.3.2 LIPs near or on continental margins 389 7.09.2.3.3 Oceanic LIPs 391 7.09.2.3.4 Connections to hot spots 392 7.09.2.4 Geochemical Heterogeneity and Distinctions from MORB 393 7.09.2.5 Mantle Seismic Anomalies 393 7.09.2.5.1 Global seismic studies 393 7.09.2.5.2 Local seismic studies of major hot spots 395 7.09.2.6 Summary of Observations 399 7.09.3 Dynamical Mechanisms 400 7.09.3.1 Methods 400 7.09.3.2 Generating the Melt 401 7.09.3.2.1 Temperature 402 7.09.3.2.2 Composition 402 7.09.3.2.3 Mantle flow 404 7.09.3.3 Swells 405 7.09.3.3.1 Generating swells: Lubrication theory 405 7.09.3.3.2 Generating swells: Thermal upwellings and intraplate hot spots 407 7.09.3.3.3 Generating swells: Thermal upwellings and hot-spot–ridge interaction 408 7.09.3.4 Dynamics of Buoyant Upwellings 410 7.09.3.4.1 TBL instabilities 410 7.09.3.4.2 Thermochemical instabilities 411 7.09.3.4.3 Effects of variable mantle properties 412 7.09.3.4.4 Plume -

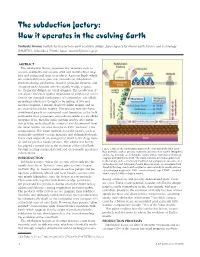

The Subduction Factory: How It Operates in the Evolving Earth

The subduction factory: How it operates in the evolving Earth Yoshiyuki Tatsumi, Institute for Research on Earth Evolution (IFREE), Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), Yokosuka 237-0061, Japan, [email protected] ABSTRACT The subduction factory processes raw materials such as oceanic sediments and oceanic crust and manufactures mag- mas and continental crust as products. Aqueous fluids, which are extracted from oceanic raw materials via dehydration reactions during subduction, dissolve particular elements and overprint such elements onto the mantle wedge to gener- ate chemically distinct arc basalt magmas. The production of calc-alkalic andesites typifies magmatism in subduction zones. One of the principal mechanisms of modern-day, calc-alkalic andesite production is thought to be mixing of two end- member magmas, a mantle-derived basaltic magma and an arc crust-derived felsic magma. This process may also have contributed greatly to continental crust formation, as the bulk continental crust possesses compositions similar to calc-alkalic andesites. If so, then the mafic melting residue after extrac- tion of felsic melts should be removed and delaminated from the initial basaltic arc crust in order to form “andesitic” crust compositions. The waste materials from the factory, such as chemically modified oceanic materials and delaminated mafic lower crust materials, are transported down to the deep man- tle and recycled as mantle plumes. The subduction factory has played a central role in the evolution of the solid Earth through creating continental crust and deep mantle geochemi- Figure 1. Role of the subduction factory in the evolution of the solid Earth. cal reservoirs. -

Age Constraints on Crustal Recycling to the Mantle Beneath the Southern Chile Ridge: He-Pb-Sr-Nd Isotope Systematics

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL 104. NO. B3, PAGES 5097-5114, MARCH 10, 1999 Age constraints on crustal recycling to the mantle beneath the southern Chile Ridge: He-Pb-Sr-Nd isotope systematics Marnie E. Sturm and Emily M. Klein Division of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Nicholas School orthe Environment Duke University. Durham, North Carolina David W. Graham College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis Jill Karsten School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, University of Hawaii at Manca Abstract. Basalts from the four southernmost segments of the subducting Chile Ridge (num- bered 1-4 stepping away from the trench) display large variations in Sr, Nd, Pb, and He isotope and trace element compositions. Klein and Karsten [1995] showed that segments I and 3 display clear trace element evidence for recycled material in their source (e.g.. low CefPb). The uniformly mid- ocean ridge basalt (MORB)-like 3He/4He and modest variations in Pb, Sr. and Nd isotopes of seg- ment 1 (nearest the trench) suggest recent (<20 Ma) introduction of a contaminant into its source, consistent with recycling of material from the adjacent subduction zone. In contrast, segment 3 Ia- vas display a dramatic southward increase in enrichment, extending to highly radiogenic Pb and Sr isotopic compositions (e.g., 206Pb/204Pb = 19.5) and the lowest 3He/4He yet measured in MORB (3.5RA). The segment 3 variations are most readily explained by ancient (-2 Ga) recycling of ter- rigenous sediment and altered cnist, but we cannot rule out more recent recycling of material de- rived from a distant continental source. -

18. Geochemistry and Petrography of Cretaceous Sills and Lava Flows, Sites 800 and 8021

Larson, R. L., Lancelot, Y., et al., 1992 Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Vol. 129 18. GEOCHEMISTRY AND PETROGRAPHY OF CRETACEOUS SILLS AND LAVA FLOWS, SITES 800 AND 8021 P. A. Floyd,2 J. A. Winchester,2 and Paterno R. Castillo3 ABSTRACT On the basis of their respective eruptive environments and chemical characteristics, alkalic dolerite sills from the northern Pigafetta Basin (Site 800) and tholeiitic pillow lavas from the Mariana Basin (Site 802) sampled during Ocean Drilling Program Leg 129 are considered to represent examples of the widespread mid-Cretaceous volcanic event in the western Pacific. Both groups of basic rocks feature mild, low-grade, anoxic smectite-celadonite-carbonate-pyrite alteration; late-stage oxidation is very limited in extent, with the exception of the uppermost sill unit at Site 800. The aphyric and nonvesicular Site 800 alkalic dolerite sills are all well-evolved mineralogically and chemically, being mainly of hawaiite composition, and are similar to ocean island basalts. They are characterized by high contents of incompatible elements (for example, 300-400 ppm Zr), well-fractionated rare earth element patterns ([La/Yb]N 18-21) and HIMU isotopic characters. They probably represent deep-sea, lateral, intrusive off-shoots from nearby seamounts of similar age. The olivine-plagioclase ± clinopyroxene phyric tholeiitic pillow lavas and thin flows of Site 802 are nonvesicular and quench-textured throughout. Relative to normal-type mid-ocean ridge basalt, they are enriched in large-ion-lithophile elements, exhibit flat (unfractionated) rare earth element patterns and have distinctive (lower) Zr/Nb, Zr/Ta, La/Ta, and Hf/Th ratios. -

Genesis of the Western Samoa Seamount Province: Age, Geochemical Fingerprint and Tectonics

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 227 (2004) 37–56 www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl Genesis of the Western Samoa seamount province: age, geochemical fingerprint and tectonics S.R. Harta,*, M. Coetzeeb, R.K. Workmana, J. Blusztajna, K.T.M. Johnsonc, J.M. Sintonc, B. Steinbergerd, J.W. Hawkinse aWoods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA bUniversity of Cape Town, Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa cUniversity of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA dJapan Marine Science and Technology Center, Yokosuka 237-0061, Japan eScripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA Received 11 March 2004; received in revised form 2 August 2004; accepted 5 August 2004 Editor: K. Farley Abstract The Samoan volcanic lineament has many features that are consistent with a plume-driven hotspot model, including the currently active submarine volcano Vailulu’u that anchors the eastern extremity. Proximity to the northern end of the Tonga trench, and the presence of voluminous young volcanism on what should be the oldest (~5 my) western island (Savai’i) has induced controversy regarding a simple plume/hotspot model. In an effort to further constrain this debate, we have carried out geochronological, geochemical and isotopic studies of dredge basalts from four seamounts and submarine banks that extend the Samoan lineament 1300 km further west from Savai’i. 40Ar/39Ar plateau ages from Combe and Alexa Banks (11.1 my—940 km, and 23.4 my—1690 km from Vailulu’u, respectively) fit a Pacific age progression very well. The oldest volcanism (9.8 my) on Lalla Rookh (725 km from Vailulu’u) also fits this age progression, but a new age is much younger (1.6 my).