Ingxembula for Uhadi and Voice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

24Th STANDARD BANK NATIONAL YOUTH JAZZ FESTIVAL 2016

24th STANDARD BANK NATIONAL YOUTH JAZZ FESTIVAL 2016 Welcome to Grahamstown, the National Arts Festival, and the biggest youth jazz festival in South Africa! There are five extremely full days for you to take advantage of and a host of excellent musicians and teachers to meet and hear, as well as a chance to assess yourself against your peers from around the country. The full programme for the Standard Bank National Youth Jazz Festival is outlined below. Thank you to the following institutions and people who have supported us by providing equipment: Paul Bothner Music, Les van der Veen, Eastern Cape Jazz Promotions, Stirling High School, DSG / St. Andrews Music School, UCT College of Music, Rondebosch Boys High, Len Cloete, Kingswood College, The Settlers High School, Little Giants, Bridge House School, Parel Vallei High School, Neville Hartzenberg The Festival Production Office (for performing artists) is in the Music School. The Artists’ Office is Music 2. The NYJF Student Office is Music 3. FESTIVAL RULES 1. Please be punctual for all aspects of the SBNYJF. Everyone must be there – on time – for band rehearsals. 2. We are guests of DSG – please treat the facilities accordingly. Please obey the rules of the hostels and show consideration for others. There is to be no noise after 22.00 and curfew for students in DSG hostels is 00.30. Don’t try to sneak friends in overnight, as you will need to pay in full for their accommodation. 3. Show respect for NYJF equipment. Most of it has been lent to us and needs to be returned in perfect condition. -

Freaky Friday Is a Day That Be- Despicable Are in Full Force and Ready Fun Starts on the Field

the keeping you on the MaP 12.17c mpass A day of tortureFREAKY and misery. A day the younger forms wereFRIDAY greeted by year,” said Lemohang Moriana (1L) where the most feared and power- them on their way to class. The entire All in all, it was a really action-packed ful in school are given freedom: too school then attended an assembly day; a day I know other schools much freedom. A day where flowers that showcases the Form Five talent would not experience, which makes it bloom into ferocious creatures; the one last time. During first break, the unique. Freaky Friday is a day that be- despicable are in full force and ready fun starts on the field. They spread all longs to the form fives. It is a day that to unleash their terrible plans onto the sorts of multi-coloured powder paint allows them to let loose ahead of the world. on everyone. It was an amazing day IGCSE exams. It brings them so much Well, at least that’s what the rumours in general. It was actually not as bad joy. It must be really exciting and a re- said. Spread from generation to gen- as most of the form ones thought it lief to know that there is something to eration, these rumours have been would be. look forward to at the end of one of adapted and have pierced through “It’s not as bad as everyone makes it the hardest years of your life. the souls of the innocent young. out to be. -

We're in This Together

Noteworthy The University of Tennessee School of Music, 2020 We’re in This Together In September 2018, the School of Music began celebrating the works of Ludwig van Beethoven as the 250th anniversary of his birth approached in December 2020. A series of concerts and events focused on the masterpieces of this legendary composer throughout the 2019–20 academic year. One of the feature performances was Beethoven’s 9th Symphony by the UT Symphony Orchestra and Choirs at the historic Tennessee Theatre in February 2020. From the Director I’ve always waited until the very end of the publication process to write these notes, and this year is no different. But that’s where the commonalities stop this year. Anyone who has lived through it (and as we know some have not) will never forget it. As an academic year goes, all was fine until December 2019. Little did we know the force the COVID-19 virus would place on our entire world. Then, although not a new phenomenon, George Floyd, unfortunately, became a household phrase. I don’t need to rehash the derailment both these events brought and continue to bring to our society. 2020 was a year no one in the world will ever forget, and it will rank for Americans like 1929, 1968, 2008, and we now all know 1918. We’ve collectively survived all of these challenges and in some way come out stronger. I believe we will do so again. For our School of Music, 2020 was one of great change, loss, and successes. Each is found within these pages. -

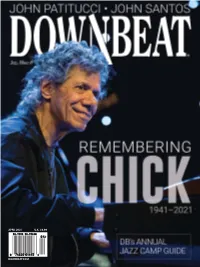

Downbeat.Com April 2021 U.K. £6.99

APRIL 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM April 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Thursday 26Th September Zar Jazz Orchestra

DAY 1- THURSDAY 26TH SEPTEMBER 18:00 18:15 18:30 18:45 19:00 19:15 19:30 19:45 20:00 20:15 20:30 20:45 21:00 21:15 21:30 21:45 22:00 22:15 22:30 22:45 23:00 23:15 23:30 23:45 0:00 0:15 0:30 0:45 1:00 1:15 STANDARD BANK YOUNG ARTIST ALL STAR JAZZ BAND SIBONGILE KHUMALO, GLORIA BOSMAN, MELANIE SCHOLTZ,SHANNON MOWDAY, BOKANI DYER, SHANE COOPER MARK FRANSMAN, NDUDUZO MAKHATHINI, ZAR JAZZ ORCHESTRA with MARCUS WYATT Dinaledi Stage SHANE COOPER, KESIVAN NAIDOO Reserved and SHANNON MOWDAY, MARK FRANSMAN, CONCORD NKABINDE, Seating JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER ORCHESTRA with WYNTON MARSALIS KESIVAN NAIDOO SOUTH AFRICA | USA GLORIA BOSMAN, MANDLA MLANGENI, AFRIKA MKHIZE, VICTOR MASONDO, KESIVAN NAIDOO SOUTH AFRICA DAY 2- FRIDAY 27TH SEPTEMBER 18:00 18:15 18:30 18:45 19:00 19:15 19:30 19:45 20:00 20:15 20:30 20:45 21:00 21:15 21:30 21:45 22:00 22:15 22:30 22:45 23:00 23:15 23:30 23:45 0:00 0:15 0:30 0:45 1:00 1:15 1:30 Dinaledi Stage PROJECT LILA with SHANNON MOWDAY JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER ORCHESTRA MANU KATCHE DON LAKA Unreserved HELGE LIEN | ERIK NYLANDER | JOHANNES EICK with WYNTON MARSALIS FRANCE SOUTH AFRICA Seating SOUTH AFRICA I NORWAY USA 18:00 18:15 18:30 18:45 19:00 19:15 19:30 19:45 20:00 20:15 20:30 20:45 21:00 21:15 21:30 21:45 22:00 22:15 22:30 22:45 23:00 23:15 23:30 23:45 0:00 0:15 0:30 0:45 1:00 1:15 1:30 SANKOFA with SALIM WASHINGTON Diphala Stage STANDARD BANK NATIONAL ZACHUSA WARRIORS with KESIVAN NAIDOO THE JAZZ UNITY with ZOE MODIGA NDUDUZO MAKHATHINI | AYANDA SIKADE KEN PEPLOWSKI Unreserved YOUTH JAZZ BAND REGGIE WASHINGTON | MALCOLM BRAFF NOMFUNDO XALUVA | LAFRAE SCI I LAKECIA BENJAMIN DALISU NDLAZI | SAKHILE SIMANI USA Seating SOUTH AFRICA SOUTH AFRICA I USA I SWISS SOUTH AFRICA I USA ZOE MASUKU | PHUMLANI MTITI SOUTH AFRICA 18:00 18:15 18:30 18:45 19:00 19:15 19:30 19:45 20:00 20:15 20:30 20:45 21:00 21:15 21:30 21:45 22:00 22:15 22:30 22:45 23:00 23:15 23:30 23:45 0:00 0:15 0:30 0:45 1:00 1:15 1:30 Conga Stage KOH MR. -

25 Years of the London Jazz Festival

MUSIC FROM OUT THERE, IN HERE: 25 YEARS OF THE LONDON JAZZ FESTIVAL Emma Webster and George McKay MUSIC FROM OUT THERE, IN HERE: 25 YEARS OF THE LONDON JAZZ FESTIVAL Emma Webster and George McKay Published in Great Britain in 2017 by University of East Anglia, Norwich NR4 7TJ, UK as part of the Impact of Festivals project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, under the Connected Communities programme. impactoffestivals.wordpress.com ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This book is an output of the Arts and Humanities Research Council collaborative project The Impact of Festivals (2015-16), funded under the Connected Communities Programme. The authors are grateful for the research council’s support. At the University of East Anglia, thanks to project administrators CONTENTS Rachel Daniel and Jess Knights, for organising events, picture 1 FOREWORD 50 CHAPTER 4. research, travel and liaison, and really just making it all happen JOHN CUMMING OBE, THE BBC YEARS: smoothly. Thanks to Rhythm Changes and CHIME European jazz DIRECTOR, EFG LONDON 2001-2012 research project teams for, once again, keeping it real. JAZZ FESTIVAL 50 2001: BBC RADIO 3 Some of the ideas were discussed at jazz and improvised music 3 INTRODUCTION 54 2002-2003: THE MUSIC OF TOMORROW festivals and conferences in London, Birmingham, Cheltenham, 6 CHAPTER 1. 59 2004-2007: THE Edinburgh, San Sebastian, Europe Jazz Network Wroclaw and THE EARLY YEARS OF JAZZ FESTIVAL GROWS Ljubljana, and Amsterdam. Some of the ideas and interview AND FESTIVAL IN LONDON 63 2008-2011: PAST, material have been published in the proceedings of the first 7 ANTI-JAZZ PRESENT, FUTURE Continental Drifts conference, Edinburgh, July 2016, in a paper 8 EARLY JAZZ FESTIVALS 69 2012: FROM FEAST called ‘The role of the festival producer in the development of jazz (CULTURAL OLYMPIAD) in Europe’ by Emma Webster. -

Joy of Jazz Festival, Grahamstown 2004

Standard Bank Jazz Festival, Grahamstown 2015 (Incorporating the Standard Bank National Youth Jazz Festival) Support funding from: The Austrian Embassy Brian Meese Dutch Fund of the Performing Arts The French Institute of South Africa Paul Bothner Music ProHelvetia Johannesburg The Royal Netherlands Embassy SAfm SAMRO Spedidam Swedish Arts Council / Swedish Jazz Federation / Mary Lou Meese Youth Jazz Fund Swiss Arts Council The US Embassy Thursday 2 July Bokani Dyer Quintet Contemporary South African Jazz meets Swiss precision Bokani Dyer has had a meteoric rise in the jazz world, winning the Standard Bank Young Artist Award at age 25 and garnering invitations to international festivals such as the London Jazz Festival. As part of his extensive 2014 European tour he performed with four gifted representatives of the Swiss jazz scene whom he had met during his residency at the Bird’s Eye Jazz Club in Basel, and the vitality of contemporary South African Jazz meets Swiss precision and musicianship in this outstanding collaboration. Dyer’s music is all-encompassing, embracing his roots as well as the contemporary musical landscape of South Africa. Bokani Dyer (piano), Donat Fisch (sax - CH), Matthias Spillmann (trumpet – CH), Stephan Kurrman (bass - CH), Norbert Pfammatter (drums - CH) DSG Hall Thursday 2 July 17:00 R80 Carlo Mombelli & the Storytellers Manipulated bass and sound design “Disconcertingly beautiful” was the comment on Carlo Mombelli’s playing from The Jazz Times – the world’s leading jazz periodical. The US Bass Player Magazine’s view was that “Avant-garde bass-focused jazz composition has rarely sounded so gorgeous....Once in a while an artist comes along who produces music unlike anything you’ve heard.” Having played sold out concerts over the past year to much critical acclaim, this ensemble features the unique composer/bassist Carlo Mombelli, known in South Africa for his cutting-edge voice-like playing style. -

Hope As a New Country Is Born

VIEWS AND ANALYSES FROM THE AFRICAN CONTINENT ISSUE 14 • 2011 the african.orgwww.the-african.org • THE ALTERNATE-MONTHLY MAGAZINE OF THE INSTITUTE FOR SECURITY STUDIES Hope as a new country is born TROUBLE INSIDE FESTIVALS BREWING ANGOLA’s SHOWCASING IN BURKINA SHADOW AFRICA’s FASO STATE TALENT Angola K500 • Botswana P20.00 • Côte D’Ivoire Cfa3 000 • Democratic Republic of the Congo Cfa3 000 • Ethiopia B20.00 Gambia D50.00 • Ghana C4.00 • Kenya Sh300.00 • Malawi K5 000 • Mozambique R29.00 Namibia $29.00 • Nigeria N500.00 • Tanzania Sh7 000 • Uganda Sh7 000 • Zambia K15 000 • Zimbabwe R29.00 South Africa R29.00 (incl VAT) • UK £4.00 • US $6.00 • Europe €6.95 covers African.org 13.indd 2 2011/05/24 12:04 PM Editorial Nothing like a clean war Dear Reader… soul-searching of why the Libyan air raids Five months down the line the conflict are taking so long to achieve their goal, oth- is still raging – at a huge cost. ers, more cynical, believe the end will not he official inauguration of an inde- even be in sight before the end of the year. Following the dramatic events in pendent South Sudan was for An argument heard in the Arab world North Africa, two previously relatively many an immensely joyful occa- is that the allies – France, Britain and the stable West African countries, Burkina sion, but for others a traumatic US – are confident that the rebuilding of Faso and Senegal, have also experienced Tevent that signalled the failure of ‘making Libya will be portioned out to their com- popular protests. -

Exploring Elements of Musical Style in South African Jazz Pianists by Phuti

Exploring elements of musical style in South African jazz pianists by Phuti Sepuru 28446063 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctorate in Musicology in the School of the Arts: Music Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Supervisor: Prof. Clorinda Panebianco Pretoria – December 2019 The financial assistance of the National Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences, in collaboration with the South African Humanities Deans Association towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed, and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NIHSS and SAHUDA. i DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own original work and that it has not previously been used or submitted for degree purposes at any other University. References have been listed and acknowledged appropriately. Signature: Date: ii “Jazz, as far as I’m concerned, would be an extension or expression of the self. You know, you get all the information, you learn how to paint a picture, and then you paint a picture of your environment. So to tell your story, you learn your craft, and then tell the story in your own words” (Robbie Jansen, in Devroop & Walton, 2007, p. 55) iii ABSTRACT The purpose of this research was to explore the fundamental elements that constitute, shape and define the thinking and creative processes embodied in musical style of ten prominent South African jazz pianists. The study was qualitative and underpinned by an exploratory research design. Using a collection of case studies, the study used semi-structured interviews to probe participants’ backgrounds, formative influences, and musical style within a South African context. -

Www,Nairobiacademy.Or.Ke Secondary Bulletin Vol. 7 Term 2

www,nairobiacademy.or.ke Secondary Bulletin Vol. 7 Term 2, 2017 As most of the school began their half term, appointed senior leaders within the school embarked on Leadership Training with Bluesky this past weekend. The training took place in Lukenya at the Lukenya Get- away, a dry and hot place. Most of us wondered how the Bluesky team were going to effectively train us to lead better, as the day went on we soon learnt as well as realized this. We played games that indeed had a valuable lessons on how we can become better leaders. Personally and also based on what I heard from the majority is that the trip was worthwhile. We arrived, signed in against our names while our rooms were being sorted. We were introduced to the Bluesky team who would be with us for the weekend. We started with a few ice breakers to warm us up, to get our minds active for the activities to come. We had a few activities then had long awaited lunch (the wait was definitely worth it). After lunch, the harder tasks were presented to us namely a game called Di- minishing Resources. Basically, in a circle was a number of mats and between each mat was grass as this was done on a field. The grass represented all bad things while the mats represented all good things in re- lation to being a leader. The aim was to have all mats occupied and no one on the grass (within the cir- cle). The mats kept decreasing while we remained constant in numbers making it harder and harder to have everyone on the mats. -

The Royal Escape Experience 2016 Artist Biographies Lalah Hathaway

The Royal Escape Experience 2016 Artist Biographies Lalah Hathaway (US) The daughter of the great Donny Hathaway, Lalah Hathaway made a good impression with her self-titled debut recording in 1990. She not only displayed poise, confidence, and good technique, but was also versatile enough to do more than just light urban contemporary ballads. Her stage shows included jazz, pre-rock pop, and even gospel, and Hathaway later appeared on BET doing jazz and fusion. After her second and final album for Virgin, 1994's A Moment, she went on a lengthy hiatus, returning in 1999 with Joe Sample for The Song Lives On (GRP). The following decade and into the 2010s she released Outrun the Sky (Sanctuary, 2004), Self Portrait (Stax, 2008), and Where It All Begins (Stax, 2011) -- all fine albums involving collaborations with the likes of Mike City, Rahsaan Patterson, Rex Rideout, and Dre & Vidal. They established Hathaway as one of the finest adult contemporary R&B vocalists of the 2000s and 2010s. A 2013 collaboration with the band Snarky Puppy -- on a cover of Brenda Russell's "Something" -- won a 2014 Grammy Award in the category of Best R&B Performance. The following year, thanks to her role in Robert Glasper Experiment's update of Stevie Wonder's "Jesus Children of America," Hathaway picked up the Grammy for Best Traditional R&B Performance. She then recorded and released Live. A document of back-to-back sets recorded at Los Angeles' Troubadour, the same venue her father played in 1971 -- as heard on the first side of his 1972-released album of the same title -- it was released in 2015. -

MAITISONG 2015 MID-YEAR REVIEW Gao Lemmenyane, Maitisong Director Mophato and Sky Blue Dance Hub Opening the Festival Time Flies When You Are Having Fun

the August 2015 mighty song! MAITISONG 2015 MID-YEAR REVIEW Gao Lemmenyane, Maitisong Director Mophato and Sky Blue Dance Hub opening the Festival Time flies when you are having fun. The first half of the year has come and gone. It was only yesterday when we got back from the December break with a slow start of the year’s activities and earnest festival preparations. From mid-February onwards a buildup of world class entertainment started. Former Maru-a-Pula School student Bokani Dyer and his band graced the Maitisong stage, courtesy of Botswanacraft Marketing. The show was opened by Soul Connect, a newly established band made up of two MaP alumni - pianist Laone Thekiso and drummer Khaya Groth. Joburg Ballet raised the bar and set the tone for the Maitisong Festival. Sponsored by the Israeli diamond company Diacore, the supporters of the Gaborone Diacore Marathon, Joburg Ballet presented three magical and breathtaking performances, one by invitation only and two public performances. This troupe of super flexible male and female dancers pranced gallantly like race horses, twirled like a tropical tornado, leapt skywards with super splits mid-air and distorted pointed feet swirling on the dance floor as they spun. It was electrifying. A personal favourite was the Dying Swan performed brilliantly by Kitty Phetla. Another annual feature at Maitisong is the Ditshwanelo Film Festival. This Moratiwa performing in the year the festival was headlined by the Maru-a-Pula School gardens on harrowing documentary of the August 12th 2012 killings of striking miners in Festival opening night Marikana, South Africa.