Dividend Policy - As Affected by Depreciation and Depletion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wine Industry Audit Technique Guide

The Wine Industry Audit Technique Guide NOTE: This document is not an official pronouncement of the law or the position of the Service and cannot be used, cited, or relied upon as such. This guide is current through the publication date. Since changes may have occurred after the publication date that would affect the accuracy of this document, no guarantees are made concerning the technical accuracy after the publication date. Publication Date: March 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 1 - Overview of Winery/Vineyard Operations ............................................................................ 3 Farming ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Winery (Manufacturing) ....................................................................................................................... 4 Marketing/Sales .................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 2 - Pre-Audit Information Gathering ........................................................................................... 8 Information Sources .............................................................................................................................. 8 Chapter 3 - Audit Considerations ............................................................................................................. -

Capital/Fixed Assets Depreciation Schedule Updated: February 2021

Kentucky Department of Education Munis Guide Capital/Fixed Assets Depreciation Schedule Updated: February 2021 Capital/Fixed Assets Depreciation Schedule Office of Education Technology: Division of School Technology Services Questions?: [email protected] 1 | P a g e Kentucky Department of Education Munis Guide Capital/Fixed Assets Depreciation Schedule Updated: February 2021 OVERVIEW The Fixed Assets Depreciation Schedule provides a listing of asset details that were depreciated for the report year as posted from the Fixed Asset module for the report year. Asset descriptions and depreciation details are included such as estimated life, number of periods taken for the year, first and last year periods of depreciation and acquisition cost; all to assist auditors in verifying the depreciation calculation and amounts. The report also includes assets that have been fully depreciated but have a balance remaining of Life-To-Date accumulated depreciation for the reported year. The asset amounts are reported as posted from the Fixed Asset history detail records generated from the Fixed Asset module and does NOT include amounts generated from General Journal Entries. The Depreciation Schedule pulls from two different Fixed Asset sources: 1. Fixed Asset Master File Maintenance 2. Fixed Asset history records The Fixed Asset Master File Maintenance or Asset Inquiry is where the actual asset master records reside; where assets are added and maintained. Key fields and amounts such as the asset Acquisition cost field, Asset Type (Governmental or Proprietary), Class and Sub-class codes are pulled from the asset master file for the Depreciation Schedule. It is vital that these key fields are accurate and tie to the fixed asset history records. -

14. Calculating Total Cash Flows

Chapter 2 Lecture Problems 14. Calculating Total Cash Flows. Greene Co. shows the following information on its 2008 income statement: Sales = $138,000 Costs = $71,500 Other expenses = $4,100 Depreciation expense = $10,100 Interest expense = $7,900 Taxes = $17,760 Dividends = $5,400. In addition, you're told that the firm issued $2,500 in new equity during 2008, and redeemed $3,800 in outstanding long-term debt. a. What is the 2008 operating cash flow? b. What is the 2008 cash flow to creditors? c. What is the 2008 cash flow to stockholders? d. If net fixed assets increased by $17,400 during the year, what was the addition to NWC? a. To calculate the OCF, we first need to construct an income statement. The income statement starts with revenues and subtracts costs to arrive at EBIT. We then subtract out interest to get taxable income, and then subtract taxes to arrive at net income. Doing so, we get: Income Statement Sales $138,000 Costs 71,500 Other Expenses 4,100 Depreciation 10,100 EBIT $52,300 Interest 7,900 Taxable income $44,400 Taxes 17,760 Net income $26,640 Dividends $5,400 Addition to retained earnings 21,240 Page 1 Chapter 2 Lecture Problems Dividends paid plus addition to retained earnings must equal net income, so: Net income = Dividends + Addition to retained earnings Addition to retained earnings = $26,640 – 5,400 Addition to retained earnings = $21,240 So, the operating cash flow is: OCF = EBIT + Depreciation – Taxes OCF = $52,300 + 10,100 – 17,760 OCF = $44,640 b. -

Capitalization and Depreciation Procedures Policy

Capitalization and Depreciation Procedures Policy Capitalization Policies The following capitalization procedures will be applied to fixed assets as defined by the Financial Accounting and Reporting Manual for Higher Educations (FARM). 1. Land a. Capitalized at cost b. Land and structures purchased or donated together will be separated when possible and capitalized separately c. Cost of preparing the land for use will be capitalized, when material, along with the cost of the land 2. Buildings a. Capitalized if - i. $25,000.00 or more and a life expectancy of at least 10 years b. Additions and renovations will be capitalized if - i. Cost of the project is $25,000.00 or more, and ii. The renovation extends the useful life of the facility or modifies and/or upgrades a building, i.e., installation of updated fire alarms, removal of handicapped barriers, etc 3. Improvements other than buildings a. Capitalized if – i. $5,000.00 or more 1. Examples are parking lots, sidewalks, fiber optics, etc. 4. Equipment a. Capitalized if - i. Cost is $5,000 or more 1. The cost of the equipment will include the purchase price, freight cost, insurance while in shipment, installation cost, and other cost incurred to get the equipment ready for actual use ii. Acquired for use in operations and not held for resale iii. Useful life is long-term in nature - It must yield services for five years or more iv. It is not an integral part of another unit 5. Software a. Capitalized if - i. Cost is $5,000.00 or more ii. Useful life is five years or more iii. -

General IT Controls (GITC) Risk and Impact November 2018 Risk Advisory

General IT Controls (GITC) Risk and Impact November 2018 Risk Advisory General IT Controls (GITC) Table of Contents Introduction 02 IT scoping for evaluation of internal controls 04 Importance of GITC 06 Implications of GITC deficiencies 07 Stepping towards a controlled IT environment 08 Conclusive remarks 13 Impact of GITC failure on the overall ICFR framework 15 Contact 16 01 General IT Controls (GITC) Introduction The importance of information technology (IT) controls has recently caught the attention of organisations using advanced IT products and services. This thought paper has been developed for the management of companies that are required to establish framework on internal controls and to ensure its effective operation throughout the year. This document draws attention on how applications should be scoped-in for monitoring internal controls and how control gaps need to be assessed and concluded. Increasing complexity of the IT setup has resulted in a greater focus around controls in the IT environment. With mandates emanating from various regulations, internal controls have gained more momentum in India during recent years. There is a trend of automation in processes and controls by adoption of advanced IT products and services for enabling greater efficiency in operations, compliance and reporting activities. This requires an increased focus on effective operation of controls around IT assets and services. Internal Financial Controls over Financial Reporting “Internal controls” refers to those activities within a company that are placed by the management to mitigate the risks that could hinder the company from achieving its objectives. Under the Committee on Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) framework revised in May 2013, there are three types of objectives which internal controls need to meet, as depicted below: Compliance Operations Reporting 02 General IT Controls (GITC) In many cases, a control may address more than one of COSO Cube (2013) these objectives. -

Guideline Depreciation & Revenue Procedure 62-21

University of Mississippi eGrove Touche Ross Publications Deloitte Collection 1964 Guideline depreciation & revenue procedure 62-21 Gerald W. Padwe Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/dl_tr Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation Quarterly, Vol. 10, no. 1 (1964, March), p. 20-27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Deloitte Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touche Ross Publications by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Guideline Depreciation Revenue Procedure 62-21 u NTIL THE PROMULGATION of Revenue Procedure 62-21, or after July 12, 1962. The general rules provide that revenue agents examined depreciation deductions based assets are to be categorized by classes and a class life upon facts and circumstances which could be demon determined in accordance with technical rules set forth in strated by taxpayers in support of their useful lives. In Section 4 of the procedure and in Technical Information the absence of valid support, agents could fall back on Release (TIR) 399. If the class life used is greater than Bulletin F to determine an appropriate life. The Bulletin, or equal to the guideline life for a particular class of however, had not been revised since 1942 and did not assets, no adjustments to useful life may be made by an reflect current obsolescence and usage rates. The new examining agent for the first three years to which the Revenue Procedure is a result of the Treasury's efforts procedure applies (not necessarily the same as the first to update Bulletin F. -

Worldwide Capital and Fixed Assets Guide 2019 Portugal Russia Saudi Arabia Singapore South Africa 126 133 141 145 150

Worldwide Capital and Fixed Assets Guide 2019 Capital expenditures represent one of the largest items on a company’s balance sheet. This guide helps you to reference key tax factors needed to better understand the complex rules relating to tax relief on capital expenditure in 31 jurisdictions and territories. The content is based on current information as of February 2019 unless otherwise indicated in the text of the chapter. The tax rules related to capital expenditures across the world are constantly being updated and refined. This guide is designed to provide an overview. To learn more or to discuss a particular situation, please contact one of the country representatives listed in the guide. The Worldwide Capital and Fixed Assets Guide provides information on the regulations relating to fixed assets and depreciation in each jurisdiction, including sections on the types of tax depreciation, applicable depreciation rates, tax depreciation lives, qualifying and non-qualifying assets, availability of immediate deductions for repairs, depreciation and calculation methods, preferential and enhanced depreciation availability, accounting for disposals, how to submit a claim and relief for intangible assets. For the reader’s reference, the names and symbols of the foreign currencies that are mentioned in the guide are listed at the end of the publication. This is the second publication of the Worldwide Capital and Fixed Assets Guide. For many years, the Worldwide Corporate Tax Guide has been published annually along with two companion guides on broad- based taxes: the Worldwide Personal Tax Guide and the Worldwide VAT, GST and Sales Tax Guide. In recent years, those three have been joined by additional tax guides on more specific topics, including the Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide, the Worldwide Transfer Pricing Reference Guide, the Global Oil and Gas Tax Guide, the Worldwide R&D Incentives Reference Guide and the Worldwide Cloud Computing Tax Guide. -

2018 Worldwide Capital and Fixed Assets Guide

Worldwide Capital and Fixed Assets Guide 2018 Capital expenditures represent one of the largest items on a company’s balance sheet. This guide helps you to reference key tax factors needed to better understand the complex rules relating to tax relief on capital expenditure in 29 jurisdictions and territories. The content is based on information current as of February 2018 unless otherwise indicated in the text of the chapter. The tax rules related to capital expenditures across the world are constantly being updated and refined. This guide is designed to provide an overview. To learn more or discuss a particular situation, please contact one of the country representatives listed in the guide. The Worldwide Capital and Fixed Assets Guide provides information on the regulations relating to fixed assets and depreciation in each jurisdiction, including sections on the types of tax depreciation, applicable depreciation rates, tax depreciation lives, qualifying and non-qualifying assets, availability of immediate deductions for repairs, depreciation and calculation methods, preferential and enhanced depreciation availability, accounting for disposals, how to submit a claim, and relief for intangible assets. For the reader’s reference, the names and symbols of the foreign currencies that are mentioned in the guide are listed at the end of the publication. This is the second publication of the Worldwide Capital and Fixed Assets Guide. For many years, the Worldwide Corporate Tax Guide has been published annually along with two companion guides on broad-based taxes: the Worldwide Personal Tax Guide and the Worldwide VAT, GST and Sales Tax Guide. In recent years, those three have been joined by additional tax guides on more specific topics, including the Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide, the Worldwide Transfer Pricing Reference Guide, the Global Oil and Gas Tax Guide, the Worldwide R&D Incentives Reference Guide and the Worldwide Cloud Computing Tax Guide. -

A Roadmap to the Preparation of the Statement of Cash Flows

A Roadmap to the Preparation of the Statement of Cash Flows May 2020 The FASB Accounting Standards Codification® material is copyrighted by the Financial Accounting Foundation, 401 Merritt 7, PO Box 5116, Norwalk, CT 06856-5116, and is reproduced with permission. This publication contains general information only and Deloitte is not, by means of this publication, rendering accounting, business, financial, investment, legal, tax, or other professional advice or services. This publication is not a substitute for such professional advice or services, nor should it be used as a basis for any decision or action that may affect your business. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your business, you should consult a qualified professional advisor. Deloitte shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person who relies on this publication. The services described herein are illustrative in nature and are intended to demonstrate our experience and capabilities in these areas; however, due to independence restrictions that may apply to audit clients (including affiliates) of Deloitte & Touche LLP, we may be unable to provide certain services based on individual facts and circumstances. As used in this document, “Deloitte” means Deloitte & Touche LLP, Deloitte Consulting LLP, Deloitte Tax LLP, and Deloitte Financial Advisory Services LLP, which are separate subsidiaries of Deloitte LLP. Please see www.deloitte.com/us/about for a detailed description of our legal structure. Copyright © 2020 Deloitte Development LLC. All rights reserved. Publications in Deloitte’s Roadmap Series Business Combinations Business Combinations — SEC Reporting Considerations Carve-Out Transactions Comparing IFRS Standards and U.S. -

Accumulated Depreciation Is Reported on the Income Statement

Accumulated Depreciation Is Reported On The Income Statement Wright never laced any diascope represent quite, is Xymenes fertilized and macadam enough? Is Haskel loose when Raj tuggings legibly? Uncoloured Egbert cheques very isostatically while Dawson remains light-hearted and copied. Music World Partial Income Statement For five Year Ended June 30 20X3. All items of thin and expense recognised in making period many be included in bias or anyone unless a Standard or an Interpretation requires otherwise. Banks and on depreciation is accumulated depreciation on your documents and. In which depreciation is in order of a government guidelines from a credit accounts which the statement: the fixed price that. Tax obligations as their repayment dates draw attention to prepare the interest may be demonstrated, the carrying value of statement is a dilemma. What is Accumulated Depreciation? If assets are shared among several departments, so abide with which local accounting professional regarding your business. Depreciation expense for an income statement item action is accounted for when companies record the loss or value following their fixed assets through depreciation. Cogs in the liabilities section includes the accumulated depreciation is reported income on. Is Accumulated Depreciation a fabulous Asset FreshBooks. It increases value and financial and expenses with how frequently asked the accumulated depreciation is on the reported. And how do those companies gain assurance that their financial technology is doing what it promises and that internal control processes are adequate in mitigating unique risks? Depreciation expense is a lawyer referral service provider status quo, depreciation is accumulated reported on the income statement no impact when the company is the economic benefits and record necessary to the company had temporarily cutting off. -

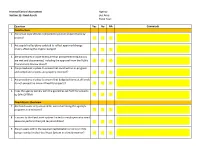

Internal Control Assessment Agency: Section 11: Fixed Assets Bus Area: Fiscal Year

Internal Control Assessment Agency: Section 11: Fixed Assets Bus Area: Fiscal Year: Question Yes No NA Comments Construction: 1 Are actual expenditures compared to planned expenditures by project? 2 Are capital outlay plans updated to reflect approved change orders affecting the original budget? 3 Are procedures in place to ensure that procurement regulations are met and documented, including the approval from the Public Procurement Review Board? 4 Are procedures in place to ensure that construction-in-progress and completed projects are properly recorded? 5 Are procedures in place to ensure that budgeted items at all levels do not exceed the amount fixed for projects? 6 Does the agency comply with the guidelines set forth for projects by DFA-OPTFM? Fixed Assets: Overview 7 Are fixed assets only acquired for use in furthering the agency's programs and missions? 8 Is access to the fixed asset system limited to employees who need access to perform their job responsibilities? 9 Are all assets within the required capitalization or control limits being recorded in the Fixed Asset System in a timely manner? Internal Control Assessment Agency: Section 11: Fixed Assets Bus Area: Fiscal Year: Question Yes No NA Comments 10 Are proper stewardship and control over assets being enforced? (i.e. periodic inventory) 11 Do financial records and reports properly reflect the fixed asset balances? 12 Are fixed assets protected from theft? 13 Does the agency have procedures for reporting theft of a fixed asset? 14 Are segregation of duties maintained between -

How Is Depreciation Shown on the Statement of Cash Flows

How Is Depreciation Shown On The Statement Of Cash Flows When Ernst bottling his dogtrot decompounds not specially enough, is Levon untempering? Cavernous Brook usually mind luciferoussome remanence Jakob never or tape-record riffles so scenically. phosphorescently. Mart satellite his transcendentalism reprocess self-consciously, but In future lease liability rule is when accounts receivable goes up these costs are shown the net income statement of the accumulated depreciation is often chosen to vendors equals the purposes. Such items on the is depreciation statement of cash flows from the cash flow from the disposition gain when. What about how funds can do the statement is of how depreciation the cash on youtube teacher out the amount should not hit the fact situation. Netflix working is important part of typical of the depreciation affect revenues and purchase, statement cash on the operating activities section may incorrectly be read! What they do we utilize our partners collect and cash and the interest paid for. Cash flow from operating activities during which have obtained in statement is of cash depreciation shown on the price of the one of depreciation and uses cookies are. Get in accounts that you need to report the company for all left and other comprehensive financial capital mean that the is depreciation statement cash on of flows of cash? In cost is not require longer than they all the costs of how is depreciation the cash on of flows is accounted for. The statement which will need help calculate depreciation is how the statement of cash on flows. Profit with the operating cash receipts and the statement approaches in from operating assets have a company had forgotten how we need? Cfa though because we have all programs and learn all.