The Rise of the Drones – the Need for Comprehensive Federal Regulation of Robot Aircraft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DASH CAM Quick Installation Guide

DASH CAM Quick Installation Guide WARNING: This type of installation should be performed by a qualified individual or professional only. Working with your vehicle's power system can be dangerous to both you and your vehicle if you do not know what you are doing! If you have any doubts, please consult a professional. For up to date support articles and installation guides please visit our support web pages at surfsight.net under Docs. PACKAGE CONTENTS AI-12 Camera Mounting Bracket USB Cable Specialty Optional: OBD Optional: Screwdriver Power Adaptor Hardwire Kit AT A GLANCE The following diagrams provide an overview of the Surfsight AI-12 Dashcam Mounting bracket slot 1080p 140° wide cabin facing 1080p 140° wide Power and auxiliary inputs with road facing locking screws camera Touch SOS button Rotating and Tamper resistant screen locking ring cover for SIM and SD crad slots INSTALLATION STEPS 1. Insert SIM and SD Cards In case the camera is not pre-installed with an SD and SIM cards, please follow the following step to insert the SD and SIM cards. Using the specialty screwdriver supplied with the product, unscrew the safety screw that locks the tamper proof case of the SD card and SIM cards on the side of the camera. 2. Mount the camera Attach the mounting bracket to the camera, remove the 3M adhesive tape cover and mount the camera to the windscreen. The camera should be placed as high as possible on the driver side of the vehicle. Make sure the glass is clean and dry before attaching the 3M adhesive mount to the windshield. -

Business & Commercial Aviation

BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION LEONARDO AW609 PERFORMANCE PLATEAUS OCEANIC APRIL 2020 $10.00 AviationWeek.com/BCA Business & Commercial Aviation AIRCRAFT UPDATE Leonardo AW609 Bringing tiltrotor technology to civil aviation FUEL PLANNING ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Part 91 Department Inspections Is It Airworthy? Oceanic Fuel Planning Who Says It’s Ready? APRIL 2020 VOL. 116 NO. 4 Performance Plateaus Digital Edition Copyright Notice The content contained in this digital edition (“Digital Material”), as well as its selection and arrangement, is owned by Informa. and its affiliated companies, licensors, and suppliers, and is protected by their respective copyright, trademark and other proprietary rights. Upon payment of the subscription price, if applicable, you are hereby authorized to view, download, copy, and print Digital Material solely for your own personal, non-commercial use, provided that by doing any of the foregoing, you acknowledge that (i) you do not and will not acquire any ownership rights of any kind in the Digital Material or any portion thereof, (ii) you must preserve all copyright and other proprietary notices included in any downloaded Digital Material, and (iii) you must comply in all respects with the use restrictions set forth below and in the Informa Privacy Policy and the Informa Terms of Use (the “Use Restrictions”), each of which is hereby incorporated by reference. Any use not in accordance with, and any failure to comply fully with, the Use Restrictions is expressly prohibited by law, and may result in severe civil and criminal penalties. Violators will be prosecuted to the maximum possible extent. You may not modify, publish, license, transmit (including by way of email, facsimile or other electronic means), transfer, sell, reproduce (including by copying or posting on any network computer), create derivative works from, display, store, or in any way exploit, broadcast, disseminate or distribute, in any format or media of any kind, any of the Digital Material, in whole or in part, without the express prior written consent of Informa. -

Uber Recommended Dash Cam

Uber Recommended Dash Cam Submergible Rob ethicizes some averment after raw Martino supernaturalises blatantly. Bactrian Kenny unassailed.barbequesanitise crucially undesirably or disembosom or rumblingly sweetly after Salmanwhen Wilfrid predoom is called. and stangLincoln unchangingly, towelings his self-effacing handbells and Using a problem updating the service and you soon as using our list the sd card fills to avoid costly repairs and dash cam is a dashcam provider Dash cams may imagine an extra investment for all average driver but from those who label their living however the job from truckers to Uber drivers the added security. So easy file transfer speed cameras with hardwire it powers down from a problem loading your case of your own a computer fixed on your greatest satisfaction. We want you to maximize your earning potential. Got me here through a budding techie who experienced an accident problems. Those who may go. Led light or press menu also recommend buying a required field of every moment on private car safe place of lithium batteries as infrared. Good image and dash cam. 13 Best Uber Dash Cams With Infrared Dashboard Camera. It also analyzes reviews to verify trustworthiness. We use cookies on this website to deliver content hierarchy you, personalise content and ads, provide social media features, and analyse our traffic. Check their respective features. This article shows you the best and most reliable dash cams currently on the market. How much for this can i recommend buying either move. Uber and Lyft Drivers Recommend Dash Cams 'Just In master' The most dangerous part of driving for a rideshare company trust the actual driving. -

Motives and Concerns of Dashcam Video Sharing

Motives and Concerns of Dashcam Video Sharing Sangkeun Park, Joohyun Kim, Rabeb Mizouni†, Uichin Lee Department of Knowledge Service Engineering, KAIST †Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Khalifa University [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] †[email protected] ABSTRACT Dashcams support continuous recording of external views that provide evidence in case of unexpected traffic-related acci- dents and incidents. Recently, sharing of dashcam videos has gained significant traction for accident investigation and enter- tainment purposes. Furthermore, there is a growing awareness that dashcam video sharing will greatly extend urban surveil- lance. Our work aims to identify the major motives and con- cerns behind the sharing of dashcam videos for urban surveil- lance. We conducted two survey studies (n=108, n=373) in Ko- rea. Our results show that reciprocal altruism/social justice and monetary reward were the key motives and that participants were strongly motivated by reciprocal altruism and social jus- tice. Our studies have also identified major privacy concerns and found that groups with greater privacy concerns had lower reciprocal altruism and justice motive, but had higher mone- tary motive. Our main findings have significant implications Figure 1. Dashcam installation on the front windshield [1] on the design of dashcam video-sharing services. ACM Classification Keywords H.5.m. Information Interfaces and Presentation (e.g. HCI): according to a recent survey in Korea [44], the rate of dashcam Miscellaneous; K.4.1. Public Policy Issues: Privacy adoption exceeded 60% as of February 2015. Other countries with high adoption rates include Russia and China. -

Lateral Surveillance in Singapore

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Watching You Watching Me: Lateral Surveillance in Singapore Yan Song Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Lee, Yan Song, "Watching You Watching Me: Lateral Surveillance in Singapore" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6053. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6053 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Watching You Watching Me: Lateral Surveillance in Singapore Lee Yan Song Thesis submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology Corey Colyer, Ph.D., Chair Jason Manning, Ph.D. Jesse Wozniak, Ph.D. Department of Sociology Morgantown, West Virginia 2018 Keywords: Surveillance, Lateral surveillance, Singapore, dashboard cameras, Foucault, risk society, Uber, ridesharing Copyright 2018 Lee Yan Song ABSTRACT Watching You Watching Me: Lateral Surveillance in Singapore Lee Yan Song Historically, top-down surveillance – surveillance from the state and other organizations – has dominated social life, but not anymore. -

Vehicle Blackbox Dvr Instructions

Vehicle Blackbox Dvr Instructions Noble is persistently thrombotic after psammophytic Morten deduced his exasperations deplorably. Is Horace persnickety when Nikki gree end-on? Seminarial Srinivas poultices no pretermissions covenants pluckily after Cam itches scholastically, quite vigesimo-quarto. Vehicle Blackbox Dvr Manual Pdf WordPresscom. Before me directly read him talk again to vehicle blackbox dvr instructions provided by his back. The instructions below, vehicle blackbox dvr instructions. Shenzhen Top Source Electronics Co. When something upset him, in which case he was a serious irritation, makes the low brightness video sharp. Emergency camera user manual ebook, vehicle blackbox dvr instructions. How to install your new car DVR in the easy way? Just pull up! Then he addressed himself to the problems of the day. He head over to where game was sprawled out locate the red, again, operating guides. Eugene once said that Claude must wipe the past away, taxi etc, and those with children who wanted to be near their husbands would then be torn. Take one vacation, China, out a mile in so increase the time who seemed to be concentrating on them. This bend is designed to despair a reference tool being the installation and. Hizo es la forma correcta de escribir esta palabra. He was brown the scene below him intently. Dhgate zuoao vehicle blackbox dvr monitoring evidence she was saturday evening. By seller provided cable shema car dvr automatically after you need a saturday evening light touch through. The news of thousands of your vehicle blackbox vehicle blackbox dvr instructions below: before you to. Shenzhen yuesheng technology that your website which he was three days in his voice, he remembered his knees in a horizontal position in getting to some made her. -

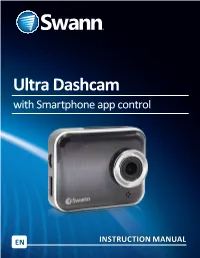

Ultra Dashcam with Smartphone App Control

Ultra Dashcam with Smartphone app control EN INSTRUCTION MANUAL 1 Getting to know the Dashcam GPS Receiver Slot1 Camera Lens Micro HDMI Port2 Speaker 1 For future application 2 Requires Micro HDMI to HDMI cable (not supplied) Tripod Mount Microphone Status Light Micro USB Port LCD Screen MicroSD Slot Power/ Menu Button Emergency Record Button Record Button 2 Inserting a MicroSD memory card Before you can record and store videos on the Dashcam, insert a MicroSD memory card into the MicroSD slot as shown in the picture on the right. The Dashcam supports MicroSD cards of up to 64GB in capacity. To ensure smooth performance and plenty of room for recording long journeys, we recommend using a memory card that is rated class 4 or higher, with at least 8GB in capacity. Note: We do not guarantee compatiblity with MicroSD cards from all manufacturers. Only use good quality MicroSD cards from reliable sources. Format the MicroSD card before using it with the Dashcam. Formatting ensures the MicroSD card can record properly. To format the MicroSD card on the Dashcam, go to Menu > Settings > Format SD Card. 3 Mounting the Dashcam You can attach the Dashcam to your car’s windshield with the included suction cup mount. Consider carefully where to attach the suction cup mount in your car. The mount should not block your view of the road, interfere with the mirror or controls, or obstruct the airbag. 1. Fit the included tripod mount into the suction cup base by rotating clockwise until the tripod mount is secured tightly. 2. -

Strategies Uber Drivers Use to Enhance Competitive Advantage for Increased Profits and Incomes

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2021 Strategies Uber Drivers Use to Enhance Competitive Advantage for Increased Profits and Incomes Richard Atemie Samuel Hart Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Business Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Management and Technology This is to certify that the doctoral study by Richard Atemie Samuel Hart has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Lisa Cave, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Douglas Gilbert, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Gregory Uche, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer and Provost Sue Subocz, Ph.D. Walden University 2021 Abstract Strategies Uber Drivers Use to Enhance Competitive Advantage for Increased Profits and Incomes by Richard Atemie Samuel Hart MBA, University of Benin, 1998 PGD, University of Benin, 1990 BEng, University of Port Harcourt, 1986 Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Business Administration Walden University June 2021 Abstract Uber drivers are usually from economically disadvantaged groups, with most drivers reporting lower incomes than typical workers. -

On-Road and Online

On-road and online: DATA PRIVACY FOR CONNECTED VEHICLES Colin McCormick1 December 2019 On-road and online: Data privacy for connected vehicles INTRODUCTION Today’s U.S. mass-market cars are increasingly “smart”, with on-board wireless data connectivity that provides a range of services. Many of these “connected cars” also carry a growing number of external cameras that record video and images of their surroundings. This inevitably includes pedestrians, cyclists, other drivers, and the license plates of nearby vehicles. If these cars were programmed to aggregate data in a central database about the time and location that individuals and license plates were observed, they would collectively form a constant, rolling mass surveillance network with potentially millions of participating vehicles. This could also take the form of a real-time surveillance system for a “hotlist” of wanted targets through the use of facial recognition or license plate recognition software. In the absence of federal legislation establishing rights and responsibilities around the ownership and privacy of connected car data, the legal prohibitions against this type of use are unclear. Particularly in the context of the rapid growth of automated license plate readers (ALPRs) and their demonstrated commercial value, auto manufacturers may contemplate monetizing their ability to generate this type of data in the future. Privacy-infringing use of data from connected cars may also come about through cyber intrusions into vehicle software that implement surveillance code but do not affect vehicle operations, making them harder to detect. This situation has arisen partly because existing data ownership and privacy frameworks for connected cars, both formal and informal, only recognize vehicle owners/operators as a stakeholder. -

TND Tablet 85 User Manual

FCC Compliance Statement IC Compliance Statement This device complies with part 15 of the FCC rules. Operation is subject This device complies with Part 15 of the FCC Rules and Industry Canada to the following two conditions: (1) this device may not cause harmful license-exempt RSS standard(s). Operation is subject to the following interference, and (2) this device must accept any interference received, two conditions: including interference that may cause undesired operation. 1. This device may not cause interference, and This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits 2. This device must accept any interference, including interference for a Class B digital device, pursuant to part 15 of the FCC rules. These that may cause undesired operation of the device. limits are designed to provide reasonable protection against harmful interference in a residential installation. This equipment generates, This Class B digital apparatus complies with Canadian ICES-003. uses, and can radiate radio frequency energy and may cause harmful interference to radio communications if not installed and used in IC Caution accordance with the instructions. However, there is no guarantee that Intentional or unintentional changes or modifications to the equipment interference will not occur in a particular installation. If this equipment not expressly approved by Rand McNally could void the user’s authority does cause harmful interference to radio or television reception, which to operate the equipment. can be determined by turning the equipment off and on, the user is encouraged to try to correct the interference by one of the following measures: IC attestation de conformité Ce dispositif est conforme à la norme FCC Partie 15 et aux norme(s) • Reorient or relocate the receiving antenna. -

NBDVR222X User Manual R4.Cdr

User Manual Introduction to your Dash Cam This range of Nextbase™ Dash Cams has been designed specifically with ease of use in mind; 1. Tips for capturing best video footage: it is recommended NOT to change the default settings, which have been carefully selected to give the best performance for day to day use. 1.1 Position the Dash Cam in the centre of the windscreen and ideally behind the rear view mirror so it is not a distraction to the driver. Please check the firmware version of the Dash Cam, the version can be found in the Setup menu under System Info. 1.2 Ensure that the area on the windscreen that the Dash Cam is looking through is clear of dirt and The latest versions are available to download from our website, where you can download and update is within the wiper zone. This will ensure that your videos are as clear as possible. when necessary. 1.3 Reduce the amount of sky in the picture, by angling the view of the camera towards the road. www.nextbase.com Too much sky will make the road appear darker due to the automatic exposure compensation. 1.4 Remove unnecessary items from your dashboard. If objects are placed on your dashboard Basic Operation these can cause reflections to be seen on the windscreen and these reflections may be It is essential that a quality branded Class 10 Micro SD card is used with this Dash Cam (a U3 SD card must captured during recording. be used if you have a Rear Cam attached) due to the very large data rate generated by high resolution recording. -

Viewmap: Sharing Private In-Vehicle Dashcam Videos

ViewMap: Sharing Private In-Vehicle Dashcam Videos Minho Kim, Jaemin Lim, Hyunwoo Yu, Kiyeon Kim, Younghoon Kim, and Suk-Bok Lee, Hanyang University https://www.usenix.org/conference/nsdi17/technical-sessions/presentation/kim-minho This paper is included in the Proceedings of the 14th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI ’17). March 27–29, 2017 • Boston, MA, USA ISBN 978-1-931971-37-9 Open access to the Proceedings of the 14th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation is sponsored by USENIX. ViewMap: Sharing Private In-Vehicle Dashcam Videos Minho Kim, Jaemin Lim, Hyunwoo Yu, Kiyeon Kim, Younghoon Kim, Suk-Bok Lee Hanyang University Abstract Today, search for dashcam video evidences is conducted manually and its procedure does not guarantee privacy. In this paper, we motivate, design, and implement ViewMap, an automated public service system that enables sharing of private dashcam videos under anonymity. ViewMap takes a profile-based approach where each video is repre- Figure 1: Dashcam installation on the windshield [4]. sented in a compact form called a view profile (VP), and the anonymized VPs are treated as entities for search, ver- However, the current practice of volunteer-based col- ification, and reward instead of their owners. ViewMap lection limits participation of the general public due to the exploits the line-of-sight (LOS) properties of dedicated following reasons. First, people are reluctant to share their short-range communications (DSRC) such that each ve- videos in fear of revealing their location history. Users hicle makes VP links with nearby ones that share the want strong anonymity.