Spignesi, Sinatra, and the Pittsburgh Steelers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Franco Harris President, Super Bakery Former Steeler & Pro Football Hall

Franco Harris President, Super Bakery Former Steeler & Pro Football Hall of Famer Franco Harris is well known for his outstanding career in the National Football League, one so productive that it earned him a 1990 induction into The Pro Football Hall of Fame. He also was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2011. During his years with the Pittsburgh Steelers, Harris set the standard for NFL running backs - big, fast and agile with explosive cutback ability. He established many team and league records, played in nine Pro Bowls, and led the Steelers’ charge to four Super Bowl victories. Franco was named MVP of Super Bowl IX. His “Immaculate Reception” in the final seconds of the 1972 AFC playoff game against the Oakland Raiders is considered to be the greatest individual play in NFL history. After football, Harris applied himself to his college degree in Food Service and Administration. He started out in the early 1980’s with a small distribution company called Franco’s All Naturèl, focusing on high quality, natural products. This is where and how Harris learned the business, driving thousands of miles, meeting with potential customers, c-store chains and distributors. He warehoused, sold, promoted and sometimes even delivered Franco’s FROZEFRUIT and his other all-natural products. In 1990 Harris established Super Bakery with the goal of making it The Leader in Bakery Nutrition. Super Donuts and Super Buns are made with no artificial flavors, colors, or preservatives and are fortified with NutriDough, a special dough of Minerals, Vitamins and Protein. Super Donuts and Super Buns are sold to school systems across America, providing MVP Nutrition! to millions of students each year. -

Photo Courtesy of the Pittsburgh Steelers

Photo Courtesy of the Pittsburgh Steelers 1 IMCD is a global leader in the sales, marketing and distribution of specialty chemicals and ingredients for the Industrial and Life Science markets, delivering innovative solutions that exceed customer expectations. Representing market leading global chemical companies enables us to offer a comprehensive and complementary product portfolio. We bring added value and growth to both our customers and principal partners across the world through our technical, marketing and supply chain expertise. With over 1800 high-caliber professionals in more than 40 countries on 6 continents, IMCD offers a unique combination of local understanding backed by an impressive International infrastructure. To find out how our expertise can bring value to your business, please visit www.imcdus.com 2 Welcome to Pittsburgh Chemical Day 2 017 On behalf of the Joint Chemical Group of Pittsburgh and our volunteer planning committee, we welcome you to the 50th annual Pittsburgh Chemical Day conference. This year we are celebrating 50 years of coming together to network, learn, and grow in an ever-changing Chemical Industry. We have designed our program to highlight the past while IMCD is a global leader in the sales, marketing and distribution looking towards the future markets, trends, and regulations that of specialty chemicals and ingredients for the Industrial and Life will impact us in the years to come. Science markets, delivering innovative solutions that exceed customer expectations. Representing market leading global Our goal is to utilize our new venue, Heinz Field, to help chemical companies enables us to offer a comprehensive and celebrate our incredible history and city, while providing you an complementary product portfolio. -

1.) What Was the Original Name of the Pittsburgh Steelers? B. the Pirates

1.) What was the original name of the Pittsburgh Steelers? B. The Pirates The Pittsburgh football franchise was founded by Art Rooney on July 7, 1933. When he chose the name for his team, he followed the customary practice around the National Football League of naming the football team the same as the baseball team if there was already a baseball team established in the city. So the professional football team was originally called the Pittsburgh Pirates. 2.) How many Pittsburgh Steelers have had their picture on a Wheaties Box? C. 13 Since Wheaties boxes have started featuring professional athletes and other famous people, 13 Steelers have had their pictures on the box. These players are Kevin Greene, Greg Lloyd, Neil O'Donnell, Yancey Thigpen, Bam Morris, Franco Harris, Joe Greene, Terry Bradshaw, Barry Foster, Merril Hoge, Carnell Lake, Bobby Layne, and Rod Woodson. 3.) How did sportscaster Curt Gowdy refer to the Immaculate Reception, which happened two days before Christmas? Watch video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GMuUBZ_DAeM A. The Miracle of All Miracles “You talk about Christmas miracles. Here's the miracle of all miracles. Watch this one now. Bradshaw is lucky to even get rid of the ball! He shoots it out. Jack Tatum deflects it right into the hands of Harris. And he sets off. And the big 230-pound rookie slipped away from Warren and scored.” —Sportscaster Curt Gowdy, describing an instant replay of the play on NBC 4.) URA Acting Executive Director Robert Rubinstein holds what football record at Churchill Area High School? B. -

A CHRONOLOGY of PRO FOOTBALL on TELEVISION: Part 2

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 26, No. 4 (2004) A CHRONOLOGY OF PRO FOOTBALL ON TELEVISION: Part 2 by Tim Brulia 1970: The merger takes effect. The NFL signs a massive four year $142 million deal with all three networks: The breakdown as follows: CBS: All Sunday NFC games. Interconference games on Sunday: If NFC team plays at AFC team (example: Philadelphia at Pittsburgh), CBS has rights. CBS has one Thanksgiving Day game. CBS has one game each of late season Saturday game. CBS has both NFC divisional playoff games. CBS has the NFC Championship game. CBS has Super Bowl VI and Super Bowl VIII. CBS has the 1970 and 1972 Pro Bowl. The Playoff Bowl ceases. CBS 15th season of NFL coverage. NBC: All Sunday AFC games. Interconference games on Sunday. If AFC team plays at NFC team (example: Pittsburgh at Philadelphia), NBC has rights. NBC has one Thanksgiving Day game. NBC has both AFC divisional playoff games. NBC has the AFC Championship game. NBC has Super Bowl V and Super Bowl VII. NBC has the 1971 and 1973 Pro Bowl. NBC 6th season of AFL/AFC coverage, 20th season with some form of pro football coverage. ABC: Has 13 Monday Night games. Do not have a game on last week of regular season. No restrictions on conference games (e.g. will do NFC, AFC, and interconference games). ABC’s first pro football coverage since 1964, first with NFL since 1959. Main commentary crews: CBS: Ray Scott and Pat Summerall NBC: Curt Gowdy and Kyle Rote ABC: Keith Jackson, Don Meredith and Howard Cosell. -

2013 Steelers Media Guide 5

history Steelers History The fifth-oldest franchise in the NFL, the Steelers were founded leading contributors to civic affairs. Among his community ac- on July 8, 1933, by Arthur Joseph Rooney. Originally named the tivities, Dan Rooney is a board member for The American Ireland Pittsburgh Pirates, they were a member of the Eastern Division of Fund, The Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation and The the 10-team NFL. The other four current NFL teams in existence at Heinz History Center. that time were the Chicago (Arizona) Cardinals, Green Bay Packers, MEDIA INFORMATION Dan Rooney has been a member of several NFL committees over Chicago Bears and New York Giants. the past 30-plus years. He has served on the board of directors for One of the great pioneers of the sports world, Art Rooney passed the NFL Trust Fund, NFL Films and the Scheduling Committee. He was away on August 25, 1988, following a stroke at the age of 87. “The appointed chairman of the Expansion Committee in 1973, which Chief”, as he was affectionately known, is enshrined in the Pro Football considered new franchise locations and directed the addition of Hall of Fame and is remembered as one of Pittsburgh’s great people. Seattle and Tampa Bay as expansion teams in 1976. Born on January 27, 1901, in Coultersville, Pa., Art Rooney was In 1976, Rooney was also named chairman of the Negotiating the oldest of Daniel and Margaret Rooney’s nine children. He grew Committee, and in 1982 he contributed to the negotiations for up in Old Allegheny, now known as Pittsburgh’s North Side, and the Collective Bargaining Agreement for the NFL and the Players’ until his death he lived on the North Side, just a short distance Association. -

Super Bowl X Pittsburgh 21, Dallas 17

P i t t S b u r g h MEDIA Super Bowl X Pittsburgh 21, Dallas 17 January 18, 1976 80,197 information Defense continued to dominate in the scoreless third quar- ter. Pittsburgh sacked Staubach seven times during the game and forced him to scramble on numerous occasions. Moreover, they pressured him into an uncharacteristic 3 interceptions. Once of the interceptions set up another field-goal try by Ge- rela, but he pulled it left from 33 yards. Dallas safety Cliff Harris mockingly patted him on the helmet, only to be unceremoni- MiaMi — What were, at the time, the two most popular teams F in the NFL met in Super Bowl X, and the contrast between ously dumped on his hip pads by irate Pittsburgh linebacker ootball their styles was as great as the hue of their jerseys. Jack Lambert. The inspired Steelers dominated after that. The glitzy, white-clad Dallas Cowboys—”America’s In the fourth quarter, Steelers reserve fullback Reggie Harrison Team”—combined a high-tech offense and a state-of-the- blocked Mitch Hoopes’s punt. The ball rolled through the end zone art Flex Defense to put on a dazzling show each Sunday. for a safety to cut the Cowboys’ lead to 10-9. Gerela, who’d donned S They were easy to like, and for once, they even had some- a corset to protect his ribs, regained his kicking touch with field TAFF thing of an underdog aura, having reached the Super Bowl goals of 36 and 18 yards to put the Steelers in front 15-10. -

Pittsburgh Steelers (3-2-1) Cleveland Browns (2-4-1)

PITTSBURGH STEELERS COMMUNICATIONS Burt Lauten - Director of Communications Dominick Rinelli - Public Relations/Media Manager PITTSBURGH STEELERS Angela Tegnelia - Public Relations Assistant 3400 South Water Street • Pittsburgh, PA 15203 412-432-7820 • Fax: 412-432-7878 www.steelers.com PITTSBURGH STEELERS (3-2-1) vs. CLEVELAND BROWNS (2-4-1) Sunday, Oct. 28, 2018 • 1 p.m. (ET) • Heinz Field • Pittsburgh, Pa. REGULAR SEASON GAME #7 PITTSBURGH STEELERS Pittsburgh Steelers (3-2-1) 2018 SCHEDULE vs. PRESEASON (3-1) Cleveland Browns (2-4-1) Thursday, Aug. 9 @ Philadelphia W, 31-14 (KDKA) Thursday, Aug. 16 @ Green Bay L, 51-34 (KDKA) DATE: Sunday, Oct. 28, 2018 | KICKOFF: 1 p.m. ET Saturday, Aug. 25 TENNESSEE W, 16-6 (KDKA/NFL Network) SITE: Heinz Field (68,400) • Pittsburgh, Pa. Thursday, Aug. 30 CAROLINA W, 39-24 (KDKA) PLAYING SURFACE: Natural Grass TV COVERAGE: CBS (locally KDKA-TV, channel 2) REGULAR SEASON (3-2-1) ANNOUNCERS: Ian Eagle (play-by-play) Sunday, Sept. 9 @ Cleveland T, 21-21 OT (CBS) Dan Fouts (analyst) | Evan Washburn (sideline) Sunday, Sept. 16 KANSAS CITY L, 42-37 (CBS) Monday, Sept. 24 @ Tampa Bay W, 30-27 (ESPN) LOCAL RADIO: Steelers Radio Network Sunday, Sept. 30 BALTIMORE L, 26-14 (NBC) WDVE-FM (102.5)/WBGG-AM (970) Sunday, Oct. 7 ATLANTA W, 41-17 (FOX) ANNOUNCERS: Bill Hillgrove (play-by-play) Sunday, Oct. 14 @ Cincinnati W, 28-21 (CBS) Tunch Ilkin (analyst) | Craig Wolfl ey (sideline) Sunday, Oct. 21 BYE WEEK Sunday, Oct. 28 CLEVELAND 1 p.m. (CBS) A LOOK AT THE COACHES Sunday, Nov. -

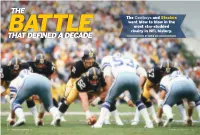

That Defined a Decade by David Lee Getty Images

THE The Cowboys and Steelers went blow to blow in the most star-studded BATTLE rivalry in NFL history. THAT DEFINED A DECADE BY DAVID LEE GETTY IMAGES 80 • VINTAGE COLLECTOR 24 VINTAGE COLLECTOR 24 • 81 #12. LYNN SWANN’S he Cleveland Browns dominated the NFL in the 1940s and ’50s. The CIRCUS CATCH Green Bay Packers bullied the league through the ’60s. But after the The 12th greatest play on the list hap- AFL and NFL finally merged, the 1970s was a decade of struggle between pened just two games after the Hail Mary the Dallas Cowboys and Pittsburgh Steelers that wouldn’t be settled in Super Bowl X between the Cowboys until January 1979. and Steelers. It was a clash of north vs. south, NFC vs. AFC, Noll vs. Landry, Bradshaw vs. Staubach, the Hail “It was a mistake,” Lynn Swann said on TMary and The Immaculate Reception. the NFL Films presentation of the play’s Through the decade, Dallas won 105 regular-season games and 14 postseason games. The Steelers won 99 in the ranking. “Obviously Mark Washington regular season and 14 in the postseason. The Steelers made it to the AFC Championship Game six times and went 4-0 tipped the ball away. If I actually caught it in Super Bowls. The Cowboys reached the NFC Championship Game seven times and were 2-3 in Super Bowls. without it being tipped, I might have run it Of the 48 total players selected to the NFL’s 1970s All-Decade Team, 14 are Cowboys or Steelers—nearly one- into the end zone for a touchdown.” third of the list. -

FIELD GOAL KICKIN' – the 1976 Oakland Raiders

FIELD GOAL KICKIN’ – The 1976 Oakland Raiders By Dean Gearhart 3/2/15 During the last episode, I noted that in the 1977 Topps football card set, one of the few teams that did not have a kicker represented in the set was the defending champion Oakland Raiders. I fast-forwarded to my 1978 set. Ah, there he is…… Errol Mann. Turning Errol’s card to the back, I see that he was, in fact, the Raiders kicker on their championship team. I also saw that he has a pilot’s license…..very nice…..and in 1976 he connected for 26 Extra points for Oakland……. …….and 4 field goals…… (record scratching sound effect)……4 field goals? Do what? I quickly turned to pro-football-reference.com to check the stats for the 1976 Oakland Raiders and it turns out that Errol took over for an injured Fred Steinfort. Well, that makes sense then. Steinfort had made 4 field goals of his own before getting injured, making for a grand total of……uh……8 field goals…….for the world champion Raiders. Really? When one thinks of the 1976 Raiders many images come to mind. They were led by quarterback Kenny “The Snake” Stabler and coached by the legendary John Madden. Their defense included Ted Hendricks (“The Stork”), John Matuszak (“The Tooz”), Skip Thomas (“Dr. Death”) and Jack Tatum (“The Assassin”). They finished the regular season a dominant 13-1-0, with a Week 4 blowout loss at New England the only blemish on their record. As fortune would have it, the Raiders would get a chance to avenge that lone defeat when they hosted New England in the first round of the AFC playoffs. -

S2 045-062-Super Bowl Sums.Qxd:E519-533-Super Bowl Sums.Qxd

SUPER BOWL STANDINGS/MVP SUPER BOWL COMPOSITE STANDINGS PETE ROZELLE TROPHY/SUPER BOWL MVPs* W L Pct. Pts. OP Super Bowl I — QB Bart Starr, Green Bay Baltimore Ravens 2 0 1.000 68 38 Super Bowl II — QB Bart Starr, Green Bay New Orleans Saints 1 0 1.000 31 17 Super Bowl III — QB Joe Namath, N.Y. Jets New York Jets 1 0 1.000 16 7 Super Bowl IV — QB Len Dawson, Kansas City Tampa Bay Buccaneers 1 0 1.000 48 21 Super Bowl V — LB Chuck Howley, Dallas San Francisco 49ers 5 1 .833 219 123 Super Bowl VI — QB Roger Staubach, Dallas Green Bay Packers 4 1 .800 158 101 Super Bowl VII — S Jake Scott, Miami New York Giants 4 1 .800 104 104 Super Bowl VIII — RB Larry Csonka, Miami Pittsburgh Steelers 6 2 .750 193 164 Super Bowl IX — RB Franco Harris, Pittsburgh Dallas Cowboys 5 3 .625 221 132 Super Bowl X — WR Lynn Swann, Pittsburgh Oakland/L.A. Raiders 3 2 .600 132 114 Super Bowl XI — WR Fred Biletnikoff, Oakland Washington Redskins 3 2 .600 122 103 Super Bowl XII — DT Randy White and Indianapolis/Baltimore Colts 2 2 .500 69 77 DE Harvey Martin, Dallas Chicago Bears 1 1 .500 63 39 Super Bowl XIII — QB Terry Bradshaw, Pittsburgh Kansas City Chiefs 1 1 .500 33 42 Super Bowl XIV — QB Terry Bradshaw, Pittsburgh New England Patriots 3 4 .429 138 186 Super Bowl XV — QB Jim Plunkett, Oakland Miami Dolphins 2 3 .400 74 103 Super Bowl XVI — QB Joe Montana, San Francisco Denver Broncos 2 4 .333 115 206 Super Bowl XVII — RB John Riggins, Washington St. -

Pittsburgh Steelers Game Release Week 13 Washington Football Team

WEEK 13 - STEELERS VS. WASHINGTON | 1 PITTSBURGH STEELERS COMMUNICATIONS Burt Lauten - Director of Communications Michael Bertsch - Communications Manager Angela Tegnelia - Communications Coordinator PITTSBURGH STEELERS Alissa Cavaretta - Communications Assistant/Social Media 3400 South Water Street • Pittsburgh, PA 15203 Thomas Chapman - Communications Intern 412-432-7820 • Fax: 412-432-7878 PITTSBURGH STEELERS GAME RELEASE WEEK 13 WASHINGTON FOOTBALL TEAM GAME INFORMATION 2020 REGULAR SCHEDULE (11-0) Monday, December 7 Heinz Field Day Date Opponent Location TV Time/Result 5 p.m. ET Pittsburgh, PA Mon. Sept. 14 New York Giants MetLife Stadium W, 26-16 Capacity 68,400 // Natural Grass Sun. Sept. 20 Denver Heinz Field W, 26-21 FOX Kevin Burkhardt (play-by-play) Locally WPGH-TV Daryl Johnston (analysis) Sun. Sept. 27 Houston Heinz Field W, 28-21 Pam Oliver (field reporter) Sun. Oct. 4 BYE WEEK* Steelers Radio Network (48 affiliates) Bill Hillgrove (play-by-play) Sun. Oct. 11 Philadelphia Heinz Field W, 39-28 102.5 WDVE-FM (Pittsburgh) Tunch Ilkin (analysis) Sun. Oct. 18 Cleveland Heinz Field W, 38-7 970 WBGG-AM (Pittsburgh) Craig Wolfley (analysis) Missi Matthews (field reporter) Sun. Oct. 25 Tennessee* Nissan Stadium W, 27-24 THE SERIES Sun. Nov. 1 Baltimore* M&T Bank Stadium W, 28-24 All-Time Washington leads, 42-33-3 Last: Steelers Win, 38-16 (Sept. 12, 2016) Sun. Nov. 8 Dallas AT&T Stadium W, 24-19 Home Washington leads, 22-20 Last: Steelers Win, 27-12 (Oct. 28, 2012) Sun. Nov. 15 Cincinnati Heinz Field W, 36-10 Away Washington leads, 20-13-3 Last: Steelers Win, 38-16 (Sept. -

Pittsburgh Steelers Game Release Week 15 Cincinnati Bengals

WEEK 15 - BENGALS VS. STEELERS | 1 PITTSBURGH STEELERS 3400 South Water Street • Pittsburgh, PA 15203 412-432-7820 • Fax: 412-432-7878 PITTSBURGH STEELERS GAME RELEASE WEEK 15 CINCINNATI BENGALS GAME INFORMATION 2020 REGULAR SCHEDULE (11-2) Monday, December 21 Paul Brown Stadium Day Date Opponent Location TV Time/Result 8:15 p.m. ET Cincinnati, OH (65,535) Mon. Sept. 14 New York Giants MetLife Stadium W, 26-16 ESPN Steve Levy (play-by-play) Sun. Sept. 20 Denver Heinz Field W, 26-21 Locally WTAE-TV Brian Griese (analysis) Louis Riddick (analysis) Sun. Sept. 27 Houston Heinz Field W, 28-21 Lisa Salters (field reporter) Sun. Oct. 4 BYE WEEK* Steelers Radio Network (48 affiliates) Bill Hillgrove (play-by-play) Sun. Oct. 11 Philadelphia Heinz Field W, 39-28 102.5 WDVE-FM (Pittsburgh) Tunch Ilkin (analysis) Sun. Oct. 18 Cleveland Heinz Field W, 38-7 970 WBGG-AM (Pittsburgh) Craig Wolfley (analysis) Missi Matthews (field reporter) Sun. Oct. 25 Tennessee* Nissan Stadium W, 27-24 THE SERIES Sun. Nov. 1 Baltimore* M&T Bank Stadium W, 28-24 All-Time Steelers lead, 67-35 Last: Steelers Win, 36-10 (Nov. 15, 2020) Sun. Nov. 8 Dallas AT&T Stadium W, 24-19 Home Steelers lead, 35-16 Last: Steelers Win, 36-10 (Nov. 15, 2020) Sun. Nov. 15 Cincinnati Heinz Field W, 36-10 Away Steelers lead, 32-19 Last: Steelers Win, 16-10 (Nov. 24, 2019) Sun. Nov. 22 Jacksonville EverBank Field W, 27-3 THE COACHES Wed. Dec. 2 Baltimore# Heinz Field W, 19-14 Mon.