Slinke Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postgraduate Research Symposium Programme 23 June 2021

[Type here] School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences Postgraduate Research Symposium Programme 23 June 2021 Organising Committe Agenda MS Teams Live Event 1 You can join Live Event 1 here. Time Speaker Title Professor Sebastien Ourselin Introduction Head of the School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, King's and College London Welcome 13:00 – 13:05 – 13:05 13:00 Dr Samantha Terry Senior Lecturer in Radiobiology, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, King's College London Ines Costa PhD student, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, King's Public Engagement College London 13:05 – 13:15 – 13:15 13:05 Aishwarya Mishra PhD student, Centre for Doctoral Training (CDT) in Smart Medical Imaging, King's College London and Imperial College London Dr Valentina Vitiello Professional Services Deputy Representative for the School DDI Committee; Diversity and Bullying Specialist Technical Operations Manager, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, King's College London 13:15 – 13:25 13:25 – 13:15 Dr Stamatia Giannarou Royal Society University Research Fellow and Lecturer in Surgical Cancer Keynote Speaker Technology and Imaging at the Hamlyn Centre for Robotic Surgery, Department of Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College London Cognitive Vision in Robotic Surgery 13:25 – 14:05 – 14:05 13:25 Please refer to page 7 for further details. Student Please refer to page 4 for details. Three-Minute Thesis Presentations 14:05 – 14:35 – 14:35 14:05 Student Please refer to pages 5-6 for details. 1-Minute Poster Pitches 14:35 – 15:00 15:00 – 14:35 1 Poster Sessions The poster sessions will be taking place in two streams on the Wonder.me platform. -

Msc Management

Programme Specification (Master’s Level) MSc Management This document provides a definitive record of the main features of the programme and the learning outcomes that a typical student may reasonably be expected to achieve and demonstrate if s/he takes full advantage of the learning opportunities provided. This programme specification is intended as a reference point for prospective students, current students, external examiners and academic and support staff involved in delivering the programme and enabling student development and achievement. Programme Information Programme Title Management Award(s) MSc Programme Code N1UF Awarding Institution Imperial College London Teaching Institution Imperial College London Faculty Imperial College Business School Department Imperial College Business School Mode and Period of Study 1 calendar year full-time (12 months) Cohort Entry Points Annually in September Relevant QAA Benchmark Statement(s) and/or Master’s Degrees in Business and Management other external reference points Total Credits ECTS: 90 CATS: 180 FHEQ Level Level 7 EHEA Level 2nd cycle External Accreditor(s) AMBA, EQUIS, AACSB International Specification Details Student cohorts covered by specification 2016/17 entry Person responsible for the specification Veronica Russell, Teaching & Quality Manager Date of introduction of programme October 2005 Date of programme specification/revision September 2016 Page 1 of 11 Description of Programme Contents The MSc in Management is offered over 12 months full-time. The programme content reflects the contemporary and relevant management skills necessary for managing in turbulent environments. In particular the programme will equip the participants with conceptual and practical skills, and enable them to analyse and solve challenging problems. The programme combines academic rigour and practical relevance. -

Lead Bioinformatician JD (1).Pdf

Job Description Job Title: Lead Bioinformatician Department/Division/Faculty: Epidemiology and Biostatistics/ Public Health/Medicine Campus location: St Mary’s Job Family/Level: Professional Services, Level 5 Responsible to: HDR UK Imperial site Director Line Management responsibility Junior bioinformatician for: Key Working Relationships Non-academia, academia and industrial partners within the HDR UK (internal): site, including HDR UK Fellows; Research Computing Services team, BRC ITMAT Data Science Group, Data Science Institute. Key Working Relationships HDR UK sites (including London sites – UCL, Kings College London, (external): London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Queen Mary University of London) Contract type: Full Time and Fixed term until 31 May 2023 Purpose of the Post HDR UK Health Data Research (HDR) UK is the new national institute for data science for health, which is being established in 2018 with long term funding support from research councils, UKRI, charitable and governmental research funders. The HDR UK seeks to drive improvements in the health of patients and populations through research at regional and national scale. The triple mission of HDR UK spans discovery of disease mechanisms in science through • Precision medicine and trials to public health; • Establishing platforms and underlying infrastructure to enable research at national scale; • Developing training and capacity opportunities. To deliver this mission, the five major London universities – UCL (coordinating), Imperial College London, King’s College London, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Queen Mary University of London – came together as a pan London Site. The terms of this partnership are set out in the Site Agreement. The six HDR UK Sites include London, Cambridge University (the Sanger and European Bioinformatics Institute), Oxford, the Midlands, Scotland and Wales/ Northern Ireland. -

Analysis of Research and Education Indicators to Support Designation of Academic Health Science Centres in England

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and EDUCATION AND THE ARTS decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public INFRASTRUCTURE AND service of the RAND Corporation. TRANSPORTATION INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND TERRORISM AND Browse Reports & Bookstore HOMELAND SECURITY Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Europe View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Errata To: Recipients of RR-318-DH, Analysis of research and education indicators to support designation of Academic Health Science Centres in England From: RAND Corporation Publications Department Date: May 2013 Re: Corrected pages (pp. -

£86.8 Billion for the UK Economy

Russell Group universities generate £86.8 billion for the UK economy Equivalent to the total UK-wide expenditure on the NHS for eight months The economic impact of Russell Group universities Analysis undertaken by London Economics • 261,000 jobs supported by Russell Group shows that each year teaching and universities directly and indirectly learning, research and knowledge transfer, education exports and the wider supply • 9:1 For every £1 of public research funding, Russell Group universities deliver an average chain of the 24 Russell Group universities return of £9 to the UK economy add £86.8 billion to the UK economy. This is just a snapshot of the economic • 7 non-UK undergraduate students contribution generated by our universities’ at a Russell Group university generate £1 million for the UK economy activities in the year 2015/16. Similar impacts will be created each year. • £177,000 impact per graduate Russell Group universities are anchor Graduates completing a full-time institutions in their local economies. undergraduate degree at a Russell Group university can typically expect to earn an They are found in every region and nation additional £88,000 over their working lives, of the UK, so the economic impact they with benefits to the public purse of an generate is spread right across the extra £89,000 whole country. The £86.8 billion contribution that Russell Group universities make to the UK economy comprises four elements: £20.7 billion delivered through the enhanced skills, productivity and earnings of the 166,000 UK-domiciled -

Links Between German U15 and Russell Group Universities

Links between German U15 and Russell Group universities More than 73,383 scientific publications were co-authored between academics in the UK and Germany between 2013 and 2017. Of these, 19,325 publications (26%) were between academics at Russell Group and German U15 universities, with over 30% growth in the number of co-authored publications between our two groups from 2013 to 2017.1 The average field-weighted citation impact (FWCI) of research carried out in the UK is 1.58 and for research carried out in Germany it is 1.43. However, when our academics work together, the FWCI of their joint scientific publications is 2.95. Collaborations between Russell Group and German U15 researchers deliver an even more enhanced impact of 3.70. The UK and Germany work together more than they work with any other countries in Horizon 2020 (the EU’s multi-annual research and innovation programme). Russell Group and German U15 universities have made over 400 collaborative links funded by Horizon 2020 since the programme began in 2014. A third of German U15’s Horizon 2020 projects include a Russell Group university partner. 2,250 students from Russell Group universities studied or worked in Germany as part of the EU’s Erasmus programme in 2015/16. About the Russell Group The Russell Group represents 24 leading UK universities committed to maintaining the very best research, an outstanding teaching and learning experience and unrivalled links with business and the public sector. Russell Group universities attract and welcome talented staff and students from across the globe and these individuals make a vital contribution to our academic and economic life. -

Qlikview Printing

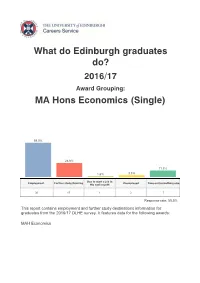

What do Edinburgh graduates do? 2016/17 Award Grouping: MA Hons Economics (Single) 59.0% 24.6% 11.5% 1.6% 3.3% Due to start a job in Employment Further study/training Unemployed Time out/something else the next month 36 15 1 2 7 Response rate: 55.5% This report contains employment and further study destinations information for graduates from the 2016/17 DLHE survey. It features data for the following awards: MAH Economics Employment Job Title Employer Name Place of Work Number Manager Lloyds Banking Group Cardiff 1 Analysis and Business RBS Edinburgh 1 Solutions Data Science Consultant Ekimetrics London 1 Maths Teacher A secondary school London 1 Hess International English Teacher Taipei 1 Education Group Accountant Wellers London 1 Associate PwC London 1 Associate Auditor EY Edinburgh 1 Auditor RSM Glasgow 1 Business Analyst Amazon London 1 Business Analyst McKinsey London 1 Bank Officer RBS London 1 Norwegian Ministry of Consultant Oslo 1 Health Economist Scottish Government Edinburgh 1 Institute for Fiscal Research Economist London 1 Studies Job Title Employer Name Place of Work Number Analyst BCG Edinburgh 1 Hermes Investment Analyst London 1 Management Analyst Jefferies London 1 Associate Consultant OC&C Strategy London 1 Financial Analyst JP Morgan London 1 Financial Analyst Piper Jaffray Aberdeen 1 Financial Analyst RBS London 1 Financial Consultant EY London 1 Financial Intern The Orb Group Glasgow 1 Shanghai Creation Investment Manager Shanghai 1 Investment Wealth Analyst Mercer London 1 Tax Consultant KPMG Birmingham 1 Data -

![ESIS-TC4 [Compatibility Mode]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8294/esis-tc4-compatibility-mode-1448294.webp)

ESIS-TC4 [Compatibility Mode]

ESIS 2008 Imperial College 5th International conference on the Fracture of Polymers, Kingston University Composites and Adhesives London September 2008, London les Diablerets, Switzerland Crashworthiness of Composite Thin-walled GFRP and CFRP Boxes H. Ghasemnejad a, B.R.K. Blackman b, H. Hadavinia a a Faculty of Engineering, Kingston University, Roehampton Vale, London SW15 3DW b Department of Mechanical Engineering, Imperial College London, Exhibition Road, London SW7 2BX, UK 1. INTRODUCTION 5. PROGRESSIVE CRUSHING OF GFRP COMPOSITE BOX Frond bending due to delamination between plies makes a considerable contribution to The combination of two distinct crushing modes of transverse shearing, and lamina bending which is called brittle fracture was the specific energy absorption (SEA) of composite box in crushing process. The crack observed for all laminate designs of GFRP composite boxes. propagation at the middle of the side walls of composite box are in Mode-I interlaminar fracture. In this regard the effect of fibre orientation and stacking sequence on the composite crash box design is sought by studying the effect of these on the interlaminar fracture toughness. In order to achieve this, glass fibre/epoxy orientations of [±60]10 , [02,±45]5, [0,90]10 and [0,90]5S and carbon/epoxy twill-weave fabrics of [0]4, [45]4 and [0,45]2 were studied experimentally. 2. EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES The fabrication of each DCB sample and composite box was laid-up with the same (a) [0,90] 10 (b) [0,90] 5S (c) [0 2,±45] 5 (d) [ ±60] fibre orientation. The mid-plane interfaces of GFRP DCB samples were 0/90, 90/90, 10 0/45 and +60/-60 and CFRP DCB samples were 0/0, 45/45 and 0/45 to determine the Plane view of crushed GFRP composite box, a) [0,90]10 , b) [0,90] 5S , c) [0 2,±45] 5, d) [ ±60] 10. -

Tuan Vu Updated 2020

Tuan Vu updated 2020 Imperial College London, UK Email: [email protected]; Tel: +44 012141 47297 https://www.imperial.ac.uk/people/tuan.vu or https://github.com/tuanvvu/ Employment Senior air quality scientist, Imperial College London, UK, 2020-onwards Senior air quality scientist, King’s College London, UK, 2019-2020 Research fellow, University of Birmingham, UK, 2016- 2019 Marie Curie early researcher, University of Birmingham, UK, 2013-16 Quality production leader, Decathlon Co, Ltd., Vietnam, 2011-12 Education PhD. Atmospheric science, University of Birmingham, UK, 2016 MSc. Environmental science, University of Ulsan, South Korea, 2011 BSc. Chemistry (honours), Vietnam National University- Hanoi, Vietnam, 2008 Awards & fellowships Marie Curie early researcher fellowship, UK, 2013-16 Best paper presentation award, Brain Korea Program 21, 2010 Best paper award, International Forum on Strategic Technology, Korea, 2010 Outstanding student certificate, Hanoi University of Science, VNU, 2004-08 1st place (perfect score) in entrance exams, Vietnam National University, 2004 Research & teaching Research: Human exposure modelling, physical & chemical properties, sources and health effects of aerosols; numerical analysis & applied statistics/machine learning for air quality modelling Teaching: “MSc Air Pollution & Control” in Fall at University of Birmingham, 2018-2020 “MSc global pollution” at King’s College London, UK, 2019. Main research projects 1. NERC, “An Air Pollution Exposure model to integrate protection of vulnerable groups into the UK Clean Air Programme” (role: researcher): £1.4m, 2019-22 2. NERC grant “Quantitative attribution of secondary organic aerosol in Beijing to its precursors” (role: principal proposal writer & researcher): £273k, 2019-21 3. NERC “Sources and emissions of air pollutants in Beijing” (researcher): £1.4m, 2016-2020 4. -

Problem Solving Matters 2017

Problem Solving Matters 2017 Developing the problem solving skills necessary for the Mathematics Admission Test and the Test of Mathematics for University Admission This course is for year 12 students from state-funded schools, academies and colleges who are interested in applying for places at Oxford University, Imperial College, Durham University and Warwick University to study Mathematics. Students applying for places to study Mathematics or Computer Science courses (including joint honours) at Oxford University and any Mathematics undergraduate course at Imperial College, London will be required to sit the Mathematics Admission Test (MAT) as one part of the admissions process. Students applying for Mathematics at Durham University or Warwick University may be required to sit the MAT or TMUA (Test of Mathematics for University Admission) examination. This course is designed to prepare students for the way they will have to think to achieve success in the MAT, TMUA and other problem-solving mathematics examinations by developing their mathematical thinking and problem solving skills. The course consists of three face to face study days (at one of the University of Oxford, Imperial College London, Durham University and Warwick University), three summer assignments, and five online follow-up sessions. The course consists of Three face to face study days At Oxford University these will take place on Saturday 24th June 2017, Saturday 8th July 2017 and Saturday 8th October 2017 At Imperial College, London these will take place on Saturday 24th June 2017, Saturday 8th July 2017 and Saturday 23rd September 2017. At Warwick University Saturday 17th June 2017, Saturday 8th July 2017 and Saturday 16th September 2017 At Durham University Dates to be confirmed. -

Research Culture and Environment Toolkit

Research Culture and Environment Toolkit Russell Group Research Culture and Environment Toolkit I Acknowledgements This report was authored by Grace Gottlieb, Stephanie Smith, Jess Cole and Adam Clarke. We would like to thank Professor Colette Fagan (University of Manchester) for her contributions to the report and all Russell Group members for their engagement with the project and for their case studies. We are very grateful to the many individuals from across the sector who took the time to have such thoughtful, engaging and constructive conversations with us to inform this work. II Russell Group Research Culture and Environment Toolkit Introduction The Russell Group wants to promote the best environment for UK research and researchers to thrive. Through conversations and interviews with nearly 100 representatives from across the UK academic research ecosystem, we have looked at the current state of play, identifying what is good about our research environment and culture, as well as the challenges which need to be addressed. We have brought together these ideas and examples of good practice into a report, ‘Realising Our Potential: Backing Talent and Strengthening UK Research Culture and Environment’ demonstrating some of the work Russell Group universities are doing to support a vibrant, diverse and productive research culture. This accompanying toolkit collates all of the practical ideas and suggestions we have gathered through our research and stakeholder engagement into one place under the following themes: 1. Research careers Career stability Career progression Recognition and reward 2. The experience of working in research Wellbeing, management and support Visibility, sense of community and engagement 3. -

Veterinary Students As Global Citizens

Veterinary Students as Global Citizens Exploring opportunities for embedding the global dimension in the undergraduate veterinary curriculum Funded by This report has been funded by UK aid from the UK Government, however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies. The views expressed in this report are the opinions of the authors based on the experience gained during the Students as Global Citizens project and do not necessarily reflect the views of their institutions or wider professions. 1 Veterinary Students as Global Citizens Exploring opportunities for embedding the global dimension in the undergraduate veterinary curriculum Authors Jenny Maud Project Officer, Students as Global Citizens Royal Veterinary College Nicole Blum Lecturer in Development Education Development Education Research Centre Institute of Education Nick Short Head, E-Media Unit Royal Veterinary College Nigel Goode Senior Lecturer in Comparative Biomedical Sciences Royal Veterinary College © Royal Veterinary College, University of London and Development Education Research Centre, Institute of Education, 2012. Published by Royal Veterinary College and Development Education Research Centre, Institute of Education. ISBN: 978-0-9574546-4-4 2 Contents Foreword 3 Executive Summary 4 Introduction 5 What is the global dimension of veterinary medicine? 8 Why is it important to include the global dimension in veterinary education? 12 How can the global dimension be included in the veterinary curriculum? 16 What are the key challenges? 24 Conclusions 28 Further resources on global veterinary medicine and global awareness 29 References 30 3 Foreword Veterinary surgeons are extremely well placed to positively influence the future health and welfare of all animals, including humans.