Reaction to Indian Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Search of Beef Producton Nirvana

Chip Ramsay, Rex Ranch June 16, 2016 Nirvana: What does that mean? In Search of Beef Produc0on Nirvana • In the Buddhist tradi5on, nirvana is described as the ex5nguishing of the fires that cause suffering and rebirth.[29] These fires are typically iden5fied as the fires of aachment (raga), aversion (dvesha) and ignorance (moha or avidya). • In Hindu philosophy, it is the union with Brahman, the divine ground of existence, and the experience of blissful Things a cow-calf producer learns when you egolessness.[8] own a feedyard: what drives profit? Challenges we face: Rex Ranch • Weather volality •Price volality • Trust between segments • Adding real value to our produc5on • Answers come excruciangly slow (Environment or Genec?) • 2 year concep5on to harvest Excel Beef •7 year gene5c interval Deseret Cattle • Applying research findings correctly in various systems Feeders Weather Volality Table 3. Rex Ranch Annual Calf Cost ($/head) The following events are based on a 201 Average true story. 1 2012 2013 2014 2015 Variao Calf Cost 453 635 876 591 579 n Variaon from previous year (20) 182 241 (285) (12) 148 BIF 2016 General Session II 1 Chip Ramsay, Rex Ranch June 16, 2016 Trust between Price Volality segments • Weighing condi5ons • Do what is best for the cale instead of worry • Streamline vaccinaon about who gets the Table 2. Percentage variaon in revenue per head from one year protocol advantage. to the next • Sharing in added value ??? 201 201 201 201 5 year Avg. $/ 2 3 4 5 2016 avg.d head e Jan-Mar 550 lb. Steer a 16% -2% 26% 28% -30% 20% $ -

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal's Discourses)

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal’s Discourses) Acknowledgement of Source Material: Ra. Ganapthy’s ‘Deivathin Kural’ (Vol.6) in Tamil published by Vanathi Publishers, 4th edn. 1998 URL of Tamil Original: http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-74.htm to http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-141.htm English rendering : V. Krishnamurthy 2006 CONTENTS 1. Essence of the philosophical schools......................................................................... 1 2. Advaita is different from all these. ............................................................................. 2 3. Appears to be easy – but really, difficult .................................................................... 3 4. Moksha is by Grace of God ....................................................................................... 5 5. Takes time but effort has to be started........................................................................ 7 8. ShraddhA (Faith) Necessary..................................................................................... 12 9. Eligibility for Aatma-SAdhanA................................................................................ 14 10. Apex of Saadhanaa is only for the sannyAsi !........................................................ 17 11. Why then tell others,what is suitable only for Sannyaasis?.................................... 21 12. Two different paths for two different aspirants ...................................................... 21 13. Reason for telling every one .................................................................................. -

Indian Psychology: the Connection Between Mind, Body, and the Universe

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2010 Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe Sandeep Atwal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Atwal, Sandeep, "Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe" (2010). Theses and Dissertations. 64. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/64 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology INDIAN PSYCHOLOGY: THE CONNECTION BETWEEN MIND, BODY, AND THE UNIVERSE A clinical dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Psychology by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. July, 2010 Daryl Rowe, Ph.D. – Dissertation Chairperson This clinical dissertation, written by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY ______________________________________ Daryl Rowe, Ph.D., Chairperson ______________________________________ Joy Asamen, Ph.D. ______________________________________ Sonia Singh, -

Journal Für Religionskultur

________________________________ Journal of Religious Culture Journal für Religionskultur Ed. by / Hrsg. von Edmund Weber in Association with / in Zusammenarbeit mit Matthias Benad, Mustafa Cimsit, Natalia Diefenbach, Alexandra Landmann, Martin Mittwede, Vladislav Serikov, Ajit S. Sikand , Ida Bagus Putu Suamba & Roger Töpelmann Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main in Cooperation with the Institute for Religious Peace Research / in Kooperation mit dem Institut für Wissenschaftliche Irenik ISSN 1434-5935 - © E.Weber – E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] http://web.uni-frankfurt.de/irenik/religionskultur.htm; http://irenik.org/publikationen/jrc; http://publikationen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/solrsearch/index/search/searchtype/series/id/16137; http://web.uni-frankfurt.de/irenik/ew.htm; http://irenik.org/ ________________________________ No. 215 (2016) Dang Hyang Astapaka and His Cultural Geography in Spreading Vajrayana Buddhism in Medieval Bali1 By Ida Bagus Putu Suamba2 Abstract The sway of Hinduism and Buddhism in Indonesia archipelago had imprinted deep cultural heritages in various modes. The role of holy persons and kings were obvious in the spread of these religious and philosophical traditions. Dang Hyang Asatapaka, a Buddhist priest from East Java had travelled to Bali in spreading Vajrayana sect of Mahayana Buddhist in 1430. He came to Bali as the ruler of Bali invited him to officiate Homa Yajna together with his uncle 1 The abstract of it is included in the Abstact of Papers presented in the 7th International Buddhist Research Seminar, organized by the Buddhist Research Institute of Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Ayutthaya, Thailand held from the 18th to the 20th of January, 2016 (2559 BE) at Mahachulalongkornrajavidy- alaya University, Nan Sangha College, Nan province. -

ADVAITA 18 Diagrams Combined

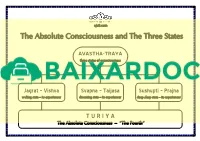

ajati.com The Absolute Consciousness and The Three States AVASTHA-TRAYA three states of consciousness Jagrat – Vishva Svapna – Taijasa Sushupti – Prajna waking state – its experiencer dreaming state – its experiencer deep sleep state – its experiencer TURIYA The Absolute Consciousness – “The Fourth“ ajati.com Bodies, Sheaths, States and Internal Instrument Sharira-Traya Pancha-Kosha Avastha-Traya Antahkarana Three Bodies Five Sheaths Three States Internal Instrument Sthula Sharira Annamaya Kosha Jagrat - Waking Ahamkara - Ego - Active (1) (1) (1) Buddhi - Intellect - Active Gross Body Food Sheath Vishva - Experiencer Manas - Mind - Active Chitta - Memory - Active Pranamaya Kosha (2) Vital Sheath Ahamkara - Ego - Inactive Sukshma Sharira Manomaya Kosha Svapna - Dream Buddhi - Intellect - Inactive (2) (3) (2) Subtle Body Mental Sheath Taijasa - Experiencer Manas - Mind - Inactive Chitta - Memory - Active Vijnanamaya Kosha (4) Intellect Sheath Ahamkara - Ego - Inactive Karana Sharira Anandamaya Kosha Sushupti - Deep Sleep Buddhi - Intellect - Inactive (3) (5) (3) Manas - Mind - Inactive Causal Body Bliss Sheath Prajna - Experiencer Chitta - Memory - Inactive ajati.com Description of Ignorance Ajnana – Characteristics Anadi Anirvachaniya Trigunatmaka Bhavarupa Jnanavirodhi Indefinable either as Made of three Experienced, Removed by Beginningless real (sat) or unreal (asat) tendencies (guna-s) hence present knowledge (jnana) Sattva Rajas Tamas Ajnana – Powers Avarana - Shakti Vikshepa - Shakti Veiling Power Projecting Power veils jiva 's real -

Chapter-N Cetasika (Mental Factors) 2.0. Introduction

44 Chapter-n Cetasika (Mental Factors) 2.0. Introduction In the first chapter, Citta (Consciousness) has been introduced. In this chapter, Cetasika (Mental factors) which means depending on citta will be discussed in detail with reference to the Abhidhamma pitaka by dividing topics and subtopics related to the present chapter. In the eighty-nine types of consciousness, enumerated in the first chapter, fifty-two mental factors arise in varying degree.There are seven concomitants common to every consciousness. There are six others that may or may not arise in each and every consciousness. They are termed Pakinnakas or Ethically variable factors. All these thirteen are designated Annasamanas, a rather peculiar technical term. Anna means other, samana means common. Sobhanas (Good), when compared with Asobhanas (Evil), are called Aiina (other) 'being of the opposite category'. Thus the Asobhanas are in contradistinction to Sobhanas. These thirteen become moral or immoral according to the types of consciousness in which they occur. 45 The fourteen concomitants are invariably found in every type of immoral consciousness. The nineteen are common to all type of moral consciousness. The six are moral concomitants which occur as occasion arises. Therefore these fifty-two (7+6+14+19+6=52) are found in all the types of consciousness in different proportions. In this chapter all the 52- mental factors are enumerated and classified. Every type of consciousness is microscopically analysed, and the accompanying psychic factors are given in details. The types of consciousness in which each mental factor occurs, is also described. 2.1. Definition of Cetasika Cetasika=cetas+ika When citta arises, it arises with mental factors that depend on it. -

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Dhyana Vahini 5 Publisher’s Note 6 PREFACE 7 Chapter I. The Power of Meditation 10 Binding actions and liberating actions 10 Taming the mind and the intelligence 11 One-pointedness and concentration 11 The value of chanting the divine name and meditation 12 The method of meditation 12 Chapter II. Chanting God’s Name and Meditation 14 Gauge meditation by its inner impact 14 The three paths of meditation 15 The need for bodily and mental training 15 Everyone has the right to spiritual success 16 Chapter III. The Goal of Meditation 18 Control the temper of the mind 18 Concentration and one-pointedness are the keys 18 Yearn for the right thing! 18 Reaching the goal through meditation 19 Gain inward vision 20 Chapter IV. Promote the Welfare of All Beings 21 Eschew the tenfold “sins” 21 Be unaffected by illusion 21 First, good qualities; later, the absence of qualities 21 The placid, calm, unruffled character wins out 22 Meditation is the basis of spiritual experience 23 Chapter V. Cultivate the Blissful Atmic Experience 24 The primary qualifications 24 Lead a dharmic life 24 The eight gates 25 Wish versus will 25 Take it step by step 25 No past or future 26 Clean and feed the mind 26 Chapter VI. Meditation Reveals the Eternal and the Non-Eternal 27 The Lord’s grace is needed to cross the sea 27 Why worry over short-lived attachments? 27 We are actors in the Lord’s play 29 Chapter VII. -

The Edicts of King Ashoka

THE EDICTS OF KING ASHOKA An English rendering by Ven. S. Dhammika THE EDICTS OF KING ASHOKA Table of Contents THE EDICTS OF KING ASHOKA........................................................................................................................1 An English rendering by Ven. S. Dhammika.................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................2 THE FOURTEEN ROCK EDICTS...............................................................................................................4 KALINGA ROCK EDICTS..........................................................................................................................8 MINOR ROCK EDICTS...............................................................................................................................9 THE SEVEN PILLAR EDICTS..................................................................................................................10 THE MINOR PILLAR EDICTS..................................................................................................................13 NOTES.........................................................................................................................................................13 -

Cūḷa Sīha,Nāda Sutta

M 1.1.1 Majjhima Nikya 1, Mūla Paṇṇāsa 1, Sīha,nāda Vagga 1 2 Cūḷa Sīha,nāda Sutta The Lesser Discourse on the Lion-roar | M 11 Theme: Witnessing the true teaching and Buddhist missiology Translated & annotated by Piya Tan ©2015 0 The Cūḷa Sīha,nāda Sutta: summary and highlights 0.1 THE LION-ROAR 0.1.1 What is a lion-roar? 0.1.1.1 The Cūḷa Sīha,nāda Sutta opens with the Buddha encouraging us to make a lion-roar, a public witness of faith that the true liberated saints (the arhats) are found only in the Buddha’s teaching [5.1.1]. The imagery of the lion-roar is based on the well known nature of the lion, as described here, in the (Anicca) Sīha Sutta (A 2.10): 3 “The lion, bhikshus, king of the beasts, in the evening emerges from his lair. Having emerg- ed, he stretches himself, surveys the four quarters all around, roars his lion-roar thrice, and then leaves for his hunting-ground. [85] 4 Bhikshus, when the animals and creatures hear the roar of the lion, the king of the beasts, they, for the most part, are struck with fear, urgency1 and trembling.2 Those that live in holes, enter their holes; the water-dwellers head into the waters; the forest- dwellers, seek the forests; winged birds resort to the skies.3 5 Bhikshus, those royal elephants bound by stout bonds, in the villages, market towns and capitals—they break and burst their bonds, and flee about in terror, voiding and peeing. -

Nibbedhika (Pariyāya) Sutta

A 6.2.1.9 Aṅguttara Nikāya 6, Chakka Nipāta 2, Dutiya Paṇṇāsaka 1, Mahā Vagga 9 11 Nibbedhika (Pariyāya) Sutta The Discourse on (the Exposition on) Penetrating Insight | A 6.63 Theme: A novel application of the noble truths as an overview of the way to spiritual freedom Translated with notes by Piya Tan ©2003, 2011 1 Sutta highlights 1.1 This popular sutta is often quoted in the Commentaries.1 It is a summary of the whole Teaching as the Way in six parallel methods, each with six steps: sensual desire, feelings, perceptions, mental influxes, karma, and suffering —each to be understood by its definition, diversity (of manifestation), result, cessa- tion and the way to its cessation. It is a sort of extended “noble truth” formula [§13]. In fact, each of analytical schemes of the six defilements (sensual desire, etc) is built on the structure of the 4 noble truths with the additional factors of “diversity” and of “result.” The Aṅguttara Comment- ary glosses “diversity” as “various causes” (vemattatā ti nānā,kāraṇaṁ, AA 3:406). In other words, it serves as an elaboration of the 2nd noble truth, the various internal or subjective causes of dukkha. “Re- sult” (vipāka), on the other hand, shows the external or objective causes of dukkha. 1.2 The Aṅguttara Commentary takes pariyāya here to mean “cause” (kāraṇa), that is, a means of pene- trating (that is, destroying) the defilements: “It is called ‘penetrative’ (nibbedhika) because it penetrates the mass of greed, etc, which had never before been penetrated or cleaved.” (AA 3:223) The highlight of the exposition is found in these two remarkable lines of the sutta’s only verse: The thought of lust is a person’s desire: The diversely beautiful in the world remain just as they are. -

Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition

REVISED EDITION John Powers ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 1 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 2 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 3 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism revised edition by John Powers Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york • boulder, colorado ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 4 Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 • Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 • www.snowlionpub.com © 1995, 2007 by John Powers All rights reserved. First edition 1995 Second edition 2007 No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. Designed and typeset by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Powers, John, 1957- Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism / by John Powers. — Rev. ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-55939-282-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-55939-282-7 (alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—China—Tibet. 2. Tibet (China)—Religion. I. Title. BQ7604.P69 2007 294.3’923—dc22 2007019309 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 5 Table of Contents Preface 11 Technical Note 17 Introduction 21 Part One: The Indian Background 1. Buddhism in India 31 The Buddha 31 The Buddha’s Life and Lives 34 Epilogue 56 2. Some Important Buddhist Doctrines 63 Cyclic Existence 63 Appearance and Reality 71 3. Meditation 81 The Role of Meditation in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism 81 Stabilizing and Analytical Meditation 85 The Five Buddhist Paths 91 4. -

A Translation of the Sokushin-Jobutsu-Gi

A Translation of the 密 Sokushin-Jobutsu-gi 教 文 Stephan Beyer 化 [I. INTRODUCTION: TEXTUAL SOURCES] Question: Many sutras and sastras say that it takes three kalpas to become a Buddha; on what grounds do you base the principle you have now set up that one may become a Buddha in this very body? Answer: The Tathagata has spoken in this way in the esoteric collection. Question: What are the sutras which say this? Answer: The Vajrasekhara-sutra says: One who cultivates this samadhi immediately realizes the enlightenment of the Buddha. ('This samadhi' means the samadhi of Mahavairocana, the noble monarch crowned by the single letter [bhrum].) And it says further: If there is a being who receives this teaching and diligently cultivates it during the four watches of the day and of the night, then in the present world he will realize and attain the pramudita-bhumi and, after sixteen lives, complete enlight- enment. (When this says 'teaching', it indicates the king of great teachings, the samadhi wherein one realizes the dharmakaya within oneself. ' Pramudita-bhumi' is not what. the exoteric schools explain as the first bhumi, but is rather the first bhumi in the Buddha-yana of our own school, as is fully explained in the Bhumi-varga. 'Sixteen lives' indicates the lives of the sixteen bodhisattvas, as the Bhumi-varga also fully explains.) And it says further: If one is able to cultivate in accordance with this sovereign principle, then in this present world one attains the highest perfect enlightenment. -96- It also says: You should know that your