The Effect of a Pardon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compensation Chart by State

Updated 5/21/18 NQ COMPENSATION STATUTES: A NATIONAL OVERVIEW STATE STATUTE WHEN ELIGIBILITY STANDARD WHO TIME LIMITS MAXIMUM AWARDS OTHER FUTURE CONTRIBUTORY PASSED OF PROOF DECIDES FOR FILING AWARDS CIVIL PROVISIONS LITIGATION AL Ala.Code 1975 § 29-2- 2001 Conviction vacated Not specified State Division of 2 years after Minimum of $50,000 for Not specified Not specified A new felony 150, et seq. or reversed and the Risk Management exoneration or each year of incarceration, conviction will end a charges dismissed and the dismissal Committee on claimant’s right to on grounds Committee on Compensation for compensation consistent with Compensation Wrongful Incarceration can innocence for Wrongful recommend discretionary Incarceration amount in addition to base, but legislature must appropriate any funds CA Cal Penal Code §§ Amended 2000; Pardon for Not specified California Victim 2 years after $140 per day of The Department Not specified Requires the board to 4900 to 4906; § 2006; 2009; innocence or being Compensation judgment of incarceration of Corrections deny a claim if the 2013; 2015; “innocent”; and Government acquittal or and Rehabilitation board finds by a 2017 declaration of Claims Board discharge given, shall assist a preponderance of the factual innocence makes a or after pardon person who is evidence that a claimant recommendation granted, after exonerated as to a pled guilty with the to the legislature release from conviction for specific intent to imprisonment, which he or she is protect another from from release serving a state prosecution for the from custody prison sentence at underlying conviction the time of for which the claimant exoneration with is seeking transitional compensation. -

Life Imprisonment and Conditions of Serving the Sentence in the South Caucasus Countries

Life Imprisonment and Conditions of Serving the Sentence in the South Caucasus Countries Project “Global Action to Abolish the Death Penalty” DDH/2006/119763 2009 2 The list of content The list of content ..........................................................................................................3 Foreword ........................................................................................................................5 The summary of the project ..........................................................................................7 A R M E N I A .............................................................................................................. 13 General Information ................................................................................................... 14 Methodology............................................................................................................... 14 The conditions of imprisonment for life sentenced prisoners .................................... 16 Local legislation and international standards ............................................................. 26 Conclusion ................................................................................................................... 33 Recommendations ...................................................................................................... 36 A Z E R B A I J A N ........................................................................................................ 39 General Information .................................................................................................. -

Consolidation of Pardon and Parole: a Wrong Approach Henry Weihofen

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 30 Article 8 Issue 4 November-December Winter 1939 Consolidation of Pardon and Parole: A Wrong Approach Henry Weihofen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Henry Weihofen, Consolidation of Pardon and Parole: A Wrong Approach, 30 Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 534 (1939-1940) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. CONSOLIDATION OF PARDON AND PAROLE: A WRONG APPROACH HENRY WEMOFEN* There is a growing tendency throughout the United States to consolidate pardon with parole administration, and even with pro- bation. This movement seems to have met with almost unanimous approval; at least it has no opposition. It is the purpose of this paper to remedy that lack and furnish the spice of opposition. The argument for such consolidation-is that pardon and parole perform very largely the same function. A conditional pardon, particularly, is practically indistinguishable from a parole. But the governor, granting a conditional pardon, usually has no officers available to see that the conditions are complied with. Why not-, it is argued-assign this duty to parole officers? Moreover, it is felt to be illogical to have two forms of release so similar as parole and conditional pardon issuing from two different sources, one from the parole board and the other from the governor's office. -

Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders

Introductory Handbook on The Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES Cover photo: © Rafael Olivares, Dirección General de Centros Penales de El Salvador. UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2018 © United Nations, December 2018. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Preface The first version of the Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders, published in 2012, was prepared for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) by Vivienne Chin, Associate of the International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy, Canada, and Yvon Dandurand, crimi- nologist at the University of the Fraser Valley, Canada. The initial draft of the first version of the Handbook was reviewed and discussed during an expert group meeting held in Vienna on 16 and 17 November 2011.Valuable suggestions and contributions were made by the following experts at that meeting: Charles Robert Allen, Ibrahim Hasan Almarooqi, Sultan Mohamed Alniyadi, Tomris Atabay, Karin Bruckmüller, Elias Carranza, Elinor Wanyama Chemonges, Kimmett Edgar, Aida Escobar, Angela Evans, José Filho, Isabel Hight, Andrea King-Wessels, Rita Susana Maxera, Marina Menezes, Hugo Morales, Omar Nashabe, Michael Platzer, Roberto Santana, Guy Schmit, Victoria Sergeyeva, Zhang Xiaohua and Zhao Linna. -

May 2013 Prison Break

Prison Break Correctional Liability Update May 2013 Housing Gang Members Together: Can a Blood and a Crip Just Get Along? By Susan E. Coleman Inmates who are assaulted by other inmates, whether cell mates, co- workers, or inmates on the yard, often sue prison administrators for failing to protect them. After all, the Eighth Amendment has been interpreted by the courts to include a duty to protect prisoners. However, a vague risk of harm simply because prisons are violent places which house dangerous criminals is not enough to create liability; something more specific is required. In the case of Labatad v. Corrections Corporation of America, et al, decided on May 1, 2013, the Ninth Circuit found that even housing rival gang members together was insufficient under the circumstances to find that defendants were deliberately indifferent. Labatad, a State of Hawaii inmate incarcerated at the Saguaro Correctional Center, operated by the Corrections Corporation of America Susan E. (“CCA”), was assaulted by his cellmate in July 2009. Naturally, Labatad Coleman is sued CCA for failing to protect him, alleging deliberate indifference to a partner at his safety under the Eighth Amendment. Because Labatad’s assailant the law firm was a member of a rival prison gang, this suit might at first blush seem of Burke, to have some merit, in that prison officials should be aware of Williams & longstanding prison gang rivalries. For example, in California it would Sorensen, be highly unusual to house a Black Guerrilla Family associate with a where she Mexican Mafia affiliate, and some would argue that a violent specializes confrontation would be foreseeable. -

Indeterminate Sentence Release on Parole and Pardon Edward Lindsey

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 8 | Issue 4 Article 3 1918 Indeterminate Sentence Release on Parole and Pardon Edward Lindsey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Edward Lindsey, Indeterminate Sentence Release on Parole and Pardon, 8 J. Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 491 (May 1917 to March 1918) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. INDETERIMlNATE SENTENCE, RELEASE ON PAROLE AN) PARDON (REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE OF THE INSTITUTE.') EDWARD LINDSEY, 2 Chairman. The only new state to adopt the indeterminate sentence the past year is North Carolina. In that state, by act of March 7, 1917, entitled, "An act to regulate the treatment, handling and work of prisoners," it is provided that all persons convicted of crime in any of the courts of the state whose sentence shall be for five years or more shall be -sent to the State Prison and the Board of Directors of the State Prison "is herewith authorized and directed to establish such rules and regulations as may be necessary for developing a system for paroling prisoners." The provisions for indeterminate .sentences are as follows: "The various judges of the Superior Court -

Rules of Executive Clemency

RULES OF EXECUTIVE CLEMENCY TABLE OF CONTENTS RULES: 1. STATEMENT OF POLICY 2. ADMINISTRATION 3. PAROLE AND PROBATION 4. CLEMENCY I. Types of Clemency A. Full Pardon B. Pardon Without Firearm Authority C. Pardon for Misdemeanor D. Commutation of Sentence E. Remission of Fines and Forfeitures F. Specific Authority to Own, Possess, or Use Firearms G. Restoration of Civil Rights in Florida II. Conditional Clemency 5. ELIGIBILITY A. Pardons B. Commutations of Sentence C. Remission of Fines and Forfeitures D. Specific Authority to Own, Possess, or Use Firearms E. Restoration of Civil Rights under Florida Law 6. APPLICATIONS A. Application Forms B. Required Supporting Documents C. Optional Supporting Documents D. Applicant Responsibility E. Failure to Meet Requirements F. Notification 7. APPLICATIONS REFERRED TO THE FLORIDA COMMISSION ON OFFENDER REVIEW 8. COMMUTATION OF SENTENCE A. Request for Review B. Referral to the Florida Commission on Offender Review C. Notification D. § 944.30 Cases E. Domestic Violence Case Review 9. AUTOMATIC RESTORATION OF CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER FLORIDA LAW WITHOUT A HEARING FOR FELONS WHO HAVE COMPLETED ALL TERMS OF SENTENCE PURSUANT TO AMENDMENT 4 AS DEFINED IN § 98.0751(2)(a), Fla. Stat. (2020) A. Criteria for Eligibility B. Action by Clemency Board C. Out-of-State or Federal Convictions 10. RESTORATION OF CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER FLORIDA LAW WITH A HEARING FOR FELONS WHO HAVE NOT COMPLETED ALL TERMS OF SENTENCE PURSUANT TO AMENDMENT 4 AS DEFINED IN § 98.0751(2)(a), Fla. Stat. (2020) A. Criteria for Eligibility B. Out-of-State or Federal Convictions 11. HEARINGS BY THE CLEMENCY BOARD ON PENDING APPLICATIONS A. -

Commuting Life Without Parole Sentences: the Need for Reason and Justice Over Politics

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History SJD Dissertations Academics Spring 5-1-2015 Commuting Life Without Parole Sentences: The Need for Reason and Justice over Politics Jing Cao Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/sjd Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Cao, Jing, "Commuting Life Without Parole Sentences: The Need for Reason and Justice over Politics" (2015). SJD Dissertations. 1. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/sjd/1 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Academics at FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in SJD Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMUTING LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE SENTENCES: THE NEED FOR REASON AND JUSTICE OVER POLITICS By Jing Cao A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Fordham University School of Law in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Juridical Science March, 2015 Fordham University New York, New York COMMUTING LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE SENTENCES: THE NEED FOR REASON AND JUSTICE OVER POLITICS Abstract In the last thirty years, life without parole (LWOP) sentences have flourished in the United States. Of course the very reason for a LWOP sentencing scheme is to incarcerate the convicted defendant until death. But under the Pardon Clause of the Constitution, as well as under state laws granting the Governor the pardoning power, inmates serving LWOP sentences might be eligible for early release by commutations.1 On the one hand, the possibility of clemency could be regarded as an impermissible loophole that could be used on a case-by-case basis to undermine the certainty of a LWOP sentencing system. -

Unconvicting the Innocent* Richard C

UNCONVICTING THE INNOCENT* RICHARD C. DONNELLYt "INNOCENT MAN IS UNABLE TO CLEAR RECORD AFTER 71/2 YEARS IN PRISON." Under this headline, the New York Times recently reported the courthouse tragedy of Nathan Kaplan, 49-year-old salesman. ' Mr. Kaplan's brush with the law began on September 28, 1937, when the Federal Government indicted him under the name of Nathan Kaplan, alias "Kitty," for the sale of heroin to a government undercover agent. Although he vigorously proclaimed his innocence from the day of his arrest, he did not take the witness stand at his trial. He was represented by able counsel and other due process requirements were fully observed. His defense was that Max Kaplan, alias "Brownsville Kitty," then a fugutive, had committed the crime. Mistaken identity was thus the central issue. Th9 government's case rested chiefly upon the testimony of three witnesses: Laura Miller, a prostitute and drug addict turned govern- ment informer; Murphy, the government agent to whom the sales were made; and another government agent who had observed the transactions. The jury believed the government's witnesses and found Nathan Kaplan guilty. He was sentenced to twelve years' imprison- ment, fined $2500, of which $500 was remitted, and placed on five years' probation to follow the prison term. He appealed, lost' and began serving his sentence in 1939. He served six years in prison, was released on conditional parole for the remaining six years and then placed on probation until June, 1956. More than a year after Nathan Kaplan's conviction, Max Kaplan surrendered and pleaded guilty to the same narcotics violation.' He was sentenced to eighteen months which he served in the Milan, Michigan, penitentiary where Nathan was serving his time, but Nathan never had an opportunity to talk with Max. -

Application for Pardon After Probation, Parole Or Discharge

CFJ-515A Rev. 6/2021 MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS OFFICE OF THE PAROLE BOARD APPLICATION FOR PARDON AFTER PROBATION, PAROLE OR DISCHARGE I hereby petition the Governor, as provided by law, for a pardon for the following conviction(s) in the State of Michigan and submit the following information in support of this application: 1. Name: ___________________________________________ Telephone #: (_____)______- ________ Address: __________________________________________________________________________ Marital Status: ( ) Married ( ) Divorced ( ) Single ( ) Widowed Number of Dependents: ______ 2. * Date of Birth: ___________ Place of Birth: _________________ U.S. Citizen: ( ) Yes ( ) No SS#: _____-____-_____ Sex: ( )Male ( )Female Race: ________ Michigan Prison #: _________ (* Information under question # 2 above used for identification and statistical purposes only) 3. Pursuant to statute, if you have been convicted of not more than one offense you may file an application with the convicting Court for the entry of an order setting aside the conviction. A person is not rendered ineligible for filing an application if they have also been convicted of not more than 2 minor offenses in addition to the offense for which the person files an application. “Minor Offense” means a misdemeanor or ordinance violation for which the maximum permissible imprisonment does not exceed 90 days, for which the maximum permissible fine does not exceed $1,000.00, and that it is committed by a person who is not more than 21 years of age. Have you reviewed the statutory criteria in 1965 PA 213, MCL 780.621 - MCL 780.624, seeking expungement/setting aside of the conviction of that crime? ( ) Yes ( ) No (Statutes can be found on the Michigan Legislative website at www.michiganlegislature.org) 4. -

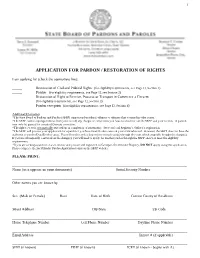

Application for Pardon / Restoration of Rights

1 APPLICATION FOR PARDON / RESTORATION OF RIGHTS I am applying for (check the appropriate line): _____ Restoration of Civil and Political Rights ( for eligibility requirements, see Page 11, Section 1) _____ Pardon ( for eligibility requirements, see Page 12, see Section 2) _____ Restoration of Right to Receive, Possess or Transport in Commerce a Firearm ( for eligibility requirements, see Page 12, Section 3) _____ Pardon exception ( for eligibility requirements, see Page 13, Section 4) Additional Information : *The State Board of Pardons and Paroles (SBPP) cannot pardon federal offenses or offenses that occurred in other states. *The SBPP cannot expunge (remove from your record) any charges or convictions you have received nor can the SBPP seal your records. A pardon may only be granted for a state of Georgia conviction. *The right to vote is automatically restored upon completion of sentence(s). See your local Registrar’s Office for registration. *The SBPP will process your application for a pardon if you have Dead Docket cases on your criminal record. However, the SBPP does not have the authority to pardon Dead Docket cases. You will need to seek a disposition on such case(s) through the court which originally brought the charge(s). If you are subsequently convicted on the charge(s), you will need to apply for another pardon through the SBPP once you meet the eligibility requirements. *If you are seeking a pardon for a sex offense and you are still registered on Georgia’s Sex Offender Registry, DO NOT apply using this application. Please complete the Sex Offender Pardon Application found on the SBPP website. -

Imagining a Path to Public Redemption

THE OPPOSITE OF PUNISHMENT: IMAGINING A PATH TO PUBLIC REDEMPTION Paul H. Robinson* and Muhammad Sarahne** ABSTRACT The criminal justice system traditionally performs its public functions—condemning prohibited conduct, shaming and stigmatizing violators, promoting societal norms—through the use of negative examples: convicting and punishing violators. One could imagine, however, that the same public functions could also be performed through the use of positive examples: publicly acknowledging and celebrating offenders who have chosen a path of atonement through confession, apology, making amends, acquiescing in just punishment, and promising future law abidingness. An offender who takes this path arguably deserves official public recognition, an update of all records and databases to record the public redemption, and an exemption from all collateral consequences of conviction. This article explores how and why such a system of public redemption might be constructed, the benefits it might provide to offenders, victims, and society, and the political complications that creation of such a system might encounter. * Colin S. Diver Professor of Law, University of Pennsylvania. The authors give special thanks for useful comments from Sarah Robinson, Adnan Zulfiqar, Ilya Rudyak, Stephen Garvey, Stephanos Bibas, and Kim Ferzan. © Paul H. Robinson ** S.J.D., 2020, University of Pennsylvania Law School, and Assistant to the Deputy Attorney General, Ministry of Justice, Israel. 1 2 RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 73:1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION