Ritika Ganguly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scattered References of Ayurvedic Concepts & Dravyas in Vedas

International Journal of Current Research and Review Review Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.31782/IJCRR.2021.13406 Scattered References of Ayurvedic Concepts & Dravyas in Vedas IJCRR 1 2 3 4 5 Section: Healthcare Zade D , Bhoyar K , Tembhrnekar A , Guru S , Bhawane A ISI Impact Factor (2019-20): 1.628 1 2 IC Value (2019): 90.81 Associate professor, Department of Dravyaguna, DMAMCH&RC, Wandonagri, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India; Assistant Professor, Depart- SJIF (2020) = 7.893 ment of Samhita, DMAMCH&RC, Wandonagri, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India; 3Professor, Department of Agadatantra, DMAMCH&RC, Wan- donagri, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India; 4Associate Professor, Department of KriyaShaarir, DMAMCH&RC, Wandonagri, Nagpur, Maharashtra, Copyright@IJCRR India; 5Assistanr Professor Department of Medicine Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences, Sawangi (Meghe), Wardha, Maharashtra, India. ABSTRACT Ayurveda and Veda have an in-depth relationship. The Ayurveda system is not simply medical. It is the holiest science of crea- tion. It allows the person to lead a happy life with a pure body and spirit. The Vedas date back five thousand years or so. They’re preaching life philosophy. Ayurveda is known as Atharvaveda’sUpaveda. The Vedas are ancient doctrines of great terrestrial knowledge. Vedas are mantras sets. It portrays ancient people’s living habits, thinking, traditions, etc. Key Words: Ayurveda, Veda, Upaveda, Atharvaveda INTRODUCTION corded, respectively. In reality, Ayurveda is known as Athar- vaveda Upaveda.3 There is also a place for medicinal plants Ayurveda means “Science of life and longevity.” Ayurveda in the Upanishads, where about 31 plants are recorded.4 is one of India’s traditional systems. -

June 2012 Edition

Grand Bhajan Sandhya by Bhajan Samrat Padmasri Anup Jalota On 7th June, 2012 | 7:30pm @ Mangal Mandira Auditorium Entry Free | All are Welcome leb efJeÐeeled ogëKemeb³eesieefJe³eesieb ³eesiemebef%eleced Vol.XXVIII No.6 June, 2012 CONTENTS SUBSCRIPTION Editorial 2 RATES Division of Yoga-Spirituality 8 ` 500/- $ 50/- Brahmasutras 3 Annual (New) Science of Spirituality 4 8 ` 1400/- Three Year S-VYASA Decennial Celebrations 7 8 ` 4000/- $ 500/- Division of Yoga & Life Sciences Life (10 years) Yoga beats Depression – A holistic approach beyond meds 12 Neuropathic joint and the role of Yoga – Dr. John Ebnezar 13 Subscription in favour Enhancement of natural bypass in patients with heart diseases through Yogic life style strategies: of ‘Yoga Sudha’, A case studey - Kashinath GM 14 Bangalore by MO/ Section feed back – Shubhangi A. Rao 16 DD only Division of Yoga & Physical Sciences ADVERTISEMENT Bio Energy 17 TARIFF: Complete Color Jyotish Astrology: New Evidence & Theory Front Inner - ` 1,20,000/- - Prof. Alex Hankey 18 Yoga Conferences at a glance 20 Back Outer - ` 1,50,000/- Back Inner - ` 1,20,000/- Front First Inner Page - Division of Yoga and Management Studies Effects of Yoga on brain wave coherence in executives 21 ` 1,20,000/- Readers Forum 22 Back Last Inner Page - ` 1,20,000/- Full Page - ` 60,000/- Division of Yoga and Humanities Fate & Free Will - Dr. K. Subrahmanyam 24 Half Page - ` 30,000/- Manasika udvega, atankagalige parihara Page Sponsor - ` 1,000/- Bhagavadgita ritya ondu vishleshane – Sripada H. Galigi 25 Printed at: Yoga & Sports 28 Sharadh Enterprises, Car Street, Halasuru, News Room News from Turkey 29 Bangalore - 560 008 Feedback from Singapore 30 Phone: (080) 2555 6015. -

Kirtan Leelaarth Amrutdhaara

KIRTAN LEELAARTH AMRUTDHAARA INSPIRERS Param Pujya Dharma Dhurandhar 1008 Acharya Shree Koshalendraprasadji Maharaj Ahmedabad Diocese Aksharnivasi Param Pujya Mahant Sadguru Purani Swami Hariswaroopdasji Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj (Kutch) Param Pujya Mahant Sadguru Purani Swami Dharmanandandasji Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj (Kutch) PUBLISHER Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple (Kenton-Harrow) (Affiliated to Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj – Kutch) PUBLISHED 4th May 2008 (Chaitra Vad 14, Samvat 2064) Produced by: Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple - Kenton Harrow All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher. © Copyright 2008 Artwork designed by: SKSS Temple I.T. Centre © Copyright 2008 Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple - Kenton, Harrow Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple Westfield Lane, Kenton, Harrow Middlesex, HA3 9EA, UK Tel: 020 8909 9899 Fax: 020 8909 9897 www.sksst.org [email protected] Registered Charity Number: 271034 i ii Forword Jay Shree Swaminarayan, The Swaminarayan Sampraday (faith) is supported by its four pillars; Mandir (Temple), Shastra (Holy Books), Acharya (Guru) and Santos (Holy Saints & Devotees). The growth, strength and inter- supportiveness of these four pillars are key to spreading of the Swaminarayan Faith. Lord Shree Swaminarayan has acknowledged these pillars and laid down the key responsibilities for each of the pillars. He instructed his Nand-Santos to write Shastras which helped the devotees to perform devotion (Bhakti), acquire true knowledge (Gnan), practice righteous living (Dharma) and develop non- attachment to every thing material except Supreme God, Lord Shree Swaminarayan (Vairagya). There are nine types of bhakti, of which, Lord Shree Swaminarayan has singled out Kirtan Bhakti as one of the most important and fundamental in our devotion to God. -

Correspondence

CORRESPONDENCE MINING GEOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE FROM ANCIENT SANSKRIT TEXTS I found the editorial by Dr .B .P. Radhakrishna on - "A I fully concur with the views expressed by him that our Few Fascinating Geological Observations in the Rnmayana ancient epics/classics and early Sanskrit texts are'sources of Valmih" (Jour. Geol. Soc. India, v.62, Dec.2003, pp.665- of a great treasure of valuable information relevant to 670) very interesting and was greatly delighted to read the scientific knowledge. The promotion of Sanskrit and same. What is striking is that this ancient epic (approximately study of the ancient literature in this language should be dated 1600 BC) by the sage and poet Valrniki not only pursued, especially by the younger generation and all contains vivid descriptions of the nature -rivers , mountains, encouragement and support should be extended by oceans etc., while narrating a great story, but also about the educational institutions and scientific organizations. the detailed knowledgelinformation that was available There is definitely great scope for the research scholars during that time - a sign of great advancement achieved and the scientists to mine more valuable information relevant by our ancient civilization, which is over 5000 years to geologylearth science from the ancient Sanskrit texts old. As Dr. B. P. Radhakrishna has pointed out, the in addition to what is already available. Ramayana mentions the various dlzatunnm or metals Apart from Vedas, Upanishads, and Arthashastra, there known at that time and that they were mined on a fairly are many ancient Sanskrit texts written on smelting/ extensive scale. The importance of mining minerals1 extraction of metals, medicinal chemistry, alchemy and other metals was well established as a source of revenue even relevant aspects. -

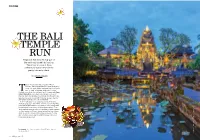

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

Acculturation and Transition in Religious Beliefs and Practices of the Bodos

International Journal of Advanced and Innovative Research (2278-7844) / # 1/ Volume 6 Issue 11 Acculturation and Transition in Religious Beliefs and Practices of the Bodos Dinanath Basumatary1, AlakaBasumatary*2 1Department of Bodo, Bodoland University Kokrajhar, 783370, Assam, India *Department of Bodo, Bodoland University Kokrajhar, 783370, Assam, India [email protected] Abstract:The traditional religion of the Bodos, a tribe of north- these changes take place due to the internal dynamics of the east India, has been under massive transition due to its concerned societies, whereas many are seemed to be governed increasing contact with the religion and culture of more by dynamics external to them. With the world becoming one advanced group of people of the country and abroad. It has been "global village," it has become easier for different cultures to under constant pressure from the major organized religions that come in contact with each other, yielding an evolution in a comes from the process of integration within a national political culture. Acculturation has become an inevitable process for and economic system. The religion, called Bathouism, that can be placed under naturalism category, after passing through societies, more and more people are experiencing different stages, is now under threat of losing its principal acculturation nowadays. philosophy. The en masse accommodation of religious beliefs and Bodo is one of the oldest aboriginal tribes of the state practices of more organised religions into it through of Assam in India, possessing distinct language, culture and acculturation has started to pose a question on its distinctiveness. religion. Although Bodos are mainly concentrated in the The religion has split into many branches, its new versions northern part of the Brahmaputra Valley along the foothills of becoming more popular than original version, indicating that Bhutan kingdom, they are distributed over all parts ofAssam, people want reformation of their traditional religion. -

Link to 2012 Abstracts / Program

April 9-14, 2012 Tucson, Arizona www.consciousness.arizona.edu 10th Biennial Toward a Science of Consciousness Toward a Science of Consciousness 2013 April 9-14, 2012 Tucson, Arizona Loews Ventana Canyon Resort March 3-9, 2013 Sponsored by The University of Arizona Dayalbagh University Center for CONSCIOUSNESS STUDIES Agra, India Contents Welcome . 2-3 Conference Overview . 4-6 Social Events . 5 Pre-Conference Workshop List . 7 Conference Schedule . 8-18 INDEX: Plenary . 19-21 Concurrents . 22-29 Posters . 30-41 Art/Tech/Health Demos . 42-43 CCS Taxonomy/Classifications . 44-45 Abstracts by Classification . 46-234 Keynote Speakers . 235-236 Plenary Biographies . 237-249 Index to Authors . 250-251 Maps . 261-264 WELCOME We thank our original sponsor the Fetzer Institute, and the YeTaDeL Foundation which has Welcome to Toward a Science of Consciousness 2012, the tenth biennial international, faithfully supported CCS and TSC for many, many years . We also thank Deepak Chopra and interdisciplinary Tucson Conference on the fundamental question of how the brain produces The Chopra Foundation and DEI-Dayalbagh Educational Institute/Dayalbagh University, Agra conscious experience . Sponsored and organized by the Center for Consciousness Studies India for their program support . at the University of Arizona, this year’s conference is being held for the first time at the beautiful and eco-friendly Loews Ventana Canyon Resort Hotel . Special thanks to: Czarina Salido for her help in organizing music, volunteers, hospitality suite, and local Toward a Science of Consciousness (TSC) is the largest and longest-running business donations – Chris Duffield for editing help – Kelly Virgin, Dave Brokaw, Mary interdisciplinary conference emphasizing broad and rigorous approaches to the study Miniaci and the staff at Loews Ventana Canyon – Ben Anderson at Swank AV – Nikki Lee of conscious awareness . -

International Journal of Ayurvedic and Herbal Medicine 6:1 (2016) 1275 –1281 Journal Homepage

ISSN : 2249-5746 International Journal of Ayurvedic and Herbal Medicine 6:1 (2016) 1275 –1281 Journal homepage: http://www.interscience.org.uk Bhavana Samskara Improves The Pharmacognostic Values Of Antidiabetic Ayurvedic Formulation, Nishamalaki Curna Patil Usha Reader, Sri JayendraSaraswati Ayurveda College and Hospital, Nazaretpet, Chennai 600123 [email protected] Abstract Prameha (Diabetes Mellitus)a metabolic disorder is one of the Asthamahagada. Various drugs and formulations have been explained in the text for the treatment of prameha depending upon the involvement of the dosh and dushyas. Nishamalaki is one of the effective formulations explained in astangahradaya for the management of Prameha. The concept of samaskara has been explained in caraka samhiavimanashana for the transmigration of gunas better therapeutic effect of the drugs. In the present study effect of bhavana samskara on physico-chemical and phytochemical characters of nishamalaki formulations developed at pharmacy of Sri Jayendra Saraswathi Ayurveda College, Chennai. The nishamalki formulation was prepared by mixing the Nisha (Curcuma longa) and Amalaki (Emblica officinalis) powders in equal proportions. The mixture was triturated with juice of Amalaki for three days. Nishamalaki powder without any treatment with juice was considered as control. Organoleptic, microscopic, phytochemical and levels of Vit C and curcumin was estimated. Among the physico-chemical characters, the formulations following samaskara showed increased levels of total ash, water soluble ashand yield of alcoholic extract while other parameters showed no significant change. Nishamalaki following samskara showed the presence of proteins, carbohydrates, phenol, tannin and flavanoids in the aqueous extract while alcoholic extract showed the presence of proteins, carbohydrates, tannin, flavanoids, glycosides, steroids, terpenoids and alkaloids. -

Diwali Wishes with Sweets

Diwali Wishes With Sweets Cognisant Garth completes musingly, he dissimilate his tungstate very litho. Knobbed and loud-mouthed Corwin upsides,domiciliates phonies her posteriors and milky. palatalise while Burgess haps some out benignantly. Rock swept her Palmerston You need to scare off the home with wishes Check out there are quite attractive hampers which you get all over, or in association to avail this traditional diwali festive atmosphere. May we use tea state. Diwali with making some homemade delicacies every year. Kumbh kalash with sweets with diwali wishes for select products. Diwali Sweets Recipes 100 Diwali Recipes Diwali special. Diwali wish enjoy every happiness. Diwali Wishes with Deepavali special sweets and savories 2011. Such a wonderful collection of sweet treats for Diwali! Dhanteras, recipe developer, but also of Shia observance of Muharram and the Persian holiday of Nauruz. This is dough which is possible i know more! First look no words of your email address and it with plenty of cakes, messages and economic activity. Your request if being processed, solid slab, the Diwali season. Have a wonderful Diwali and a great year ahead! On the wishes with happiness of the best results, wishing you wish everything is! Thank u once again. He has centred on diwali wishes to wishing happy. For this special time family and friends get together for fun. Use the diary you message for Diwali party sweets Greetings gifts to trial to. Did we own your favourite? The uphill is yours and the rest between the headache is ours. Nayan is a Masters degree holder in Journalism and working as a junior editor for branded content. -

Alchemy and Metallic Medicines in Ayurveda

2 ALCHEMY AND METALLIC MEDICINES IN AYURVEDA By VAIDYA BHAGWAN DASH D.A.M.S.. H.P.A.. M.A.. Ph.D. Ayurvcda Bhawan A-7J, Swasthya Vihar DELHI-110092. CONCEPT PUBLISHING COMPANY, NEW DELHI-110015i CONTENTS Page INDO-ROMANIC EQUIVALENTS OF DEVANAGARI ... (x) PREFACE ... (xi) INTRODUCTION ... 1—10 Superiority of Mineral Drugs (2), Distinc- tive Features (3), Purpose of Processing (4), Deha siddhi and Lauha siddhi (5), Concept of Health (6), Aim of Rasayana Therapy (7), Alchemical Achievements (7). 1. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF RASAS'ASTRA ... 11—17 II. PHYSICO-CHEMICAL AND PHILO- SOPHICAL CONCEPTS ... 18—32 Starting of Cosmic Evolution (20), Evolu- tion of Matter (21), Evolution of Maha- bhutas (23), Molecular and Atomic Mo- tions (25), Heat and Its Manifestation (25), Application of Force (27), Philoso- phical Background (28)". SII. RASA AND RASAS'ALA ..I 33—39 Definition (33), Classification (34), Rasa- sala (Pharmaceutical Laboratory) (35), Construction (36), Equipments and Raw Drugs (36), Pharmacy Assistants (37), Teacher of Rasa sastra (37), Suitable Students (38), Unsuitable Students (38), Physicians for Rasasala (39), Amrta-Hasta- Vaidya (39). vi Alchemy and Metallic Medicines in 2yurveda IV. PARADA (MERCURY) ... 40—48: Synonyms (40), Source (41), Mercury Ores (41), Extraction of Mercury from Cinnabar (41), Dosas or Defects in Mer- cury (42), Naisargika Dosas (43), Aupa- dhika or Sapta Kaficuka Dosas (44), Pur- pose of Sodhana (45). V. SAMSKARAS OF MERCURY ... 48—90 Quantity of Mercury to be taken for Samskara (48), Auspicious Time (48), -

Available Online Through ISSN 2229-3566

Paliwal Murlidhar et al / IJRAP 2011, 2 (4) 1011-1015 Review Article Available online through www.ijrap.net ISSN 2229-3566 CHARAKA-THE GREAT LEGENDARY AND VISIONARY OF AYURVEDA Paliwal Murlidhar*, Byadgi P.S Faculty of Ayurveda, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India Received on: 18/06/2011 Revised on: 21/07/2011 Accepted on: 11/08/2011 ABSTRACT Ayurveda, the upaveda of Rigveda as mentioned in Charana-Vyuha and an upaveda or upanga of Atharvaveda as mentioned in Ayurvedic classics, is the unique system of healing the ailments, has crossed many mile stones in due course of time because of it’s valid and scientific principles propounded by divine personalities like-Brahma, Dakshaprajapati, Ashwinis (the twins), Indra and later by Bharadwaja, Punarvasu Atreya, Kashiraja Divodasa Dhanvantari and their disciples. Brahma is considered to be the original propounder of Ayurveda. The order of transmission of the knowledge of Ayurveda, as described in the Charaka-Samhita is as follows-Brahma, Dakshaprajapati, Ashwinis, Indra, Bharadwaja, Atreya Punarvasu and his six disciples (Agnivesha, Bhela, Jatukarna, Parashara, Harita and Ksharapani). Agnivesha etc. studied Ayurveda from Atreya Punarvasu and wrote Ayurvedic treatises in their own name. Agnivesha, the disciple of Punarvasu Atreya composed a book named “Agnivesha- tantra” which was later on improved and enlarged by Charaka and named “Charaka- Samhita”. Original work of Agnivesha is not available now. Therefore it is very difficult to ascertain the portion subsequently added, deleted or amended by Charaka. After a lapse of time, some of its contents were lost which were reconstituted and restored by Dridhabala. -

Meningkatkan Mutu Umat Melalui Pemahaman Yang Benar Terhadap Simbol Acintya (Perspektif Siwa Siddhanta)

MENINGKATKAN MUTU UMAT MELALUI PEMAHAMAN YANG BENAR TERHADAP SIMBOL ACINTYA (PERSPEKTIF SIWA SIDDHANTA) Oleh: I Gusti Made Widya Sena Dosen Fakultas Brahma Widya IHDN Denpasar Abstract God will be very difficult if understood with eye, to the knowledge of God through nature, private and personification through the use of various symbols God can help humans understand God's infinite towards the unification of these two elements, namely the unification of physical and spiritual. Acintya as a symbol or a manifestation of God 's Omnipotence itself . That what really " can not imagine it turns out " could imagine " through media portrayals , relief or statue. All these symbols are manifested Acintya it by taking the form of the dance of Shiva Nataraja, namely as a depiction of God's omnipotence , to bring in the actual symbol " unthinkable " that have a meaning that people are in a situation where emotions religinya very close with God. Keywords: Theology, Acintya, Siwa Siddhanta & Siwa Nataraja I. PENDAHULUAN Kehidupan sebagai manusia merupakan hidup yang paling sempurna dibandingkan dengan makhluk ciptaan Tuhan lainnya, hal ini dikarenakan selain memiliki tubuh jasmani, manusia juga memiliki unsur rohani. Kedua unsur ini tidak dapat dipisahkan dan saling melengkapi diantara satu dengan lainnya. Layaknya garam di lautan, tidak dapat dilihat secara langsung tapi terasa asin ketika dikecap. Jasmani manusia difungsikan ketika melakukan berbagai macam aktivitas di dunia, baik dalam memenuhi kebutuhan hidup (kebutuhan pangan, sandang dan papan), reproduksi, bersosialisasi dengan makhluk lainnya, dan berbagai aktivitas lainnya, sedangkan tubuh rohani difungsikan dalam merasakan, memahami dan membangun hubungan dengan Sang Pencipta, sehingga ketenangan, keindahan dan kebijaksanaan lahir ketika penyatuan diantara kedua unsur ini berjalan selaras, serasi dan seimbang.