The Performers Alliance: Conflict and Change Within the Screen Actors Guild

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside Ripping Through the Catskills

March 2015 “Celebrating Age and Maturity” HABITS That WILL 18CHANGE Your LIFE Inside RIPPING THROUGH THE CATSKILLS HOW TO SURVIVE AN IRS AUDIT DECODING YOUR TAXES Live Here and It! You’re as young as you feel! Ponce de León never found his fountain of youth, but you can find yours at Tower at The Oaks. Our active adult lifestyle incorporates the seven dimensions of wellness to help you maintain your physical and emotional health and live life to the fullest no matter what your age. Dancing, croquet, cultural and educational programs, out-of-town trips. A world of things to do with a world of people to do them. And, you don’t have to travel half way around the world! Discover Tower at The Oaks, located within The Oaks of Louisiana community in southeast Shreveport. Live here and love it. 600 East Flournoy Lucas Road (318) 212-OAKS (6257) oaksofla.com Private tours available weekdays by appointment Drop-ins welcome 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. weekdays 2 March 2015 www.TheBestOfTimesNEWS.com DIRECT CREMATION $995 FOREST PARK WEST CEMETERY Cremation Memorial 4000 Meriwether Road Service from $2995 Shreveport, La. 71109 Funeral followed by 318-686-1461 cremation from $4995 FOREST PARK FUNERAL HOME “The Friendship Package” Wellman’s Memorial Chapel SINGLE GRAVE SPACE $1795 Funeral followed by “Unique Services Celebrating Unique Lives” burial from $5995 Includes Grave Liner, 1201 Louisiana Ave. Opening & Closing Shreveport, La. 71101 Other Funeral & Cremation Tent & Chairs for Graveside 318-221-7181 Packages Are Available. Services www.forestparkfh.com -

Eeann Tweeden, a Los Port for Franken and Hoped He an Injury to One Is an Injury to All! Angeles Radio Broadcaster

(ISSN 0023-6667) Al Franken to resign from U.S. Senate Minnesota U.S. Senator Al an effective Senator. “Minne- Franken, 66, will resign amidst sotans deserve a senator who multiple allegations of sexual can focus with all her energy harassment from perhaps eight on addressing the issues they or more women, some of them face every day,” he said. anonymous. Franken never admitted to The first charge came Nov. sexual harassing women. Many 16 from Republican supporter Minnesotans stated their sup- Leeann Tweeden, a Los port for Franken and hoped he An Injury to One is an Injury to All! Angeles radio broadcaster. She would not resign. Many posts WEDNESDAY VOL. 124 said Franken forcibly kissed stated that Franken was set up DECEMBER 13, 2017 NO. 12 and groped her during a USO to be taken down. Many former tour in 2006, two years before female staffers said he always he was elected to the U.S. treated them with respect. Senate. Photos were published Among other statements in Al Franken was in Wellstone of Franken pretending to grope his lengthy speech were “Over Hall in May 2005 addressing her breasts as she slept. the last few weeks, a number of an overflow crowd that Franken apologized and women have come forward to wanted him to run for U.S. called for a Senate ethics inves- talk about how they felt my Senate after he moved back tigation into his actions, but actions had affected them. I to Minnesota. He invoked disappeared until a Senate floor was shocked. I was upset. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

FIA-NA Resolutions

REGIONAL GROUP OF THE INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF ACTORS (FIA) A LLIANCE OF C ANADIAN C I N E M A , T ELEVISION AND R ADIO A RTISTS – C A N A D A A MERICAN E QUITY A SSOCIATION – USA A MERICAN F EDERATION OF T ELEVISION AND R ADIO A RTISTS – USA A SOCIACIÓN N ACIONAL DE A C T O R E S – M E X I C O C ANADIAN A C T O R S ’ E QUITY A SSOCIATION – C A N A D A S CREEN A C T O R S ’ G UILD – USA FIA-NA Resolution Blue Man Group Boycott Meeting in Toronto on May 14 and 15, 2005, the members of FIA-NA (FIA North America) including Actors’ Equity Association, Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, Canadian Actors' Equity Association, Screen Actors' Guild and Union des Artistes, pledged their continued support of Canadian Actors' Equity Association, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees - Locals 58 and 822 and the Toronto Musicians' Association - Local 149 of the American Federation of Musicians’ struggle to bring the Blue Man Group to the bargaining table. Blue Man Group will open a production in Toronto in June 2005 at the newly renovated Panasonic Theatre. Each FIA-NA affiliate will instruct its members to refuse to audition or provide service to this producer for the Toronto production until successful negotiations are concluded with the relevant Canadian associations and unions. We express disappointment at Panasonic Canada and Clear Channel Entertainment’s connection to this unfortunate situation and request that these organizations intervene directly to bring about resolution to this situation. -

Parleyp D Basics

"Ro"M t112" Wv 151 m. Vol. 24-oe 45 l2 - | -~~~~~~Noveenb*r 13,1i98t' 'ENIGINEERED RECES0 v 2 0 1981 -r~ff of c. Califoma's. unemployment rate Administration and that they are the Reagan economic, policy. It rose almost a full percentage point being offered nothing to help but julst won't work." -in October over September, from "more of the same." Representative Parren Mit hoiI 7.2% to 8.1%. This nearly doubled. Latweek when Secretary of (D-Md.),. a member of the con- the -nati-onal jobless rate increase Labor.Ray Doniov'an refused to gressional, joint econoihilc com- which went from .7.5% in Septem& -testify -before a Senate committee. mnittee, said the administration ber to 8.1% last. month, according -on -the unemployment prblem, has' underestimated the -prGblem. to U.S. -Labor Department figures, -Senator. -Edward Kenne-dy' (D- "My hunch,'" he said, "is tha't released'on November 6. Mass.) ch'aracter'ized. 'the- latest it's eventually going to gD high- AFL-CIO President Lane Kirk- national jobless figures as "the er than eight percent if' present land said American warkers have worst news for the economy is, policies are continued." been victimized by. "this. engi- the last -five years . We are House Speaker Thomas O'Neill neered recession" -of the Reagan' witnessing the 'disentegration of (Continued on Page 4) Pre'sident Reagan isattempting. eBomics, is the the" 'that gov- generations. ago. have all been' "tto repeal {lie 20th Century"' Jim ornment is inherelitly isnp'ro'duv government-' contributions which' Baker,. director of AFL1CIORe- ti-ve and an enemy of prodtudion. -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

Elegant Memo

Office of the Governor David Ronald Musgrove Governor Greetings! On behalf of the State of Mississippi, thank you for expressing an interest in our state, its history and the life of its citizens. I am proud to serve Mississippians as their governor. Mississippi is a beautiful state with a rich culture and a promising future. Our state is experiencing tremendous growth as evidenced by the lowest unemployment rate in thirty years, the significant increase in personal income levels, the astounding number of small businesses created in Mississippi, and national recognition of Mississippi’s potential for economic growth. Our schools are stronger. Our hope is broader, and our determination is unwavering. This is our Mississippi. Together, we have the courage, the confidence, the commitment to set unprecedented goals and to make unparalleled progress. Best wishes in all of your endeavors. May God bless you, the State of Mississippi and America! Very truly yours, RONNIE MUSGROVE State Symbols State Flag The committee to design a State Flag was appointed by legislative action February 7, 1894, and provided that the flag reported by the committee should become the official flag. The committee recommended for the flag “one with width two-thirds of its length; with the union square, in width two-thirds of the width of the flag; the State ground of the union to be red and a broad blue saltier Coat of Arms thereon, bordered with white and emblazoned with The committee to design a Coat of Arms was thirteen (13) mullets or five-pointed stars, corresponding appointed by legislative action on February 7, 1894, and with the number of the original States of the Union; the the design proposed by that committee was accepted and field to be divided into three bars of equal width, the became the official Coat of Arms. -

Retrospektive the Weimar Touch 1 a Midsummer Night's Dream Von Max

63. Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin Retrospektive The Weimar Touch A Midsummer Night’s Dream von Max Reinhardt und William Dieterle mit James Cagney, Dick Powell, Olivia De Havilland, Mickey Rooney. USA 1935. Englisch. Kopie: Bonner Kinemathek, Bonn Car of Dreams von Graham Cutts und Austin Melford mit Grete Mosheim, John Mills, Norah Howard, Robertson Hare. Großbritannien 1935. Englisch. Kopie: British Film Institute, National Film & Television Archive, London Casablanca von Michael Curtiz mit Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Conrad Veidt, Peter Lorre. USA 1942. Englisch. Restaurierte Fassung (2012). DCP: Warner Bros. Pictures UK, vertreten durch Park Circus, Glasgow Confessions of a Nazi Spy von Anatole Litvak mit Edward G. Robinson, Francis Lederer, George Sanders. USA 1939. Englisch. Kopie: Cinémathèque de la Ville de Luxembourg, Luxemburg Einmal eine große Dame sein von Gerhard Lamprecht mit Käthe von Nagy, Wolf Albach-Retty, Gretl Theimer, Werner Fuetterer. Deutschland 1934. Deutsch mit englischen elektronischen Untertiteln. Kopie: Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung, Wiesbaden Ergens in Nederland. Een film uit de Mobilisatietijd (Somewhere in the Netherlands) von Ludwig Berger mit Lilly Bouwmeester, Jan de Hartog, Matthieu van Eysden. Niederlande 1940. Niederländisch mit englischen elektronischen Untertiteln. Kopie: EYE Film Institute Netherlands, Amsterdam First a Girl von Victor Saville mit Jessie Matthews, Sonnie Hale, Anna Lee, Griffith Jones. Großbritannien 1935. Englisch. Kopie: British Film Institute, National Film & Television Archive, London Fury von Fritz Lang mit Sylvia Sidney, Spencer Tracy, Walter Abel. USA 1936. Englisch. Kopie: Deutsche Kinemathek – Museum für Film und Fernsehen, Berlin Gado Bravo von António Lopes Ribeiro und Max Nosseck mit Nita Brandão, Olly Gebauer, Siegfried Arno, Portugal 1934. Portugiesisch/Deutsch mit englischen elektronischen Untertiteln. -

Film Essay for "The Best Years of Our Lives"

The Best Years of Our Lives Homer By Gabriel Miller Wermels (Harold Russell), a “The Best Years of Our Lives” originated in a recommen- seaman, who dation from producer Samuel Goldwyn's wife that he read has long a “Time” magazine article entitled "The Way Home" been en- (1944), about Marines who were having difficulty readjust- gaged to the ing to life after returning home from the war. Goldwyn girl next door. hired novelist MacKinlay Kantor, who had flown missions He returns as a correspondent with the Eighth Air Force and the from the war Royal Air Force (and would go on to win the Pulitzer Prize a spastic, in 1955 for his Civil War novel “Andersonville”), to use that unable to article as the basis for a fictional adaptation of approxi- control his mately 100 pages. Inexplicably, Kantor turned in a novel movements. in verse that ran closer to 300 pages. Goldwyn could barely follow it, and he wanted to shelve the project but Sherwood was talked into letting Kantor work on a treatment. and Wyler made some William Wyler, his star director, returned to Goldwyn significant Studios in 1946, having been honorably discharged from changes that the Air Force as a colonel, also receiving the Legion of added more Merit Award. Wyler's feelings about his life and profession complexity had changed: "The war had been an escape into reality … and dramatic Only relationships with people who might be dead tomor- force to the row were important." Wyler still owed Goldwyn one more story. In film, and the producer wanted him to make “The Bishop's Kantor's ver- Wife” with David Niven. -

XXXI:4) Robert Montgomery, LADY in the LAKE (1947, 105 Min)

September 22, 2015 (XXXI:4) Robert Montgomery, LADY IN THE LAKE (1947, 105 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Directed by Robert Montgomery Written by Steve Fisher (screenplay) based on the novel by Raymond Chandler Produced by George Haight Music by David Snell and Maurice Goldman (uncredited) Cinematography by Paul Vogel Film Editing by Gene Ruggiero Art Direction by E. Preston Ames and Cedric Gibbons Special Effects by A. Arnold Gillespie Robert Montgomery ... Phillip Marlowe Audrey Totter ... Adrienne Fromsett Lloyd Nolan ... Lt. DeGarmot Tom Tully ... Capt. Kane Leon Ames ... Derace Kingsby Jayne Meadows ... Mildred Havelend Pink Horse, 1947 Lady in the Lake, 1945 They Were Expendable, Dick Simmons ... Chris Lavery 1941 Here Comes Mr. Jordan, 1939 Fast and Loose, 1938 Three Morris Ankrum ... Eugene Grayson Loves Has Nancy, 1937 Ever Since Eve, 1937 Night Must Fall, Lila Leeds ... Receptionist 1936 Petticoat Fever, 1935 Biography of a Bachelor Girl, 1934 William Roberts ... Artist Riptide, 1933 Night Flight, 1932 Faithless, 1931 The Man in Kathleen Lockhart ... Mrs. Grayson Possession, 1931 Shipmates, 1930 War Nurse, 1930 Our Blushing Ellay Mort ... Chrystal Kingsby Brides, 1930 The Big House, 1929 Their Own Desire, 1929 Three Eddie Acuff ... Ed, the Coroner (uncredited) Live Ghosts, 1929 The Single Standard. Robert Montgomery (director, actor) (b. May 21, 1904 in Steve Fisher (writer, screenplay) (b. August 29, 1912 in Marine Fishkill Landing, New York—d. September 27, 1981, age 77, in City, Michigan—d. March 27, age 67, in Canoga Park, California) Washington Heights, New York) was nominated for two Academy wrote for 98 various stories for film and television including Awards, once in 1942 for Best Actor in a Leading Role for Here Fantasy Island (TV Series, 11 episodes from 1978 - 1981), 1978 Comes Mr. -

The Rhetoric of the Benign Scapegoat: President Reagan and the Federal Government

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 The Rhetoric of the Benign Scapegoat: President Reagan and the Federal Government. Stephen Wayne Braden Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Braden, Stephen Wayne, "The Rhetoric of the Benign Scapegoat: President Reagan and the Federal Government." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7340. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7340 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

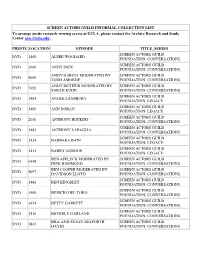

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST to Arrange Onsite Research Viewing Access at UCLA, Please Contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected]

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST To arrange onsite research viewing access at UCLA, please contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected] . PREFIX LOCATION EPISODE TITLE_SERIES SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1460 ALFRE WOODARD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1669 ANDY DICK FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY GARCIA MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8699 TODD AMORDE FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY RICHTER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7020 SARAH KUHN FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1484 ANGLE LANSBURY FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1409 ANN DORAN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 2010 ANTHONY HOPKINS FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1483 ANTHONY LAPAGLIA FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1434 BARBARA BAIN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1413 BARRY GORDON FOUNDATION: LEGACY BEN AFFLECK MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 6348 PETE HAMMOND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BEN COOPER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8697 DAVIDSON LLOYD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1486 BEN KINGSLEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1500 BENICIO DEL TORO FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1674 BETTY GARRETT FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1416 BEVERLY GARLAND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL AND SUSAN SEAFORTH SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1843 HAYES FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL PAXTON MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7019 JENELLE RILEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS