Bw1 Foia Cbp 008407 1:454,000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extrapolating Demography with Climate, Proximity and Phylogeny: Approach with Caution

! ∀#∀#∃ %& ∋(∀∀!∃ ∀)∗+∋ ,+−, ./ ∃ ∋∃ 0∋∀ /∋0 0 ∃0 . ∃0 1##23%−34 ∃−5 6 Extrapolating demography with climate, proximity and phylogeny: approach with caution Shaun R. Coutts1,2,3, Roberto Salguero-Gómez1,2,3,4, Anna M. Csergő3, Yvonne M. Buckley1,3 October 31, 2016 1. School of Biological Sciences. Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science. The University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia. 2. Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Western Bank, Sheffield, UK. 3. School of Natural Sciences, Zoology, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland. 4. Evolutionary Demography Laboratory. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research. Rostock, DE-18057, Germany. Keywords: COMPADRE Plant Matrix Database, comparative demography, damping ratio, elasticity, matrix population model, phylogenetic analysis, population growth rate (λ), spatially lagged models Author statement: SRC developed the initial concept, performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RSG helped develop the initial concept, provided code for deriving de- mographic metrics and phylogenetic analysis, and provided the matrix selection criteria. YMB helped develop the initial concept and advised on analysis. All authors made substantial contributions to editing the manuscript and further refining ideas and interpretations. 1 Distance and ancestry predict demography 2 ABSTRACT Plant population responses are key to understanding the effects of threats such as climate change and invasions. However, we lack demographic data for most species, and the data we have are often geographically aggregated. We determined to what extent existing data can be extrapolated to predict pop- ulation performance across larger sets of species and spatial areas. We used 550 matrix models, across 210 species, sourced from the COMPADRE Plant Matrix Database, to model how climate, geographic proximity and phylogeny predicted population performance. -

Water Resources-Reconnaissance Series Report 54

STATE OF NEVADA ·DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WATER RESOURCES Carson City / Photograph by Lawrence Radiation Laboratory· Sedan Crater was formed in the dry a ll uv ium of Yucca Flat by on underground atomic detonation. WATER RESOURCES-RECONNAISSANCE SERIES REPORT 54 REGIONAL GROUND-WATER SYSTEMS IN THE NEVADA TEST SITE AREA, NYE, LINCOLN, AND CLARK COUNTIES, NEVADA By F. Eugene Rush Prepared cooperatively by the Geological Survey, U.S. Department of the Interior 1970 WATER RESOURCES - RECONNAISSANCE: SEJUES REPORT 54 ·. REGIONAL GROUND-WATER SYSTEMS·IN THE NEVADA TEST SITE AREA, NYE, LINCOLN, AND CLARK COUN'riE:S, NEVADA By F. Eugene Rush PreparBd cooperatively by the Geological Survey, u.s. Department of the Interior 1971 -\ FOREWORD The progr~m of reconnaissance water-resources studies was authorized by the 1960 Legislature to be carried on by Division of Water Resources of the Departc.ment of· Conservation and Natural Resources in cooperation with the u.s. Geological Survey. This report is the 54th in the series to be prepared by the staff of the Nevada District Office of the U.S. Geological Survey. These 54 reports describe the hydrology of 185 valleys. The reconnaissance surveys make available pertinent information of great and immediate value to many State and Federal agencies, the State cooperating agency, and the public. As development takes place in any area, ,]c,,mands for more detailed information will arise, and studies to supply such information will be undertaken. In the meantime, these reconnaissance studies are timely and adequately In<'eet tlle immediate needs for information on the wate.r resources of the areas covered by the reports. -

Cottontail Rabbits

Cottontail Rabbits Biology of Cottontail Rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.) as Prey of Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the Western United States Photo Credit, Sky deLight Credit,Photo Sky Cottontail Rabbits Biology of Cottontail Rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.) as Prey of Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the Western United States U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Regions 1, 2, 6, and 8 Western Golden Eagle Team Front Matter Date: November 13, 2017 Disclaimer The reports in this series have been prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) Western Golden Eagle Team (WGET) for the purpose of proactively addressing energy-related conservation needs of golden eagles in Regions 1, 2, 6, and 8. The team was composed of Service personnel, sometimes assisted by contractors or outside cooperators. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Suggested Citation Hansen, D.L., G. Bedrosian, and G. Beatty. 2017. Biology of cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.) as prey of golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the western United States. Unpublished report prepared by the Western Golden Eagle Team, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Available online at: https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/Reference/Profile/87137 Acknowledgments This report was authored by Dan L. Hansen, Geoffrey Bedrosian, and Greg Beatty. The authors are grateful to the following reviewers (in alphabetical order): Katie Powell, Charles R. Preston, and Hillary White. Cottontails—i Summary Cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.; hereafter, cottontails) are among the most frequently identified prey in the diets of breeding golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the western United States (U.S.). -

Floristic Surveys of Saguaro National Park Protected Natural Areas

Floristic Surveys of Saguaro National Park Protected Natural Areas William L. Halvorson and Brooke S. Gebow, editors Technical Report No. 68 United States Geological Survey Sonoran Desert Field Station The University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona USGS Sonoran Desert Field Station The University of Arizona, Tucson The Sonoran Desert Field Station (SDFS) at The University of Arizona is a unit of the USGS Western Ecological Research Center (WERC). It was originally established as a National Park Service Cooperative Park Studies Unit (CPSU) in 1973 with a research staff and ties to The University of Arizona. Transferred to the USGS Biological Resources Division in 1996, the SDFS continues the CPSU mission of providing scientific data (1) to assist U.S. Department of Interior land management agencies within Arizona and (2) to foster cooperation among all parties overseeing sensitive natural and cultural resources in the region. It also is charged with making its data resources and researchers available to the interested public. Seventeen such field stations in California, Arizona, and Nevada carry out WERC’s work. The SDFS provides a multi-disciplinary approach to studies in natural and cultural sciences. Principal cooperators include the School of Renewable Natural Resources and the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at The University of Arizona. Unit scientists also hold faculty or research associate appointments at the university. The Technical Report series distributes information relevant to high priority regional resource management needs. The series presents detailed accounts of study design, methods, results, and applications possibly not accommodated in the formal scientific literature. Technical Reports follow SDFS guidelines and are subject to peer review and editing. -

The AZNPS Led Waterman Restoration Project: Helping the Sonoran Upland Desert to Heal Itself

The AZNPS Led Waterman Restoration Project: Helping the Sonoran Upland Desert to Heal Itself John Scheuring Arizona Native Plant Society, Tucson Chapter [email protected] The Setting The Waterman Mountains are a rare limestone desert uplift 30 miles northwest of Central Tucson within the confines of the Ironwood Forest National Monument (IFNM) and administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). The Waterman’s are home to several alkali loving plants including the federally listed endangered species the Nichol's Turk’s head cactus (Echinocactus horizonthalonius var. nicholi), elephant tree (Bursera microphylla), ocotillo (Fouqueria splendens) and desert agave (Agave deserti). The Waterman bajadas are dominated by saguaros (Carnegiea gigantea), foothill palo verdes (Parkinsonia microphyllum), and ironwood trees (Olnea tesote) with an understory of diverse grasses, forbs, and cacti. Desert bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis ssp. nelsoni), desert tortoise (Gopherus morafkai), as well as many species of desert birds thrive in the Watermans. Land Disturbance and Invasive Introduction In March 1981 Harlow Jones, a mining entrepreneur and small aircraft salesman, illegally bulldozed 18 acres of undisturbed desert bajada on the northwest side of the Watermans. The disturbance included a one-kilometer airstrip. Starting in 1982 Mr. Jones lived on-site with his family, until he was declared a trespasser by BLM in 1997 and forced to leave. BLM requested that Mr. Jones plant vegetation on the disturbed land. Mr. Jones responded by planting buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare). By 2005 the entire 18 acres as well as 10 acres of peripheral desert were heavily infested with buffelgrass. Initial Attempts To Control Buffelgrass There were recurrent efforts to control the buffelgrass. -

Biogenic Volatile Organic Compound Emissions from Desert Vegetation of the Southwestern US

ARTICLE IN PRESS Atmospheric Environment 40 (2006) 1645–1660 www.elsevier.com/locate/atmosenv Biogenic volatile organic compound emissions from desert vegetation of the southwestern US Chris Gerona,Ã, Alex Guentherb, Jim Greenbergb, Thomas Karlb, Rei Rasmussenc aUnited States Environmental Protection Agency, National Risk Management Research Laboratory, Research Triangle Park, NC 27711, USA bNational Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO 80303, USA cOregon Graduate Institute, Portland, OR 97291, USA Received 27 July 2005; received in revised form 25 October 2005; accepted 25 October 2005 Abstract Thirteen common plant species in the Mojave and Sonoran Desert regions of the western US were tested for emissions of biogenic non-methane volatile organic compounds (BVOCs). Only two of the species examined emitted isoprene at rates of 10 mgCgÀ1 hÀ1or greater. These species accounted for o10% of the estimated vegetative biomass in these arid regions of low biomass density, indicating that these ecosystems are not likely a strong source of isoprene. However, isoprene emissions from these species continued to increase at much higher leaf temperatures than is observed from species in other ecosystems. Five species, including members of the Ambrosia genus, emitted monoterpenes at rates exceeding 2 mgCgÀ1 hÀ1. Emissions of oxygenated compounds, such as methanol, ethanol, acetone/propanal, and hexanol, from cut branches of several species exceeded 10 mgCgÀ1 hÀ1, warranting further investigation in these ecosystems. Model extrapolation of isoprene emission measurements verifies recently published observations that desert vegetation is a small source of isoprene relative to forests. Annual and daily total model isoprene emission estimates from an eastern US mixed forest landscape were 10–30 times greater than isoprene emissions estimated from the Mojave site. -

Approved Plant Species (By Watershed) for Use in Riparian Mitigation Areas, Pima County, Arizona

APPROVED PLANT SPECIES (BY WATERSHED) FOR USE IN RIPARIAN MITIGATION AREAS, PIMA COUNTY, ARIZONA Western Pima County Botanical Name Common Name Life Form Water Requirements HYDRORIPARIAN TREES Celtis laevigata (Celtis reticulata) Netleaf/Canyon hackberry Perennial Tree Moderate Populus fremontii ssp. fremontii Fremont cottonwood Perennial Tree High Salix gooddingii Goodding’s willow Perennial Tree High SHRUBS Celtis ehrenbergiana (Celtis pallida) Desert hackberry, spiny hackberry Perennial Shrub Low GRASSES Plains bristlegrass, large-spike Setaria macrostachya Perennial Bunchgrass Moderate bristlegrass Sporobolus airoides Alkali sacaton Perennial Bunchgrass Moderate MESORIPARIAN TREES Acacia constricta Whitethorn Acacia Perennial shrub/small tree Low-moderate Acacia greggii Catclaw Acacia Perennial Tree Low Celtis laevigata (Celtis reticulata) Netleaf/Canyon hackberry Perennial Tree Moderate Chilopsis linearis Desert Willow Perennial Tree Moderate Parkinsonia florida Blue Palo Verde Perennial Tree Low- Moderate Populus fremontii ssp. fremontii Fremont cottonwood Perennial Tree High Prosopis pubescens Screwbean mesquite Perennial Tree Moderate Prosopis velutina Velvet mesquite Perennial Tree Low Salix gooddingii Goodding’s willow Perennial Tree High SHRUBS Anisacanthus thurberi (Drejera thurberi) Desert honeysuckle Perennial Shrub Moderate Celtis ehrenbergiana (Celtis pallida) Desert hackberry, spiny hackberry Perennial Shrub Low Lycium andersonii var. andersonii Anderson Wolfberry, water jacket Perennial Shrub Low Fremont Wolfberry, Fremont's -

ASTERACEAE Christine Pang, Darla Chenin, and Amber M

Comparative Seed Manual: ASTERACEAE Christine Pang, Darla Chenin, and Amber M. VanDerwarker (Completed, April 17, 2019) This seed manual consists of photos and relevant information on plant species housed in the Integrative Subsistence Laboratory at the Anthropology Department, University of California, Santa Barbara. The impetus for the creation of this manual was to enable UCSB graduate students to have access to comparative materials when making in-field identifications. Most of the plant species included in the manual come from New World locales with an emphasis on Eastern North America, California, Mexico, Central America, and the South American Andes. Published references consulted1: 1998. Moerman, Daniel E. Native American ethnobotany. Vol. 879. Portland, OR: Timber press. 2009. Moerman, Daniel E. Native American medicinal plants: an ethnobotanical dictionary. OR: Timber Press. 2010. Moerman, Daniel E. Native American food plants: an ethnobotanical dictionary. OR: Timber Press. Species included herein: Achillea lanulosa Achillea millefolium Ambrosia chamissonis Ambrosia deltoidea Ambrosia dumosa Ambrosia eriocentra Ambrosia salsola Artemisia californica Artemisia douglasiana Baccharis pilularis Baccharis spp. Bidens aurea Coreopsis lanceolata Helianthus annuus 1 Disclaimer: Information on relevant edible and medicinal uses comes from a variety of sources, both published and internet-based; this manual does NOT recommend using any plants as food or medicine without first consulting a medical professional. Achillea lanulosa Family: Asteraceae Common Names: Yarrow, California Native Yarrow, Common Yarrow, Western Yarrow, Mifoil Habitat and Growth Habit: This plant is distributed throughout the Northern Hemisphere. It is native in temperate areas of North America. There are both native and introduced species in areas creating hybrids. Human Uses: This plant has a positive fragrance making it desired in gardens. -

List of Approved Plants

APPENDIX "X" – PLANT LISTS Appendix "X" Contains Three (3) Plant Lists: X.1. List of Approved Indigenous Plants Allowed in any Landscape Zone. X.2. List of Approved Non-Indigenous Plants Allowed ONLY in the Private Zone or Semi-Private Zone. X.3. List of Prohibited Plants Prohibited for any location on a residential Lot. X.1. LIST OF APPROVED INDIGENOUS PLANTS. Approved Indigenous Plants may be used in any of the Landscape Zones on a residential lot. ONLY approved indigenous plants may be used in the Native Zone and the Revegetation Zone for those landscape areas located beyond the perimeter footprint of the home and site walls. The density, ratios, and mix of any added indigenous plant material should approximate those found in the general area of the native undisturbed desert. Refer to Section 8.4 and 8.5 of the Design Guidelines for an explanation and illustration of the Native Zone and the Revegetation Zone. For clarity, Approved Indigenous Plants are considered those plant species that are specifically indigenous and native to Desert Mountain. While there may be several other plants that are native to the upper Sonoran Desert, this list is specific to indigenous and native plants within Desert Mountain. X.1.1. Indigenous Trees: COMMON NAME BOTANICAL NAME Blue Palo Verde Parkinsonia florida Crucifixion Thorn Canotia holacantha Desert Hackberry Celtis pallida Desert Willow / Desert Catalpa Chilopsis linearis Foothills Palo Verde Parkinsonia microphylla Net Leaf Hackberry Celtis reticulata One-Seed Juniper Juniperus monosperma Velvet Mesquite / Native Mesquite Prosopis velutina (juliflora) X.1.2. Indigenous Shrubs: COMMON NAME BOTANICAL NAME Anderson Thornbush Lycium andersonii Barberry Berberis haematocarpa Bear Grass Nolina microcarpa Brittle Bush Encelia farinosa Page X - 1 Approved - February 24, 2020 Appendix X Landscape Guidelines Bursage + Ambrosia deltoidea + Canyon Ragweed Ambrosia ambrosioides Catclaw Acacia / Wait-a-Minute Bush Acacia greggii / Senegalia greggii Catclaw Mimosa Mimosa aculeaticarpa var. -

Phoenix Active Management Area Low-Water-Use/Drought-Tolerant Plant List

Arizona Department of Water Resources Phoenix Active Management Area Low-Water-Use/Drought-Tolerant Plant List Official Regulatory List for the Phoenix Active Management Area Fourth Management Plan Arizona Department of Water Resources 1110 West Washington St. Ste. 310 Phoenix, AZ 85007 www.azwater.gov 602-771-8585 Phoenix Active Management Area Low-Water-Use/Drought-Tolerant Plant List Acknowledgements The Phoenix AMA list was prepared in 2004 by the Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR) in cooperation with the Landscape Technical Advisory Committee of the Arizona Municipal Water Users Association, comprised of experts from the Desert Botanical Garden, the Arizona Department of Transporation and various municipal, nursery and landscape specialists. ADWR extends its gratitude to the following members of the Plant List Advisory Committee for their generous contribution of time and expertise: Rita Jo Anthony, Wild Seed Judy Mielke, Logan Simpson Design John Augustine, Desert Tree Farm Terry Mikel, U of A Cooperative Extension Robyn Baker, City of Scottsdale Jo Miller, City of Glendale Louisa Ballard, ASU Arboritum Ron Moody, Dixileta Gardens Mike Barry, City of Chandler Ed Mulrean, Arid Zone Trees Richard Bond, City of Tempe Kent Newland, City of Phoenix Donna Difrancesco, City of Mesa Steve Priebe, City of Phornix Joe Ewan, Arizona State University Janet Rademacher, Mountain States Nursery Judy Gausman, AZ Landscape Contractors Assn. Rick Templeton, City of Phoenix Glenn Fahringer, Earth Care Cathy Rymer, Town of Gilbert Cheryl Goar, Arizona Nurssery Assn. Jeff Sargent, City of Peoria Mary Irish, Garden writer Mark Schalliol, ADOT Matt Johnson, U of A Desert Legum Christy Ten Eyck, Ten Eyck Landscape Architects Jeff Lee, City of Mesa Gordon Wahl, ADWR Kirti Mathura, Desert Botanical Garden Karen Young, Town of Gilbert Cover Photo: Blooming Teddy bear cholla (Cylindropuntia bigelovii) at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monutment. -

Ar Iz Onautah California Cal If Orn Ia Oregon Idaho

DESIGNATED GROUNDWATER BASINS OF NEVADA £ * # £ 47N £ £ J OREGON IDAHO k a 11 e Jackpot r 18E 19E 10 24E 25E e b 20E 21E 5 McDermitt r 47N Denio £ 22E 26E 28E i 23E C 27E d E E Owyhee g e 2 2 68E 69E 70E / / 1 66E 67E 1 55E 6 1 47N 63E 64E 65E 4 46N 3 44E 46E 49E 50E 51E 52E 53E 57E 59E 60E 61E 62E 45E 47E 48E 5 2 54E 47N 56E 58E 30E 31E 32E 33E s 140 34E 35E 38E 41E B l 36E 37E 39E l 13 U 40E 42E 43E ru C V a K n a r e n F i R 46N n e a y g 39 o v u Mountain i n s i v 41 R 12 R e iv r Jarbidge Peak City e * 45N 2 *Capitol Peak 34 46N r 46N * Matterhorn C O re w ek 45N No y Copper Mtn. rth h n Fo e * o R rk e 33B 37 lm i L R a 44N v it 45N S 30A e t iv 4 140 r le e VU r 7 45N H u m Sun C 44N n bo 38 reek n ld 0 i t 40 u 68 9 Q Granite Peak 35 Wildhorse 44N 1 43N 33A * 8 3 29 Reservoir 9 44N 43N Vya U M a r 42N 43N ys Orovada* Santa Rosa Peak 30B 43N T 42N 27 *McAfee Peak 14 67 41N *Jacks Peak 42N A R S N 42N out h i F o v 41N e o r r r k t h 189B 189C L i 189A H t t l 40N Chimney e 41N 15 F 41N H Reservoir o u r r 25 e m k Tecoma v 42 40N i b 44 R o l d Humboldt t 36 R 40N i 39N 69 v r e 40N r e 93 v H U M B O L D T i £ 26 ¤ 189D 39N R t Montello ld 63 o b 39N 32 m R 38N 39N u E Li K O v 233 H e VU r 38N e 225 n l t VU in t u i Q ¤£95 L 31 38N 38N 66 Cobre 37N 16 37N Wells Ma 28 gg 80 ie ¨¦§ 37N Pilot Peak* A 37N Oasis 36N 36N C I r R e 93 e o ¤£ k c k 36N * Hole in the 36N Mtn. -

Nevada Hydrographic Areas and Sub-Areas/Listed Alphabetically by Primary County of Location Basin Area Area Area Num

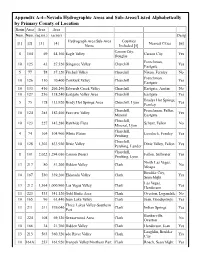

Appendix A-4--Nevada Hydrographic Areas and Sub-Areas/Listed Alphabetically by Primary County of Location Basin Area Area Area Num. Num. (sq.mi.) (acres) Desig Hydrograph Area/Sub-Area Counties [1] [2] [3] [4] Nearest Cities [6] Name Included [5] Carson City, 8 104 69 44,160 Eagle Valley Carson City Yes Douglas Frenchman, 10 125 43 27,520 Stingaree Valley Churchill Yes Eastgate 5 77 58 37,120 Fireball Valley Churchill Nixon, Fernley No Frenchman, 10 126 110 70,400 Cowkick Valley Churchill Yes Eastgate 10 133 416 266,240 Edwards Creek Valley Churchill Eastgate, Austin No 10 127 216 138,240 Eastgate Valley Area Churchill Eastgate Yes Bradys Hot Springs, 5 75 178 113,920 Brady Hot Springs Area Churchill, Lyon Yes Fernley Churchill, Frenchman, Fallon, 10 124 285 182,400 Fairview Valley Yes Mineral Eastgate Churchill, 10 123 227 145,280 Rawhide Flats Schurz, Fallon No Mineral, Lyon Churchill, 4 74 164 104,960 White Plains Lovelock, Fernley Yes Pershing Churchill, 10 128 1,303 833,920 Dixie Valley Dixie Valley, Fallon Yes Pershing, Lander Churchill, 8 101 2,022 1,294,080 Carson Desert Fallon, Stillwater Yes Pershing, Lyon North Las Vegas, 13 217 80 51,200 Hidden Valley Clark No Moapa Boulder City, 10 167 530 339,200 Eldorado Valley Clark Yes Searchlight Las Vegas, 13 212 1,564 1,000,960 Las Vegas Valley Clark Yes Henderson 13 223 533 341,120 Gold Butte Area Clark Overton, Logandale No 10 165 96 61,440 Jean Lake Valley Clark Jean, Goodsprings Yes Three Lakes Valley-Southern 13 211 311 199,040 Clark Indian Springs Yes Part Bunkerville, 13 224