Regional Planning for Socio-Economic Development in Meerut District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Population Statistics, 4-Meerut, Uttar Pradesh

I Census of India, 195 1 DISTRICT POPULATION STATISTICS UTTAR PRADESH 4-MEEl{UT DISTRICT 315.42 ALLAHABAD: TING AND STATIONERY, UTTAR PRADESH, INDIA 1951 1952 MEE DPS Price, Re.1-S. FOREWORD THE Uttar Pradesh Government asked me in March. 1952, (0 'supply them for the purposes of elections to local bodies population statistics with ,separation for scheduled castes (i) mohalla/ward-wise for urban areas, and (ii) village-wise for rural areas. The Census Tabulation Plan did nbt provide for sorting of scheduled cast<;s population for areas smaller than a tehsil or urban tract and the request from the Uttar Pradesh Government came when the slip sorting had been finished and (he Tabulation Offices closed. As the census slips are mixed up for the purposes of sorting in one lot for a tehsil or urban tract, collection of data regarding scheduled castes population by moh'allas/wards and villages would have involved enormous labour and expense if sorting of the slips had been taken up afresh. Fortunately, however, a secondary census record, viz. the National Citizens' Register, in which each slip has been copied, was available. By singular foresight it had been pre pared mohalla/ward-wise for urban areas and village-wise for rural areas. Th e required information has, therefore. been extracted from. this record, 2. In the above circumstances there is a slight difference in the figures of population as arrived at by an earlier sorting of the slips and as now determined by counting from the National Citizens' Register. This difference has been accen mated by an order passed by me during the later coum from the National Register of Citizens as follows:- (i) Count Ahirwars of Farrukhabad District, Raidas and Bhagar as ·Chamars'. -

LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 1326 to BE ANSWERED on 10.02.2020 REGARDING PROMOTION of CNG and PNG List of Geographical Areas Covered Till 10Th CGD Bidding Round

LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 1326 TO BE ANSWERED ON 10.02.2020 Promotion of CNG and PNG 1326. SHRI SANGAM LAL GUPTA: SHRI RAMDAS C. TADAS: पेट्रोलियम और प्राकृलिक गैस मंत्री Will the Minister of PETROLEUM AND NATURAL GAS be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government proposes to promote the use of CNG and PNG to control pollution; (b) if so, the cities of Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra which have been connected to CNG and PNG supply so far along with the cities proposed to be connected in the near future; (c) whether the Government proposes to connect Pratapgarh in Uttar Pradesh and Wardha and Amravati in Maharashtra with CNG and PNG supply by opening CNG and PNG stations there; (d) if so, the details thereof along with the time by which it is likely to be done; and (e) if not, the reasons therefor? ANSWER पेट्रोलियम और प्राकृलिक गैस मंत्री (श्री धमेन्द्र प्रधान) MINISTER OF PETROLEUM AND NATURAL GAS (SHRI DHARMENDRA PRADHAN) (a) : Government has taken a series of decisions to promote use of CNG and PNG. (b) to (e) : Development of City Gas Distribution (CGD) networks supports the availability and accessibility of natural gas in form of Piped Natural Gas (PNG) to households, industrial uses and Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) for transportation uses. Petroleum & Natural Gas Regulatory Board (PNGRB) is the authority to grant authorization to the entities for developing of CGD network in Geographical Areas (GAs) as per PNGRB Act, 2006. PNGRB identifies GAs for authorizing the development of CGD network in synchronization with the development of natural gas pipeline connectivity and natural gas availability. -

District Census Handbook, Meerut, Part X-A, Series-21, Uttar Pradesh

CENSUS 1971 PART X-A Tcr\VN< & VILLAGE DIRECTORY SERIES 21 UTTAR PRADESH DISTRICT. DISTRICT MEERUT CENSUS HANDBOOK D. M. SINHA OF THE i};DIAN AD1IlNISTRATIVE SERVICE Director of Census Operatiorn Uttar Pradesh DISTRICT MEERUT I 10 I) 10 KMS b:.u.=.:.- -± - - 1--±=:;d o ". IL- f- i ,<-lS 01STRICT 1l0UNOARY TAHSIL BOUNDARY 'YIKAS ~HflND IIOUNDARY DISTRICT HEAOQUARTERS TAHSIL HEA.OQUA.RnR~ I""" ~ VtKIS KHA.Ha H~AOQU"'fHkS .~".'"' ,." 10111101 OF THE DIITRICT o ,v • ,.~\ ',., IN UTTAR PRIOEIH URBAN IUfA f/ c'~"'\f/ IJ . ~ - \, ,. "\ VILI.AGE WITH POPULATION MI]lI Olt "1011£ • ~~,' :'\ 0 IO::J 200 .(\,~S HIGHWAYS. NA1'IONAL, ,TATE l~iltUL_ )..'1:) r'; ~ OTHER IMPORTANT ROAD' ' ____ .- I R.A1L'hAV UI\IE WITH STAttON. BROAD (iIl.UC.EI, __ "i~ .... _ Nome of the A,,, in IPoPUIO\iOn No." No. of NARROW"A.UGEI~_ ,\. Tahsil K.' Villagfs Towns v;:-.... RIVER AND 5TRfAH I " ........ '" ~),. BlGHPII 1,0lll 561,066 154 CANAL WI1l11MPORTANT DISTRIBUiflfW \ I GHIZIIBAD 1.0581 718.91J III POlICf STATION P5 IIROHINI 895·1 4\M11 106 ron & nLEG.RA~H OFFICe. I PI MEERUI 7110 141.B14 119 RtH HOUSi TRAVELLERS' BUNGALOW, HC, I RH 5" HAmA 1.098.4 J90.))5 l06 HOSPITAL, PlSPENSARY,P, H, CENnE, ETC + HAPUR 1.0811 516.73B ll, DEGREE (OLlEG£, H. S, SCHOOL 8,0 TOTAL 5,944.0 3,%6.951 1,651 22 L_·--~~~~~-o~,--------~------------~~------~----~----~---, , 77 15 East of Gr"cw", 30 ~5 CONTENTS Pages Acknowledgements Introductory Note iii TOWN AND VILLA.GE DIRECTORY Town Directory Statement I-Status, Growth History and Functional Category of Towns 4-5 Statement II-Physical Aspects -

List of Ph.D. Awarded

Geography Dept. B.H.U.: List of PhD awarded, 1958-2013 1 Updated: 19 August 2013: The 67th Geography Foundation Day B.H.U. Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, UP 221005. INDIA Department of Geography Doctoral Dissertation, Ph.D., in Geography: 1958 – 2013. No. Name of Scholar Title of the Doctoral Dissertation Awarded, & pub. year 1 2 3 4 1. Supervisor : Prof. Ram Lochan Singh (1946-1977) (late) 1. Shanti Lal Kayastha Himalayan Beas-Basin : A Study in Habitat, Economy 1958 and Society Pub. 1964 2. Radhika Narayan Ground Water Hydrology of Meerut District, U.P 1960 Mathur (earlier worked under Prof. Raj Nath, Geology Dept.) Pub. 1969 3. M. N. Nigam Urban Geography of Lucknow : (Submitted at Agra 1960 University) 4. S. L. Duggal Land Utilization Pattern in Moradabad District 1962 (submitted at Punjab University) 5. Vijay Ram Singh Land Utilization in the Neighbourhood of Mirzapur, U.P. 1962 Pub. 1970 6. Jagdish Singh Transport Geography of South Bihar 1962 Pub. 1964 7. Baccha Prasad Rao Vishakhapatanam : A Study in Geography of Port Town 1962 Pub. 1971 8. (Ms) Surinder Pannu Agro-Industrial Relationship in Saryupar Plain of U.P. 1962 9. Kashi N. Singh Rural Markets and Rurban Centres in Eastern U.P. 1963 10. Basant Singh Land Utilization in Chakia Tahsil, Varanasi 1963 11. Ram Briksha Singh Geography of Transport in U.P. 1963 Pub. 1966 12. S. P. Singh Bhagalpur : A Study in Regional Geography 1964 13. N. D. Bhattacharya Murshidabad : A Study in Settlement Geography 1965 14. Attur Ramesh TamiInadu Deccan: A Study. in Urban Geography 1965 15. -

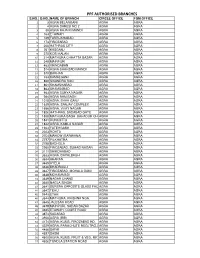

TOTAL PPF BRANCHES.Xlsx

PPF AUTHORISED BRANCHES S.NO. D.NO. NAME OF BRANCH CIRCLE OFFICE FGM OFFICE 1 3 AGRA BELANGANJ AGRA AGRA 2 4 AGRA DARESI NO 2 AGRA AGRA 3 30 AGRA RAJA KI MANDI AGRA AGRA 4 163 ETAWAH AGRA AGRA 5 169 FARRUKHABAD AGRA AGRA 6 173 FIROZABAD AGRA AGRA 7 200 HATHRAS CITY AGRA AGRA 8 261 KASGANJ AGRA AGRA 9 270 KOSI KALAN AGRA AGRA 10 314 MATHURA CHHATTA BAZAR AGRA AGRA 11 348 MAINPURI AGRA AGRA 12 463 VRINDABAN AGRA AGRA 13 514 AGRA SHAHZADI MANDI AGRA AGRA 14 570 BARHAN AGRA AGRA 15 733 KAMALGANJ AGRA AGRA 16 860 SIKANDRA RAO AGRA AGRA 17 861 SHAMSHABAD AGRA AGRA 18 863 SHAMSABAD AGRA AGRA 19 983 AGRA SURYA NAGAR AGRA AGRA 20 984 AGRA RAM BAGH AGRA AGRA 21 1018 AGRA, SHAH GANJ AGRA AGRA 22 1639 AGRA, SANJAY COMPLEX AGRA AGRA 23 1656 AGRA, VIJAY NAGAR AGRA AGRA 24 1826 HATHRAS, SADABAD GATE AGRA AGRA 25 1838 MATHURA BAGH BAHADUR CHOWKAGRA AGRA 26 1841 RUNKUTTA AGRA AGRA 27 1842 AGRA, KAMLA NAGAR AGRA AGRA 28 1934 FATEHGARH AGRA AGRA 29 2023 ROHTA AGRA AGRA 30 2754 MAHOW (BARWANA) AGRA AGRA 31 2797 PILKHATRA AGRA AGRA 32 2798 BADHOLA AGRA AGRA 33 2960 FIROZABAD, SUHAG NAGAR AGRA AGRA 34 3111 SHIKOHABAD AGRA AGRA 35 3633 AGRA, DAYALBAGH AGRA AGRA 36 3634 AHARAN AGRA AGRA 37 3635 AYELA AGRA AGRA 38 3636 BHADRAULI AGRA AGRA 39 3637 FIROZABAD, MOHALA GANJ AGRA AGRA 40 3638 MOHAMMADI AGRA AGRA 41 3639 NAGAR CHAND AGRA AGRA 42 3640 NAGLA SINGHI AGRA AGRA 43 3641 SURERA OPPOSITE GLASS FACTORYAGRA AGRA 44 3642 TEHU AGRA AGRA 45 3643 ETAH AGRA AGRA 46 3644 MATHURA, KRISHNA NGR. -

Integrated Milk Co-Operatives in North-West Uttar Pradesh: Organisation, Functioning and Performance

Ind. Jn. ofAgri. Econ. Vol.51, No.4, Oct.-Dec. 1996 Integrated Milk Co-operatives in North-West Uttar Pradesh: Organisation, Functioning and Performance V.P.S. Arora and T.S. 13hogal* The first co-operative activity in dairy enterprise in the country started with the orga- nisation of Katra Co-operative Milk Society in 1917 at Allahabad (Uttar Pradesh).In 1938, the Lucicnow Milk Producers' Union was established, followed by similar establishments at Allahabad(1941), Varanasi(1947), Kanpur (1948), Haldwani (1949), and Meerut(1950). To provide effective impetus to the dairy development programme in the state, the State Co-operative Dairy Federation was established in 1962. The Operation-Flood 1,11 and ifi schemes were launched in the state in 1970-71, 1982 and 1987 respectively. At present, about 60 districts of the state are covered under the dairy development programme of the co-operative sector. In this paper an attempt is made to analyse and present the organisational set-up,system of functioning and performance of integrated dairy co-operatives in the north-west region of Uttar Pradesh (U.P.). RESEARCH METHODOLOGY The study is conducted in the north-west region of U.P., well known for progressive development in agriculture and dairying. Through random sampling, Meerut district was selected for an in-depth study. From Meerut district, two blocks one having high concen- tration and the other having low concentration of milk animals per hectare of crop area were selected randomly. From each sample block six villages having a dairy co-operative and ten milk producers from each sample village were randomly selected for the study. -

Planning Proposals for Water Supply of U.P. Sub Region of Ncr

PLANNING PROPOSALS FOR WATER SUPPLY OF U.P. SUB REGION OF NCR A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MASTER OF URBAN AND RURAL PLANNING By MATINDER KUMAR DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE & PLANNING INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ROORKEE ROORKEE - 247 667 (INDIA) JUNE, 2007 CANDIDATE'S DECLARATION I hereby certify that the work, which is being presented in the dissertation, entitled "PLANNING PROPOSALS FOR WATER SUPPLY OF U.P. SUB REGION OF NCR", in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of the Degree of MASTER OF URBAN AND RURAL PLANNING submitted in the Department of Architecture and Planning, Indian Institute of Technology - Roorkee, is an authentic record of my own work carried out during the period from May 2006 to June 2007 under the supervision of Prof. R. K. Jain, Associate Professor, Department of Architecture and Planning, Indian Institute of Technology - Roorkee. The matter embodied in this dissertation has not been submitted by me for the award of any other Degree. Place: Roorkee ktrAihnkt Dated: June 2c12007 (Matinder Kumar) This is to certify that the above statement made by the candidate Mr. Matinder Kumar is correct to the best of my knowledge. Place: Roorkee Dated: June, 2007 (Prof. R. K. Jain) Associate Professor Department of Architecture and Planning Indian Institute of Technology - Roorkee Roorkee — 247667, India ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I take this opportunity to express my deep sense of gratitude to my respected guide Prof. R. K. Jain, Department of Architecture and Planning, Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee (Uttrakhand) for his constant encouragement, support and expert guidance throughout this work starting from choosing the topic. -

HIGH COURT of JUDICATURE at ALLAHABAD NOTIFICATION DATED: ALLAHABAD: July 02, 2015

HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT ALLAHABAD NOTIFICATION DATED: ALLAHABAD: July 02, 2015 No. 1284 / JR(S)/2015 Sri Shiv Dan Yadav, Additional District & Sessions Judge (Fast Track Court), Jalaun at Orai to be Additional District & Sessions Judge (Fast Track Court), Jalaun at Orai on promotion to U.P. Higher Judicial Service pursuant to U.P. Government Office Memo No. 8/2015/1111/II-4-2015-32(I)/2015 dated 26.6.2015. No. 1285 /JR(S)/2015 Pursuant to Government Office Memorandum No. 8/2015/1111/II-4-2015- 32(I)/2015 dated 26.6.2015., Sri Kunal Vepa, Advocate is appointed as direct recruit from the Bar to U.P. Higher Judicial Service and posted as Additional District & Sessions Judge, Ghaziabad. No. 1286 / JR(S)/2015 Sri Sham Kumar, Additional District & Sessions Judge (Fast Track Court), Banda to be Additional District & Sessions Judge (Fast Track Court), Banda on promotion to U.P. Higher Judicial Service pursuant to U.P. Government Office Memo No. 8/2015/1111/II-4-2015-32(I)/2015 dated 26.6.2015. No. 1287 / JR(S)/2015 Sri Mahendra Pratap Singh Yadav, Chief Judicial Magistrate, Mahoba to be Additional District & Sessions Judge, Mahoba on promotion to U.P. Higher Judicial Service pursuant to U.P. Government Office Memo No. 8/2015/1111/II-4-2015-32(I)/2015 dated 26.6.2015. No. 1288 / JR(S)/2015 Sri Mahesh Kumar Kushwaha, Judge Small Causes Court, Bareilly to be Additional District & Sessions Judge, Kaushambi on promotion to U.P. Higher Judicial Service pursuant to U.P. -

Folk Medicinal Uses of Plant Roots from Meerut District, Uttar Pradesh

Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge Vol. 8(2), April 2009, pp. 298-301 Folk medicinal uses of plant roots from Meerut district, Uttar Pradesh Amit Tomar Department of Botany, Meerut College, Meerut 250001, Uttar Pradesh E-mail: [email protected] Received 21 August 2006 revised 24 January 2008 The paper enumerates 39 medicinal plant species belonging to 39 genera and 28 families, which are used as folk medicine in the treatment of various ailments or diseases by the rural and common people of Meerut district. Keywords: Folk medicine, Medicinal plants, Vaidhya IPC Int. Cl. 8: A61K36/00, A61P1/04, A61P1/06, A61P9/14, A61P15/00, A61P21/00, A61P27/00, A61P29/00, A61P31/00, A61P31/12, A61P39/02 Indian Systems of Medicine derives many of their curative tools from plants 1. Reference to plants used as drugs are often found in old literature ( Atharveda, Charak Samhita, Sushruta Samhita , etc.). In spite of achievement of allopathic medicines the Indian Systems of Medicine still continue to provide medical cure to majority of the people on account of their cheaper cost and no side effects 2. Folklore use of medicinal plants from Trinidad; Gwalior forest circle, Madhya Pradesh; Chittor district, Andhra Pradesh; Dehradun; Amritsar; Yanandis of Sathyavedu Mandal; Chittor district, Andhra Pradesh; Barnawa in Baghpat district Uttar Pradesh; and Baghpat district of Uttar Pradesh have been reportd 3-12 . Methodology The Meerut District situated in the Upper Ganga– Fig. 1 ―Map of study area Yamuna doab lies between latitude 28˚ 60 and 29˚ 18 N and longitude 77˚ 7 and 78˚ 14 E. -

Chandauli District, U.P

GROUND WATER BROCHURE OF CHANDAULI DISTRICT, U.P. By A.K. Bhargava Scientist 'C' CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. CHANDAULI DISTRICT AT A GLANCE ..................3 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................6 2.0 CLIMATE AND RAINFALL ..................6 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND SOIL TYPES ..................7 4.0 GROUND WATER SCENARIO ..................9 5.0 GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ..................15 6.0 GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUES AND PROBLEMS ..................15 7.0 AWARENESS & TRAINING ACTIVITIES ..................15 8.0 AREA NOTIFIED BY CGWA / SGWA ..................15 9.0 RECOMMENDATIONS ..................16 1 PLATES: I. INDEX MAP OF CHANDAULI DISTRICT, U.P. II. PREMONSOON DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL MAP (2012) OF CHANDAULI DISTRICT, U.P. III. POSTMONSOON DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL MAP (2012) OF CHANDAULI DISTRICT, U.P. IV. CATEGORIZATION MAP OF CHANDAULI DISTRICT, U.P. 2 CHANDAULI DISTRICT AT GLANCE 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) : 2541 ii. Administrative Divisions : Number of Tehsils 3 Number of Blocks 9 Number of Villages 1637 iii. Population (as on 2011 census) : Male 1017905 Female 934851 Total 1952756 iv. Average Annual Rainfall (mm) : 1019.00 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major Physiographic Units : (i) Northern Alluvial Plain (ii) Southern Hilly Region Major Drainages : River Ganga, River Karamnasa, Chandraprabha 3. LAND USE (Ha.) a) Forest area : 77400 b) Net sown area : 133147 c) Area sown more than once : 88720 d) Gross area sown : 221867 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES : (i) Alluvial (ii) Residual c. Bhur or sand 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS (Ha.) Jayad : 350 Kharif : 121371 Rabi : 115733 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (Areas and Number of Structures) Ha. Dugwells : - Tubewells Govt. : 246 Tubewells Pvt. -

Uttar Pradesh BSAP

NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN, UTTAR PRADESH (U.P.) Coordinator Coordinated by: U. Dhar GBPIHED TEAM S.S. Samant Asha Tewari R.S. Rawal NBSAP, U.P. Members Dr. S.S. Samant Dr. B.S. Burphal DR. Ipe M. Ipe Dr. Arun Kumar Dr. A.K. Singh Dr. S.K. Srivastava Dr. A.K. Sharma Dr. K.N. Bhatt Dr. Jamal A. Khan Miss Pia Sethi Dr. Satthya Kumar Miss Reema Banerjee Dr. Gopa Pandey Dr. Bhartendu Prakash Dr. Bhanwari Lal Suman Dr. R.D. Dixit Mr. Sameer Sinha Prof. Ajay S. Rawat 1 Contributors B.S. Burphal Pia Sethi S.K. Srivastava K.N. Bhatt D.K. pande Jamal A. Khan A.K. Sharma 2 CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 . Brief background of the SAP 1.2 . Scope of the SAP 1.3 . Objectives of the SAP 1.4 . Contents of the SAP 1.5 . Brief description of the SAP CHAPTER 2. PROFILE OF THE AREA 2.6 . Geographical profile 2.7 . Socio- economic profile 2.8 . Political profile 2.9 . Ecological profile 2.10.Brief history CHAPTER 3. CURRENT (KNOWN) RANGE AND STATUS OF BIODIVERSITY 3.1. State of natural ecosystems and plant / animal species 3.2. State of agricultural ecosystems and domesticated plant/ animal species CHAPTER 4. STATEMENTS OF THE PROBLEMS RELATED TO BIODIVERSITY 4.1. Proximate causes of the loss of biodiversity 4.2. Root causes of the loss of biodiversity CHAPTER 5. MAJOR ACTORS AND THEIR CURRENT ROLES RELEVANT TO BIODIVERSITY 5.1. Governmental 5.2. Citizens’ groups and NGOs 5.3. Local communities, rural and urban 5.4. -

DISTRICTS COVERED 1. Mau 2. Chandauli 3. Fatehpur 4. Ghazipur

1 2ND HALF YEARLY MONITORING REPORT OF G.B. PANT SOCIAL SCIENCE INSTITUTE, ALLAHABAD ON SSA AND MDM FOR THE STATE/UT OF UTTAR PRADESH FOR THE PERIOD OF 1ST FEBRUARY, 2009 to 31 ST JULY, 2009 DISTRICTS COVERED 1. Mau 2. Chandauli 3. Fatehpur 4. Ghazipur 2 August 2009 R E P O R By S. K. Pant Submitted to Ministry of Human Resource Development, New Delhi G. B. Pant Social Science Institute Allahabad – 211 019 Phone: (0532) 2569214, 2569206, Fax: (0532) 2569207 3 Content Sl. No. Particulars Page Nos. 1. Forward 3 2. Acknowledgement 4 3. Project Team 5 4. General Information 6 - 7 5. Executive Summary of all the districts reports 8 - 24 6. Chapter - 1 Half Yearly Monitoring Report for District – 1 : Mau 25 - 55 7. Chapter - 2 Half Yearly Monitoring Report for District – 2 : Chandauli 56 - 87 8. Chapter - 3 Half Yearly Monitoring Report for District – 3 : Fatehpur 88 - 118 9. Chapter - 4 Half Yearly Monitoring Report for Distr ict – 4 : Ghazipur 119 - 150 10. List of Abbreviations 151 4 FOREWORD The Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan has a set of very specific targets for implementation. During the last three to four years, there have been several interventions under this programme and the progress and problems relating to the implementation of this programme have been analyzed and reviewed periodically at regional and at the national level. On the basis of the findings of these reviews and analysis, each State/UT has been allocated with some grants and manpower to conduct the programme related activities with more vigor and enthusiasm.