Anaphylaxis During the Perioperative Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactive Arthritis This Sheet Has Been Written for People Affected by Reactive Arthritis

ARTHRIINFORMATIONTI SHEETS ARTHRIINFORMATIONTI SHEETS Reactive arthritis This sheet has been written for people affected by reactive arthritis. It provides general information to help you understand how you may be affected. This sheet also covers how reactive arthritis usually resolves over time. What is reactive arthritis? It is not known why some people who get these Reactive arthritis is a condition that causes infections develop reactive arthritis and some do not. inflammation, pain and swelling of the joints. It usually A certain gene called HLA-B27 is associated with develops after an infection, often in the bowel or genital reactive arthritis, especially inflammation of the spine. areas. The infection causes activity in the immune However this is a perfectly normal gene and there are system. The normal role of your body’s immune system many more people who have this gene and do not get is to fight off infections to keep you healthy. In some reactive arthritis. people this activity of the immune system causes joints to become inflamed, however the joints themselves How is it diagnosed? are not actually infected. About one in 10 people with Your doctor will diagnose reactive arthritis from your specific types of infections will get reactive arthritis. symptoms and a physical examination. Your doctor may also order blood tests for inflammation, such as the What are the symptoms? erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive Reactive arthritis usually begins a few weeks after an protein (CRP) tests. Blood tests may also help to rule infection. Symptoms can affect many parts of the body out other types of arthritis. -

Confidential

CONFIDENTIAL CHILD’S MEDICAL INFORMATION The following is important information about my child’s medical condition and how the condition may affect their ability to fully participate in a regular school setting. The goal is to try to normalize every day school routines/activities while also meeting my child’s unique needs in the least disruptive manner. This document is not intended to replace any existing Individual Educational Plan (IEP) or the 504 Plan, but rather to serve as a supplement or addendum to enhance my child’s education. Medical information will be updated at the beginning of each new school year and throughout the school year as deemed necessary. “We may not look sick, but turn our bodies inside out and they will tell different stories.” Wade Sutherland CHILD’S NAME: ____________________________________________________________________________ ACADEMIC YEAR: _____________________GRADE: __________DOB: __________________AGE: _________ HOME ADDRESS: __________________________________________________________________________ PARENT/LEGAL GUARDIAN: ________________________________________________________________ PARENT/LEGAL GUARDIAN CONTACT NUMBER: ______________________________________________ SCHOOL: ________________________________________________________________________________ EMERGENCY CONTACT (2 PEOPLE) NAME: __________________________________________________________________________________ RELATIONSHIP: ____________________________ PHONE NUMBER: ________________________________ NAME: __________________________________________________________________________________ -

Reactive Arthritis

PATIENT FACT SHEET Reactive Arthritis Reactive arthritis is an inflammatory disease that Most often, these bacterial infections are in the genitals occurs in reaction to infections by certain bacteria. or bowels, including the sexually transmitted infection Arthritis may show up a month after the infection. Once Chlamydia trachomatis, and bowel infections like called Reiter’s syndrome, it is a “spondyloarthropathy.” Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella and Yersinia. Reactive arthritis often affects men between 20 and CONDITION 50. It’s usually short in duration, but can be chronic in some people. DESCRIPTION Reactive arthritis symptoms include pain and swelling discharge from the genitals, but a urine or genital swab in knees, ankles or heels; severe swelling of toes or test can show signs of this infection. Bowel infections fingers; and persistent lower back pain that tends to may cause diarrhea. be more severe at night or in the morning. It may cause Most people with these very common infections irritated, red eyes, burning during urination, or a rash on don’t get reactive arthritis. People who test positive for the palms or soles of the feet. the HLA-B27 gene may be at higher risk for severe or To diagnose reactive arthritis, a rheumatologist may chronic arthritis, but those who test negative may get SIGNS/ look for these symptoms as well as signs of the original reactive arthritis too. People with weakened immune SYMPTOMS infection. Chlamydia may cause watery or pus-like systems from HIV or AIDS may develop reactive arthritis. Effective treatments are available for reactive arthritis. Later-stage, or chronic reactive arthritis, may be It is treated according to how far the disease has treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs progressed. -

Reactive Arthritis Information Booklet

Reactive arthritis Reactive arthritis information booklet Contents What is reactive arthritis? 4 Causes 5 Symptoms 6 Diagnosis 9 Treatment 10 Daily living 16 Diet 18 Complementary treatments 18 How will reactive arthritis affect my future? 19 Research and new developments 20 Glossary 20 We’re the 10 million people living with arthritis. We’re the carers, researchers, health professionals, friends and parents all united in Useful addresses 25 our ambition to ensure that one day, no one will have to live with Where can I find out more? 26 the pain, fatigue and isolation that arthritis causes. Talk to us 27 We understand that every day is different. We know that what works for one person may not help someone else. Our information is a collaboration of experiences, research and facts. We aim to give you everything you need to know about your condition, the treatments available and the many options you can try, so you can make the best and most informed choices for your lifestyle. We’re always happy to hear from you whether it’s with feedback on our information, to share your story, or just to find out more about the work of Versus Arthritis. Contact us at [email protected] Registered office: Versus Arthritis, Copeman House, St Mary’s Gate, Chesterfield S41 7TD Words shown in bold are explained in the glossary on p.20. Registered Charity England and Wales No. 207711, Scotland No. SC041156. Page 2 of 28 Page 3 of 28 Reactive arthritis information booklet What is reactive arthritis? However, some people find it lasts longer and can have random flare-ups years after they first get it. -

Rheumatic Fever and Post-Streptococcal Reactive Arthritis Version of 2016

https://www.printo.it/pediatric-rheumatology/IE/intro Rheumatic Fever And Post-streptococcal Reactive Arthritis Version of 2016 4. POST-STREPTOCOCCAL REACTIVE ARTHRITIS 4.1 What is it? Cases of streptococcal-associated arthritis have been described both in children and young adults. It is usually called "reactive arthritis" or "post-streptococcal reactive arthritis" (PSRA). PSRA commonly affects children between 8 to 14 years of age and young adults between 21 to 27 years. It usually develops within 10 days after a throat infection. If differs from arthritis of acute rheumatic fever (ARF), which mainly involves large joints. In PSRA, large and small joints and the axial skeleton are involved. It usually lasts longer than ARF — about 2 months, sometimes longer. Low grade fever might be present, with abnormal laboratory tests indicating inflammation (C reactive protein and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate). The inflammatory markers are lower than in ARF. The diagnosis of PSRA relies on arthritis with evidence of recent streptococcal infection, abnormal streptococcal antibody tests (ASO, DNAse B) and the absence of the signs and symptoms in a diagnosis of ARF according to "Jones criteria". PSRA is a different entity to ARF. PSRA patients will probably not develop carditis. Currently, the American Heart Association recommends prophylactic antibiotics for one year after symptoms onset. In addition, these patients should be carefully observed for clinical and echocardiographic evidence of carditis. If heart disease appears, the patient should be treated as in ARF; otherwise prophylaxis can be discontinued. Follow-up with a cardiologist is recommended. 1 / 2 2 / 2 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org). -

Reactivation of Inflammatory Monoarthritis During Dupilumab Treatment Used for Prurigo Nodularis

Arch Rheumatol 2022;37(x):i-ii doi: 10.46497/ArchRheumatol.2022.8780 LETTER TO THE EDITOR Reactivation of inflammatory monoarthritis during dupilumab treatment used for prurigo nodularis Ecem Bostan1, Duygu Gülseren1, Zehra Özsoy2, Fatma Bilge Ergen3 1Department of Dermatology, Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey 2Department of Internal Diseases, Division of Rheumatology, Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey 3Department of Radiology, Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey Dupilumab is a humanized monoclonal dupilumab. Although her clinical manifestations antibody which specifically targets interleukin-4/ and pruritus improved, she developed mild right interleukin-13 receptor and is primarily indicated for knee swelling, warmness, and arthralgia after the the treatment of atopic dermatitis, although it has first maintenance dose following the loading dose. been shown to be efficacious in various disorders Upon questioning, we recognized that the patient including asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis, prurigo developed reactive arthritis in the right knee, nodularis.1 Herein, we report an extraordinary when she was 10 years old. Until now, she stayed case related to the exacerbation of inflammatory asymptomatic. She was consulted to rheumatology arthritis in a patient under dupilumab treatment department and effusion was detected by right for prurigo nodularis. knee ultrasonography and arthrocentesis was performed which revealed no bacterial growth. An 18-year-old woman with a history of allergic Elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte rhinitis and atopic dermatitis, presented for her sedimentation levels were noted. Rheumatological pruritic lesions. The pruritic nodules started from markers were all negative. Right knee magnetic the lumbar area nine years ago and subsequently resonance imaging showed moderate effusion spread to entire body. -

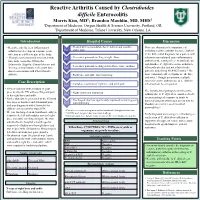

Reactive Arthritis Caused by Clostridium Difficile Enterocolitis

Reactive Arthritis Caused by Clostridioides difficile Enterocolitis Morris Kim, MD1; Brandon Mauldin, MD, MHS2 1Department of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR 2Department of Medicine, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA Introduction DiagnosticHospital Workup Course Discussion • Reactive arthritis is an inflammatory • Treated with metronidazole for C. difficile and possible This case illustrates the importance of arthritis that develops in response to an Day 1 septic joint including reactive arthritis due to C. difficile infection in a different part of the body. in the differential diagnosis for a patient with • New onset pain and swelling of right elbow otherwise unexplained acute inflammatory • Though most commonly associated with Day 3 infections caused by Chlamydia, arthritis in the setting of recent antibiotic use Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, and and diarrhea. C. difficile reactive arthritis is • New onset pain and swelling of left elbow, wrist, and knee Yersinia, a small number of reports have Day 4 often polyarticular and not related to the shown association with Clostridioides patient’s underlying HLA-B27 status.1 The difficile. • Right knee and ankle pain improving most commonly affected joints are the knee Day 7 and wrist.1 Though uncommon, multiple Case Description cases of reactive arthritis due to C. difficile • Complete resolution of right knee and ankle pain infection have been reported. Day 8 • 40-year-old man with a history of gout The hypothesized pathogenesis of reactive presented to the ED with swelling and pain • Right elbow pain improving in his right knee and ankle. Day 9 arthritis due to C. difficile is considered to be • an immunological response in joints to Earlier that day, he presented to the ED with • Discharged: diarrhea significantly improved; remaining joint five days of diarrhea and abdominal pain bacterial antigens which gain access into the Day 11 pain improving bloodstream via increased intestinal and was diagnosed with Clostridioides 2 difficile enterocolitis by stool PCR. -

Rheumatology

Clinical Telehealth Program Rheumatology Adult Telehealth Consultations Appointment Scheduling New: 60 minutes We offer telehealth consultations for a variety of adult rheumatology conditions. If you would like to refer a patient for a condition that is Follow-up: 30 minutes not listed, please send your request along with the patient’s chart Level of Presenter notes to the telehealth coordinator for the specialist’s consideration. Required at Consultation Clinical Conditions* M.D., N.P., P. A . • Ankylosing Spondylitis • Antiphospholipid Syndrome New: Option to introduce, • Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition (CPPD) requires 10 minutes at • Carpal Tunnel Syndrome • Dermatomyositis and Polymyositis end of visit and available for exam if needed • Giant Cell Arteritis • Gout • Granulomatosis with Polyangitis (Wegener’s) Follow-up: Requires five minutes at end of the visit • Inflammatory Myopathies • Lupus • Lyme Disease • Osteoarthritis Required Equipment • Osteonecrosis of Hip • Paget’s Disease of Bone • Videoconferencing Unit • Polymyalgia Rheumatica • Psoriatic Arthritis • Raynaud’s Phenomenon • Reactive Arthritis • Rheumatoid Arthritis • Scleroderma Consultants • Sjogren’s Syndrome • Spondyloarthritis Nancy E. Lane, M.D. • Takayasu’s Arteritis • Tendonitis and Bursitis Barton L. Wise, M.D., • Vasculitis MSc, FACP *Please check with the Clinical Telehealth Program for any conditions not listed to see if it is appropriate for telehealth. Information Needed Prior to Scheduling an Appointment • Telehealth Referral Request Form UC Davis Health Clinical Telehealth Program • Pertinent patient records, labs and imaging studies Toll Free Phone: Information Needed Before the Consultation Begins (877) 430-5332 • Signed UC Davis Health Acknowledgement of Receipt: Notice of Referral Fax: Privacy Practices form (new patients only) (866) 622-5944 • Documented verbal consent from the patient for participation in a [email protected] telehealth consultation health.ucdavis.edu/cht. -

Atypical Clinical Manifestations of Acute Poststreptococcal Glomerulonephritis

10 Atypical Clinical Manifestations of Acute Poststreptococcal Glomerulonephritis Toru Watanabe Department of Pediatrics, Niigata City General Hospital Japan 1. Introduction Acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN) is one of the most common and important renal diseases resulting from a prior infection with group A β-hemolytic streptococcus (GAS) (Ash and Ingulli, 2008). Typical clinical features of the disease include an acute onset with gross hematuria, edema, hypertension and moderate proteinuria (acute nephritic syndrome) 1 to 2 weeks after an antecedent streptococcal pharyngitis or 3 to 6 weeks after a streptococcal pyoderma (Ahn & Ingulli 2008; Rodriguez-Iturbe & Mezzano, 2009). Gross hematuria usually disappears after a few days, while edema and hypertension subside in 5 to 10 days (Rodriguez-Iturbe & Mezzano, 2009). Although the incidence of APSGN appears to be decreasing in industrialized countries, more than 472,000 cases with APSGN are estimated to occur each year worldwide, with 97% of them occurring in developing countries (Carapetis et al., 2005; Eison et al., 2010). APSGN occurs most commonly in children, 5 to 12 years old (Ahn & Ingulli, 2008), although 5 to 10 percent of the patients are more than 40 years old (Yoshizawa, 2000). The immediate and long-term prognoses of APSGN are excellent for children, assuming it is diagnosed in a timely fashion (Kasahara et al., 2001, Rodriguez-Iturbe & Musser, 2008). In contrast, adult patients with APSGN show markedly worse prognoses both in the acute phase and in the long-term (Rodriguez-Iturbe & Musser, 2008). The most popular theory of the pathogenic mechanism of APSGN has been the immune- complex theory, which involves the glomerular deposition of nephritogenic streptococcal antigen and subsequent formation of immune complexes in situ and/or the deposition of circulating antigen-antibody complexes (Oda et al., 2010). -

Approach to the Patient with Arthritis Articular Vs

Approach to the Patient with Arthritis Articular Vs. Periarticular Clinical feature Articular Periarticular Anatomic Synovium, Tendon, bursa, structure cartilage, ligament, capsule muscle, bone Painful site Diffuse, deep Focal “point” Pain on Active/passive, Active, in few movement all planes planes Swelling Common Uncommon Inflammatory versus Noninflammatory Arthritis Inflammatory Arthritis Noninflammatory Arthritis • Pain and stiffness typically are • Pain that worsens with worse in the morning or after periods of inactivity (the so- activity and improves with called "gel phenomenon") and rest. Stiffness is generally improve with mild to mild moderate activity. • Elevated erythrocyte • The ESR and CRP are usually sedimentation rate (ESR) and a normal. high C-reactive protein (CRP) level • The synovial fluid WBC • The synovial fluid WBC count count is is <2000/mm3 in is >2000/mm3 in inflammatory noninflammatory arthritis arthritis. Constitutional Symptoms Active infection Not due to active infection 1. Septic arthritis 1. Systemic lupus erythematosus 2. Disseminated gonococcal 2. Drug-induced lupus infection 3. Still disease 4. Gout/ Pseudogout 3. Endocarditis 5. Reactive arthritis (particularly in 4. Acute viral infections its early phases) 6. Acute rheumatic fever and 5. Mycobacterial poststreptococcal arthritis 6. Fungal 7. Inflammatory bowel disease 8. Acute sarcoidosis 9. Systemic vasculitis 10. Familial Mediterranean fever and other inherited periodic fever syndromes 11. Paraneoplastic arthritis Skin Lesions Useful in Diagnosis -

Reactive Arthritis Or Chronic Infectious Arthritis? J Sibilia, F-X Limbach

580 REVIEW Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.61.7.580 on 1 July 2002. Downloaded from Reactive arthritis or chronic infectious arthritis? J Sibilia, F-X Limbach ............................................................................................................................. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:580–587 Microbes reach the synovial cavity either directly during hence active multiplication of the bacteria. bacteraemia or by transport within lymphoid cells or These findings thus suggest that microbes can survive in small numbers in the articular cavity monocytes. This may stimulate the immune system in certain forms of ReA (table 1). excessively, triggering arthritis. Some forms of ReA • The phenomenon has grown since 1995 with correspond to slow infectious arthritis due to the discovery of DNA of most other classical persistence of microbes and some to an infection arthritogenic agents in synovial samples from patients with ReA.18–21 One must nevertheless triggered arthritis linked to an extra-articular site of take a fairly critical point of view because infection. although the results are convincing for C .......................................................................... trachomatis, they are much less so for entero- bacteria. It is true that DNA of Yersinia, Shigella, or Campylobacter has been identified in some eactive arthritis (ReA) was first described in studies, but these are few and include very few 1916 during the first world war by Fiessinger patients.18 19 21 22 Thus, Ekman et al identified and Leroy in France and Reiter in Germany. R DNA of Salmonella in synovial samples,23 but It was, however, only in 1969 that a Scandinavian could not repeat their results. This might have team rationalised the concept of ReA by defining it as a transient non-purulent (reactive) arthritis been owing to technical artefacts, which lead appearing in the weeks following a digestive to false positives, or to a very small amount of infection.1 Actually, this notion of exclusively bacterial DNA in the synovium. -

British Medical Association Tavistock Square London WC1H 9JR

Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases August 1989 Vol. 48 No. 8 Ann Rheum Dis: first published as on 1 August 1989. Downloaded from Contents Page Journal summary 617 Leader 'Chondroprotection' by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs MICHAEL DOHERTY 619 Notes and news 622 Scientific papers Effect of ind6methacin on swelling, lymphocyte influx, and cartilage proteoglycan depletion in experimental arthritis ER PETrIPHER, B HENDERSON, J C W EDWARDS, AND G A HIGGS 623 Pathogenesis of square bodies in ankylosing spondylitis M AUFDERMAUR 628 Pulmonary function and maximal transrespiratory pressures in ankylosing spondylitis D VANDERSCHUEREN, M DECRAMER, P VAN DEN DAELE, AND J DEQUEKER 632 Correlation between synovial neopterin and inflammatory activity in rheumatoid arthritis ANDRES KRAUSE, HUBERTUS PROTZ, AND KLAUS M GOEBEL 636 Urinary excretion of the hydroxypyridinium cross links of collagen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis D BLACK, M MARABANI, R D STURROCK, AND S P ROBINS 641 Immunolocalisation of matrix metalloproteinase 3 (stromelysin) in rheumatoid synovioblasts (B cells): correlation with rheumatoid arthritis YASUNORI OKADA, NAOTO TAKEUCHI, KATSURO TOMITA, et al 645 Serum osteocalcin concentrations in patients with rheumatoid arthritis P PIETSCHMANN, K P MACHOLD, W WOLOSCZUK, AND J S SMOLEN 654 Treatment of polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis. I. Steroid regimens in the first two http://ard.bmj.com/ months v KYLE AND BL HAZLEMAN 658 Treatment of polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis. II. Relation between steroid dose and steroid associated side effects v KYLE AND B L HAZLEMAN 662 Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein in the assessment of polymyalgia rheumatica/giant cell arteritis on presentation and during follow up VALERIE KYLE, TIM E CAWSTON, AND BRIAN L HAZLEMAN 667 on September 23, 2021 by guest.