Brain Indices of Music Processing: ``Nonmusicians'' Are Musical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Modulation —

— On Modulation — Dean W. Billmeyer University of Minnesota American Guild of Organists National Convention June 25, 2008 Some Definitions • “…modulating [is] going smoothly from one key to another….”1 • “Modulation is the process by which a change of tonality is made in a smooth and convincing way.”2 • “In tonal music, a firmly established change of key, as opposed to a passing reference to another key, known as a ‘tonicization’. The scale or pitch collection and characteristic harmonic progressions of the new key must be present, and there will usually be at least one cadence to the new tonic.”3 Some Considerations • “Smoothness” is not necessarily a requirement for a successful modulation, as much tonal literature will illustrate. A “convincing way” is a better criterion to consider. • A clear establishment of the new key is important, and usually a duration to the modulation of some length is required for this. • Understanding a modulation depends on the aural perception of the listener; hence, some ambiguity is inherent in distinguishing among a mere tonicization, a “false” modulation, and a modulation. • A modulation to a “foreign” key may be easier to accomplish than one to a diatonically related key: the ear is forced to interpret a new key quickly when there is a large change in the number of accidentals (i.e., the set of pitch classes) in the keys used. 1 Max Miller, “A First Step in Keyboard Modulation”, The American Organist, October 1982. 2 Charles S. Brown, CAGO Study Guide, 1981. 3 Janna Saslaw: “Modulation”, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 5 May 2008), http://www.grovemusic.com. -

Eduqas-Bach-Badinerie-Musical-Analysis.Pdf

Musical Analysis Bach: Badinerie J.S.Bach: BADINERIE from Orchestral Suite No.2 Melodic Analysis The entire movement is based on two musical motifs: X and Y. Section A Bars 02 – 161 Sixteen bars Bars 02 – 21 The movement opens with the first statement of motif X, which is played by the flute. The motif is a descending B minor arpeggio/broken chord with a characteristic quaver and semiquaver(s) rhythm. Bars 22 – 41 The melodic material remains with the flute for the first statement of motif Y. This motifis an ascending semiquaver figure consisting of both arpeggios/broken chords sand conjunct movement. Bars 42 – 61 Motif X is then restated by the flute. Music | Bach: Badinerie - Musical Analysis 1 Musical Analysis Bach: Badinerie Bars 62 – 81 Motif X is presented by the cellos in a slightly modified version in which the last crotchet of the motif is replaced with a quaver and two semiquavers. This motif moves the tonality to A major and is also the initial phrase in a musical sequence. Bars 82 – 101 Motif X remains with the cellos with a further modified ending in which the last crotchet is replaced with four semiquavers. It moves the tonality to the dominant minor, F# minor, and is the answering phrase in a musical sequence that began in bar 62. Bars 102 – 121 Motif Y returns in the flute part with a modified ending in which the last two quavers are replaced by four semiquavers. Bars 122 – 161 The flute continues to present the main melodic material. Motif Y is both extended and developed, and Section A is brought to a close in F# minor. -

Viewed by Most to Be the Act of Composing Music As It Is Being

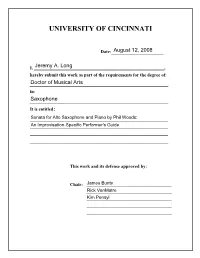

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods: An Improvisation-Specific Performer’s Guide A doctoral document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music By JEREMY LONG August, 2008 B.M., University of Kentucky, 1999 M.M., University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, 2002 Committee Chair: Mr. James Bunte Copyright © 2008 by Jeremy Long All rights reserved ABSTRACT Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods combines Western classical and jazz traditions, including improvisation. A crossover work in this style creates unique challenges for the performer because it requires the person to have experience in both performance practices. The research on musical works in this style is limited. Furthermore, the research on the sections of improvisation found in this sonata is limited to general performance considerations. In my own study of this work, and due to the performance problems commonly associated with the improvisation sections, I found that there is a need for a more detailed analysis focusing on how to practice, develop, and perform the improvised solos in this sonata. This document, therefore, is a performer’s guide to the sections of improvisation found in the 1997 revised edition of Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods. -

Evaluating Prolongation in Extended Tonality

Evaluating Prolongation in Extended Tonality <http://mod7.shorturl.com/prolongation.htm> Robert T. Kelley Florida State University In this paper I shall offer strategies for deciding what is structural in extended-tonal music and provide new theoretical qualifications that allow for a conservative evaluation of prolongational analyses. Straus (1987) provides several criteria for finding post-tonal prolongation, but these can simply be reduced down to one important consideration: Non-tertian music clouds the distinction between harmonic and melodic intervals. Because linear analysis depends upon this distinction, any expansion of the prolongational approach for non-tertian music must find alternative means for defining the ways in which transient tones elaborate upon structural chord tones to foster a sense of prolongation. The theoretical work that Straus criticizes (Salzer 1952, Travis 1959, 1966, 1970, Morgan 1976, et al.) fails to provide a method for discriminating structural tones from transient tones. More recently, Santa (1999) has provided associational models for hierarchical analysis of some post-tonal music. Further, Santa has devised systems for determining salience as a basis for the assertion of structural chords and melodic pitches in a hierarchical analysis. While a true prolongational perspective cannot be extended to address most post-tonal music, it may be possible to salvage a prolongational approach in a restricted body of post-tonal music that retains some features of tonality, such as harmonic function, parsimonious voice leading, or an underlying diatonic collection. Taking into consideration Straus’s theoretical proviso, we can build a model for prolongational analysis of non-tertian music by establishing how non-tertian chords may attain the status of structural harmonies. -

In Search of the Perfect Musical Scale

In Search of the Perfect Musical Scale J. N. Hooker Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, USA [email protected] May 2017 Abstract We analyze results of a search for alternative musical scales that share the main advantages of classical scales: pitch frequencies that bear simple ratios to each other, and multiple keys based on an un- derlying chromatic scale with tempered tuning. The search is based on combinatorics and a constraint programming model that assigns frequency ratios to intervals. We find that certain 11-note scales on a 19-note chromatic stand out as superior to all others. These scales enjoy harmonic and structural possibilities that go significantly beyond what is available in classical scales and therefore provide a possible medium for innovative musical composition. 1 Introduction The classical major and minor scales of Western music have two attractive characteristics: pitch frequencies that bear simple ratios to each other, and multiple keys based on an underlying chromatic scale with tempered tuning. Simple ratios allow for rich and intelligible harmonies, while multiple keys greatly expand possibilities for complex musical structure. While these tra- ditional scales have provided the basis for a fabulous outpouring of musical creativity over several centuries, one might ask whether they provide the natural or inevitable framework for music. Perhaps there are alternative scales with the same favorable characteristics|simple ratios and multiple keys|that could unleash even greater creativity. This paper summarizes the results of a recent study [8] that undertook a systematic search for musically appealing alternative scales. The search 1 restricts itself to diatonic scales, whose adjacent notes are separated by a whole tone or semitone. -

Transfer Theory Placement Exam Guide (Pdf)

2016-17 GRADUATE/ transfer THEORY PLACEMENT EXAM guide! Texas woman’s university ! ! 1 2016-17 GRADUATE/transferTHEORY PLACEMENTEXAMguide This! guide is meant to help graduate and transfer students prepare for the Graduate/ Transfer Theory Placement Exam. This evaluation is meant to ensure that students have competence in basic tonal harmony. There are two parts to the exam: written and aural. Part One: Written Part Two: Aural ‣ Four voice part-writing to a ‣ Melodic dictation of a given figured bass diatonic melody ‣ Harmonic analysis using ‣ Harmonic Dictation of a Roman numerals diatonic progression, ‣ Transpose a notated notating the soprano, bass, passage to a new key and Roman numerals ‣ Harmonization of a simple ‣ Sightsinging of a melody diatonic melody that contains some functional chromaticism ! Students must achieve a 75% on both the aural and written components of the exam. If a passing score is not received on one or both sections of the exam, the student may be !required to take remedial coursework. Recommended review materials include most of the commonly used undergraduate music theory texts such as: Tonal Harmony by Koska, Payne, and Almén, The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis by Clendinning and Marvin, and Harmony in Context by Francoli. The exam is given prior to the beginning of both the Fall and Spring Semesters. Please check the TWU MUSIc website (www.twu.edu/music) ! for the exact date and time. ! For further information, contact: Dr. Paul Thomas Assistant Professor of Music Theory and Composition [email protected] 2 2016-17 ! ! ! ! table of Contents ! ! ! ! ! 04 Part-Writing ! ! ! ! ! 08 melody harmonization ! ! ! ! ! 13 transposition ! ! ! ! ! 17 Analysis ! ! ! ! ! 21 melodic dictation ! ! ! ! ! harmonic dictation ! 24 ! ! ! ! Sightsinging examples ! 28 ! ! ! 31 terms ! ! ! ! ! 32 online resources ! 3 PART-Writing Part-writing !Realize the following figured bass in four voices. -

Diatonic Harmony

Music Theory for Musicians and Normal People Diatonic Harmony tobyrush.com music theory for musicians and normal people by toby w. rush although a chord is technically any combination of notes Triads played simultaneously, in music theory we usually define chords as the combination of three or more notes. secundal tertial quartal quintal harmony harmony harmony harmony and œ harmony? œœ œ œ œ œœ œ œ tertial œ œ œ septal chords built from chords built from chords built from chords built from seconds form thirds (MORE perfect fourths perfect fifths tone clusters, SPECifically, from create a different can be respelled as respectively. harmony, which are not major thirds and sound, used in quartal chords, harmonic so much minor thirds) compositions from and as such they harmony? as timbral. form the basis of the early 1900s do not create a most harmony in and onward. separate system of are the same as as with quintal harmony, these harmony, as with quintal the common harmony. secundal practice period. sextal well, diminished thirds sound is the chord still tertial just like major seconds, and if it is built from diminished augmented thirds sound just thirds or augmented thirds? like perfect fourths, so... no. œ œ the lowest note in the chord & œ let’s get started when the chord is in simple on tertial harmony form is called œ the the & œ with the smallest root. fifth œ chord possible: names of the œ third ? œ when we stack the triad. other notes œ the chord in are based on root thirds within one octave, their interval we get what is called the above the root. -

MUS 211/211L Advanced Music Theory II and Lab MUS 313 Form and Analysis MUS 420

South Dakota State University MUS 211/211L Advanced Music Theory II and Lab MUS 313 Form and Analysis MUS 420 Concept: Music Theory "Compositional organization, such as pitch, including scale types and harmony; rhythm; texture; form; expressive elements, such as dynamics, articulation, tempo, and timbre; and basic aural skills: intervals, chords, scales, rhythms, melodies" MUS 211/211 L: Advanced Music Theory II and Lab (Note: since the skills and information regarding basic undergraduate music theory are taught in a "spiraling" manner through MUS 110, 111, 210, and 211, and MUS 211 is considered to be the course in which these materials are presented at a level commensurate with the level of the material as it appears on the Praxis test, this study guide reviews compositional organization as it was taught throughout the entire two-year theory sequence, and refers to pages in both the fall semester [MUS 210] and spring semester [MUS 211] class packets you purchased during the sophomore theory year.) Compositional Organization Students should refer to: The specific pages listed below from the class packets mentioned above, as well as Joe Dineen and Mark Bridge's Gig Bag Book of Theory and Harmony and Robert Ottman's Music for Sight Singing, 6th ed. (Note: the material and the page numbers in your class packets may vary slightly from what is listed below, depending on which year you took the course.) Specifically, students should review: From the fall semester of Sophomore Theory (MUS 210): o Rudiments (notation, scales/key, intervals, -

Augmented Sixth Chords Are Predominant Chords, Meaning They Are Used to Approach Dominant Chords

Augmentedmusic Sixth theory for musicians Chords and normal people by toby w. rush like that moment of incredible tension just before the hero finally kisses the leading lady, the half-step is the go-to interval for creating tension in music of the common ˙ practice period. it drives the entire style! ˙ if one half-step can create such strong tension, how about two half-steps sounding simultaneously? Let’s get creative here for a minute to find a cool new way to approach a diatonic chord. in this case, we’ll use them to approach the dominant triad. ...and approach that first, we’ll start with octave with a half step the doubled root of a below the top note, V chord... #˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ & b ˙ ˙ & b ˙ ˙ V & ˙ V ...and, finally, add the V ...and a half step above tonic as the third note. the bottom note... the result is a new chord, one we call the augmented sixth chord, after the interval created by the top and bottom notes. augmented sixth chords are predominant chords, meaning they are used to approach dominant chords. if we just use they are usually used to approach dominant triads, three notes not dominant sevenths, because of the doubled and double the roots present in dominant triads. tonic, we get the #w italian ww however, they also often augmented sixth. b w & approach tonic chords & #˙ ˙ It.6 in second inversion, ˙ ˙ which also contain a doubled fifth scale degree. ? b˙ n˙ b ˙ ˙ if we add the 6 Ger.6 I4 second scale degree instead ˙ ˙ rarely, augmented sixth chords of doubling the # w & ˙ ˙ are found transposed down tonic, we get the ww a perfect fifth, analyzed as french b w ˙ ˙ “on flat two,” and used to augmented sixth. -

The Augmented Sixth Chord

CHAPTER24 The Augmented Sixth Chord Characteristics, Derivation, and Behavior The two excerpts in Example 24.1 are from different style periods, yet they share several features. In terms of form and harmony, both divide into two subphrases and close with strong half cadences. Further, the pre-dominant harmony in both examples is the same: an altered iv6 chord. Indeed, we hear not a Phrygian cadence (iv6-V), but rather some chromatic version, where the diatonic major sixth above the bass is raised a half step to create the strongly directed interval of the augmented sixth (+6). The new half-step ascent (#4-5) mirrors the bass's half-step descent (6-5). We refer to such chromatic pre-dominants as augmented sixth chords because of the characteristic interval between the bass 6 and the upper-voice #4. Listen to both excerpts in Example 24.1, noting the striking sound of the augmented sixth chords. EXAMPLE 24.1 A. Schubert, WaltzinG minor, Die letzte Walzer, op. 127, no. 12, D. 146 472 CHAPTER 24 THE AUGMENTED SIXTH CHORD 473 B. Handel, "Since by Man Came Death," Messiah, HWV 56 Example 24.2 demonstrates the derivation of the augmented sixth chord from the Phrygian cadence. Example 24.2A represents a traditional Phrygian half cadence. In Example 24.2B, the chromatic F# fills the space between F and G, and the passing motion creates an interval of an augmented sixth. Finally, Example 24.2C shows the augmented sixth chord as a harmonic entity, with no consonant preparation. EXAMPLE 24.2 Phrygian Cadence Generates the Augmented Sixth Chord Given that the augmented sixth chord also occurs in major, one might ask if it is an example of an applied chord or a mixture chord? To answer this question, consider the diatonic progression in Example 24.3A. -

Rock Harmony Reconsidered: Tonal, Modal and Contrapuntal Voice&

DOI: 10.1111/musa.12085 BRAD OSBORN ROCK HARMONY RECONSIDERED:TONAL,MODAL AND CONTRAPUNTAL VOICE-LEADING SYSTEMS IN RADIOHEAD A great deal of the harmony and voice leading in the British rock group Radiohead’s recorded output between 1997 and 2011 can be heard as elaborating either traditional tonal structures or establishing pitch centricity through purely contrapuntal means.1 A theory that highlights these tonal and contrapuntal elements departs from a number of developed approaches in rock scholarship: first, theories that focus on fretboard-ergonomic melodic gestures such as axe- fall and box patterns;2 second, a proclivity towards analysing chord roots rather than melody and voice leading;3 and third, a methodology that at least tacitly conflates the ideas of hypermetric emphasis and pitch centre. Despite being initially yoked to the musical conventions of punk and grunge (and their attendant guitar-centric compositional practice), Radiohead’s 1997– 2011 corpus features few of the characteristic fretboard gestures associated with rock harmony (partly because so much of this music is composed at the keyboard) and thus demands reconsideration on its own terms. This mature period represents the fullest expression of Radiohead’s unique harmonic, formal, timbral and rhythmic idiolect,4 as well as its evolved instrumentation, centring on keyboard and electronics. The point here is not to isolate Radiohead’s harmonic practice as something fundamentally different from all rock which came before it. Rather, by depending less on rock-paradigmatic gestures such as pentatonic box patterns on the fretboard, their music invites us to consider how such practices align with existing theories of rock harmony while diverging from others. -

10Th Grade Music – Choir I: Harmonic Function May 11 – May 15 Time Allotment: 20 Minutes Per Day

10th Grade Music – Choir I: Harmonic Function May 11 – May 15 Time Allotment: 20 minutes per day Student Name: ________________________________ Teacher Name: ________________________________ Academic Honesty I certify that I completed this assignment I certify that my student completed this independently in accordance with the GHNO assignment independently in accordance with Academy Honor Code. the GHNO Academy Honor Code. Student signature: Parent signature: ___________________________ ___________________________ Music – Choir I: Harmonic Function May 11 – May 15 Packet Overview Date Objective(s) Page Number Monday, May 11 1. Review Roman numeral identification of chords 2 2. Introduce chord voicing (expanded form) Tuesday, May 12 1. Introduce harmonic function and chord 6 substitution Wednesday, May 13 1. Decode tonic/dominant relationship and define 9 goal of motion within the context of analysis Thursday, May 14 1. Discern predominant function within chorale 12 analysis Friday, May 15 1. Demonstrate understanding of harmonic function 13 by taking a written assessment. Additional Notes: In order to complete the tasks within the following packet, it would be helpful for students to have a piece of manuscript paper to write out triads; I have included a blank sheet of manuscript paper to be printed off as needed, though in the event that this is not feasible students are free to use lined paper to hand draw a music staff. I have also included answer keys to the exercises at the end of the packet. Parents, please facilitate the proper use of these answer documents (i.e. have students work through the exercises for each day before supplying the answers so that they can self-check for comprehension.) As always, will be available to provide support via email, and I will be checking my inbox regularly.