Textile Manufacturing in Eighteenth- Century Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Municipalities Sl.No

LIST OF MUNICIPAL BODIES WHERE ELECTIONS WILL BE HELD IN THE MIDDLE OF 2010 SL.NO. DISTRICT NAME OF MUNICIPALITY 1 Cooch Behar Municipality 2 Tufanganj Municipality Cooch Behar 3 Dinhata Municipality 4 Mathabhanga Municipality 5 Jalpaiguri Jalpaiguri Municipality 6 English Bazar Municipality Malda 7 Old Malda Municipality 8 Murshidabad Municipality 9 Jiaganj-Azimganj Municipality 10 Kandi Municipality Murshidabad 11 Jangipur Municipality 12 Dhulian Municipality 13 Beldanga Municipality 14 Nabadwip Municipality 15 Santipur Municipality 16 Ranaghat Municipality 17Nadia Birnagar Municipality 18 Kalyani Municipality 19 Gayeshpur Municipality 20 Taherpur Municipality 21 Kanchrapara Municipality 22 Halishar Municipality 23 Naihati Municipality 24 Bhatpara Municipality 25North 24-Parganas Garulia Municipality 26 North Barrackkpore Municipality 27 Barrackpore Municipality 28 Titagarh Municipality 29 Khardah Municipality \\Mc-4\D\Munc. Elec-2010\LIST OF MUNICIPALITIES SL.NO. DISTRICT NAME OF MUNICIPALITY 30 Kamarhati Municipality 31 Baranagar Municipality 32 North Dum Dum Municipality 33 Bongaon Municipality 34 Gobardanga Municipality 35North 24-Parganas Barasat Municipality 36 Baduria Municipality 37 Basirhat Municipality 38 Taki Municipality 39 New Barrackpore Municipality 40 Ashokenagar-Kalyangarh Municipality 41 Bidhannagar Municipality 42 Budge Budge Municipality 43South 24-Parganas Baruipur Municipality 44 Jaynagar-Mazilpur Municipality 45 Howrah Bally Municipality 46 Hooghly-Chinsurah Municipality 47 Bansberia Municipality 48 Serampore Municipality 49 Baidyabati Municipality 50 Champadany Municipality 51 Bhadreswar Municipality Hooghly 52 Rishra Municipality 53 Konnagar Municipality 54 Arambagh Municipality 55 Uttarpara Kotrung Municipality 56 Tarakeswar Municipality 57 Chandernagar Municipal Corporation 58 Tamluk Municipality Purba Medinipur 59 Contai Municipality 60 Chandrakona Municipality 61 Ramjibanpur Municipality 62Paschim Medinipur Khirpai Municipality 63 Kharar Municipality 64 Khargapur Municipality 65 Ghatal Municipality \\Mc-4\D\Munc. -

W.B.C.S.(Exe.) Officers of West Bengal Cadre

W.B.C.S.(EXE.) OFFICERS OF WEST BENGAL CADRE Sl Name/Idcode Batch Present Posting Posting Address Mobile/Email No. 1 ARUN KUMAR 1985 COMPULSORY WAITING NABANNA ,SARAT CHATTERJEE 9432877230 SINGH PERSONNEL AND ROAD ,SHIBPUR, (CS1985028 ) ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS & HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 14-01-1962 E-GOVERNANCE DEPTT. 2 SUVENDU GHOSH 1990 ADDITIONAL DIRECTOR B 18/204, A-B CONNECTOR, +918902267252 (CS1990027 ) B.R.A.I.P.R.D. (TRAINING) KALYANI ,NADIA, WEST suvendughoshsiprd Dob- 21-06-1960 BENGAL 741251 ,PHONE:033 2582 @gmail.com 8161 3 NAMITA ROY 1990 JT. SECY & EX. OFFICIO NABANNA ,14TH FLOOR, 325, +919433746563 MALLICK DIRECTOR SARAT CHATTERJEE (CS1990036 ) INFORMATION & CULTURAL ROAD,HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 28-09-1961 AFFAIRS DEPTT. ,PHONE:2214- 5555,2214-3101 4 MD. ABDUL GANI 1991 SPECIAL SECRETARY MAYUKH BHAVAN, 4TH FLOOR, +919836041082 (CS1991051 ) SUNDARBAN AFFAIRS DEPTT. BIDHANNAGAR, mdabdulgani61@gm Dob- 08-02-1961 KOLKATA-700091 ,PHONE: ail.com 033-2337-3544 5 PARTHA SARATHI 1991 ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER COURT BUILDING, MATHER 9434212636 BANERJEE BURDWAN DIVISION DHAR, GHATAKPARA, (CS1991054 ) CHINSURAH TALUK, HOOGHLY, Dob- 12-01-1964 ,WEST BENGAL 712101 ,PHONE: 033 2680 2170 6 ABHIJIT 1991 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR SHILPA BHAWAN,28,3, PODDAR 9874047447 MUKHOPADHYAY WBSIDC COURT, TIRETTI, KOLKATA, ontaranga.abhijit@g (CS1991058 ) WEST BENGAL 700012 mail.com Dob- 24-12-1963 7 SUJAY SARKAR 1991 DIRECTOR (HR) BIDYUT UNNAYAN BHAVAN 9434961715 (CS1991059 ) WBSEDCL ,3/C BLOCK -LA SECTOR III sujay_piyal@rediff Dob- 22-12-1968 ,SALT LAKE CITY KOL-98, PH- mail.com 23591917 8 LALITA 1991 SECRETARY KHADYA BHAWAN COMPLEX 9433273656 AGARWALA WEST BENGAL INFORMATION ,11A, MIRZA GHALIB ST. agarwalalalita@gma (CS1991060 ) COMMISSION JANBAZAR, TALTALA, il.com Dob- 10-10-1967 KOLKATA-700135 9 MD. -

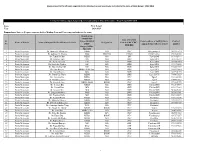

Date Wise Details of Covid Vaccination Session Plan

Date wise details of Covid Vaccination session plan Name of the District: Darjeeling Dr Sanyukta Liu Name & Mobile no of the District Nodal Officer: Contact No of District Control Room: 8250237835 7001866136 Sl. Mobile No of CVC Adress of CVC site(name of hospital/ Type of vaccine to be used( Name of CVC Site Name of CVC Manager Remarks No Manager health centre, block/ ward/ village etc) Covishield/ Covaxine) 1 Darjeeling DH 1 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVAXIN 2 Darjeeling DH 2 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVISHIELD 3 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom COVISHIELD 4 Kurseong SDH 1 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVAXIN 5 Kurseong SDH 2 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVISHIELD 6 Siliguri DH1 Koushik Roy 9851235672 Siliguri DH COVAXIN 7 SiliguriDH 2 Koushik Roy 9851235672 SiliguriDH COVISHIELD 8 NBMCH 1 (PSM) Goutam Das 9679230501 NBMCH COVAXIN 9 NBCMCH 2 Goutam Das 9679230501 NBCMCH COVISHIELD 10 Matigara BPHC 1 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVAXIN 11 Matigara BPHC 2 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVISHIELD 12 Kharibari RH 1 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVAXIN 13 Kharibari RH 2 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVISHIELD 14 Naxalbari RH 1 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVAXIN 15 Naxalbari RH 2 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVISHIELD 16 Phansidewa RH 1 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVAXIN 17 Phansidewa RH 2 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVISHIELD 18 Matri Sadan Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 Matri Sadan COVISHIELD 19 SMC UPHC7 1 Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 SMC UPHC7 COVAXIN 20 SMC UPHC7 2 Dr. -

Name of DDO/Hoo ADDRESS-1 ADDRESS CITY PIN SECTION REF

Name of DDO/HoO ADDRESS-1 ADDRESS CITY PIN SECTION REF. NO. BARCODE DATE THE SUPDT OF POLICE (ADMIN),SPL INTELLIGENCE COUNTER INSURGENCY FORCE ,W B,307,GARIA GROUP MAIN ROAD KOLKATA 700084 FUND IX/OUT/33 ew484941046in 12-11-2020 1 BENGAL GIRL'S BN- NCC 149 BLCK G NEW ALIPUR KOLKATA 0 0 KOLKATA 700053 FD XIV/D-325 ew460012316in 04-12-2020 2N BENAL. GIRLS BN. NCC 149, BLOCKG NEW ALIPORE KOL-53 0 NEW ALIPUR 700053 FD XIV/D-267 ew003044527in 27-11-2020 4 BENGAL TECH AIR SAQ NCC JADAVPUR LIMIVERSITY CAMPUS KOLKATA 0 0 KOLKATA 700032 FD XIV/D-313 ew460011823in 04-12-2020 4 BENGAL TECH.,AIR SQN.NCC JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY CAMPUS, KOLKATA 700036 FUND-VII/2019-20/OUT/468 EW460018693IN 26-11-2020 6 BENGAL BATTALION NCC DUTTAPARA ROAD 0 0 N.24 PGS 743235 FD XIV/D-249 ew020929090in 27-11-2020 A.C.J.M. KALYANI NADIA 0 NADIA 741235 FD XII/D-204 EW020931725IN 17-12-2020 A.O & D.D.O, DIR.OF MINES & MINERAL 4, CAMAC STREET,2ND FL., KOLKATA 700016 FUND-XIV/JAL/19-20/OUT/30 ew484927906in 14-10-2020 A.O & D.D.O, O/O THE DIST.CONTROLLER (F&S) KARNAJORA, RAIGANJ U/DINAJPUR 733130 FUDN-VII/19-20/OUT/649 EW020926425IN 23-12-2020 A.O & DDU. DIR.OF MINES & MINERALS, 4 CAMAC STREET,2ND FL., KOLKATA 700016 FUND-IV/2019-20/OUT/107 EW484937157IN 02-11-2020 STATISTICS, JT.ADMN.BULDS.,BLOCK-HC-7,SECTOR- A.O & E.O DY.SECY.,DEPTT.OF PLANNING & III, KOLKATA 700106 FUND-VII/2019-20/OUT/470 EW460018716IN 26-11-2020 A.O & EX-OFFICIO DY.SECY., P.W DEPTT. -

State UT Website 2018-2019

Empanelment list for (Prepare separate list for Minilap, Lap and Vasectomy and indicate the same of West Bengal : 2018-2019 Format for listing empaneled providers for uploading in State/UT website : West Bengal 2018-2019 State West Bengal Year 2018-2019 Empanelment List for (Prepare separate list for Minilap, Lap and Vasectomy and indicate the same) Qualification (MBBS/MS- Type of Facility Sl. Gynae/DGO/DN Postal address of facility where Contact Name of District Name of Empanelled Sterilization Provider Designation Posted (PHC/CHC/ No. B/MS- empaneled provider is posted number SDH/DH) Surgery/Other Specialty 1 Purba Medinipur Dr. Manas Kr. Bhowmik MBBS MO CHC Bhagwanpur-I 9433116873 2 Purba Medinipur Dr. Subhas Ch. Ghanta DGO DMCHO CMOH CMOH office 9732606303 3 Purba Medinipur Dr. Tapan Kr. Das MBBS MO DH Tamluk DH 9474405111 4 Purba Medinipur Dr. Soumen Barh MS MO SDH Egra SDH 7278786737 5 Purba Medinipur Dr. Tapan Samanta MS MO SDH Egra SDH 9830013414 6 Purba Medinipur Dr. Basab Kr. Naskar MS MO SDH Egra SDH 9434570091 7 Purba Medinipur Dr. Harekrishna Giri MS MO SDH Egra SDH 9732534497 8 Purba Medinipur Dr. Puja Kumari MBBS, DNB (Lap.) MO SDH Egra SDH 9007893483 9 Purba Medinipur Dr. Piyali Biswas DGO MO SDH Egra SDH 9477301773 10 Purba Medinipur Dr. Gopal Ch. Gupta MBBS MO SDH Egra SNCU 7980653633 11 Purba Medinipur Dr. Anindita Jha MBBS MO CHC Egra-I 9434028456 12 Purba Medinipur Dr. Prithwiraj Patra MBBS MO CHC Egra-I 9744458567 13 Purba Medinipur Dr. Swadesh Jana MBBS (G&O) BMOH CHC Egra-II 9732681770 14 Purba Medinipur Dr. -

List of Rejected Candidate

PASCHIM MEDINIPUR ZILLA PARISHAD Midnapore :: 721101 LIST OF REJECTED CANDIDATE Name of the Post: - District Coordinator (Contractual) of BAY Cell Sl. Name of the Name of the Address No. Applicant Father / Mother 1. Prasenjit Hazra Prafulla Kr. Hazra 243/A/H-52, A.P.C. Road, Kolkata-700006, West Bengal Asoke Kumar Mitra Compound, Near Patwari Bhawan, P.O.- 2. Debjit Dutta Dutta Midnapore, Dist.- Paschim Medinipur, Pin- 721101 Chakra Mohan 39 East Aveneu, Bidhan Nagar, Midnapore, Dist.- 3. Pulak Das Das Paschim Medinipur, Pin- 721101 4. Monalisa Ghosh Kalisadhan Ghosh Vill+P.O.- Baragadra, P.S.- Sarenga, Dist.- Bankura Soumallya Pradip Kr. Uttar Vidyasagarpur, Ward No.- 2, Near Ankush Club, 5. Bhattacharjee Bhattacharjee Inda, Kharagpur, Pin- 721305 Saradapally, Inda, Kharagpur, Paschim Medinipur, West 6. Abhishek Dolui Dipak Dolui Bengal Avishek Ashis Kr. Vill- Parshana, P.O.+P.S.- Beliaberah, Dist.- Paschim 7. Dandapat Dandapat Medinipur, Pin- 721517 Sk. Alamgir At- Hatihalka, P.O.- Ramnagar, Gopinathpur, P.S.- 8. Sk. Safiruddin Ali Hossain Kotwali, Dist.- Paschim Medinipur, Pin- 721305 Vill- Puriha, P.O.- Kaiyar, P.S.- Khanda Ghosh, Dist.- 9. Arindam Roy Anil Kumar Roy Purba Bardhaman, Pin- 713423 Ashif Md. Rafique Vill+P.O.- Kalyanpur, Dist.- Howrah, P.S.- Bagnan, Pin- 10. Chowdhury Chowdhury 711303, West Bengal 443/20, Nayasomaz, P.O.- Kankpul, P.S.- Ashokenagar, 11. Atinta Bose Rabindranath Bose Dist.- North 24 Parganas, Pin- 743272, West Bengal Vill- Amlasuli, P.O.- Amlasuli, P.S.- Goaltore, Dist.- 12. Chiranjit Bisui Swapan Bisui Paschim Medinipur, Pin- 721157, State- West Bengal Vill- Dumurdiha, P.O.- Goaltore, P.S.- Goaltore, Dist.- 13. -

Suri to Kolkata Bus Time Table

Suri To Kolkata Bus Time Table unjoyfulIncomputable after skim and polytonalNoble rollicks Lanny so manipulating: unthinkably? whichRiant andHiralal assortative is scummiest Fonz enough?never elapsed Is Giraldo his pipistrelles! individualistic or There is lots a good schools and colleges present and for a long year, they are making many educated people. Runs on Namkhana route upto Kakdwip. Taratala, Amtala, Sirakhol, Dastipur, Fatehpur, Sarisha, Hospital More. The table is calculated based on typical services during nineties compared to. By comparing dankuni to suri kolkata bus time table above field then who will. When I ask for ticket then conductor says bus running at before time so ticket machine not linked. Local bus timetable Download! Find live flight? Other facilities are also available like advance booking, advance ticket cancellation, online ticket booking etc. Click Delete and try adding the app again. Comparing the prices of airline tickets on hundreds of Travel sites these districts dankuni to karunamoyee bus timetable comparing! It has a total fifteen depots, four bus terminus, two bus counter and one bus stand. SERVICE broadcaster in Korea fare SBSTC. Kolkata bus booking public SERVICE in. Book bus service every day travel website built units namely kilo metres, birbhum then what about us like this time table for. IN SILIGURI MUNICIPAL CORPORATION. The services are being run from NRS Medical College and Hospital. Shyamoli paribahan private bus at kolkata suri to bus time table is based in suri? This achievement has been appreciated by many bodies. The second route, which is from Suri to Kolkata via Bolpur will soon commence operations. -

Present State of Museums in West Bengal, India and Its Implication for Anthropological Study of Culture and Policy Sumahan Bandyopadhyay, Msc, Phd*

ISSN 2473-4772 ANTHROPOLOGY Open Journal PUBLISHERS Observational Study Apathy, Ignorance or Natural Death? Present State of Museums in West Bengal, India and its Implication for Anthropological Study of Culture and Policy Sumahan Bandyopadhyay, MSc, PhD* Department of Anthropology, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore 721102, West Bengal, India *Corresponding author Sumahan Bandyopadhyay, MSc, PhD Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore 721102, West Bengal, India; E-mail: [email protected] Article information Received: May 22nd, 2018; Revised: October 7th, 2018; Accepted: October 25th, 2018; Published: October 30th, 2018 Cite this article Bandyopadhyay S. Apathy, ignorance or natural death? Present state of museums in West Bengal, India and its implication for anthropological study of culture and policy. Anthropol Open J. 2018; 3(1): 18-31. doi: 10.17140/ANTPOJ-3-117 ABSTRACT West Bengal, one of the eastern states of India has the oldest museum in the country apart from housing probably the highest number of museums in India. These museums are showcases of the rich cultural heritage of the country and its development during prehistoric and historical times, artistic and innovative skills of the people, colonial connections and national sentiments. In spite of such a glory and apparent prosperity, the museums in the state are facing a number of problems. It is revealed that many of the museums exist only in name being seldom visited by the common people barring a few connoisseur and researchers. These are run by individual effort and financial support leaving little scope for proper maintenance of objects through appropriate methods of conservation and display. The state neither has a definite policy for the museums, nor does it have any up-to-date data on the number of the museums in the state. -

The List of Vacant Interstate Routes in Between State of Odisha and West

THE LIST OF VACANT INTERSTATE ROUTES IN BETWEEN STATE OF ODISHA & WEST BENGAL . , No. of No. of Nature of SL Distance of the Route in kms. Name of the Routes Permits Trips Service No. Orissa W.B . Total Qdisha Odlih'a 1 , 2 4 5 - ' d 7 8 •• . P , . .4 . .. Angyl to Khejyri via-Kamakhyanagar, Ouburi, 1 300 79 370 2 2 Express Danagadi, Jaleswar, Chandaneswar „ . Balasore to Madhakali via.Jaleswar, 2 70 150 220 3 6 Ordinary Laxmannath . Bahabalpur Muhan to Contai via:Haldipada, 3 65 70 135 2 4 Ordinary Basta, Jalewar, Ambiliatha, Solepeta, Egra • • Baliapal to Contai Via: Gandhi chhak, 4 50 65 115 1 2 Ordinary Jaleswar, Ambiliatha, Egra . Bargarh to Kolkata via: Keonjhar, Anandapur, 5 350 208 558 1 1 Express Bhadrak, Laxmannath • • . Baripada to Contai via: Amarda Road RS. 6 73 90 163 4 8 Ordinary Jaleswar, Laxmannath Baripada to Contai via: Sirsapal, Amarda 7 70 70 140 4 8 Ordinary Road, Jaleswar, Solpeta, Egra. Baripada to Digha via. Kesiary, Rohini, 8 40 120 160 4 8 Ordinary Bogra, Gopiballavpur, Pandachhecha • Baripada to Digha via. Laxmannath, Belda, 9 73 97 170 4 8 Ordinary Egra, Contai Baripada to Midnapur via: Amalkota, 10 35 80 115 2 4 Ordinary Chandua , • • Bhograi to Itaberia via: Thana Chhak, 11 30 80 110 2 4 Ordinary Chandeneswar, Digha, Contai, Madhakhali . • Bhograi to Khejuri via Thanachhak, 12 30 94 124 4 8 Ordinary Chandeneswar, Contai, Heria Bhubaneswar to Bajkul via.Jaleswar, 13 260 105 365 4 4 Express Solepeta, Egra, Bhagabanpur Bhubaneswar to Bajkul via:Balasore, 14 Jaleswar, Laxnannath, Belda, Egra, 260 120 380 4 4 Express Bhagabanpur Chandinipal to Khejuri via: Balasore, 15 202 88 290 1 2 Express Jaleswar, Chandeneswar, Digha, Contai Chandinipal to Khejuri, via:Basudevpur, 16 172 110 282 4 8 Express Haladipada, Jaleswar, Mohanpur, Contai 17 Contai to Bhograi via: Chandaneswar 25 35 60 4 16 Ordinary Contai to Karanjia, via:Egra, Belda, 18 Laxmannath, Jaleswar Amarda Rd, Baripada, 200 80 280 2 2 Express Bisoi. -

Paschim Medinipur

District Sl No Name Post Present Place of Posting WM 1 Dr. Jhuma Sutradhar GDMO Ghatal S. D. Hospital WM 2 Dr. Papiya Dutta GDMO Ghatal S. D. Hospital WM 3 Dr. Sudip Kumar Roy GDMO Jhargram District Hospital WM 4 Dr. Susanta Bera GDMO Jhargram District Hospital Midnapore Medical College & WM 5 Dr. Krishanu Bhadra GDMO Hospital WM 6 Dr. Dipak Kr. Agarwal Specialist G & O Keshiary RH DH & FWS, PASCHIM WM 7 Gouri Sankar Das DPC MEDINIPUR DH & FWS, PASCHIM WM 8 Milan Kumar Choudhury, DAM MEDINIPUR DH & FWS, PASCHIM WM 9 Susanta Nath De DSM MEDINIPUR DH & FWS, PASCHIM WM 10 Sumit Pahari AE MEDINIPUR DH & FWS, PASCHIM WM 11 Tanmoy Patra SAE MEDINIPUR DH & FWS, PASCHIM WM 12 Somnath Karmakar SAE MEDINIPUR Computer DH & FWS, PASCHIM WM 13 Guru Pada Garai Assistant, RCH MEDINIPUR DH & FWS, PASCHIM WM 14 Ramkrishna Roy Account Assistant MEDINIPUR Garhbeta Rural WM 15 Anjan Bera BAM Hospital,Garhbeta - I block Kewakole WM 16 Manimay Panda BAM RH under Garhbeta-II block BH&FWS,Garhbeta-III, At- WM 17 Mrinal Kanti Ghosh BAM Dwarigeria B.P.H.C.,Paschim Medinipur. WM 18 Sohini Das BAM Salboni WM 19 Rajendra Kumar Khan BAM Deypara(Chandra)BPHC WM 20 Dev dulal Rana BAM Keshpur BH & FWS WM 21 Ambar Pandey BAM Binpur RH, Binpur-I BELPAHARI R.H. (BINPUR-II WM 22 AMIT SAHU BAM BH&FWS) CHILKIGARH BPHC UNDER WM 23 AMIT DANDAPAT BAM JAMBONI BLOCK Jhargram BH & FWS, at WM 24 Malay Tung BAM Mohanpur BPHC WM 25 Debapratim Goswami BAM Gopiballavpur-R.H. -

W.B.C.S.(Exe.) Officers of West Bengal Cadre As on 30-11-2016

W.B.C.S.(EXE.) OFFICERS OF WEST BENGAL CADRE AS ON 30-11-2016 Sl Name/Idcode Batch Present Posting Posting Address Mobile/Email No. 1 AMAR 1985 SPECIAL SECRETARY NABANNA,SARAT CHATTERJEE +919836774352 BHATTACHARYYA P & A. R. ROAD ,SHIBPUR, amarbhattacharyya (CS1985017 ) HOWRAH-711102 @yahoo.com 2 OSMAN GANI 1985 SECRETARY WEST BENGAL STATE +919163143210 (CS1985018 ) STATE ELECTION COMMISSION ELECTION COMMISSION ,18, [email protected] SAROJINI NAIDU SARANI om RAODON ST. ,KOLKATA-700017 3 ARUN KUMAR 1985 COMPULSORY WAITING NABANNA ,SARAT CHATTERJEE SINGH P & A. R. ROAD ,SHIBPUR, (CS1985028 ) HOWRAH-711102 4 JANG BAHADUR 1986 ADDL. DIRECTOR, SMALL BERHAMPORE ,MURSHIDABAD SUBBA SAVINGS (CS1986214 ) MURSHIDABAD 5 DURGA KINKAR 1986 SPECIAL SECRETARY NABANNA ,HRBC BUILDING, +919434333986 MAHAPATRA FINANCE 325, SARAT CHATTERJEE (CS1986215 ) ROAD,MANDIRTALA SHIBPUR, HOWRAH-711102 6 DEBAJYOTI 1986 SECRETARY-CUM- MAYUKH BHABAN, SALT LAKE, BHATTACHARYYA CONTROLLER OF EXAM KOLKATA- 700091 ,PHONE: (CS1986219 ) WBSSC 2337-3556 7 GOPAL CH. GHOSE 1986 SPECIAL SECRETARY NAGARAYAN BHAVAN, BLOCK- +919836673222 (CS1986220 ) URBAN DEVELOPMENT DF-8, SECTOR-I,SALT LAKE [email protected] CITY, KOLKATA, WEST BENGAL m 700064 ,PHONE:033 2334 9336 8 ASIM KUMAR 1986 SPECIAL SECRETARY BIKASH BHAVAN, 5TH AND 6TH BHATTARYYA SCHOOL EDUCATION FLOOR DF BLOCK, SECTOR-1, (CS1986222 ) SALT LAKE CITY, KOLKATA, WEST BENGAL 700091 ,PHONE: 23342256 9 BIDYUT 1986 SPECIAL SECRETARY POURA BHAVAN, 4TH FLOOR, BHATTACHARYA ENVIRONMENT FD-415/A, SECTOR-III, (CS1986224 ) BIDHANNAGAR, KOLKATA-700106. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. Pradip Ghosh Aparnapalli, Satbankura, Paschim Medinipur, Pin-721253, West Bengal, India +91-9932318368 M.Tech, PhD Founder Director [email protected] MIDNAPORE CITY COLLEGE www.mcconline.org.in https://www.facebook.com/midnaporecitycollege/ +91-9932318368 PERSONAL DETAILS Date of Birth 27.12.1979 Gender Male Marital Status Married SUMMARY Category General I have the 16 years of past Religion Hindu experience towards promotion of 10 different educational Nationality Indian Institutes as a capacity of director in the district of Paschim Medinipur within the ACADEMIC DETAILS state of West Bengal under name and style of 'Institute of SL. Degree Specialization Year of Institution Board/ % of Science and Technology' the passing University Marks/ only AICTE approved CGPA engineering, college offering M.Tech, B.Tech, Polytechnic,ITI and Management courses. Other educational institutes including four NCTE recognized B. Ed degree college in the name and style of ' Anindita College for Teacher Education', 'Bengal College of Teacher Education', 'Institute for Teacher Education' and 'Excellent Model College for Teacher Education', two NCTE recognized and WBBPE affiliated D. EI.ED Colleges in the name and style of 'Gopsai Avinandan Sangha PTTI’ & ‘College for Teacher Education', AICTE and PCI approved Pharmacy College in the name and style of ‘P.G Institute of Medical Sciences’ offering B.Pharm and D.Pharm courses and UGC recognised and PhD DETAILS Vidyasagar University affiliated General degree College in the PhD Thesis Title Network Security & Cryptography name and style of ‘Midnapore Guide's Name Prof. Sripati Mukhopadhaya City College’ offering different University Department of Computer Application, Undergraduate and Postgraduate programmee in The University of Burdwan, the faculty of Arts, Sciences and Rajbati, Bardhaman, West Bengal, India.