Yona Sabar 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

Iraq Humanitarian Fund (IHF) 1St Standard Allocation 2020 Allocation Strategy (As of 13 May 2020)

Iraq Humanitarian Fund (IHF) 1st Standard Allocation 2020 Allocation Strategy (as of 13 May 2020) Summary Overview o This Allocation Strategy is issued by the Humanitarian Coordinator (HC), in consultation with the Clusters and Advisory Board (AB), to set the IHF funding priorities for the 1st Standard Allocation 2020. o A total amount of up to US$ 12 million is available for this allocation. This allocation strategy paper outlines the allocation priorities and rationale for the prioritization. o This allocation paper also provides strategic direction and a timeline for the allocation process. o The HC in discussion with the AB has set the Allocation criteria as follows; ✓ Only Out-of-camp and other underserved locations ✓ Focus on ICCG priority HRP activities to support COVID-19 Response ✓ Focus on areas of response facing marked resource mobilization challenges Allocation strategy and rationale Situation Overview As of 10 May 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) has confirmed 2,676 cases of COVID-19 in Iraq; 107 fatalities; and 1,702 patients who have recovered from the virus. The Government of Iraq (GOI) and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) have generally relaxed enforcement of the stringent curfews and movement restrictions which have been in place for several weeks, although they are nominally still applicable. Partial lockdowns are currently in force in federal Iraq until 22 May, and in Kurdistan Region of Iraq until 18 May. The WHO and the Ministry of Health recommend maintenance of strict protective measures for all citizens to prevent a resurgence of new cases in the country. The humanitarian community in Iraq is committed to both act now to stem the impact of COVID-19 by protecting those most at risk in already vulnerable humanitarian contexts and continue to support existing humanitarian response plans, in increasingly challenging environments. -

IDP and Refugee Camp Locations - As of January 2017

For Humanitarian Purposes Only IRAQ Production date: 01 February 2017 IDP and Refugee Camp Locations - As of January 2017 Za k ho T U R K E Y Darkar ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑⛳⚑Bersive II Chamishku Bersive I Dawudiya ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Am e di Bajet Kandala ² Rwanga Dahuk Community Me r ga s ur Da h uk Su m el So r an !PDahuk Kabrato I+II Ak r e Khanke ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Shariya S Y R I A ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Sh i kh a n Domiz I+II Essian Akre ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Sheikhan Amalla ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Garmawa ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑Mamrashan ⛳⚑ Mamilian ⛳⚑Nargizlia Ch o ma n 1 + 2 Tel af ar Ti lk a if Qaymawa ⛳⚑ Basirma ⛳⚑ Bardarash Darashakran ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Sh a ql a w a Si n ja r Hasansham M2 Gawilan Kawergosk Mosul!P ⛳⚑ I R A N Hasansham U3 ⛳⚑⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Baharka ⛳⚑ Ps h da r Ha m da n iy a Khazer M1 Ra n ia Harsham ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Erbil Ankawa 2 !P Erbil Mo s ul Ninewa Er b il Ko i sn j aq Qushtapa ⛳⚑ Do k an Debaga 1 ⛳⚑ Debaga 4 ⛳⚑⛳⚑ Surdesh Debaga Debaga 2 ⛳⚑ Stadium Ba 'a j Hasiyah ⛳⚑ Tina ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Qayyarah-Jad'ah Sh a rb a zh e r Pe n jw i n Ma k hm u r Ki r ku k Da b es Sulaymaniyah !P Barzinja Kirkuk ⛳⚑ Su l ay m an i y ah Ha t ra !P Arbat IDP ⛳⚑ Sh i rq a t ⛳⚑ Ashti IDP Nazrawa ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑Arbat Refugee Yahyawa ⛳⚑⛳⚑ Laylan 1 Sulaymaniyah Ha w ig a Kirkuk Da r ba n d ih k an Daquq ⛳⚑ Ch a mc h a ma l Laylan 2 ⛳⚑ Ha l ab j a Da q uq Ka l ar Hajjaj Camp ⛳⚑ Al-Alam ⛳⚑⛳⚑2 (MoMD) Ba i ji Al Alam 1 To oz (UNHCR) Tik r it Tazade ⛳⚑Al Safyh ⛳⚑ ⛳⚑ Tikrit Ru 'u a University Qoratu ⛳⚑ Al Obaidi Ki f ri ⛳⚑ Salah al-Din Da u r Ka 'i m Al Wand 1 Al Wand 2⛳⚑ Ha d it h a Sa m ar r a Al Abassia Al-Hawesh ⛳⚑ Kh a na q in ⛳⚑ !P Samarra Al-Iraq Al-Hardania Al-Muahad ⛳⚑ Diyala ⛳⚑ -

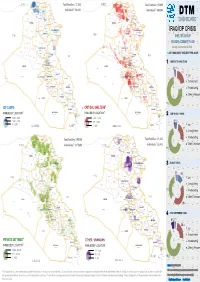

20141214 04 IOM DTM Repor

TURKEY Zakho Amedi Total Families: 27,209 TURKEY Zakho Amedi TURKEY Total Families: 113,999 DAHUK Mergasur DAHUK Mergasur Dahuk Sumel 1 Sumel Dahuk 1 Soran Individual : 163,254 Soran Individuals : 683,994 DTM Al-Shikhan Akre Al-Shikhan Akre Tel afar Choman Telafar Choman Tilkaif Tilkaif Shaqlawa Shaqlawa Al-Hamdaniya Rania Al-Hamdaniya Rania Sinjar Pshdar Sinjar Pshdar ERBIL ERBIL DASHBOARD Erbil Erbil Mosul Koisnjaq Mosul Koisnjaq NINEWA Dokan NINEWA Dokan Makhmur Sharbazher Penjwin Makhmur Sharbazher Penjwin Dabes Dabes IRAQ IDP CRISIS Al-Ba'aj SULAYMANIYAH Al-Ba'aj SULAYMANIYAH Hatra Al-Shirqat Kirkuk Hatra Al-Shirqat Kirkuk Sulaymaniya Sulaymaniya KIRKUK KIRKUK Al-Hawiga Chamchamal Al-Hawiga Chamchamal DarbandihkanHalabja SYRIA Darbandihkan SYRIA Daquq Daquq Halabja SHELTER GROUP Kalar Kalar Baiji Baiji Tooz Tooz BY DISPLACEMENT FLOW Ra'ua Tikrit SYRIA Ra'ua Tikrit Kifri Kifri January to December 9, 2014 SALAH AL-DIN Haditha Haditha SALAH AL-DIN Samarra Al-Daur Khanaqin Samarra Al-Daur Khanaqin Al-Ka'im Al-Ka'im Al-Thethar Al-Khalis Al-Thethar Al-Khalis % OF FAMILIES BY SHELTER TYPE AS OF: DIYALA DIYALA Ana Balad Ana Balad IRAN Al-Muqdadiya IRAN Al-Muqdadiya IRAN Heet Al-Fares Heet Al-Fares Tar m ia Tarm ia Ba'quba Ba'quba Adhamia Baladrooz Adhamia Baladrooz Kadhimia Kadhimia JANUARY TO MAY CRISIS KarkhAl Resafa Ramadi Ramadi KarkhAl Resafa 1 Abu Ghraib Abu Ghraib BAGHDADMada'in BAGHDADMada'in ANBAR Falluja ANBAR Falluja Mahmoudiya Mahmoudiya Badra Badra 2% 1% Al-Azezia Al-Azezia Al-Suwaira Al-Suwaira Al-Musayab Al-Musayab 21% Al-Mahawil -

The Martyrs St

November 1st, 2015 1st Sunday of the Church SAINTS OF THE WEEK SPECIAL EDITION: THE MARTYRS ST. ISAAC OF NINEVEH Father Ragheed Ganni was a Chaldean priest who was studying at the Irish College when the US invaded Iraq. He asked his bishop for permission to return to be with his people, and afterwards, he had received many death threats. In 2007, after the evening liturgy in Mosul’s Holy Spirit Chaldean Church, Father Ragheed was leaving together with three subdeacons. His car was stopped by gun men, although he was smiling, laughing, and trying to He was born in the region of engage with them. They said they will teach him to Beth Qatraye in Eastern Arabia. laugh and cut him in half with machine gun fire. He When still quite young, he was martyred along with the three subdeacons. entered a monastery where he devoted his energies towards the At the time of this murder, Father Ragheed was practice of asceticism. After secretary to Paolos Faraj Rahho, the archbishop of many years of studying at the library attached to the Mosul. Bishop Rahho was murdered only nine monastery, he emerged as an months after Father Ragheed in the same city of authoritative figure in theology. Mosul. The Chaldean Church immediately mourned Shortly after, he dedicated his them as martyrs, and Pope Benedict XVI life to monasticism and became immediately prayed for them from Rome. involved in religious education throughout the Beth Qatraye Sister Cecilia had belonged to the Order of the region. When the Catholicos Sacred Heart of Jesus and had devoted her life to Georges (680–659) visited Beth ministering to the poor and ill. -

Iraq Master List Report 114 January – February 2020

MASTER LIST REPORT 114 IRAQ MASTER LIST REPORT 114 JANUARY – FEBRUARY 2020 HIGHLIGHTS IDP individuals 4,660,404 Returnee individuals 4,211,982 4,596,450 3,511,602 3,343,776 3,030,006 2,536,734 2,317,698 1,744,980 1,495,962 1,399,170 557,400 1,414,632 443,124 116,850 Apr Jun Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb Apr June Aug Oct Dec Feb 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Figure 1. Number of IDPs and returnees over time Data collection for Round 114 took place during the months of January were secondary, with 5,910 individuals moving between locations of and February 2020. As of 29 February 2020, DTM identified 4,660,404 displacement, including 228 individuals who arrived from camps and 2,046 returnees (776,734 households) across 8 governorates, 38 districts and individuals who were re-displaced after returning. 2,574 individuals were 1,956 locations. An additional 63,954 returnees were recorded during displaced from their areas of origin for the first time. Most of them fled data collection for Report 114, which is significantly lower than the from Baghdad and Diyala governorates due to ongoing demonstrations, number of new returnees in the previous round (135,642 new returnees the worsening security situation, lack of services and lack of employment in Report 113). Most returned to the governorates of Anbar (26,016), opportunities. Ninewa (19,404) and Salah al-Din (5,754). -

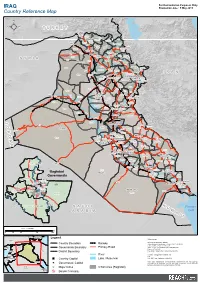

Country Reference Map

For Humanitarian Purposes Only IRAQ Production date : 5 May 2015 Country Reference Map T U R K E Y Ibrahim Al-Khalil (Habour) Zakho Zakho Amedi Dahuk Amedi Mergasur Dahuk Sumel Dahuk Rabia Mergasur Soran Sumel Shikhan Akre Haji Omaran Shikhan Akre Soran Telafar Choman Tilkaif Tilkaif Choman Shaqlawa Telafar Shaqlawa Sinjar Mosul Hamdaniya Rania Pshdar Sinjar Hamdaniya Erbil Ranya Qalat Erbil Dizah SYRIA Ba'aj Koisnjaq Mosul Erbil Ninewa Koisnjaq Dokan Baneh Dokan Makhmur Sharbazher Ba'aj Chwarta Penjwin Dabes Makhmur Penjwin Hatra Dabes Kirkuk Sulaymaniyah Chamchamal Shirqat Kirkuk IRAN Sulaymaniyah Hatra Shirqat Hawiga Daquq Sulaymaniyah Kirkuk Halabja Hawiga Chamchamal Darbandihkan Daquq Halabja Halabja Darbandikhan Baiji Tooz Khourmato Kalar Tikrit Baiji Tooz Ru'ua Kifri Kalar Tikrit Ru'ua Ka'im Salah Daur Kifri Ka'im Ana Haditha Munthiriya al-Din Daur Khanaqin Samarra Samarra Ka'im Haditha Khanaqin Balad Khalis Diyala Thethar Muqdadiya Balad Ana Al-Dujayl Khalis Muqdadiya Ba`aqubah Mandali Fares Heet Heet Ba'quba Baladrooz Ramadi Falluja Baghdad J Ramadi Rutba Baghdad Badra O Baramadad Falluja Badra Anbar Suwaira Azezia Turaybil Azezia R Musayab Suwaira Musayab D Ain Mahawil Al-Tamur Kerbala Mahawil Wassit Rutba Hindiya Na'miya Kut Ali Kerbala Kut Al-Gharbi A Ain BabylonHilla Al-Tamur Hindiya Ali Hashimiya Na'maniya Al-Gharbi Hashimiya N Kerbala Hilla Diwaniya Hai Hai Kufa Afaq Kufa Diwaniya Amara Najaf Shamiya Afaq Manathera Amara Manathera Qadissiya Hamza Rifa'i Missan Shamiya Rifa'i Maimouna Kahla Mejar Kahla Al-Kabi Qal'at Hamza -

IRAQ: Camp Closure Status Date: 14 January 2021

IRAQ: Camp Closure Status Date: 14 January 2021 Date of Departures Site closed Governorate District Site Name 1 Site Type Population3 closure/change 2 (ind.) TURKEY Under closure Al-Sulaymaniyah Al-Sulaymaniyah Ashti IDP Camp No closure announced* 8,865 Closure paused Al-Sulaymaniyah Kalar Tazade Camp No closure announced* 1,031 Zakho No closure announced Baghdad Al-Mahmoudiya Latifiya 1**** Camp No closure announced* 126 Camp population Baghdad Al-Mahmoudiya Latifiya 2**** Camp No closure announced* 58 Duhok Al-Amadiya Dawadia Camp No closure announced* 2,577 Al-Amadiya 22,583 Sumail Al-Zibar Duhok Sumail Bajet Kandala Camp No closure announced* 8,549 10,000 Duhok Sumail Rwanga Community Camp No closure announced* 12,759 Duhok Sumail Kabarto 2 Camp No closure announced* 11,120 Aqra Rawanduz 2,500 Telafar Duhok Sumail Khanke Camp No closure announced* 14,210 Tilkaef Duhok Sumail Shariya Camp No closure announced* 15,217 Al-Shikhan Shaqlawa Duhok Sumail Kabarto 1 Camp No closure announced* 11,873 Al-Hamdaniya Duhok Zakho Berseve 1 Camp No closure announced* 5,712 Sinjar Erbil Rania Pshdar Duhok Zakho Berseve 2 Camp No closure announced* 7,126 Khazer Camp Hamam Al Ali 2 Camp Duhok Zakho Chamishku Camp No closure announced* 22,583 Erbil Al-Mosul Duhok Zakho Darkar Camp No closure announced* 3,358 Al Salamyiah Camp Qayyarah-Jad’ah 5 Camp Koysinjaq Erbil Erbil Baharka Camp No closure announced* 4,528 Dokan Sharbazher Erbil Erbil Harshm Camp No closure announced* 1,434 Qayyarah-Jad’ah 1 Camp Panjwin Erbil Makhmour Debaga 1 Camp No closure announced* -

UNHCR Mosul Weekly Protection

MOSUL WEEKLY PROTECTION UPDATE 24 - 30 November 2017 HIGHLIGHTS: • Secondary displacement accounts for the majority of the new arrivals to camps as economic and intercommunal tensions continue to force families into camps. • UNHCR has facilitated the issuance of more than 7,000 civil documents since October 2016, while more than 50,000 documents have been identified as missing among displaced individuals. • More than 7,000 Iraqi returnees from Al Hol camp in Syria returned to camps in the south of Mosul in Ninewa Governorate this week pending their return to areas of origin once cleared. TURKEY K KEY FIGURES: Dahuk K ! ! !! ! ! ! 1.5 million people expec t ed to be impacted in Mosul ! ! ! Mosul and surrounding areas ! ! ! K N !! ! 793,422 people currently displaced 300,576 ! ! Ninewa ! Erbil !! ! ! ! !! !! ! Governorate of displacement ! ! ! E ! W ! Sulaymaniyah 0.02% ! ! Babylon 0.05% K Kirkuk Sulaymaniyah Erbil 0.12% S ! SYRIA ! Anbar 0.33% Salah al-Din 1.46% LEGEND ! ! IDP ! ! Baghdad 4.40% K ! ! Ninewa 93.5% Return route K ! IDP Camp ! Salah al-Din Returnees IRAN 55,499 Families assessed 263,581 Individuals Diyala K Wassit Anbar K Kerbala Babylon Baghdad Missan 72,375 74,475 62,316 54,415 90% of families with no income 1,302 unaccompanied or separated children K 0 100 Wassit 30% Babylon Sources: Esri, HERE, DeLorme, increment P Corp., NPS, NRCan, Ordnance Survey, © OpenStreetMap contributors, USGS, NGA, NASA, 4,688 families referred for cash assistance CGIAR, N Robinson, NCEAS, NLS, OS, NMA, Geodatastyrelsen, Rijkswaterstaat, GSA, -

COI QUERY Disclaimer

COI QUERY Country of Origin/Topic Iraq Question(s) What is the security context and treatment of Christians in Iraq? 1. Background 1.1. Post-ISIL security context of Christian community - Targeted destruction of infrastructure and habitat - Targeting of Christians by armed actors 1.2. Ninewa governorate and ability to secure law and order - Governance, education and practice of Christianity in Iraq 1.3. Missing, IDPs and returnees Date of completion 22 October 2020 Query Code Q 21 Contributing EU+ COI This query response was sent to the EASO COI Specialists Network units (if applicable) on Iraq1 for contributions on the security context and treatment of Yazidis. No information was contributed by EU+ countries, but feedback was received from the Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre (Landinfo). Disclaimer This response to a COI query has been elaborated according to the Common EU Guidelines for Processing COI and EASO COI Report Methodology. The information provided in this response has been researched, evaluated and processed with utmost care within a limited time frame. All sources used are referenced. A quality review has been performed in line with the above mentioned methodology. This document does not claim to be exhaustive neither conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to international protection. If a certain event, person or organisation is not mentioned in the report, this does not mean that the event has not taken place or that the person or organisation does not exist. Terminology used should not be regarded as indicative of a particular legal position. The information in the response does not necessarily reflect the opinion of EASO and makes no political statement whatsoever. -

Zakho Days: Travels with the General

NOT FOR PUBLICATION WITHOUT WRITER'S CONSENT INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS tog-7 Peter Byrd Martin I CWA Crane Rogers /+ %lest 4hee Iock Street Hanover NH June 26th 1991 Dear Peter, Here is an excerpt from my journeys in Kurdistan, an unfinished piece I submit to you without further comment, entitled: by Thomas Go ltz We first met in the Baghdad Hotel, the shabby new home away from home I had arranged for the staff of the International Rescue Committee in Zakho, northern Iraq. "This is Kek Aziz," my newly appointed manager, Mister Shukri, bashfully informed me, "He is my oldest and dearest friend, and he needs a shower." The stocky, older man was dressed in baggy shaar pants, a khaki shirt and wore a skull cap and when he opened his mouth to speak he revealed an upper jaw devoid of teeth. "Hello," he said, clicking his feet together in some manner of military salute while extending his hand, "I have not bathed in three weeks." It was only my second night as the director of the hotel, and was more than a little hesitant about letting in an aging .Peer.gah into my showers. A down-town dump, the Baghdad consisted of thirteen rooms and a roof, and prior to my taking possession it had served as the barracks for the last Iraqi troops in the city before they had withdrawn, surrendering the Zakho to the Americans. And in leaving, they seemed to have wanted to make it as uncomfortable as possible for any future tenants. The place had been trashed--curtains ripped, mattresses defiled, windows smashed. -

Displacement and Returns to Sinjar and Al-Ba'aj Districts

DTMDISPLACEMENT EMERGENCY AND RETURNS TO SINJAR TRACKINGAND AL-BA’AJ DISTRICTS DISPLACEMENT AND RETURNS TO PERIOD COVERED: SINJAR AND AL-BA’AJ DISTRICTS 17 TO 29 OCTOBER 2020 *All charts/graphs in this document show total figures for the period of 8 June to 29 October 2020 Between 17 and 29 October 2020, DTM tracked 2,803 individuals (546 families) returning to Sinjar and Al-Ba’aj districts in Iraq’s Ninewa Governorate. This brings the 34,164 74% 26% total number of individuals who have taken this route to 34,164 (6,405 families) since INDIVIDUALS Returnees Out-of-camp data collection commenced on 8 June 2020. IDPs 6,405 In this reporting period, the average number of daily individual arrivals was 192 to Sinjar FAMILIES and 23 to Al-Ba’aj. In this period, the daily number of arrivals to Sinjar is lower than the overall daily average since 8 June (219), while the daily average number of arrivals to Moved to Sinjar and 91% 9% Al-Ba’aj districts to Sinjar to Al-Ba’aj Al-Ba’aj is consistent with overall average since 8 June (22). Of those individuals who returned between 17 and 29 October, a total of 2,501 were recorded in Sinjar (89%) and 390 were recorded in Al-Ba’aj (11%) – broadly consistent 81% 18% <1% <1% with the rates of individuals’ districts of arrival since 8 June. The most common sub-district of arrival was Al-Shamal with 1,233 individuals (44%), from Dahuk from Ninewa from Erbil from Sulaymaniyah followed by Qaeyrrawan with 645 individuals (23%), and Markaz Sinjar with 623 indi- viduals (22%).