Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heads Or Tails

Heads or Tails Representation and Acceptance in Hadrian’s Imperial Coinage Name: Thomas van Erp Student number: S4501268 Course: Master’s Thesis Course code: (LET-GESM4300-2018-SCRSEM2-V) Supervisor: Mw. dr. E.E.J. Manders (Erika) 2 Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................ 5 Figure 1: Proportions of Coin Types Hadrian ........................................................................ 5 Figure 2: Dynastic Representation in Comparison ................................................................ 5 Figure 3: Euergesia in Comparison ....................................................................................... 5 Figure 4: Virtues ..................................................................................................................... 5 Figure 5: Liberalitas in Comparison ...................................................................................... 5 Figure 6: Iustitias in Comparison ........................................................................................... 5 Figure 7: Military Representation in Comparison .................................................................. 5 Figure 8: Divine Association in Comparison ......................................................................... 5 Figure 9: Proportions of Coin Types Domitian ...................................................................... 5 Figure 10: Proportions of Coin Types Trajan ....................................................................... -

Kenai Fjords Fact Sheet

National Park Service Kenai Fjords U.S. Department of the Interior Kenai Fjords National Park www.nps.gov/KenaiFjords Fact Sheet Purpose Kenai Fjords was established to maintain unimpaired the scenic and environmental integrity of the Harding Icefield, its outflowing glaciers and coastal fjords and islands in their natural state; and to protect seals, sea lions, other marine mammals, and marine and other birds and to maintain their hauling and breeding areas in their natural state, free of human activity which is disruptive to their natural processes. Established December 1, 1978 ....................... Designated as a National Monument by President Carter December 2, 1980 ....................... Designated as a National Park through the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA). Size Legislative boundary................ 669,983 acres or ~ 1047 square miles Managed by NPS ...................... 603,130 acres or ~ 940 square miles Eligible Wilderness ................... 569,000 acres or ~ 889 square miles Visitation 303,000 recreation visits in 2017 Employment NPS Permanent Employees ..... 31 NPS Seasonal Employees ......... 50 NPS Volunteers ......................... 26 volunteers contributed 2,417 hours of service in 2017 Budget 2017 base appropriations $3.9 million Campground 12 campsites in the Exit Glacier area, with 2 wheelchair accessible sites. Campground is tent-only, and available on a first come, first serve basis. Vehicle camping is strictly prohibited. Backcountry camping is allowed throughout the park except within 500 feet of a public use cabin or within 1/8 mile of a road or trail at Exit Glacier. Public Use Cabins Aialik and Holgate: available for reservation during the summer months through Recreation.gov. Willow: available during winter months by contacting the park. -

The Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 44 (2007)

THE BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PapYROLOGIsts Volume 44 2007 ISSN 0003-1186 The current editorial address for the Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists is: Peter van Minnen Department of Classics University of Cincinnati 410 Blegen Library Cincinnati, OH 45221-0226 USA [email protected] The editors invite submissions not only fromN orth-American and other members of the Society but also from non-members throughout the world; contributions may be written in English, French, German, or Italian. Manu- scripts submitted for publication should be sent to the editor at the address above. Submissions can be sent as an e-mail attachment (.doc and .pdf) with little or no formatting. A double-spaced paper version should also be sent to make sure “we see what you see.” We also ask contributors to provide a brief abstract of their article for inclusion in L’ Année philologique, and to secure permission for any illustration they submit for publication. The editors ask contributors to observe the following guidelines: • Abbreviations for editions of papyri, ostraca, and tablets should follow the Checklist of Editions of Greek, Latin, Demotic and Coptic Papyri, Ostraca and Tablets (http://scriptorium.lib.duke.edu/papyrus/texts/clist.html). The volume number of the edition should be included in Arabic numerals: e.g., P.Oxy. 41.2943.1-3; 2968.5; P.Lond. 2.293.9-10 (p.187). • Other abbreviations should follow those of the American Journal of Ar- chaeology and the Transactions of the American Philological Association. • For ancient and Byzantine authors, contributors should consult the third edition of the Oxford Classical Dictionary, xxix-liv, and A Patristic Greek Lexi- con, xi-xiv. -

Seward Historic Preservation Plan

City of Seward City Council Louis Bencardino - Mayor Margaret Anderson Marianna Keil David Crane Jerry King Darrell Deeter Bruce Siemenski Ronald A. Garzini, City Manager Seward Historic Preservation Commissioners Doug Capra Donna Kowalski Virginia Darling Faye Mulholland Jeanne Galvano Dan Seavey Glenn Hart Shannon Skibeness Mike Wiley Project Historian - Anne Castellina Community Development Department Kerry Martin, Director Rachel James - Planning Assistant Contracted assistance by: Margaret Branson Tim Sczawinski Madelyn Walker Funded by: The City of Seward and the Alaska Office of History and Archaeology Recommended by: Seward Historic Preservation Commission Resolution 96-02 Seward Planning and Zoning Commission Resolution 96-11 Adopted by: Seward City Council Resolution 96-133 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction......................................................................................................................................1 Purpose of the Plan ..............................................................................................................1 Method .................................................................................................................................2 Goals for Historic Preservation............................................................................................3 Community History and Character ..................................................................................................4 Community Resources...................................................................................................................20 -

Steve Mccutcheon Collection, B1990.014

REFERENCE CODE: AkAMH REPOSITORY NAME: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center Bob and Evangeline Atwood Alaska Resource Center 625 C Street Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-929-9235 Fax: 907-929-9233 Email: [email protected] Guide prepared by: Sara Piasecki, Archivist TITLE: Steve McCutcheon Collection COLLECTION NUMBER: B1990.014 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Dates: circa 1890-1990 Extent: approximately 180 linear feet Language and Scripts: The collection is in English. Name of creator(s): Steve McCutcheon, P.S. Hunt, Sydney Laurence, Lomen Brothers, Don C. Knudsen, Dolores Roguszka, Phyllis Mithassel, Alyeska Pipeline Services Co., Frank Flavin, Jim Cacia, Randy Smith, Don Horter Administrative/Biographical History: Stephen Douglas McCutcheon was born in the small town of Cordova, AK, in 1911, just three years after the first city lots were sold at auction. In 1915, the family relocated to Anchorage, which was then just a tent city thrown up to house workers on the Alaska Railroad. McCutcheon began taking photographs as a young boy, but it wasn’t until he found himself in the small town of Curry, AK, working as a night roundhouse foreman for the railroad that he set out to teach himself the art and science of photography. As a Deputy U.S. Marshall in Valdez in 1940-1941, McCutcheon honed his skills as an evidential photographer; as assistant commissioner in the state’s new Dept. of Labor, McCutcheon documented the cannery industry in Unalaska. From 1942 to 1944, he worked as district manager for the federal Office of Price Administration in Fairbanks, taking photographs of trading stations, communities and residents of northern Alaska; he sent an album of these photos to Washington, D.C., “to show them,” he said, “that things that applied in the South 48 didn’t necessarily apply to Alaska.” 1 1 Emanuel, Richard P. -

Easy Comeback for Skalleti

MONDAY, 22 MARCH 2021 MOGUL ON SONG FOR SHEEMA CLASSIC EASY COMEBACK Mogul (GB) (Galileo {Ire}) is in good form ahead of a start in FOR SKALLETI the $5-million G1 Dubai Sheema Classic at Meydan on Mar. 27. Last seen in action taking the G1 Longines Hong Kong Vase at Sha Tin in December, the Coolmore partners-owned 4-year-old also saluted in the 2020 G3 Gordon S. at Goodwood in July, ran second in the Aug. 19 Great Voltigeur S. and returned to the winner=s circle in the G1 Juddmonte Grand Prix de Paris at ParisLongchamp in September. Fifth in the GI Longines Breeders= Cup Turf a month prior to his Hong Kong triumph, the 3.4- million gns Tattersalls October Book 1 yearling will fly to Dubai on Monday and step out for morning trackwork after clearing 48 hours of quarantine on Thursday. AWe=re happy with everything he=s done,@ trainer Aidan O=Brien, who won the race with the late St Nicholas Abbey (Ire) (Montjeu {Ire}) in 2013, told the Tamarkuz Media notes team. Skalleti & Pierre-Charles Boudot winning for fun in the Prix Exbury Cont. p3 Scoop Dyga Freshened up since his foray to Sha Tin for the G1 Hong Kong IN TDN AMERICA TODAY Cup, Jean-Claude Seroul=s Skalleti (Fr) (Kendargent {Fr}) was all TIME TO BRING BACK DOWNHILL RACING AT SA class in Saint-Cloud=s deep ground as he sauntered to a In the latest The Week in Review, Bill Finley calls for the turn of confidence-restoring win in the G3 Prix Exbury. -

Exit Glacier Area Plan Environmental Assessment and General Management Plan Amendment

Kenai Fjords National Park Exit Glacier Area Plan Environmental Assessment and General Management Plan Amendment May 2004 iîl/ rztsoy United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE K-cnai i-jords National Park P O Box 172? Seward, Alaska 9%64 L7617 (AKSO-RER) April 12, 2004 Dear Public Reviewer, Enclosed for your information and review is the environmental assessment (EA) for the Exit Glacier Area Plan in Kcnai Fjords National Park. The EA was completed in accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, and the regulations of the Council on Environmental Quality (40CFR 1508.9). The environmental assessment also is available for review at the following website: www.nps.gov/kefi/home.htm and click on Park Issues. Public comments on the environmental assessment will be accepted from May 3 to June 1, 2004. Written comments on the environmental assessment may be addressed to: Kenai Fjords National Park Attn: EG Plan P.O. Box 1727 Seward, Alaska 99664 Email: [email protected] Thank you for your interest in Kenai Fjords National Park. Anne Castellina Superintendent ) Exit Glacier Area Plan Environmental Assessment and General Management Plan Amendment Kenai Fjords National Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Seward, AK M ay 2004 Exit Glacier Area Plan SUMMARY The National Park Service (NPS) developed this Exit Glacier Area Plan/ Environmental Assessment and General Management Plan Amendment to provide guidance on the management of the Exit Glacier area of Kenai Fjords National Park over the next 20 years. The approved plan will provide a framework for proactive decision making on such issues as natural and cultural resources, visitor use, and park development, which will allow park managers to effectively address future problems and opportunities. -

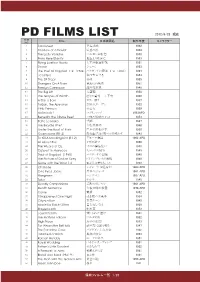

Pd Films List 0824

PD FILMS LIST 2012/8/23 現在 FILM Title 日本映画名 制作年度 キャラクター NO 1 Sabouteur 逃走迷路 1942 2 Shadow of a Doubt 疑惑の影 1943 3 The Lady Vanishe バルカン超特急 1938 4 From Here Etanity 地上より永遠に 1953 5 Flying Leather Necks 太平洋航空作戦 1951 6 Shane シェーン 1953 7 The Thief Of Bagdad 1・2 (1924) バクダッドの盗賊 1・2 (1924) 1924 8 I Confess 私は告白する 1953 9 The 39 Steps 39夜 1935 10 Strangers On A Train 見知らぬ乗客 1951 11 Foreign Correspon 海外特派員 1940 12 The Big Lift 大空輸 1950 13 The Grapes of Wirath 怒りの葡萄 上下有 1940 14 A Star Is Born スター誕生 1937 15 Tarzan, the Ape Man 類猿人ターザン 1932 16 Little Princess 小公女 1939 17 Mclintock! マクリントック 1963APD 18 Beneath the 12Mile Reef 12哩の暗礁の下に 1953 19 PePe Le Moko 望郷 1937 20 The Bicycle Thief 自転車泥棒 1948 21 Under The Roof of Paris 巴里の屋根の根 下 1930 22 Ossenssione (R1.2) 郵便配達は2度ベルを鳴らす 1943 23 To Kill A Mockingbird (R1.2) アラバマ物語 1962 APD 24 All About Eve イヴの総て 1950 25 The Wizard of Oz オズの魔法使い 1939 26 Outpost in Morocco モロッコの城塞 1949 27 Thief of Bagdad (1940) バクダッドの盗賊 1940 28 The Picture of Dorian Grey ドリアングレイの肖像 1949 29 Gone with the Wind 1.2 風と共に去りぬ 1.2 1939 30 Charade シャレード(2種有り) 1963 APD 31 One Eyed Jacks 片目のジャック 1961 APD 32 Hangmen ハングマン 1987 APD 33 Tulsa タルサ 1949 34 Deadly Companions 荒野のガンマン 1961 APD 35 Death Sentence 午後10時の殺意 1974 APD 36 Carrie 黄昏 1952 37 It Happened One Night 或る夜の出来事 1934 38 Cityzen Ken 市民ケーン 1945 39 Made for Each Other 貴方なしでは 1939 40 Stagecoach 駅馬車 1952 41 Jeux Interdits 禁じられた遊び 1941 42 The Maltese Falcon マルタの鷹 1952 43 High Noon 真昼の決闘 1943 44 For Whom the Bell tolls 誰が為に鐘は鳴る 1947 45 The Paradine Case パラダイン夫人の恋 1942 46 I Married a Witch 奥様は魔女 -

The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China

Liberal Barbarism: The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China Ringmar, Erik 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Ringmar, E. (2013). Liberal Barbarism: The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China. Palgrave Macmillan. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 Part I Introduction 99781137268914_02_ch01.indd781137268914_02_ch01.indd 1 77/16/2013/16/2013 1:06:311:06:31 PPMM 99781137268914_02_ch01.indd781137268914_02_ch01.indd 2 77/16/2013/16/2013 1:06:321:06:32 PPMM Chapter 1 Liberals and Barbarians Yuanmingyuan was the palace of the emperor of China, but that is a hope lessly deficient description since it was not just a palace but instead a large com- pound filled with hundreds of different buildings, including pavilions, galleries, temples, pagodas, libraries, audience halls, and so on. -

Desktop Biodiversity Report

Desktop Biodiversity Report Land at Balcombe Parish ESD/14/747 Prepared for Katherine Daniel (Balcombe Parish Council) 13th February 2014 This report is not to be passed on to third parties without prior permission of the Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre. Please be aware that printing maps from this report requires an appropriate OS licence. Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre report regarding land at Balcombe Parish 13/02/2014 Prepared for Katherine Daniel Balcombe Parish Council ESD/14/74 The following information is included in this report: Maps Sussex Protected Species Register Sussex Bat Inventory Sussex Bird Inventory UK BAP Species Inventory Sussex Rare Species Inventory Sussex Invasive Alien Species Full Species List Environmental Survey Directory SNCI M12 - Sedgy & Scott's Gills; M22 - Balcombe Lake & associated woodlands; M35 - Balcombe Marsh; M39 - Balcombe Estate Rocks; M40 - Ardingly Reservior & Loder Valley Nature Reserve; M42 - Rowhill & Station Pastures. SSSI Worth Forest. Other Designations/Ownership Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty; Environmental Stewardship Agreement; Local Nature Reserve; National Trust Property. Habitats Ancient tree; Ancient woodland; Ghyll woodland; Lowland calcareous grassland; Lowland fen; Lowland heathland; Traditional orchard. Important information regarding this report It must not be assumed that this report contains the definitive species information for the site concerned. The species data held by the Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre (SxBRC) is collated from the biological recording community in Sussex. However, there are many areas of Sussex where the records held are limited, either spatially or taxonomically. A desktop biodiversity report from SxBRC will give the user a clear indication of what biological recording has taken place within the area of their enquiry. -

Foundation Document Overview, Kenai Fjords National Park, Alaska

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Kenai Fjords National Park Alaska Contact Information For more information about the Kenai Fjords National Park Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or (907) 422-0500 or write to: Superintendent, Kenai Fjords National Park, P.O. Box 1727, Seward, AK 99664 Significance and Purpose Fundamental Resources and Values Significance statements express why Kenai Fjords National Park resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. Fundamental resources and values are those features, systems, processes, experiences, stories, scenes, sounds, smells, or other attributes determined to merit primary consideration during planning and management processes because they are essential to achieving the purpose of the park and maintaining its significance. Icefields and Glaciers: Kenai Fjords National Park protects the Harding Icefield and its outflowing glaciers, where the maritime climate and mountainous topography result in the formation and persistence of glacier ice. The purpose of KENAI FJORDS NATIONAL PARK • Icefields is to preserve the scenic and environmental • Climate Processes integrity of an interconnected icefield, glacier, • Exit Glacier and coastal fjord ecosystem. • Science & Education Fjords: Kenai Fjords National Park protects wild and scenic fjords that open to the Gulf of Alaska where rich currents meet glacial outwash to sustain an abundance of marine life. -

Wildlife Strikes to Civil Aircraft in the United States, 1990-2020

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE U.S. DEPARTMENT WILDLIFE SERVICES OF TRANSPORTATION FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION Smithsonian Feather Lab identifies Cerulean Warbler struck by aircraft on April 28, 2020 as the 600th species of bird in the National Wildlife Strike Database The U.S. Departments of Transportation and Agriculture prohibit discrimination in all their programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status (not all prohibited bases apply to all programs). Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact the appropriate agency. The Federal Aviation Administration produced this report in cooperation with the U. S. Department of Agriculture, Wildlife Services, under an interagency agreement (692M15- 19-T-00017). The purpose of this agreement is to 1) document wildlife strikes to civil aviation through management of the FAA National Wildlife Strike Database and 2) research, evaluate, and communicate the effectiveness of various habitat management and wildlife control techniques for minimizing wildlife strikes with aircraft at and away from airports. These activities provide a scientific basis for FAA policies, regulatory decisions, and recommendations regarding airport safety and wildlife. Authors Richard A. Dolbeer, Science Advisor, Airport Wildlife Hazards Program, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Wildlife Services, 6100 Columbus Ave., Sandusky, OH 44870 Michael J. Begier, National Coordinator, Airport Wildlife Hazards Program, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Wildlife Services, 1400 Independence Ave., SW, Washington, DC 20250 Phyllis R. Miller, National Wildlife Strike Database Manager, Airport Wildlife Hazards Program, U.S.