The Edges of Environmental History Honouring Jane Carruthers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program of Exhibitions, and Architecture, in Collaboration with the Irwin S

ABOUT CLOSED WORLDS: STOREFRONT ENCOUNTERS THAT NEVER HAPPENED Storefront for Art and Architecture is committed to the advancement of innovative and critical positions at the intersection of architecture, art, Organized by Lydia Kallipoliti and Storefront for Art and design. Storefront’s program of exhibitions, and Architecture, in collaboration with The Irwin S. events, competitions, publications, and projects Chanin School of Architecture of The Cooper Union. provides an alternative platform for dialogue and collaboration across disciplinary, geographic and CLOSED WORLDS EXHIBITION ideological boundaries. Through physical and digital Curator and Principal Researcher: platforms, Storefront provides an open forum for Lydia Kallipoliti experiments that impact the understanding and Research: future of cities, urban territories, and public life. Alyssa Goraieb, Hamza Hasan, Tiffany Montanez, Since its founding in 1982, Storefront has presented Catherine Walker, Royd Zhang, Miguel Lantigua-Inoa, the work of over one thousand architects and artists. Emily Estes, Danielle Griffo and Chendru Starkloff Graphic Design and Exhibition Design: Storefront is a membership organization. If you would Pentagram / Natasha Jen like more information on our membership program with JangHyun Han and Melodie Yashar and benefits, please visit www.storefrontnews.org/ Feedback Drawings: membership. Tope Olujobi Lexicon Editor: For more information about upcoming events and Hamza Hasan projects, or to learn about ways to get involved with Special Thanks: Storefront, -

Carnivora from the Late Miocene Love Bone Bed of Florida

Bull. Fla. Mus. Nat. Hist. (2005) 45(4): 413-434 413 CARNIVORA FROM THE LATE MIOCENE LOVE BONE BED OF FLORIDA Jon A. Baskin1 Eleven genera and twelve species of Carnivora are known from the late Miocene Love Bone Bed Local Fauna, Alachua County, Florida. Taxa from there described in detail for the first time include the canid cf. Urocyon sp., the hemicyonine ursid cf. Plithocyon sp., and the mustelids Leptarctus webbi n. sp., Hoplictis sp., and ?Sthenictis near ?S. lacota. Postcrania of the nimravid Barbourofelis indicate that it had a subdigitigrade posture and most likely stalked and ambushed its prey in dense cover. The postcranial morphology of Nimravides (Felidae) is most similar to the jaguar, Panthera onca. The carnivorans strongly support a latest Clarendonian age assignment for the Love Bone Bed. Although the Love Bone Bed local fauna does show some evidence of endemism at the species level, it demonstrates that by the late Clarendonian, Florida had become part of the Clarendonian chronofauna of the midcontinent, in contrast to the higher endemism present in the early Miocene and in the later Miocene and Pliocene of Florida. Key Words: Carnivora; Miocene; Clarendonian; Florida; Love Bone Bed; Leptarctus webbi n. sp. INTRODUCTION can Museum of Natural History, New York; F:AM, Frick The Love Bone Bed Local Fauna, Alachua County, fossil mammal collection, part of the AMNH; UF, Florida Florida, has produced the largest and most diverse late Museum of Natural History, University of Florida. Miocene vertebrate fauna known from eastern North All measurements are in millimeters. The follow- America, including 43 species of mammals (Webb et al. -

The Carnivora (Mammalia) from the Middle Miocene Locality of Gračanica (Bugojno Basin, Gornji Vakuf, Bosnia and Herzegovina)

Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments https://doi.org/10.1007/s12549-018-0353-0 ORIGINAL PAPER The Carnivora (Mammalia) from the middle Miocene locality of Gračanica (Bugojno Basin, Gornji Vakuf, Bosnia and Herzegovina) Katharina Bastl1,2 & Doris Nagel2 & Michael Morlo3 & Ursula B. Göhlich4 Received: 23 March 2018 /Revised: 4 June 2018 /Accepted: 18 September 2018 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract The Carnivora (Mammalia) yielded in the coal mine Gračanica in Bosnia and Herzegovina are composed of the caniform families Amphicyonidae (Amphicyon giganteus), Ursidae (Hemicyon goeriachensis, Ursavus brevirhinus) and Mustelidae (indet.) and the feliform family Percrocutidae (Percrocuta miocenica). The site is of middle Miocene age and the biostratigraphical interpretation based on molluscs indicates Langhium, correlating Mammal Zone MN 5. The carnivore faunal assemblage suggests a possible assignement to MN 6 defined by the late occurrence of A. giganteus and the early occurrence of H. goeriachensis and P. miocenica. Despite the scarcity of remains belonging to the order Carnivora, the fossils suggest a diverse fauna including omnivores, mesocarnivores and hypercarnivores of a meat/bone diet as well as Carnivora of small (Mustelidae indet.) to large size (A. giganteus). Faunal similarities can be found with Prebreza (Serbia), Mordoğan, Çandır, Paşalar and Inönü (all Turkey), which are of comparable age. The absence of Felidae is worthy of remark, but could be explained by the general scarcity of carnivoran fossils. Gračanica records the most eastern European occurrence of H. goeriachensis and the first occurrence of A. giganteus outside central Europe except for Namibia (Africa). The Gračanica Carnivora fauna is mostly composed of European elements. Keywords Amphicyon . Hemicyon . -

2017 Magdalen College Record

Magdalen College Record Magdalen College Record 2017 2017 Conference Facilities at Magdalen¢ We are delighted that many members come back to Magdalen for their wedding (exclusive to members), celebration dinner or to hold a conference. We play host to associations and organizations as well as commercial conferences, whilst also accommodating summer schools. The Grove Auditorium seats 160 and has full (HD) projection fa- cilities, and events are supported by our audio-visual technician. We also cater for a similar number in Hall for meals and special banquets. The New Room is available throughout the year for private dining for The cover photograph a minimum of 20, and maximum of 44. was taken by Marcin Sliwa Catherine Hughes or Penny Johnson would be pleased to discuss your requirements, available dates and charges. Please contact the Conference and Accommodation Office at [email protected] Further information is also available at www.magd.ox.ac.uk/conferences For general enquiries on Alumni Events, please contact the Devel- opment Office at [email protected] Magdalen College Record 2017 he Magdalen College Record is published annually, and is circu- Tlated to all members of the College, past and present. If your contact details have changed, please let us know either by writ- ing to the Development Office, Magdalen College, Oxford, OX1 4AU, or by emailing [email protected] General correspondence concerning the Record should be sent to the Editor, Magdalen College Record, Magdalen College, Ox- ford, OX1 4AU, or, preferably, by email to [email protected]. -

Wiszniowska T Autor Structure.Pdf

MORPHOLOGY AND SY S TE M ATIC S OF FO ss IL VERTEBRATE S I II Morphology and Systematics of Fossil Vertebrates Edited by Dariusz Nowakowski DN Publisher Wrocław - Poland 2010 III Morphology and Systematics of Fossil Vertebrates Edited by Dariusz Nowakowski Krzysztof Borysławski, Stanislav Čermak, Michał Ginter, Michael Hansen, Piotr Jadwiszczak, Katarzyna Anna Lech, Paweł Mackiewicz, Adam Nadachowski, Robert Niedźwiedzki, Dariusz Nowakowski, Anthony J. Olejniczak, Tomasz Płoszaj, Leonid Rekovets, Piotr Skrzycki, Dawid Surmik, Paweł Socha, Krzysztof Stefaniak, Jacek Tomczyk, Zuzanna Wawrzyniak, Teresa Wiszniowska, Henryk W. Witas Reviewers: Alexander Averianov (Russia) Paweł Bergman (Poland) Nina G. Bogutskaya (Russia) Ivan Horáček (Czech Republic) Grzegorz Kopij (Poland) Barbara Kosowska (Poland) Lutz Maul (Germany) Kenshu Shimada (USA) ©DN Publisher Wrocław - Poland ISBN 987-83-928020-1-3 First edition Circulation 150 copies 2010 IV Contents Preface 1 An application of computed tomography in studies of human remains (for example Egyptian mummy) 3 The Late Miocene and Pliocene Ochotoninae (Lagomorpha, Mammalia) of Europe – the present state of knowledge 9 Teeth of the cladodont shark Denaea from the Carboniferous of central 29 North America New data on the appendicular skeleton and diversity of Eocene Antarctic penguins 45 Reconstruction of forelimb movement of Cyclotosaurus intermedius Sulej et Majer, 2005 from Late Triassic of Poland 52 Analysis of dental enamel thickness in bears with special attention to Ursus spelaeus and U. wenzensis -

History, Status and Distribution of Andalusian Buttonquail in the WP

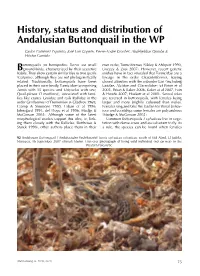

History, status and distribution of Andalusian Buttonquail in the WP Carlos Gutiérrez Expósito, José Luis Copete, Pierre-André Crochet, Abdeljebbar Qninba & Héctor Garrido uttonquails (or hemipodes) Turnix are small own order, Turniciformes (Sibley & Ahlquist 1990, Bground-birds, characterized by their secretive Livezey & Zusi 2007). However, recent genetic habits. They show certain similarities to true quails studies have in fact revealed that Turnicidae are a (Coturnix), although they are not phylogenetically lineage in the order Charadriiformes, having related. Traditionally, buttonquails have been closest affinities with the suborder Lari (including placed in their own family, Turnicidae (comprising Laridae, Alcidae and Glareolidae) (cf Paton et al Turnix with 15 species and Ortyxelos with one, 2003, Paton & Baker 2006, Baker at al 2007, Fain Quail-plover O meiffrenii), associated with fami- & Houde 2007, Hackett et al 2008). Sexual roles lies like cranes Gruidae and rails Rallidae in the are reversed in buttonquails, with females being order Gruiformes (cf Dementiev & Gladkov 1969, larger and more brightly coloured than males. Cramp & Simmons 1980, Urban et al 1986, Females sing and take the lead in territorial behav- Johnsgard 1991, del Hoyo et al 1996, Madge & iour and courtship; some females are polyandrous McGowan 2002). Although some of the latest (Madge & McGowan 2002). morphological studies support this idea, ie, link- Common Buttonquails T sylvaticus live in vege- ing them closely with the Rallidae (Rotthowe & tation with dense cover and are reluctant to fly. As Starck 1998), other authors place them in their a rule, the species can be found when females 92 Andalusian Buttonquail / Andalusische Vechtkwartel Turnix sylvaticus sylvaticus, south of Sidi Abed, El Jadida, Morocco, 16 September 2007 (Benoît Maire). -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

UNDERSTANDING CARNIVORAN ECOMORPHOLOGY THROUGH DEEP TIME, WITH A CASE STUDY DURING THE CAT-GAP OF FLORIDA By SHARON ELIZABETH HOLTE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 Sharon Elizabeth Holte To Dr. Larry, thank you ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my family for encouraging me to pursue my interests. They have always believed in me and never doubted that I would reach my goals. I am eternally grateful to my mentors, Dr. Jim Mead and the late Dr. Larry Agenbroad, who have shaped me as a paleontologist and have provided me to the strength and knowledge to continue to grow as a scientist. I would like to thank my colleagues from the Florida Museum of Natural History who provided insight and open discussion on my research. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Aldo Rincon for his help in researching procyonids. I am so grateful to Dr. Anne-Claire Fabre; without her understanding of R and knowledge of 3D morphometrics this project would have been an immense struggle. I would also to thank Rachel Short for the late-night work sessions and discussions. I am extremely grateful to my advisor Dr. David Steadman for his comments, feedback, and guidance through my time here at the University of Florida. I also thank my committee, Dr. Bruce MacFadden, Dr. Jon Bloch, Dr. Elizabeth Screaton, for their feedback and encouragement. I am grateful to the geosciences department at East Tennessee State University, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard for the loans of specimens. -

Life of Frederick Courtenay Selous, D.S.O. Capt

LIFE OF FREDERICK COURTENAY SELOUS, D.S.O. CAPT. 25TH ROYAL FUSILIERS Chapter XI - XV BY J. G. MILLAIS, F.Z.S. CHAPTER XI 1906-1907 In April, 1906, Selous went all the way to Bosnia just to take the nest and eggs of the Nutcracker, and those who are not naturalists can scarcely understand such excessive enthusiasm. This little piece of wandering, however, seemed only an incentive to further restlessness, which he himself admits, and he was off again on July 12th to Western America for another hunt in the forests, this time on the South Fork of the MacMillan river. On August 5th he started from Whitehorse on the Yukon on his long canoe-journey down the river, for he wished to save the expense of taking the steamer to the mouth of the Pelly. He was accompanied by Charles Coghlan, who had been with him the previous year, and Roderick Thomas, a hard-bitten old traveller of the North- West. Selous found no difficulty in shooting the rapids on the Yukon, and had a pleasant trip in fine weather to Fort Selkirk, where he entered the Pelly on August 9th. Here he was lucky enough to kill a cow moose, and thus had an abundance of meat to take him on the long up-stream journey to the MacMillan mountains, which could only be effected by poling and towing. On August 18th he killed a lynx. At last, on August 28th, he reached a point on the South Fork of the MacMillan, where it became necessary to leave the canoe and pack provisions and outfit up to timber-line. -

Colonial Wildlife Conservation and the Origins of the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire (1903–1914)

Oryx Vol 37 No 2 April 2003 Colonial wildlife conservation and the origins of the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire (1903–1914) David K. Prendergast and William M. Adams Abstract Fauna & Flora International (FFI) celebrates The SPWFE drew together an elite group of colonial its centenary in 2003. It was founded as the Society administrators, hunters and other experts on game in for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire Africa, and was eCective in lobbying the Colonial OBce (SPWFE) in London in 1903. This paper analyses the about preservation. Many of its concerns, and ideas events, people, and debates behind its formation and about how to address them, are similar to those that are early development. It discusses why the Society was current today, a century after its establishment. formed, how it worked, and what its main concerns were. It considers the nature and success of the Society’s Keywords Colonial conservation, colonial policy, con- work from 1903 to 1914 in influencing the British servation history, Fauna & Flora International, game Colonial OBce’s policy on issues such as game reserves, reserves, hunting, preservation. hunting and wildlife clearance for tsetse control in Africa. became linked to beliefs about links between climate Introduction change and drought, and led to the establishment of Fauna & Flora International (FFI) celebrates its centenary measures for forest protection (Grove, 1992, 1995, 1997, in 2003, claiming to be the world’s oldest international 1998). Imperial forestry, including ideas of rational conservation organization. It was founded as the Society resource use, was well established in India by the mid- for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire nineteenth century (Barton, 2002), as well as in the South (SPWFE, hereafter the Society) in 1903. -

Intercontinental Migration of Large Mammalian Carnivores: Earliest Occurrence of the Old World Beardog Amphicyon (Carnivora, Amphicyonidae) in North America Robert M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of 2003 Intercontinental Migration of Large Mammalian Carnivores: Earliest Occurrence of the Old World Beardog Amphicyon (Carnivora, Amphicyonidae) in North America Robert M. Hunt Jr. University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Hunt, Robert M. Jr., "Intercontinental Migration of Large Mammalian Carnivores: Earliest Occurrence of the Old World Beardog Amphicyon (Carnivora, Amphicyonidae) in North America" (2003). Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. 545. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub/545 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Chapter 4 Intercontinental Migration of Large Mammalian Carnivores: Earliest Occurrence of the Old World Beardog Amphicyon (Carnivora, Amphicyonidae) in North America ROBERT M. HUNT, JR.1 ABSTRACT North American amphicyonid carnivorans are prominent members of the mid-Cenozoic terres- trial carnivore community during the late Eocene to late Miocene (Duchesnean to Clarendonian). Species range in size from ,5kgto.200 kg. Among the largest amphicyonids are Old and New World species of the genus Amphicyon: A. giganteus in Europe (18±;15? Ma) and Africa, A. ingens in North America (15.9±;14.2 Ma). Amphicyon ®rst appears in the Oligocene of western Europe, surviving there until the late Miocene. -

The Edges of Environmental History Honouring Jane Carruthers

Perspectives The Edges of Environmental History Honouring Jane Carruthers Edited by CHRISTOF MAUCH LIBBY ROBIN 2014 / 1 RCC Perspectives The Edges of Environmental History Honouring Jane Carruthers Edited by Christof Mauch Libby Robin 2014 / 1 2 RCC Perspectives Contents Prologue 5 Jane Carruthers and International Environmental History Christof Mauch and Libby Robin 9 Environmental History with an African Edge Jane Carruthers Part 1: Thinking with Animals 19 How Wild is Wild? Harriet Ritvo 25 Thinking with Birds Tom Dunlap 31 Animal Pasts, Humanised Futures: Living with Big Wild Animals in an Emerging Economy Mahesh Rangarajan Interlude 37 The Beast of the Forest Tom Griffiths Part 2: Inside and Out Wildlife Reserves 47 National Parks as Cosmopolitics Bernhard Gißibl 53 Seeing the National Park from Outside It: On an African Epistemology of Nature Clapperton Mavhunga 61 On Being Edgy: The Potential of Parklands and Justice in the Global South Emily Wakild 3 Interlude 69 Mandy Martin’s Artistic Explorations Jane Carruthers Part 3: Knowing Nature 75 Bio-invasions, Biodiversity, and Biocultural Diversity: Some Problems with These Concepts for Historians William Beinart 81 The Biopolitics of the Border Etienne Benson 87 Adventures in Gondwana: Science in the South Saul Dubow 93 Biography and Scientific Endeavour Libby Robin Interlude 101 How to Read a Bridge Rob Nixon Part 4: Environmental Injustice and the Promise of History 113 Constructing and De-constructing Communities: Tales of Urban Injustice and Resistance in Brazil and South Africa Lise Sedrez 117 Dangerous Territory: The Contested Space Between Conservation and Justice Bron Taylor 123 History and Audacity: Talking to Conservation Science Catherine A. -

(Chiroptera: Natalidae) from the Early Miocene of Florida, with Comments on Natalid Phylogeny

Journal of Mammalogy, 84(2):729±752, 2003 A NEW BAT (CHIROPTERA: NATALIDAE) FROM THE EARLY MIOCENE OF FLORIDA, WITH COMMENTS ON NATALID PHYLOGENY GARY S. MORGAN* AND NICHOLAS J. CZAPLEWSKI New Mexico Museum of Natural History, 1801 Mountain Road NW, Albuquerque, NM 87104, USA (GSM) Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article/84/2/729/2373805 by guest on 29 September 2021 Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73072, USA (NJC) We describe a new extinct genus and species of bat belonging to the endemic Neotropical family Natalidae (Chiroptera) from the Thomas Farm Local Fauna in northern peninsular Florida of early Miocene age (18±19 million years old). The natalid sample from Thomas Farm consists of 32 fossils, including a maxillary fragment, periotics, partial dentaries, isolated teeth, humeri, and radii. A proximal radius of an indeterminate natalid is reported from the I-75 Local Fauna of early Oligocene age (about 30 million years old), also from northern Florida. These fossils from paleokarst deposits in Florida represent the 1st Tertiary records of the Natalidae. Other extinct Tertiary genera previously referred to the Natalidae, including Ageina, Chadronycteris, Chamtwaria, Honrovits, and Stehlinia, may belong to the superfamily Nataloidea but do not ®t within our restricted de®nition of this family. Eight derived characters of the Natalidae sensu stricto are discussed, 5 of which are present in the new Miocene genus. Intrafamilial phylogenetic analysis by parsimony of the Natal- idae suggests that the 3 living subgenera, Natalus (including N. major, N. stramineus, and N. tumidirostris), Chilonatalus (including C.