Managing the Remains of Citizen Soldiers HUMAN REMAINS & VIOLENCE by Severe Limitations, Both Technical and Logistical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC De La Brie Champenoise

Communes membres : 0 ortrait P Foncier CC de la Brie Bergères-sous-Montmirail, Boissy-le-Repos, Charleville, Corfélix, Corrobert, Fromentières, Le Gault-Soigny, Janvilliers, Mécringes, Montmirail, Morsains, Rieux, Champenoise Soizy-aux-Bois, Le Thoult-Trosnay, Tréfols, Vauchamps, Verdon, Le Vézier, La Villeneuve-lès-Charleville 0 Direction Régionale de l'environnement, de l'aménagement et du logement GRAND EST SAER / Mission Foncier Novembre 2019 http://www.grand-est.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/ 0 CC de la Brie Champenoise Périmètre Communes membres 01/2019 19 ( Marne : 19) Surface de l'EPCI (km²) 280,04 Dépt Marne Densité (hab/km²) en 2016 EPCI 27 Poids dans la ZE Épernay*(100%) ZE 47 Pop EPCI dans la ZE Épernay(6,9%) Grand Est 96 * ZE de comparaison dans le portrait Population 2011 7 491 2016 7 441 Évolution 2006 - 2011 75 hab/an Évolution 2011 - 2016 -10 hab/an 10 communes les plus peuplées (2016) Montmirail 3 611 48,5% Le Gault-Soigny 540 7,3% 0 Fromentières 375 5,0% Vauchamps 356 4,8% Charleville 244 3,3% Boissy-le-Repos 222 3,0% Verdon 211 2,8% Corrobert 203 2,7% Rieux 200 2,7% Mécringes 199 2,7% Données de cadrage Évolution de la population CC de la BrieCC de la Champenoise Evolution de la population depuis 1968 Composante de l'évolution de la population en base 100 en 1962 de 2011 à 2016 (%) 140 2% 1,7% 1,1% 120 1% 0,8% 0,3% 0,0% 100 0% 0,0% -1% -0,7%-0,6% 80 -0,9% -0,8% -2% -1,5% -1,5% 60 1968 1975 1982 1990 1999 2006 2011 2016 EPCI ZE Département Grand Est Région Département ZE EPCI Evolution totale Part du solde naturel Part -

Archives Départementales De La Marne 2020 Commune Actuelle

Archives départementales de la Marne 2020 Commune actuelle Commune fusionnée et variante toponymique Hameau dépendant Observation changement de nom Ablancourt Amblancourt Saint-Martin-d'Ablois Ablois Saint-Martin-d'Amblois, Ablois-Saint-Martin Par décret du 13/10/1952, Ablois devient Saint-Martin d'Ablois Aigny Allemanche-Launay-et-Soyer Allemanche-Launay Allemanche et Launay Par décret du 26 septembre 1846, Allemanche-Launay absorbe Soyer et prend le nom d'Allemanche-Launay-et- Soyer Allemanche-Launay-et-Soyer Soyer Par décret du 26 septembre 1846, Allemanche-Launay absorbe Soyer et prend le nom d'Allemanche-Launay-et- Soyer Allemant Alliancelles Ambonnay Par arrêté du 12/12/2005 Ambonnay dépend de l'arrondissement d'Epernay Ambrières Ambrières et Hautefontaine Par arrêté du 17/12/1965, modification des limites territoriales et échange de parcelles entre la commune d'Ambrières et celle de Laneuville-au-Pont (Haute-Marne) Anglure Angluzelles-et-Courcelles Angluzelle, Courcelles et Angluselle Anthenay Aougny Ogny Arcis-le-Ponsart Argers Arrigny Par décrets des 11/05/1883 et 03/11/1883 Arrigny annexe des portions de territoire de la commune de Larzicourt Arzillières-Neuville Arzillières Par arrêté préfectoral du 05/06/1973, Arzillières annexe Neuville-sous-Arzillières sous le nom de Arzillières-Neuville Arzillières-Neuville Neuville-sous-Arzillières Par arrêté préfectoral du 05/06/1973, Arzillières annexe Neuville-sous-Arzillières sous le nom de Arzillières-Neuville Athis Aubérive Aubilly Aulnay-l'Aître Aulnay-sur-Marne Auménancourt Auménancourt-le-Grand Par arrêté du 22/11/1966, Auménancourt-le-Grand absorbe Auménancourt-le-Petit et prend le nom d'Auménancourt Auménancourt Auménancourt-le-Petit Par arrêté du 22/11/1966, Auménancourt-le-Grand absorbe Auménancourt-le-Petit et prend le nom d'Auménancourt Auve Avenay-Val-d'Or Avenay Par décret du 28/05/1951, Avenay prend le nom d'Avenay- Val-d'Or. -

LE PARTENARIAT AVEC LES COLLECTIVITÉS ANNÉE 2020 Dispositions Applicables À Compter Du Er1 Janvier 2020 Pour Un PARTENARIAT Avec Les COLLECTIVITÉS

LE PARTENARIAT AVEC LES COLLECTIVITÉS ANNÉE 2020 Dispositions applicables à compter du 1er janvier 2020 Pour un PARTENARIAT avec les COLLECTIVITÉS La loi NOTRé du 7 août 2015 a confirmé le rôle du Département de solidarité et de cohésion territoriale. Cette responsabilité s’exerce au travers des investissements propres de la collectivité départementale (voirie, collèges, aménagement numérique, réseau vélos et voies vertes...) mais également dans le soutien qu’elle apporte aux projets d’investissement des communes et EPCI. Sur ce dernier point il revient à chaque Département de définir les modalités et le niveau de ce soutien. La Marne a fait de cette politique un axe fort et permanent de son intervention sur son territoire : près de 13 M€/an ont ainsi été accordés entre 2011 et 2019 à près de 2 000 opérations portées par les collectivités. Notre dispositif de partenariat avec les collectivités infra-départementales a en effet pour ambition : • d’améliorer le cadre de vie des marnaises et des marnais en soutenant les projets, tant en milieu urbain qu’en milieu rural, favorisant le maintien ou la création de services locaux de proximité de qualité (école primaire, mairie, salle des fêtes, caserne de pompiers, aménagement de voirie,...) ; • et de rendre attractif le territoire en soutenant: - la réhabilitation du patrimoine classé (église, tableaux, statue,..), - la réalisation de projets structurants rendant le département attractif (espace aquatique, musée, salle événementielle, aménagement routier, voie verte,…). Depuis 1982, l’Assemblée départementale a fait évoluer à plusieurs reprises les modalités de soutien aux collectivités tant sur la nature des projets aidés que sur les modalités de calcul de la subvention accordée. -

CC De La Brie Champenoise

CCI Marne en Champagne Analyse économique & Data La Communauté de communes de la Brie Champenoise Son président : Etienne DHUICQ Son siège : Montmirail Sa composition : 19 communes Commune Pop. 2015 Bergères-sous-Montmirail 121 Boissy-le-Repos 226 Charleville 249 Corfélix 111 Corrobert 201 Fromentières 380 Janvilliers 169 La Villeneuve-lès-Charleville 114 Le Gault-Soigny 544 Le Thoult-Trosnay 100 Le Vézier 195 Mécringes 193 Montmirail 3 643 Morsains 129 Rieux 197 Soizy-aux-Bois 179 Tréfols 155 Vauchamps 359 Verdon 209 CCI Marne en Champagne Analyse économique et Data – 1er semestre 2019 Dynamique des entreprises du territoire Données issues du fichier consulaire en janvier 2019 Répartition des établissements et effectifs salariés par secteurs d’activité Etablissements Effectifs (1) 48% 222 établissements 30% (1) dont 34 micro-entrepreneurs 1 393 10% salariés 6% 6% 66% 3% 16% 1% 13% Industrie Construction Commerce CHR* Services *Cafés, Hôtels, Restaurants Principaux employeurs Entreprise Site principal APE Secteur principal Effectifs Nb d’Ets Industrie AXON CABLE Montmirail 2732Z 702 1 manufacturière Industrie MAROQUINERIE MARJO Montmirail 1512Z 150 1 manufacturière CHADON/CARREFOUR Montmirail 4711D Commerce de détail 48 1 MARKET IPC PETROLEUM FRANCE Montmirail 0610Z Industrie extractive 46 1 ETABLISSEMENTS MARCY Montmirail 4632C Commerce de gros 36 1 Transports et REGNAULT AUTOCARS Montmirail 4939A 25 1 entreposage Évolution des créations et radiations d’entreprises sur 5 ans 40 Sur 5 ans : 30 129 20 créations 86 10 radiations Créations Radiations 0 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Les micro-entreprises représentent 50% des créations et 40% des disparitions, début 2019. CCI Marne en Champagne Analyse économique et Data – 1er semestre 2019 Afin de pouvoir comparer les territoires, le périmètre géographique de l’ensemble des données traitées dans ce document a été adapté à celui en vigueur au 01/01/2017 Synthèse des principaux indicateurs (Cf. -

95 Communes Rassemblant Au Total 35 587 Habitants (Selon Données INSEE 2012)

Liste des communes constitutives du GAL Brie et Champagne Le GAL du Pays de Brie et Champagne est constitué de 95 communes rassemblant au total 35 587 habitants (selon données INSEE 2012). Voici la liste des communes qui constituent son périmètre : Nombre N° Nom de la commune d'habitants EPCI INSEE (INSEE 2012) 1 Allemanche-Launay-et-Soyer 51004 106 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 2 Allemant 51005 168 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 3 Anglure 51009 826 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 4 Angluzelles-et-Courcelles 51010 144 CC du Sud Marnais 5 Bagneux 51032 496 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 6 Bannes 51035 282 CC du Sud Marnais 7 Barbonne-Fayel 51036 494 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 8 Baudement 51041 121 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 9 Bergères-sous-Montmirail 51050 131 CC de la Brie Champenoise 10 Bethon 51056 287 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 11 Boissy-le-Repos 51070 201 CC de la Brie Champenoise 12 Bouchy-Saint-Genest 51071 186 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 13 Broussy-le-Grand 51090 312 CC du Sud Marnais 14 Broussy-le-Petit 51091 128 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 15 Broyes 51092 366 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 16 Champguyon 51116 269 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 17 Chantemerle 51124 52 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 18 Charleville 51129 280 CC de la Brie Champenoise 19 Chichey 51151 167 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 20 Châtillon-sur-Morin 51137 187 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 21 Clesles 51155 602 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 22 Conflans-sur-Seine 51162 674 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 23 Connantray-Vaurefroy 51164 180 CC du Sud Marnais 24 Connantre 51165 -

Les Petits Cantons De 1790 Dans La Région De Château-Thierry

- 13 - Les petits cantons de 1790 dans la région de Château-Thierry L’assemblée Constituante a pris une série de mesures favorisant la décentralisation et uniformisant les structures administratives qui étaient fort complexes avant la Révolution. Certaines institutions, comme le département et la commune, subsistent encore. Les cadres intermédiaires ont subi diverses mutations. A titre d’exemple, les uni- tés cantonales initiales ne se maintiennent que pendant une dizaine d’années. La présente étude se propose d’étudier ce type de phéno- mène autour de Château-Thierry. ORIGINES HISTORIQUES De nouvelles circonscriptions administratives sont donc créées au début de l’année 1790. La ville de Château-Thierry, après différentes ébauches de découpages, est incluse dans le département de l’Aisne dont le chef-lieu est Laon (1 & 2). Elle se trouve à la tête d’un district, les cinq autres étant dévolus à Laon, Soissons, Chauny, Vervins et Saint-Quentin. Le département comprend alors 63 cantons, dont 13 composant le district de Château-Thierry ;ce dernier, assez proche de l’arrondissement actuel, peut commodément servir de cadre à notre étude. Dans quelle mesure ce territoire dérive-t-il de structures antérieu- res ? Il correspond approximativement à la pointe méridionale de la généralité de Soissons. Les éléments fixateurs ont été ici constitués par l’élection et le bailliage de Château-Thierry dont les contours sont assez proches (3 & 4). S’y retrouvent les subdélégations de Château- Thierry dans sa quasi-totalité, de Fère-en-Tardenois en entier et 12 communes de celle de Montmirail, mais sans cette ville. Viennent s’y ajouter, provenant de l’élection de Soissons, la frange sud de la subdé- légation d’Oulchy-le-Château, et issues de l’élection de Crépy, la sub- délégation de Neuilly-Saint-Front et les deux communes de Silly-la- Poterie et de la Ferté-Milon. -

ELECTIONS MUNICIPALES 1Er Tour Du 15 Mars 2020

ELECTIONS MUNICIPALES 1er tour du 15 Mars 2020 Livre des candidats par commune (scrutin plurinominal) (limité aux communes du portefeuille : Arrondissement de Épernay) Page 1 Elections Municipales 1er tour du 15 Mars 2020 Candidats au scrutin plurinominal majoritaire Commune : Allemanche-Launay-et-Soyer (Marne) Nombre de sièges à pourvoir : 11 M. ADNOT José M. BEAUVAIS Cyrille M. CARTIER Michel M. CHAINE Eric M. CHAMPION Bernard Georges Paul Mme FAROUX Lara Yvonne Monique M. GIROUX Joël M. GOUHIER François M. HÉRARD Anthony M. MACLIN Alain M. MACLIN Fabien Mme PASQUET Martine Mme THOMINET Laurence Jeannine Madeleine Page 2 Elections Municipales 1er tour du 15 Mars 2020 Candidats au scrutin plurinominal majoritaire Commune : Allemant (Marne) Nombre de sièges à pourvoir : 11 Mme AVELINE Corinne M. DEBUISSON Sébastien M. DELABALLE Thomas M. DELONG Emeric Mme DELONG Marlène Mme DOUCET Carole M. LEPAGE Denis M. PAILLOT Jérémy M. PUISSANT Joël M. REMY Maxence M. STOCKER Francis Page 3 Elections Municipales 1er tour du 15 Mars 2020 Candidats au scrutin plurinominal majoritaire Commune : Ambonnay (Marne) Nombre de sièges à pourvoir : 15 M. CHARPENTIER Thierry Mme COUTIER Nathalie Mme DEMIERE Maud M. DESFOSSE Frédéric Mme HUGUET Sabine M. JANNETTA Ludovic M. MODE Franck Mme MOREAU Françoise Mme PAYELLE Valérie M. PETIT Didier Mme PHILIPPOT Claire M. PONSIN Jean-Guy Mme RODEZ Aurélie M. ROUSSINET Jean-Luc Mme VESSELLE Vanessa Page 4 Elections Municipales 1er tour du 15 Mars 2020 Candidats au scrutin plurinominal majoritaire Commune : Anglure (Marne) Nombre de sièges à pourvoir : 15 M. BASSON Xavier M. BIGOT Daniel Mme BOUCHER Magali M. CARDINAL Daniel M. -

Montmirail Et Son Intercomm Unalité

22 JANVIER 2021 BRIE CHAMPENOISE info Montmirail et son intercommunalité À DÉCEMBRE DE JUILLET 2020 SAPEUR- combien de véhicules de secours aux victimes. Occupé, concentré par mon POMPIER devoir, je n’ai pas eu le temps de les compter mais j’en ai rarement vu autant… VOLONTAIRE Des heures durant, soudés à nos ca- marades Sapeurs de Châlons, Ester- nay, Épernay, Vertus et Sézanne, nous le combattons. L’objectif à atteindre ? RÉCIT D’UNE Limiter les dégâts et empêcher sa pro- pagation, le centre-ville de Montmirail INTERVENTION est historique, tous les immeubles ne 14 juillet 2020, minuit a déjà sonné. font qu’un. Comme tout le monde à la maison, je Des heures durant, nous nous relayons dors. pour combattre le brasier. Mon bip se déclenche, les yeux intervention du 14 juillet 2020 place L’horloge affiche 13h ce 15 juillet pleins de sommeil, je l’attrape et le Rémy Petit à Montmirail 2020. Après plus de 12 heures sans coupe avant que mes enfants ne se répit, le feu est noyé, l’incendie est réveillent. pas sa place, nous nous équipons, éteint. Les immeubles sont sécurisés, Mon écran affiche : « place Rémy Petit casqués, masqués. Je descends avec enfin...!!! enfin...!!! C’est toute la à Montmirail » et une mission : « IN- mon appareil respiratoire sur le dos. victoire d’un corps. CENDIE D’HABITATION ». Tout se met en place, chacun a sa Nous voilà de retour à la caserne mais Le réveil est total, l’adrénaline est là ! mission, le matériel est déployé et l’intervention n’est pas encore ache- Le rythme cardiaque s’accélère à la déjà nous progressons. -

Compétences Marne

Communes du departement de la Marne en A Ablancourt Aigny Allemanche-Launay-et-Soyer Allemant Alliancelles Ambonnay Ambrières Anglure Angluzelles-et-Courcelles Anthenay Aougny Arcis-le-Ponsart Argers Arrigny Arzillières-Neuville Athis Aubérive Aubilly Aulnay-l'Aître Aulnay-sur-Marne Auménancourt Auve Avenay-Val-d'Or Avize Ay Communes du departement de la Marne en B Baconnes Bagneux Bannay Bannes Barbonne-Fayel Baslieux-lès-Fismes Baslieux-sous-Châtillon Bassu Bassuet Baudement Baye Bazancourt Beaumont-sur-Vesle Beaunay Beine-Nauroy Belval-en-Argonne Belval-sous-Châtillon Bergères-lès-Vertus Bergères-sous-Montmirail Berméricourt Berru Berzieux Bétheniville Bétheny Bethon Bettancourt-la-Longue Bezannes Bignicourt-sur-Marne Bignicourt-sur-Saulx Billy-le-Grand Binarville Binson-et-Orquigny Bisseuil Blacy Blaise-sous-Arzillières Blesme Bligny Boissy-le-Repos Bouchy-Saint-Genest Bouilly Bouleuse Boult-sur-Suippe Bourgogne Boursault Bouvancourt Bouy Bouzy Brandonvillers Branscourt Braux-Saint-Remy Braux-Sainte-Cohière Bréban Breuil Breuvery-sur-Coole Brimont Brouillet Broussy-le-Grand Broussy-le-Petit Broyes Brugny-Vaudancourt Brusson Bussy-le-Château Bussy-le-Repos Bussy-Lettrée Communes du departement de la Marne en C Caurel Cauroy-lès-Hermonville Cernay-en-Dormois Cernay-lès-Reims Cernon Chaintrix-Bierges Châlons-en-Champagne Châlons-sur-Vesle Chaltrait Chambrecy Chamery Champaubert Champfleury Champguyon Champigneul-Champagne Champigny Champillon Champlat-et-Boujacourt Champvoisy Changy Chantemerle Chapelaine Charleville Charmont Châtelraould-Saint-Louvent -

Les Cartes Des Sections Généralistes, Agricoles, Par

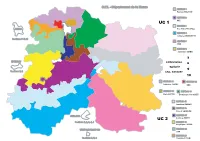

S.I.T. - Département de la Marne SECTION 1 Patricia MOUTON SECTION 2 XXX SECTION 3 REIMS Eric PHILIPPOTEAU SECTION 4 A.Marie ANDRUETTE Sections 11 à 20 SECTION 5 XXX SECTION 6 Catherine IDENN EPERNAY Sections 1, 2 SECTION 11 SECTION 12 Catherine CHERY XXX SECTION 13 SECTION 14 Alain EATON Dominique JACQUIER SECTION 15 Jonathan EMOND SECTION 16 Pascal SENEUZE CHALONS SECTION 17 Anthony SMITH Sections 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 SECTION 18 Angélique CORNU VITRY LE FRANCOIS SECTION 19 XXX SECTION 20 Sections 6, 5, 9 Ouarda ZITOUNI S.I.T. - Département de la Marne sections à compétence agricole SECTION 7 Julien WOELFFLE SECTION 8 Sylvain SKURAS SECTION 9 XXX SECTION 10 Audrey PIERRE S.I.T. - Département de la Marne UC 1 SECTION 1 Patricia MOUGIN SECTION 2 Jean-Pierre TINE SECTION 3 Eric PHILIPPOTEAU SECTION 4 A.Marie ANDRUETTE SECTION 5 XXX SECTION 6 Catherine IDENN CHALONS Sections 4 et 5 : Sections 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 compétence transport sur toute l'UC Section 4 : compétence transport aérien sur toute l'UC VITRY LE FRANCOIS Sections 6, 5, 9 S.I.T. - Département de la Marne SECTION 11 UC 2 Catherine CHERY SECTION 12 XXX SECTION 13 Alain EATON REIMS SECTION 14 Dominique JACQUIER SECTION 15 Sections 11 à 20 Jonathan EMOND SECTION 16 Pascal SENEUZE SECTION 17 Anthony SMITH SECTION 18 Angélique CORNU SECTION 19 XXX SECTION 20 Ouarda ZITOUNI EPERNAY Sections 12 et 13 : compétence transport Sections 1, 2 sur toute l'UC Section 13 : compétence transport aérien sur toute l'UC Section 17 : compétence transport ferroviaire sur tout le département Section 19 : compétence -

Liste Des Maires 2014

NOM DE LA COMMUNE CP NOM PRENOM Arrt ABLANCOURT 51240 M. BREUZARD Steve Vitry-le- François AIGNY 51150 Mme NICLET Chantal Châlons-en- Champagne ALLEMANCHE-LAUNAY-ET-SOYER 51260 M. CHAMPION Bernard Epernay ALLEMANT 51120 Mme DOUCET Carole Epernay ALLIANCELLES 51250 M. GARCIA DELGADO Jean-Jacques Vitry-le- François AMBONNAY 51150 M. RODEZ Eric Epernay AMBRIERES 51290 M. DROIN Denis Vitry-le- François ANGLURE 51260 M. ESPINASSE Frédéric Epernay ANGLUZELLES-ET-COURCELLES 51230 M. COURJAN Jean-François Epernay ANTHENAY 51700 Mme BERNIER Claudine Reims AOUGNY 51170 M. LEQUART Alain Reims ARCIS-LE-PONSART 51170 M. DUBOIS Jean-Luc Reims ARGERS 51800 M. SCHELFHOUT Gilles Sainte- Menehould ARRIGNY 51290 Mme BOUQUET Marie-France Vitry-le- François ARZILLIERES-NEUVILLE 51290 M. CAPPE Michel Vitry-le- François ATHIS 51150 M. EVRARD Jean-Loup Châlons-en- Champagne AUBERIVE 51600 M. LORIN Pascal Reims AUBILLY 51170 M. LEROY Jean-Yves Reims AULNAY-L'AITRE 51240 M. LONCLAS Michel Vitry-le- François AULNAY-SUR-MARNE 51150 M. DESGROUAS Philippe Châlons-en- Champagne AUMENANCOURT 51110 M. GUREGHIAN Franck Reims AUVE 51800 M. SIMON Claude Sainte- Menehould AVENAY-VAL-D'OR 51160 M. MAUSSIRE Philippe Epernay AVIZE 51190 M. DULION Gilles Epernay AY CHAMPAGNE 51160 M. LEVEQUE Dominique Epernay BACONNES 51400 M. GIRARDIN Francis Reims BAGNEUX 51260 M. GOUILLY Guy Epernay BAIZIL 51270 Mme METEYER Christine Epernay BANNAY 51270 Mme CURFS Muguette Epernay BANNES 51230 M. GUILLAUME Patrick Epernay BARBONNE-FAYEL 51120 M. BENOIST Jean-Louis Epernay BASLIEUX-LES-FISMES 51170 M. FRANCOIS Jacky Reims BASLIEUX-SOUS-CHATILLON 51700 M. GUILLEMONT Jean-Marc Reims BASSU 51300 Mme LE GUINIO SQUELART Laurence Vitry-le- François BASSUET 51300 Mme GANSTER Carole Vitry-le- François BAUDEMENT 51260 Mme BERTHIER Danielle Epernay BAYE 51270 M. -

Son Excellence Monsieur Laurent FABIUS Ministre Des Affaires Étrangères Et Du Développement International 37, Quai D'orsay F - 75351 – PARIS

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 07.05.2014 C(2014) 2609 final PUBLIC VERSION This document is made available for information purposes only. SUBJECT: STATE AID SA.38182 (2014/N) – FRANCE REGIONAL AID MAP 2014-2020 Sir, 1. PROCEDURE (1) On 28 June 2013 the Commission adopted the Guidelines on Regional State Aid for 2014-20201 (hereinafter "RAG"). Pursuant to paragraph 178 of the RAG, each Member State should notify to the Commission, following the procedure of Article 108(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, a single regional aid map applicable from 1 July 2014 to 31 December 2020. In accordance with paragraph 179 of the RAG, the approved regional aid map is to be published in the Official Journal of the European Union, and will constitute an integral part of the RAG. (2) By letter dated 16 January 2014, registered at the Commission on 16 January 2014 (2014/004765), the French authorities duly notified a proposal for the regional aid map of France for the period from 1 July 2014 to 31 December 2020. (3) On 14 February 2014 the Commission requested additional information (2014/016613), which was provided by the French authorities on 11 March 2014 (2014/027539), on 25 March 2014 (2014/033926) and on 2 April 2014 (2014/037495). 1 OJ C 209, 23.07.2013, p.1 Son Excellence Monsieur Laurent FABIUS Ministre des Affaires étrangères et du Développement international 37, Quai d'Orsay F - 75351 – PARIS Commission européenne, B-1049 Bruxelles/Europese Commissie, B-1049 Brussel – Belgium Telephone: 00- 32 (0) 2 299.11.11.