John Lunt and the Lancashire Plot, 1694

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bus Timetable This Service Is Provided by Arriva

Valid from 11 April 2021 Bus timetable 63 Bootle - Fazakerley - Bootle This service is provided by Arriva BOOTLE Bus Station North Park SEAFORTH Crosby Road South WATERLOO Crosby Road North CROSBY Crosby Village Brownmoor Lane NETHERTON Magdelene Square AINTREE Park Lane FAZAKERLEY Aintree University Hospital www.merseytravel.gov.uk What’s changed? Some times are changed. Any comments about this service? If you’ve got any comments or suggestions about the services shown in this timetable, please contact the bus company who runs the service: Arriva North West 73 Ormskirk Road, Aintree, Liverpool, L9 5AE 0344 800 44 11 If you have left something in a bus station, please contact us at Merseytravel: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 0151 330 1000 In writing PO Box 1976, Liverpool, L69 3HN Need some help or more information? For help planning your journey, call 0151 330 1000, open 0800 - 2000, 7 days a week. You can visit one of our Travel Centres across the Merseytravel network to get information about all public transport services. To find out opening times, phone us on 0151 330 1000. Our website contains lots of information about public transport across Merseyside. You can visit our website at www.merseytravel.gov.uk Bus services may run to different timetables during bank and public holidays, so please check your travel plans in advance. Large print timetables We can supply this timetable in another format, such as large print. Either call 0151 330 1000 or email us at [email protected] 8 63 Bootle - Fazakerley - Bootle Arriva -

ALTCAR Training Camp

ALTCAR TraINING CAMP A unique wildlife habitat on the Sefton Coast I I I I I I I I I I I Cabin Hill I I I I Formby I I I Dry Training Area I I Alt Grange I I Altcar Training Camp I Altcar Training Camp North Lookout I I River Alt I I R i v I e I r A I l t I I I Pumping I Station I I Lookout I I Hightown I Range Control I I I I Ranges I I I Boat Yard Danger Area I I I I I I South Lookout I I I I I I I I I Crosby I I FOREWORD Altcar Training Camp is owned and managed by the unique habitats. As part of this coast Altcar is a genuine Reserve Forces and Cadets Association for the North sanctuary for nature, the foreshore danger area giving West of England and the Isle of Man as one of the UK’s protection to thousands of passage and over-wintering premier facilities for small arms marksmanship training. birds, the dunes a home to internationally protected species such as the Sand Lizard and Natterjack Toad and In any year over thirty five thousand soldiers learn their the more recent woodland plantations harbouring the rifle skills at Altcar before being deployed to military nationally rare Red Squirrel. activity throughout the world. Since 1977, a Conservation Advisory Group has Altcar Training Camp is also part of the Sefton Coast, supported the management of the Altcar estate, giving a wild stretch of beaches, dunes and woodlands lying advice to ensure that nature conservation sits alongside between Liverpool and Southport. -

653 Sefton Parish

SEFTO:N. 653 Kirby Rbt., blacksmith Charnock John, and farrier Martin J ames, beer house Cropper Thos., Park house Phillips Mr. David, Melling cottage Cross Edward, Old Parsonage nimmer Wm., nct. & farmer, White Lion Edwards Thos., Tomlinson's farm Stock Mr. Jdm, Cunscough Gregson John Sumner Wm., vict. and farmer, Hen and Gregson Wm. Chickens, Cunscough Hulme Humphrey, New house Tyrer Henry, gent., Waddicre house Hulme Jas., Carr house Willcock Geo., quarry master Huyton Thos. Ledson Daniel, Clayton's farm FAmmRS. Ledson Henry, Spencer's farm Barnes Edward, Hall wood farm Ledson Wm., MeIling house Barnes Jas., Barnes' farm Lyon James Barnes John, Hall wood farm Moorcroft Wm., Largis-house, Cunscough Barms Thos" Uoorfield house Pinnington Thos., Lyon's farm Bell John, Old bouse croft Rawlinson Rbt., The Meadows Bennett George Rushton IsabeIla Bullen David Smith William Bullen Rbt., Bank hall Taylor James Bushell John, Cunscough hall Webster Ralphl Bradley's farm SEFTON PARISH. This parish is bounded on the west by the Irish sea and the mouth of the M~rsey; Of} the north and north-east. by the parish of Halsall; and on the #:\outh /lnd south-west by the parish ofWalton. Though not a veryeJftensive parish, being only seven miles in length and four in breadth, it comprises the ten townships of Sefton, Aintree, Great Crasby, Little Crosby, Ince Blundell, Litherland, Lunt, N etherton, Orrell and Ford, and Thorn ton. The river Alt, which is formed by numerous rills issuing from Fazakerley, Croxteth, Simonswood, and Kirkby, flows by Aintree. Lunt, apd Ince Blundell, on its way to the Irish sea. -

133 Times.Qxd

133 Kirkby - Waterloo serving: Southport Kirkby Formby Melling Maghull Crosby Maghull Lunt Kirkby Rainford West Wallasey Kirby Bootle West Birkenhead Derby St Helens Crosby Liverpool Prescot Huyton Newton -le- Waterloo Heswall Willows Bromborough Garston Halewood Speke Timetable valid from 08 October 2012 Route 133 is operated by: Changes contained in this edition: The service is now operated by Cumfybus, without subsidy from Merseytravel. The route and the times are unchanged. NTED O RI N P R E R C E Y P C LE D PA www.merseytravel.gov.uk DEL 100912 Route 133: Maghull Northway Waterloo - Kirkby Admin 5 EAS WESTWAY TWAY Deyes Lane Northway E E A N Deyes S A Liverpool T L Lane Road North W N A L E Y UN E T R E RO G N AD LA G ON L Foxhouse 3 Lane ANE TON L Liverpool Thornton Lunt SEF Road South Wood Ince Thornton PO Lane Hall VE Old Racecourse Lane R TY Road L LA S UN N O T E E UT ROA N M58 H D LA LE P S A O E TH RT G E ID R R 4 R B BRID B A OAD GE R S L R A O W S W L IE A V Brickwall K Lane AR M58 E P Green N Virgin's LA Leatherbarrows Lane D Lane S R R Lane Y VE R A R E A W U E Q N Edge A L Lane K C Giddygate O R Lane NE Brewery LA R Lane TITHEBARN LANE Oaklands Crosby OO Melling Avenue M P R Chesterfield E LANE Waddicar S MOOR Road Lane C O T S L ISLINGTON S A 6 A P N 2 Y- E E B The Northern The Bootle Arms TH Road G L OV ER EN S D B B R Mill U T O Lane Liverpool T W L Road A N Great Crosby E 7 KIRKBY Brownmoor STATION Lane Kirkby Row E Liverpool IV Road D R Hall R D Lane D K KIRKBY CIVIC CENTRE RT L IR A E K U I B T F Y BUS STATION S -

1881 Census Index .For Lancashire for the Name

1881 CENSUS INDEX .FOR LANCASHIRE FOR THE NAME COMPILED BY THE INTERNATIONAL MOLYNEUX FAMILY ASSOCIATION COPYRIGHT: All rights reserved by the International Molyneux Family Association (IMFA). Permission is hereby granted to members to reproduce for genealogical libraries and societies as donations. Permission is also hereby granted to the Family History Library at 35 NW Temple Street, Salt Lake City, Utah to film this publication. No person or persons shall reproduce this publication for monetary gain. FAMILY REPRESENTATIVES: United Kingdom: IMFA Editor and President - Mrs. Betty Mx Brown 18 Sinclair Avenue, Prescot, Merseyside, L35 7LN Australia: Th1FA, Luke Molyneux, "Whitegates", Dooen RMB 4203, Horsham, Victoria 3401 Canada: IMFA, Marie Mullenneix Spearman, P.O. Box 10306, Bainbridge Island, WA 98110 New Zealand: IMFA, Miss Nulma Turner, 43B Rita Street, Mount Maunganui, 3002 South Africa: IMFA, Ms. Adrienne D. Molyneux, P.O. Box 1700, Pingowrie 2123, RSA United States: IMFA, Marie Mullenneix Spearman, P.O. Box 10306, Bainbridge Island, WA 98110 -i- PAGE INDEX FOR THE NAME MOLYNEUX AND ITS VARIOUS SPELLINGS COMPILED FROM 1881 CENSUS INDEX FOR LANCASHIRE This Index has been compiled as a directive to those researching the name MOLYNEUX and its derivations. The variety of spellings has been taken as recorded by the enumerators at the time of the census. Remember, the present day spelling of the name Molyneux which you may be researching may not necessarily match that which was recorded in 1881. No responsibility wiJI be taken for any errors or omi ssions in the compilation of this Index and it is to be used as a qui de only. -

Complete List of Roads in Sefton ROAD

Sefton MBC Department of Built Environment IPI Complete list of roads in Sefton ROAD ALDERDALE AVENUE AINSDALE DARESBURY AVENUE AINSDALE ARDEN CLOSE AINSDALE DELAMERE ROAD AINSDALE ARLINGTON CLOSE AINSDALE DORSET AVENUE AINSDALE BARFORD CLOSE AINSDALE DUNES CLOSE AINSDALE BARRINGTON DRIVE AINSDALE DUNLOP AVENUE AINSDALE BELVEDERE ROAD AINSDALE EASEDALE DRIVE AINSDALE BERWICK AVENUE AINSDALE ELDONS CROFT AINSDALE BLENHEIM ROAD AINSDALE ETTINGTON DRIVE AINSDALE BOSWORTH DRIVE AINSDALE FAIRFIELD ROAD AINSDALE BOWNESS AVENUE AINSDALE FAULKNER CLOSE AINSDALE BRADSHAWS LANE AINSDALE FRAILEY CLOSE AINSDALE BRIAR ROAD AINSDALE FURNESS CLOSE AINSDALE BRIDGEND DRIVE AINSDALE GLENEAGLES DRIVE AINSDALE BRINKLOW CLOSE AINSDALE GRAFTON DRIVE AINSDALE BROADWAY CLOSE AINSDALE GREEN WALK AINSDALE BROOKDALE AINSDALE GREENFORD ROAD AINSDALE BURNLEY AVENUE AINSDALE GREYFRIARS ROAD AINSDALE BURNLEY ROAD AINSDALE HALIFAX ROAD AINSDALE CANTLOW FOLD AINSDALE HARBURY AVENUE AINSDALE CARLTON ROAD AINSDALE HAREWOOD AVENUE AINSDALE CHANDLEY CLOSE AINSDALE HARVINGTON DRIVE AINSDALE CHARTWELL ROAD AINSDALE HATFIELD ROAD AINSDALE CHATSWORTH ROAD AINSDALE HEATHER CLOSE AINSDALE CHERRY ROAD AINSDALE HILLSVIEW ROAD AINSDALE CHESTERFIELD CLOSE AINSDALE KENDAL WAY AINSDALE CHESTERFIELD ROAD AINSDALE KENILWORTH ROAD AINSDALE CHILTERN ROAD AINSDALE KESWICK CLOSE AINSDALE CHIPPING AVENUE AINSDALE KETTERING ROAD AINSDALE COASTAL ROAD AINSDALE KINGS MEADOW AINSDALE CORNWALL WAY AINSDALE KINGSBURY CLOSE AINSDALE DANEWAY AINSDALE KNOWLE AVENUE AINSDALE 11 May 2015 Page 1 of 49 -

Crosby Hall and Little Crosby Conservation Area Advisory Leaflet

Metropolitan Borough of Sefton Advisory Leaflet Crosby Hall and Little Crosby Conservation Areas History Reformation they continued to hear mass secretly and The name Crosby has a Scandinavian ending –by, quietly in Crosby Hall or at one of the houses in the meaning a place or village, this indicates there has village, while facing heavy fines or even imprisonment if been a settlement here from before the time of the discovered. In 1611 William Blundell, the lord of the Domesday assessment in 1086. Crosby means “the manor, decided to give a portion of his estate to be place of the cross”. In general, until attempts were used as a Catholic burial ground after the burial of made in the 18th century to reduce the water table by Catholics was refused at Sefton Church, this site was drainage, the older settlements like Little Crosby were called the Harkirk which is an Old Norse word meaning sensibly related to outcrops of sandstone. These ‘grey church’ and it is believed that an ancient chapel outcrops also provided useful building materials for the had been established here by the early tenth century if local inhabitants. To improve the quality of agricultural not before. Many of the burials took place secretly at land, the use of marl (a limey clay) has been night and a hoard of silver Anglo-Saxon, Viking and widespread in Sefton since the medieval period, Continental coins was discovered on this site in 1611. evidence of marl pits can be found in the grounds of The hoard indicates “loot” which was of Scandinavian Crosby Hall. -

THE CHILD MARRIAGE of RICHARD, SECOND VISCOUNT MOLYNEUX, with SOME NOTICES of HIS LIFE, from CONTEMPORARY DOCUMENTS. by T. Alger

THE CHILD MARRIAGE OF RICHARD, SECOND VISCOUNT MOLYNEUX, WITH SOME NOTICES OF HIS LIFE, FROM CONTEMPORARY DOCUMENTS. By T. Algernon Earle, and R. D. Radcliffe, m.a., f.s.a. Read 5 th March, 1891. MONG the many interesting documents in A the muniment room at Croxteth, is a copy of a curious Case and Opinions, dated 12th July, 1648, relating to a contract of marriage, made when under age, by Richard, afterwards second Viscount Molyneux, and the Lady Henrietta Maria Stanley, daughter of the seventh Earl of Derby. Inasmuch as this gives an interesting statement of the law governing such contracts, and is a contemporary commentary on a custom, at the time it was written of frequent occurrence and long standing, it seems to be well worth recording at length. Of these " Child Marriages," Strype says in his Memorials (b. ii, p. 313), that " in the latter part of " the sixteenth century the nation became scan- " dalous for the frequency of divorces, especially " among the richer sort, one occasion being the " covetousness of the nobility and gentry, who " used often to marry their children when they " were young boys and girls, that they might join 246 Richard, second Viscount Molyneux. " land to land ; and, being grown up, they many " times disliked each other, and then separation "and divorce followed, to the breach of espousals " and the displeasure of God." Instances in our own two counties are numerous enough ; and, strange to say, the first Lord Moly- neux was in early life contracted in marriage to Fleetwood, daughter and heiress of Richard Barton, of Barton Row, co. -

Walking and Cycling Guide to Sefton’S Natural Coast

Walking and Cycling Guide to Sefton’s Natural Coast www.seftonsnaturalcoast.com Altcar Dunes introduction This FREE guide has been published to encourage you to get out and about in Southport and Sefton. It has been compiled to help you to discover Sefton’s fascinating history and wonderful flora and fauna. Walking or cycling through Sefton will also help to improve your health and fitness. With its wide range of accommodation to suit all budgets, Southport makes a very convenient base. So make the most of your visit; stay over one or two nights and take in some of the easy, family-friendly walks, detailed in this guide. Why not ‘warm-up’ by walking along Lord Street with its shops and cafés and then head for the promenade and gardens alongside the Marine Lake. Or take in the sea air with a stroll along the boardwalk of Southport Pier before walking along the sea wall of Marine Drive to the Queen’s Jubilee Nature Trail or the new Eco Centre nearby. All the trails and walks are clearly signposted and suitable for all ages and abilities. However, as with all outdoor activities, please take sensible precautions against our unpredictable weather and pack waterproof clothing and wear suitable shoes. Don’t forget your sun cream during the Summer months. If cycling, make sure that your bike is properly maintained and wear a protective helmet at all times. It's also a good idea to include some food and drink in a small day-pack, as although re-fuelling stops are suggested on the listed routes, there is no guarantee that they will be open when you need them. -

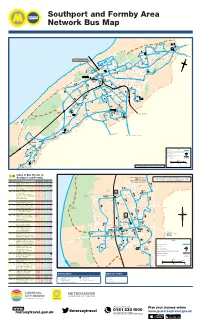

To Bus Routes in Southport and Formby

Southport and Formby Area Network Bus Map E M I V R A D R I N M E E A E N U I R N R E Harrogate Way A S V 40 M H A S Y O 40 A R D I W TRU S X2 to Preston D G R K H L I E I P E V A T M N R E O D 40 A R O C N 44 I R N L O O LSWI OAD O L A C R G K T Y E A V N A A E R . S D A E E RO ’ T K X2 G S N N R TA 40 E S 40 h RS t GA 44 A a W p O D B t A o P A R Fo I Y A 47.49 D V 40 l E ta C as 44 E Co n 44 fto 40 44 F Y L D E F e D S 15 40 R O A A I G R L Crossens W H E AT R O A D 40 A N ER V P X2 D M ROAD A D O THA E L NE H 15 Y R A O L N K A D E 347 W D O A S T R R 2 E ROA R O 347 K E D O . L A 47 E F Marshside R R D T LD 2 Y FIE 2 to Preston S H A ELL 49 A 15 SH o D D 347 to Chorley u W E N t V E I R 40 W R h R I N O M D A E p A L O o R F A r N F R t 15 R N E F N Golf O P I E S T O R A D X2 U A U H L ie 44 E N R M D N I F E R r Course E S LARK Golf V 347 T E D I C Southport Town Centre Marine D A E D N S H P U R A N E O E D A B Lake A Course I R R O A E 47 calls - N S V T R C 15.15 .40.44.46.46 .47.49.315(some)X2 R K V A E A E T N S HM E K R Ocean D I 2 E O M A L O O R A R L R R R IL O P Plaza P L H H B D A D O OO D E C AD A A R D 40 O A W 40 A S U 40 O N R T K 40 EE O 40 H R Y Y D L R E C LE F T L E S E E H U V W W L 15 O N I 49 KN Y R A R R G O D E R M O A L L S A R A A D M O E L M T E M I D B A Southport C R IDG E A E B Hesketh R S M I A N T C R S Hospital O E E E A Princes E 2 D E D R .1 P A A 5. -

Appendix a and B

APPENDIX A BIBLIOGRAPHY ILLUSTRATION SOURCES REFERENCES ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS BIBLIOGRAPHY BARRETT, Helena and PHILLIPS, John: Suburban Style – The British Home 1840 - 1960 [Pub: MacDonald & Co. Ltd. London 1987 (1988 Reprint)] Referenced in Sections: 5.0, 6.0 BOLGER, Paul The Dockers Umbrella - A History of Liverpool's Overhead Railway [Pub: Bluecoat Press Liverpool 1992 (1998 Reprint)] Referenced in Sections: 3.0 DIXON, Roger and MUTHESIUS, Stefan: Victorian Architecture [Pub: Thames & Hudson Ltd London 1978] Referenced in Sections: 6.0 HEATH, Tom : Images of England - Crosby, Seaforth and Waterloo [Pub: Tempus Publishing Ltd Stroud 2000] Referenced in Sections: 3.0 Photos: pp. 13 HEATH, Tom : Images of England - Crosby, Seaforth and Waterloo: The Second Selection [Pub: Tempus Publishing Ltd Stroud 2001] Referenced in Sections: 3.0 LEWIS, James R. : The Birth of Waterloo (3rd Edition – enlarged and revised by Andrew Farthing) [Pub: Sefton Council Leisure Services Southport 1996] Referenced in Sections: 3.0 Photos: pp 11 LONG, Helen : Victorian houses and their details – The role of publications in their building and decoration [Architectural Press Oxford 2002] Referenced in Sections: 7.0 MURRAY, Brenda : 200 years in Waterloo [printed by C S Digital Systems, Liverpool, 2015] PEVSNER, Nikolaus : Buildings of England – Lancashire Vol.1 The Industrial and Commercial South [Pub: Penguin Books Ltd London 1st published 1969 1993 Reprint] Referenced in Sections: 6.0 SMITH, Wilfred (Ed) : A Scientific Survey of Merseyside [Pub: University Press Liverpool 1953] Referenced in Sections: 2.0 STANISTREET, Jennifer & FARTHING, Andrew: Crosby in Camera - Early photographs of Great Crosby & Waterloo [Pub: Sefton Council Leisure Services Southport 1995] Referenced in Sections: 3.0, 5.0 Photos and illustrations: pp. -

Annual Report on Project Activity Year Two: Nov 2016 – Oct 2017

Red Squirrels United Annual report on project activity Year two: Nov 2016 – Oct 2017 LIFE14 NAT/UK/000467 Action C1 Urban IAS grey squirrel management in North Merseyside Executive Summary Activities under Action C1 have been underway throughout the North Merseyside and West Lancashire area, carried out by the Community Engagement Officer and Red Squirrel Ranger. Staffing issues have meant there has been a 2 month gap in the Ranger post and a new member of staff but the post is now stable and grey squirrel control throughout the designated areas continues. Grey squirrel control continues in the towns through the urban trap loan scheme. Participation in the trap loan scheme has increased in Crosby after a successful urban trap loan workshop but effort now needs to be focused in Southport and Maghull. The Community Engagement Officer has run 18 events and workshops throughout the project area in this time to increase community awareness regarding the impact of grey squirrels as a non-native invasive species, particularly on the red squirrel. There is real passion from the local community to see red squirrels in the Southport parks again and this drives support for grey squirrel control. Red and grey squirrel sightings continue to be received from members of the public and all sightings and grey squirrel control data are recorded in a format approved by Newcastle University for their data analysis. Introduction The North Merseyside and West Lancashire red squirrel population is the southernmost population in mainland England and has provided socio-economic benefits to the local economy through tourism, attracting approximately 300,000 visitors per year.