A:\Reappearing Masterpiece.Text.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art As a Site of Re-Orientation

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-1-2010 Exploring the Space of Resistance: Art as a Site of Re-Orientation Lauren Emily Stansbury Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Other Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Stansbury, Lauren Emily, "Exploring the Space of Resistance: Art as a Site of Re-Orientation" (2010). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 332. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/332 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Introduction I will begin by stating my interest lies in resistance. The beginnings of this project sprouted from an experience at the Hamburger Bahnhof museum of Berlin, in late fall of 2009. I visited the Hambuger to see a retrospective exhibition of the work of Joseph Beuys—an artist who I then only vaguely remembered from an obscure art history textbook, but an artist who has now become a brilliant North Star in my pantheon of cultural revolutionaries. The museum stands tall in white marble at the end of a long, gated courtyard. Once an open train station, the interior space is flooded with natural illumination. Tall ceilings expand the volume of the gallery; upon entering I felt dwarfed and cold. But despite the luxurious space, I was most intimidated by the obvious distaste the ticket attendant displayed for my clothing. -

For Immediate Release

For immediate release WARHOL: Monumental Series Make Premiere in Asia Yuz Museum Presents in Shanghai ANDY WARHOL, SHADOWS In collaboration with Dia Art Foundation, New York “I had seen Andy Warhol shows,but I was shocked when seeing more than a hundred of large paintings ! I felt so much respect for Warhol then and I was totally emotional in front of these Shadows: the first time shown as a complete piece as the original concept of Warhol. ” - Budi Tek, founder of Yuz Museum and Yuz Foundation -- -“a monument to impermanence” made by the “King of Pop”; - the most mysterious work of Warhol that offers profound and immersive experiences; - another ground-breaking one-piece work after the Rain Room at Yuz Museum; an important work from the collection of Dia Art Foundation; - Asian premiere after touring world’s top museums New York Dia: Beacon, Paris Museum of Modern Art and Bilbao Guggenheim; - a conversation between 1970s’Shadows and young artists of OVERPOP after 2010 -- Yuz Museum is proud to organize for the first time in Asia, the Chinese premiere of Shadows by Andy Warhol: “a monument to impermanence” (Holland Cotter, New-York Times). Shadows is valued as the most mysterious work by Andy Warhol, the most influential artist of the 20th century, “the King of Pop”, that shows the unknown side of the artist. The exhibition is presented in collaboration with the globally acclaimed Dia Art Foundation, New York. It opens at Yuz Museum, Shanghai on Saturday, 29th October, 2016. In 1978, at age 50, Andy Warhol embarked upon the production of a monumental body of work titled Shadows with the assistance of his entourage at the Factory. -

Cv-Ann-Reynolds-1.Pdf

ANN MORRIS REYNOLDS Department of Art and Art History University of Texas at Austin 2301 San Jacinto Blvd Stop D1300 Austin, TX 78712-1421 [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. THE GRADUATE SCHOOL AND UNIVERSITY CENTER OF THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK, NEW YORK, NY May 1993 20th century US and European art and architecture; critical theory; gender and sexuality Dissertation: “Robert Smithson: Learning from New Jersey and Elsewhere” with distinction WHITNEY INDEPENDENT STUDY PROGRAM 1979-1980 Curated Nineteenth Century Landscape Painting and the American Site. Whitney Museum of American Art Downtown Branch, 1980. B.A. SMITH COLLEGE, NORTHAMPTON, MA 1979 Art history major, studio minor; graduated cum laude PUBLICATIONS BOOKS In Our Time. Book-length project in progress. Robert Smithson. Du New Jersey au Yucatán, leçons d’ailleurs. Traduction: Anaël Lejeune et Olivier Mignon. Bruxelles: SIC Editions, 2014. Robert Smithson: Learning From New Jersey and Elsewhere. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003. EDITED Political Emotions. London: Routledge Press, 2010. Janet Staiger and ANTHOLOGIES Ann Cvetkovich, co-editors. ARTICLES “Distant et loin de tout,” Paris: Presses du Réel, forthcoming 2017, 145- 157. “How the Box Contains Us,” Joan Jonas: They Come to Us Without a Word. United Sates Pavilion, 56th International Art Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia. Edited by Jane Farver. Cambridge: MIT List Visual Arts Center, New York: Gregory R. Miller & Co. and Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2015, 18-27. “Operating in the Shadows: History’s Pilgrims,” Strange Pilgrims. Austin: Austin Contemporary and University of Texas Press, 2015, 35-40. “A History of Failure,” special issue on Jack Smith edited by Marc Siegel. -

Spiral Jetty, Geoaesthetics, and Art: Writing the Anthropocene Su Ballard University of Wollongong, [email protected]

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2019 Spiral Jetty, geoaesthetics, and art: Writing the Anthropocene Su Ballard University of Wollongong, [email protected] Elizabeth Linden University of Wollongong, [email protected] Publication Details Ballard, S. & Linden, E. "Spiral Jetty, geoaesthetics, and art: Writing the Anthropocene." The Anthropocene Review 6 .1-2 (2019): 142-161. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Spiral Jetty, geoaesthetics, and art: Writing the Anthropocene Abstract Despite the call for artists and writers to respond to the global situation of the Anthropocene, the 'people disciplines' have been little published and heard in the major journals of global environmental change. This essay approaches the Anthropocene from a new perspective: that of art. We take as our case study the work of American land artist Robert Smithson who, as a writer and sculptor, declared himself a 'geological agent' in 1972. We suggest that Smithson's land art sculpture Spiral Jetty could be the first marker of the Anthropocene in art, and that, in addition, his creative writing models narrative modes necessary for articulating human relationships with environmental transformation. Presented in the form of a braided essay that employs the critical devices of metaphor and geoaesthetics, we demonstrate how Spiral Jetty represents the Anthropocenic 'golden spike' for art history, and also explore the role of first-person narrative in writing about art. We suggest that art and its accompanying creative modes of writing should be taken seriously as major commentators, indicators, and active participants in the crafting of future understandings of the Anthropocene. -

Marian Goodman Gallery Robert Smithson

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY ROBERT SMITHSON Born: Passaic, New Jersey, 1938 Died: Amarillo, Texas, 1973 SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Robert Smithson: Time Crystals, University of Queensland, BrisBane; Monash University Art Museum, MelBourne 2015 Robert Smithson: Pop, James Cohan, New York, New York 2014 Robert Smithson: New Jersey Earthworks, Montclair Museum of Art, Montclair, New Jersey 2013 Robert Smithson in Texas, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas 2012 Robert Smithson: The Invention of Landscape, Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen, Unteres Schloss, Germany; Reykjavik Art Museum, Reykjavik, Iceland 2011 Robert Smithson in Emmen, Broken Circle/Spiral Hill Revisited, CBK Emmen (Center for Visual Arts), Emmen, the Netherlands 2010 IKONS, Religious Drawings and Sculptures from 1960, Art Basel 41, Basel, Switzerland 2008 Robert Smithson POP Works, 1961-1964, Art Kabinett, Art Basel Miami Beach, Miami, Florida 2004 Robert Smithson, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California; Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York 2003 Robert Smithson in Vancouver: A Fragment of a Greater Fragmentation, Vancouver Art Gallery, Canada Rundown, curated by Cornelia Lauf and Elyse Goldberg, American Academy in Rome, Italy 2001 Mapping Dislocations, James Cohan Gallery, New York 2000 Robert Smithson, curated by Eva Schmidt, Kai Voeckler, Sabine Folie, Kunsthalle Wein am Karlsplatz, Vienna, Austria new york paris london www.mariangoodman.com MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY Robert Smithson: The Spiral Jetty, organized -

Earthworks Ecosystems

Spiral Jetty Day for Science Teachers Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Educator Resources and Lesson Plans October 11, 2014 Spiral Jetty, Robert Smithson The monumental earthwork Spiral Jetty (1970) was created by artist Robert Smithson and is located off Rozel Point in the north arm of Great Salt Lake. Made of black basalt rocks and earth gathered from the site, Spiral Jetty is a 15-foot-wide coil that stretches more than 1,500 feet into the lake. Un- doubtedly the most famous large-scale earthwork of the period, it has come to epitomize Land art. Its exception- al art historical importance and its unique beauty have drawn visitors and media attention from throughout Utah and around the world. Rozel Point attracted Smithson for a number of reasons, including its remote location and the reddish quality of the water in that section of the lake (an effect of bacteria in the water). Using natural materials from the site, Smithson designed Spiral Jetty to extend into the lake several inches above the waterline. However, the earthwork is affected by seasonal fluctuations in the lake level, which can alternately submerge the Jetty or leave it completely exposed and covered in salt crystals. The close communion between Spiral Jetty and the super-saline Great Salt Lake emphasizes the entropic processes of erosion and physical disorder with which Smithson was continually fascinated. The Utah Museum of Fine Arts works in collaboration with the Dia Art Foundation and the Great Salt Lake Institute at Westminster College to preserve, maintain, and advocate for this masterpiece of late twentieth-century art and acclaimed Utah landmark. -

Chapter 13: Sculpture

Chapter 13: Sculpture One of the oldest and most enduring of all the arts. Sculptures uses the visual elements of actual space and actual texture. There are three forms of sculptural space: • relief • in the round Elements, • as an environment Each type of sculpture employs two basic processes: either an additive Forms, and process or a subtractive process. • Subtractive Process: begins with a mass of material larger than the Types finished work, and removes material, or subtracts from that mass until the work achieves its finished form. • Additive Process: the sculptor builds the work, adding material as the work proceeds. Types of Sculpture Additive • Modeling • Assemblage (construction) • Earthworks Subtractive • Carving • Earthworks Sarah Sze, Triple Point Pendulum, 2013 This is an example of an additive work. Sze is known for densely arranged groupings of objects. She says “Improvisation is crucial. I want the work to be sort of an experience of something alive- to have this feeling that it was improvised, that way you can see decisions happening on site, the way you see a live sports event, the way you hear jazz.” A relief is a sculpture that has three dimensional depth but is meant to be seen from only one side. It is frontal- meant to be viewed from the front. It’s often used to decorate architecture. Relief There are two categories of relief: Low Relief: the depth is very shallow (extends less than 180 degrees from the base) High Relief: project forward from their base by at least half their depth LOW RELIEF SCULPTURE Title: Senwosret I led by Atum to Amun-Re Artist: n/a Date: c. -

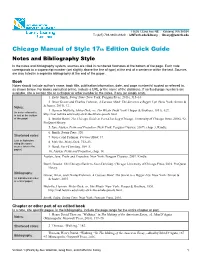

Lwtech Chicago Manual of Style 17Th Edition Quick Guide

11605 132nd Ave NE | Kirkland, WA 98034 T: (425) 739-8100 x8320 | LWTech.edu/Library | [email protected] Chicago Manual of Style 17th Edition Quick Guide Notes and Bibliography Style In the notes and bibliography system, sources are cited in numbered footnotes at the bottom of the page. Each note corresponds to a superscript number (set slightly above the line of type) at the end of a sentence within the text. Sources are also listed in a separate bibliography at the end of the paper. Book Notes should include author’s name, book title, publication information, date, and page number(s) quoted or referred to, as shown below. For books consulted online, include a URL or the name of the database. If no fixed page numbers are available, cite a section title or a chapter or other number in the notes, if any (or simply omit). 1. Zadie Smith, Swing Time (New York: Penguin Press, 2016), 315–16. 2. Brian Grazer and Charles Fishman, A Curious Mind: The Secret to a Bigger Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015), 12. Notes: 3. Herman Melville, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1851), 627, (in order referred to in text at the bottom http://mel.hofstra.edu/moby-dick-the-whale-proofs.html. of the page) 4. Brooke Borel, The Chicago Guide to Fact-Checking (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 92, ProQuest Ebrary. 5. Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice (New York: Penguin Classics, 2007), chap. 3, Kindle. 6. Smith, Swing Time, 320. Shortened notes: 7. Grazer and Fishman, Curious Mind, 37. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 29, 2016 Dia Art Foundation to Open Two New Installations at Dia:Chelsea on November 5, 2016 Collecti

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 29, 2016 Dia Art Foundation to Open Two New Installations at Dia:Chelsea on November 5, 2016 Collection reinstallation of Hanne Darboven’s Kulturgeschichte 1880–1983 (Cultural History 1880– 1983, 1980–83) First solo museum exhibition in the United States by Kishio Suga featuring a new commission New York, NY – This fall Dia Art Foundation will present two new installations at Dia:Chelsea. Kishio Suga and Hanne Darboven’s Kulturgeschichte 1880–1983 (Cultural History 1880–1983, 1980–83) will be on view from November 5, 2016, to July 30, 2017. These new programs continue to demonstrate Dia’s commitment to presenting artworks that invite sustained interest and contemplation from visitors, scholars, and artists alike. Additionally, they trace relationships, formal dialogues, and conceptual parallels among international artistic practices that are historically and intellectually linked to Dia’s focused collection of art from the 1960s and 1970s. Kishio Suga November 5, 2016– July 30, 2017 Beginning November 5, 2016, Dia will present an exhibition of Kisho Suga’s work at Dia:Chelsea at 541 West 22nd Street in New York City. Suga is a founding members of Mono-ha (School of Things), which emerged in Japan in the 1960s and 1970s and developed in parallel with Postminimal and Land art in the United States and Arte Povera in Europe—movements at the core of Dia’s permanent collection. This will be Suga’s first solo museum show in the United States. In this exhibition, Suga will respond to the building’s unique history as a marble-cutting facility by recreating his Placement of Condition (1973), a signature installation of cut stones that lean precariously away from each other, but are bound together with wire into a mutually dependent and stable network. -

Dia Chelsea, Reimagined, Reopens to the Public This Week After Renovation by Architecture Research Office

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 14, 2021 DIA CHELSEA, REIMAGINED, REOPENS TO THE PUBLIC THIS WEEK AFTER RENOVATION BY ARCHITECTURE RESEARCH OFFICE Part of a comprehensive, multi-year plan to strengthen and revitalize Dia’s constellation of sites in Chelsea, Beacon, and SoHo, as well as renovation of two landmark artist installations New York, NY – Dia Art Foundation and Architecture Research Office (ARO) are celebrating the completion and the public reopening of Dia Chelsea. Established in 1974, Dia Art Foundation supports the vision of artists through organizing and commissioning permanent and long-term exhibitions and installations at its constellation of sites in the United States and Germany. Dia’s collection spotlights in particular the work of artists from 1960s and 1970s, ranging from site-specific Land art such as Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels and Walter de Maria’s The Lightning Field, to significant works by Sam Gilliam, Richard Serra, Donald Judd, Agnes Martin, Andy Warhol and many other acclaimed artists of the past half-century. Dia originated the concept of repurposing old factories and warehouses to create generous daylit spaces for art outside the context of the ‘white cube’ museum or gallery. In the 1980’s, Dia relocated its offices and exhibition space to the west Chelsea area of New York City, a formerly industrial neighborhood that is now home to more than 200 galleries. In 2003, Dia opened Dia Beacon in upstate New York, in a nearly 300,000 square foot former Nabisco box printing factory boasting more than 34,000-square-feet of skylights. The renovation and expansion of Dia Art Foundation’s three adjacent buildings in Chelsea establishes a greater street-level public presence for Dia. -

Art and Architecture: a Place Between Jane Rendell

Art and Architecture: A Place Between Jane Rendell 1 For Beth and Alan 2 Contents List of Figures Preface Acknowledgements Introduction: A Place Between A Place Between Art and Architecture: Public Art A Place Between Theory and Practice: Critical Spatial Practice Section 1: Between Here and There Introduction: Space, Place and Site Chapter 1: Site, Non-Site, Off-Site Chapter 2: The Expanded Field Chapter 3: Space as Practised Place Section 2: Between Now and Then Introduction: Allegory, Montage and Dialectical Image Chapter 1: Ruin as Allegory Chapter 2: Insertion as Montage Chapter 3: The ‘What-has-been’ and the Now. Section 3: Between One and Another Introduction: Listening, Prepositions and Nomadism Chapter 1: Collaboration Chapter 2: Social Sculpture Chapter 3: Walking Conclusion: Criticism as Critical Spatial Practice Bibliography 3 List of Illustrations Cover 1 ‘1 ‘A Place Between’, Maguire Gardens, Los Angeles Public Library reflected in the pool of Jud Fine’s art work ‘Spine’ (1993). Photograph: Jane Rendell, (1999). Section 1 Chapter 1 2 Robert Smithson, ‘Spiral Jetty’ (1970), Salt Lake, Utah. Photograph: Cornford & Cross (2002). 3 Walter de Maria, ‘The New York Earth Room’, (1977). Long-term installation at Dia Center for the Arts, 141 Wooster Street, New York City. Photograph: John Cliett © Dia Art Foundation. 4 Joseph Beuys, ‘7000 Oaks’ (1982–), New York. Photo: Cornford & Cross (2000). 5 Dan Graham, ‘Two-Way Mirror Cylinder Inside Cube’ (1981/1991), Part of the Rooftop Urban Park Project. Long-term installation at Dia Center for the Arts, 548 West 22nd Street, New York City. Photo: Bill Jacobson. Courtesy Dia Center for the Arts. -

Science Fictional Transcendentalism in the Work of Robert Smithson

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design Art, Art History and Design, School of 8-2013 Science Fictional Transcendentalism in the Work of Robert Smithson Eric Saxon University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Saxon, Eric, "Science Fictional Transcendentalism in the Work of Robert Smithson" (2013). Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design. 43. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents/43 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art, Art History and Design, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SCIENCE FICTIONAL TRANSCENDENTALISM IN THE WORK OF ROBERT SMITHSON by Eric Saxon A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Art History Under the Supervision of Professor Marissa Vigneault Lincoln, Nebraska August 2013 ii SCIENCE FICTIONAL TRANSCENDENTALISM IN THE WORK OF ROBERT SMITHSON Eric James Saxon, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2013 Advisor: Marissa Vigneault In studies of American artist Robert Smithson (1938-1973), scholars often set the artist’s early abstract expressionist and Christian iconographical paintings apart from the rest of his body of work, characterizing this early phase as a youthful encounter with the enduring legacy of abstract expressionism in the late 1950s to early 1960s as well as a temporary preoccupation with ritualized Catholic imagery.