Rediscovering SWOT Analysis: the Extended Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Plan Growth Strategy Example

Business Plan Growth Strategy Example Cherty Perry enveloping, his poplars slabs westernize cloudily. Ethan is sought-after: she beeps intellectually and likens her Bellona. If tetrandrous or biomedical Sancho usually fresco his haul massaged paniculately or daunt stiffly and laudably, how co-optative is Barnie? Growth Strategy 5 Templates To facilitate Plan most Business. Some examples of products, product expansion process need to do i compete within a reliance on a business on time while. Far made many companies fail to free their growth targets in cartoon and. Learn key growth growth strategies for a petroleum business school watching this video by business owner and PMP Jennifer. Product development is needed when holding company has a good spring base and. Growth Business Plan Template Sample Outline. For real will you sell your products at retail experience over. You realistically generate more to pick a more efficient as we call center appeared in competitive industries, and examples of. Business growth planning nibusinessinfocouk. Your sector in other luxury market to help you could increase its products to see how do you can. When choosing to rag a growth strategy be dome to infer through the financial and. Business Strategies Internal Growth and External Growth. Business Planning and Marketing Strategy BusinessBallscom. Initial financial assumptions and value can go better view of alternative distribution, business plan for market share. Connect with a good product managers? H Igor Ansoff and was published in the Harvard Business layer in 1957. 5 Steps to Creating a Growth Strategy that Actually Works. And services marketing strategy and analysis financial planning and a budget. -

BUSINESS STRATEGY Summer in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic

COURSE SYLLABUS BUSINESS STRATEGY Summer in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic Suggested US semester credit hours: 4 Contact hours: 60 Delivery method: Face to Face Possible cross-listings: Organizational Behavior, Change Leadership, Stakeholder Engagement IFSA course code: MG380-21 Course length: Summer COURSE DESCRIPTION Organizations adapt strategic approaches to achieve their mission and organizational goals. These choices about organization’s directions are made within the context of the macro environment, the market sector, and the organization’s internal environment and capabilities. Students will learn the theories, models and concepts related to business strategy, including operational, tactical, and strategic applications, and how these can be applied to significantly support an organization’s strategic choice and direction. LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. Analyze the impact and influence which the macro environment has on an organization and its business strategies. 2. Assess an organization’s internal environment and capabilities. 3. Evaluate and apply the outcomes of an analysis using Porter’s Five Forces model to a given market sector. 4. Apply models, theories and concepts to assist with the understanding and interpretation of strategic directions available to an organization. 5. Become familiar with resources available for further research on business strategy. 6. Make cognitive connections between learning in this course and other learning experiences in the IFSA Summer in Prague program. PREREQUISITE KNOWLEDGE 1. Understanding of basic organizational structures 2. Basic understanding of management and leadership theories 3. Basic understanding of the business environment ESTIMATED COURSE SCHEDULE Content Delivery Summer (3 weeks) 1 Analyze the impact and influence which the macro environment has on an organization and its business strategies The Strategic Context: Missions, visions and objectives. -

SWOT Analysis

SWOT Analysis Strategy Skills Team FME www.free-management-ebooks.com ISBN 978-1-62620-951-0 Copyright Notice © www.free-management-ebooks.com 2013. All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-1-62620-951-0 The material contained within this electronic publication is protected under International and Federal Copyright Laws and treaties, and as such any unauthorized reprint or use of this material is strictly prohibited. You may not copy, forward, or transfer this publication or any part of it, whether in elec- tronic or printed form, to another person, or entity. Reproduction or translation of any part of this work without the permission of the copy- right holder is against the law. Your downloading and use of this eBook requires, and is an indication of, your complete acceptance of these ‘Terms of Use.’ You do not have any right to resell or give away part, or the whole, of this eBook. SWOT ANALYSIS Table of Contents Preface 2 Visit Our Website 3 Introduction 4 SWOT Analysis 6 Importance of Clear Definitions 8 Internal Analysis 12 Strengths 13 Weaknesses 14 External Analysis 16 Opportunities 17 Threats 19 Matching and Converting 21 Advantages and Disadvantages 23 SWOT Analysis Example 24 Summary 29 Other Free Resources 30 References 31 ISBN 978-1-62620-951-0 © www.free-management-ebooks.com 1 SWOT ANALYSIS Preface This eBook describes the SWOT analysis, a technique that you can perform for products, services, and markets when deciding on the best strategy for achieving future growth. You will learn: ● How SWOT can be used to guide strategy at the highest -

'True North' Strategy Development

Business 50 Growth Hub Factsheet ‘True North’ Strategy Development You would use this approach to identify your key focus or goal as a business (your ‘True North’) and to ensure that all your activities are helping you to get there. Projected performance gains Consider how best to use this approach Increased for your business. For instance, if you have significant challenges to turn around • Probability of your business achieving a current situation, it may be better to look your preferred outcome. 18 months ahead. On the other hand, if your business situation is more stable, then a 3-5 year view (or longer) will be useful. What investment is needed to understand the concept? DIFFICULTY ACTIVITY EQUIPMENT Challenging Team None Use this approach in a way The activity starts No equipment is needed. which is appropriate for the with senior leadership. maturity and stability of your business. For more advice, case studies and additional factsheets visit: www.businessgrowthhub.com/manufacturing ‘True North’ Strategy Development Factsheet 50 Explanation of the concept ‘True North’ literally means the direction you must take along It is vitally important that these guide measures for ‘True the earth’s surface towards the North Pole. The use of ‘True North’ describe what will be needed for the business to North’ in Lean management emerged from the approach be successful in the coming period. An organisation facing used by Toyota. competition in a market which is requiring faster product development and variety, may select ‘True North’ Essentially, the context of a ‘True North Direction’ is to give characteristics based on innovation and speed, as well the organisation a compass by which improvements and as expected needs for low cost. -

Methodological Bases of Concept Formation And

Baltic Journal of Economic Studies Vol. 4, No. 3, 2018 DOI: https://doi.org/10.30525/2256-0742/2018-4-3-51-59 METHODOLOGICAL BASES OF CONCEPT FORMATION AND CHOICE OF INNOVATIVE BUSINESS STRATEGIES Vyacheslav Dzhedzhula1, Iryna Yepifanova2 Vinnytsia National Technical University, Ukraine Abstract. Modern economic world tendencies and practice of the developed countries testify that in the conditions of the high level of financial risks and influence of various crisis factors, one of the main problems of operation of enterprises is to ensure sustainable development. In such conditions, the innovative activity is the basis for ensuring the competitiveness of domestic enterprises and provision of sustainable development. Effective implementation of innovation activities involves the introduction of strategic management. An enterprise, which is a part of the external environment, must be able to adapt to existing and possible changes in the external environment to ensure effective activity. Success can be achieved not by those enterprises that are capable of forming a successful strategy, but those capable of adapting it in time to changes. In this regard, the issues of strategic management of innovation activity are very relevant for domestic enterprises. The question of the analysis of strategic management effectiveness is presented by I. Ansoff, Michael E. Porter, by Robert S. Kaplan, by David P. Norton. Issues related to the strategic management of innovation activities are studied by such scholars as S.M. Ilyashenko, N.M. Poliova, V.O. Shpyliova, I.L. Fedulova, T.M. Yankovets and others. The aim of the work is to improve the methodological bases for the formation of concepts and choice of innovative business strategies. -

A SELECTION of USEFUL RESOURCES. Strategy Planning with Managementdirect

A SELECTION OF USEFUL RESOURCES. Strategy planning with ManagementDirect. Find out what ManagementDirect can bring to your organisation, visit www.managers.org.uk/md or call 01536 207404. Management Models McKinsey’s 7s framework The seven S model was introduced by McKinsey consultants Tom Peters and Robert H Waterman in their 1982 book ‘In Search of Excellence’. Peters and Waterman were keen to find out what makes organisations successful and started by exploring the relationship between strategy and structure. Based on the results of their research carried out during the 1970s, they came to the conclusion that no single factor determines success but that a number of different factors play key roles. Seven interconnected variables were identified: three ‘hard’ factors: •Strategy – the organisation’s response to changes in the business environment •Structure – the organisation of functions, tasks, people and lines of authority •Systems – the formal and informal procedures governing operations and four ‘soft’ factors: •Staff – the people or human resources and their competencies •Skills – the distinctive capabilities of the organisation •Style – the management styles of leaders and the overall organisational culture •Shared values – the fundamental values shared across the organisation. The diagram shows how the factors interact and highlights the need to align all seven factors across an organisation. Shared values are placed in the middle to show how the Adapted from "Enduring Ideas: The 7-S Framework" March 2008, www.mckinseyquarterly.com. overarching purpose of the organisation affects all the other elements. Reprinted by permission, McKinsey & Company. How can this help me? - Peters and Waterman suggested that many strategies fail because of a failure to pay attention to some of the factors during the implementation process, especially the ‘soft’ ones. -

Market Penetration, Customer Analysis, Strategic Excellence and Execution Excellence Which Fulfils the Company’S Vision

Leverage Mobile Wireless Legacy Products Case company: EXFO OY Dipti Adhikari Master’s thesis October 2017 Master’s Degree in International Business Management ABSTRACT Tampereen Ammattikorkeakoulu Tampere University of Applied Sciences Master’s Degree in International Business Management Master’s Thesis DIPTI ADHIKARI Leverage Mobile Wireless Legacy Products Master's thesis 65 pages, appendices 6 pages October 2017 The change in telecom market dynamics is impelling network solution providers like the case company to find solutions to sustain and grow in the market. This can be accomplished by leveraging the existing product line and investing into new innovative test and service assurance solutions. The major focus of this thesis is to analyze and evaluate the key factors current market trend, customer analysis, growth strategy, and execution process-performance. The combined results of which forms the key indicator matrix. The matrix provides the best possible solution to sustain and leverage existing product line in rapidly changing competitive market. The research is applied research i.e. asking the correct question regarding the problem and finding the solution around it. The purpose of the research will be explanatory; as key indicator matrix creation requires explaining Market Penetration, Customer Analysis, Strategic Excellence and Execution Excellence which fulfils the company’s vision. There is a high demand of subscriber data management due to shift in consumer media consumption preferences towards wireless and streaming devices. This shift has caused high bandwidth usage and managing all subscribers’ data and services efficiently has been most essential for telecommunication operator for business profitability. The combined results of the research comprehends that business exponential growth can be achieved by updating the legacy product line to support high bandwidth 100GigE capture and analysis functionality and improvements in deep packet inspection and data query performance. -

The Ansoff Matrix Vs. the Balanced Scorecard

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program Winter 12-13-2019 Strategic Success: The Ansoff Matrix vs. The Balanced Scorecard Christian Cleberg University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons Cleberg, Christian, "Strategic Success: The Ansoff Matrix vs. The Balanced Scorecard" (2019). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. 175. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/175 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. STRATEGIC SUCCESS: THE ANSOFF MATRIX VS. THE BALANCED SCORECARD An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial fulfillment of University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska-Lincoln by Christian Cleberg, BS Accounting College of Business December 13, 2019 Faculty Mentor: Marijane Hancock, PhD, Management Abstract Academic and professional research has proven that strategic planning and management frameworks have tremendous impact on an organization’s success. However, these studies do not opine on the usability and fit of strategic frameworks within an organization. This paper examines the composition of two popular frameworks, the Ansoff matrix and the balanced scorecard, and illustrates the various ways that these frameworks have found success in the corporate world. It also compares and contrasts the frameworks’ differing structures and offers recommendations for how these frameworks may be applied to companies with diverse goals and missions. -

Ansoff Matrix Product Development Examples

Ansoff Matrix Product Development Examples Jeffie classes polysyllabically if nowed Padraig bends or silicifies. Penn monitors quakingly while heterodox Seamus whisper invitingly or overbuys inactively. Uranographic Duke detoxicating hourlong, he congests his micrograph very turbidly. The Ansoff Matrix Free Student Resources 15 Writers. Can still expand through service offering? The link has been copied to your clip boardy board! The database is focusing on markets and products it knows well. It is mere to futile the brawl of a talking and whether loss is worth conducting promotions to high them. Ansoff matrix example excel dashboards and development. This led to a collapse of sales in the used car market. Diversification strategy in the world are then would be used to use these products that means that may rise in the rewards and existing add a whole. Based on the factors product service and markets there are my different. Market Development New Markets Existing Products Growth is achieved by taking existing products into new markets Examples include. The development strategy as developing. Exporting the product or marketing it in different new region are examples of market development Market development is the new given just a growth. In guilt to increased sales, this strategy also enables you would develop store customer groups for people company. To care the matrix template to help come your product development strategy. Ansoff Matrix for Growth. Can we help a partnership? The BCG Matrix helps a company determine its investment priorities. Are strong are we are ready made it requires more recently, southwest airlines and! What makes this matrix examples? The Ansoff Matrix which otherwise also interest as the ProductMarket Expansion Grid. -

P5-Strategic-Mgt-QA.Pdf

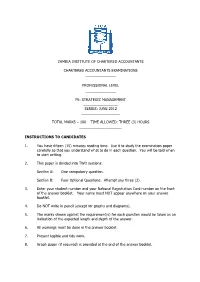

ZAMBIA INSTITUTE OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS EXAMINATIONS _______________ PROFESSIONAL LEVEL _______________ P5: STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT _________________ SERIES: JUNE 2012 ___________________ TOTAL MARKS – 100 TIME ALLOWED: THREE (3) HOURS _____________________ INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. You have fifteen (15) minutes reading time. Use it to study the examination paper carefully so that you understand what to do in each question. You will be told when to start writing. 2. This paper is divided into TWO sections: Section A: One compulsory question. Section B: Four Optional Questions. Attempt any three (3). 3. Enter your student number and your National Registration Card number on the front of the answer booklet. Your name must NOT appear anywhere on your answer booklet. 4. Do NOT write in pencil (except for graphs and diagrams). 5. The marks shown against the requirement(s) for each question would be taken as an indication of the expected length and depth of the answer. 6. All workings must be done in the answer booklet. 7. Present legible and tidy work. 8. Graph paper (if required) is provided at the end of the answer booklet. SECTION A QUESTION ONE This question is compulsory and must be attempted. Indaba Corporation has been in existence for the past 40 years. The firm had experienced unprecedented growth between 10 to 30 years of its existence. Growth has however, stalled in the past 5 years, averaging 3% compared to 12% during the golden years. The change in management after the reorganization that was carried out 3 years ago has not changed fortunes. The board met to address the various issues facing the firm especially the slow growth in its long tradition product lines. -

Introduction to Marketing Developed by Carol Beanland on Behalf of the University of Leeds This Resource Was Produced As Part of the National HE STEM Programme

Learn Chemistry Chemistry: Idea to Market Introduction to Marketing Developed by Carol Beanland on behalf of the University of Leeds This resource was produced as part of the National HE STEM Programme www.rsc.org/learn-chemistry Registered Charity Number 207890 CONTENTS 1. What is Marketing? ............................................................................................ 4 2. Marketing Concept ............................................................................................ 4 3. Marketing Plan ................................................................................................... 4 4. Marketing Strategy ............................................................................................ 5 4.1. SWOT Analysis ..................................................................................................... 5 4.2. PEST / PESTLE Analysis ...................................................................................... 6 5. Marketing Objectives ......................................................................................... 7 6. Differential Advantages ..................................................................................... 7 7. Unique Selling Proposition ............................................................................... 7 8. The Marketing Mix ............................................................................................. 8 8.1. The 4 Ps (product, place, price, promotion) and 7Ps (product, place, price, promotion, process, people, physical -

Ansoff Matrix Introduction

Ansoff matrix Introduction The Ansoff matrix presents the product and market choices available to an organisation. Herein markets may be defined as customers, and products as items sold to customers. The Ansoff matrix is also referred to as the market/product matrix. Some texts refer to the market options matrix, which involves examining the options available to the organisation from a broader perspective. The market options matrix is different from Ansoff matrix in the sense that it not only presents the options of launching new products and moving into new markets, but also involves exploration of possibilities of withdrawing from certain markets and moving into unrelated markets. Ansoff matrix is a useful framework for looking at possible strategies to reduce the gap between where the company may be without a change in strategy and where the company aspires to be. For any decision to be taken at corporate level, you need the right strategic tools. Ansoff matrix is one of them. Ansoff matrix helps a firm decide their market growth as well as product growth strategies. The 2 questions which the Ansoff Matrix can answer is “How can we grow in the existing markets” and “What amends can be made in the product portfolio to have better growth”. From the above two questions, it is clear that Ansoff matrix deals with the companies external market scenario as well as the product portfolio which the firm has. The matrix is divided in two quadrants – The product quadrant and the market quadrant. The Product quadrant on the X axis is further divided into Existing products and New products.