Cretaceous Bird with Dinosaur Skull Sheds Light on Avian Cranial Evolution ✉ Min Wang 1,2 , Thomas A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tiny Fossil Sheds Light on Miniaturization of Birds

Retraction Tiny fossil sheds light on miniaturization of birds Roger B. J. Benson Nature 579, 199–200 (2020) In view of the fact that the authors of ‘Hummingbird-sized dinosaur from the Cretaceous period of Myanmar‘ (L. Xing et al. Nature 579, 245–249; 2020) are retracting their report, I wish to retract this News & Views article, which dealt with this study and was based on the accuracy and reproducibility of their data. Nature | 22 July 2020 ©2020 Spri nger Nature Li mited. All rights reserved. drives the assembly of DNA-PK and stimulates regulation of protein synthesis. And, although 3. Dragon, F. et al. Nature 417, 967–970 (2002). its catalytic activity in vitro, although does so further studies are required, we might have 4. Adelmant, G. et al. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 11, 411–421 (2012). much less efficiently than can DNA. taken a step closer to deciphering the 5. Britton, S., Coates, J. & Jackson, S. P. J. Cell Biol. 202, Taken together, these observations suggest mysterious ribosomopathies. 579–595 (2013). a model in which KU recruits DNA-PKcs to the 6. Barandun, J. et al. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 24, 944–953 (2017). small-subunit processome. In the case of Alan J. Warren is at the Cambridge Institute 7. Ma, Y. et al. Cell 108, 781–794 (2002). kinase-defective DNA-PK, the mutant enzyme’s for Medical Research, Hills Road, Cambridge 8. Yin, X. et al. Cell Res. 27, 1341–1350 (2017). inability to regulate its own activity gives the CB2 OXY, UK. 9. Sharif, H. et al. -

(Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Wulansuhai Formation of Inner Mongolia, China

Zootaxa 2403: 1–9 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new dromaeosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Wulansuhai Formation of Inner Mongolia, China XING XU1, JONAH N. CHOINIERE2, MICHAEL PITTMAN3, QINGWEI TAN4, DONG XIAO5, ZHIQUAN LI5, LIN TAN4, JAMES M. CLARK2, MARK A. NORELL6, DAVID W. E. HONE1 & CORWIN SULLIVAN1 1Key Laboratory of Evolutionary Systematics of Vertebrates, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology & Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 142 Xiwai Street, Beijing 100044. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Biological Sciences, George Washington University, 2023 G Street NW, Washington, DC 20052, USA 3Department of Earth Sciences, University College London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, UK 4Long Hao Institute of Geology and Paleontology, Hohhot, Nei Mongol 010010, China 5Department of Land and Resources, Linhe, Nei Mongol 015000, China 6Division of Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th St., New York, 10024, USA Abstract We describe a new dromaeosaurid theropod from the Upper Cretaceous Wulansuhai Formation of Bayan Mandahu, Inner Mongolia. The new taxon, Linheraptor exquisitus gen. et sp. nov., is based on an exceptionally well-preserved, nearly complete skeleton. This specimen represents the fifth dromaeosaurid taxon recovered from the Upper Cretaceous Djadokhta Formation and its laterally equivalent strata, which include the Wulansuhai Formation, and adds to the known diversity of Late Cretaceous dromaeosaurids. Linheraptor exquisitus closely resembles the recently reported Tsaagan mangas. Uniquely among dromaeosaurids, the two taxa share a large, anteriorly located maxillary fenestra and a contact between the jugal and the squamosal that excludes the postorbital from the infratemporal fenestra. -

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber's Advocacy for Gender

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber’s Advocacy for Gender Equality in Ornithology TANJA HAMMEL Department of History, University of Basel This article explores parts of the first South African woman ornithologist’s life and work. It concerns itself with the micro-politics of Mary Elizabeth Barber’s knowledge of birds from the 1860s to the mid-1880s. Her work provides insight into contemporary scientific practices, particularly the importance of cross-cultural collaboration. I foreground how she cultivated a feminist Darwinism in which birds served as corroborative evidence for female selection and how she negotiated gender equality in her ornithological work. She did so by constructing local birdlife as a space of gender equality. While male ornithologists naturalised and reinvigorated Victorian gender roles in their descriptions and depictions of birds, she debunked them and stressed the absence of gendered spheres in bird life. She emphasised the female and male birds’ collaboration and gender equality that she missed in Victorian matrimony, an institution she harshly criticised. Reading her work against the background of her life story shows how her personal experiences as wife and mother as well as her observation of settler society informed her view on birds, and vice versa. Through birds she presented alternative relationships to matrimony. Her protection of insectivorous birds was at the same time an attempt to stress the need for a New Woman, an aspect that has hitherto been overlooked in studies of the transnational anti-plumage -

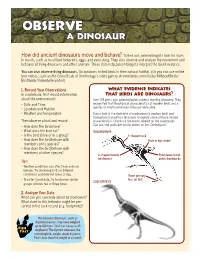

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

A New Raptorial Dinosaur with Exceptionally Long Feathering Provides Insights Into Dromaeosaurid flight Performance

ARTICLE Received 11 Apr 2014 | Accepted 11 Jun 2014 | Published 15 Jul 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5382 A new raptorial dinosaur with exceptionally long feathering provides insights into dromaeosaurid flight performance Gang Han1, Luis M. Chiappe2, Shu-An Ji1,3, Michael Habib4, Alan H. Turner5, Anusuya Chinsamy6, Xueling Liu1 & Lizhuo Han1 Microraptorines are a group of predatory dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaurs with aero- dynamic capacity. These close relatives of birds are essential for testing hypotheses explaining the origin and early evolution of avian flight. Here we describe a new ‘four-winged’ microraptorine, Changyuraptor yangi, from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota of China. With tail feathers that are nearly 30 cm long, roughly 30% the length of the skeleton, the new fossil possesses the longest known feathers for any non-avian dinosaur. Furthermore, it is the largest theropod with long, pennaceous feathers attached to the lower hind limbs (that is, ‘hindwings’). The lengthy feathered tail of the new fossil provides insight into the flight performance of microraptorines and how they may have maintained aerial competency at larger body sizes. We demonstrate how the low-aspect-ratio tail of the new fossil would have acted as a pitch control structure reducing descent speed and thus playing a key role in landing. 1 Paleontological Center, Bohai University, 19 Keji Road, New Shongshan District, Jinzhou, Liaoning Province 121013, China. 2 Dinosaur Institute, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90007, USA. 3 Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, 26 Baiwanzhuang Road, Beijing 100037, China. 4 University of Southern California, Health Sciences Campus, BMT 403, Mail Code 9112, Los Angeles, California 90089, USA. -

Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor How They Arise, Modify and Vanish

Fascinating Life Sciences Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor Bird Species How They Arise, Modify and Vanish Fascinating Life Sciences This interdisciplinary series brings together the most essential and captivating topics in the life sciences. They range from the plant sciences to zoology, from the microbiome to macrobiome, and from basic biology to biotechnology. The series not only highlights fascinating research; it also discusses major challenges associated with the life sciences and related disciplines and outlines future research directions. Individual volumes provide in-depth information, are richly illustrated with photographs, illustrations, and maps, and feature suggestions for further reading or glossaries where appropriate. Interested researchers in all areas of the life sciences, as well as biology enthusiasts, will find the series’ interdisciplinary focus and highly readable volumes especially appealing. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15408 Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor Bird Species How They Arise, Modify and Vanish Editor Dieter Thomas Tietze Natural History Museum Basel Basel, Switzerland ISSN 2509-6745 ISSN 2509-6753 (electronic) Fascinating Life Sciences ISBN 978-3-319-91688-0 ISBN 978-3-319-91689-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91689-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018948152 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

Baker2009chap58.Pdf

Ratites and tinamous (Paleognathae) Allan J. Baker a,b,* and Sérgio L. Pereiraa the ratites (5). Here, we review the phylogenetic relation- aDepartment of Natural Histor y, Royal Ontario Museum, 100 Queen’s ships and divergence times of the extant clades of ratites, Park Crescent, Toronto, ON, Canada; bDepartment of Ecology and the extinct moas and the tinamous. Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada Longstanding debates about whether the paleognaths *To whom correspondence should be addressed (allanb@rom. are monophyletic or polyphyletic were not settled until on.ca) phylogenetic analyses were conducted on morphological characters (6–9), transferrins (10), chromosomes (11, 12), Abstract α-crystallin A sequences (13, 14), DNA–DNA hybrid- ization data (15, 16), and DNA sequences (e.g., 17–21). The Paleognathae is a monophyletic clade containing ~32 However, relationships among paleognaths are still not species and 12 genera of ratites and 46 species and nine resolved, with a recent morphological tree based on 2954 genera of tinamous. With the exception of nuclear genes, characters placing kiwis (Apterygidae) as the closest rela- there is strong molecular and morphological support for tives of the rest of the ratites (9), in agreement with other the close relationship of ratites and tinamous. Molecular morphological studies using smaller data sets ( 6–8, 22). time estimates with multiple fossil calibrations indicate that DNA sequence trees place kiwis in a derived clade with all six families originated in the Cretaceous (146–66 million the Emus and Cassowaries (Casuariiformes) (19–21, 23, years ago, Ma). The radiation of modern genera and species 24). -

PROGRAMME ABSTRACTS AGM Papers

The Palaeontological Association 63rd Annual Meeting 15th–21st December 2019 University of Valencia, Spain PROGRAMME ABSTRACTS AGM papers Palaeontological Association 6 ANNUAL MEETING ANNUAL MEETING Palaeontological Association 1 The Palaeontological Association 63rd Annual Meeting 15th–21st December 2019 University of Valencia The programme and abstracts for the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Palaeontological Association are provided after the following information and summary of the meeting. An easy-to-navigate pocket guide to the Meeting is also available to delegates. Venue The Annual Meeting will take place in the faculties of Philosophy and Philology on the Blasco Ibañez Campus of the University of Valencia. The Symposium will take place in the Salon Actos Manuel Sanchis Guarner in the Faculty of Philology. The main meeting will take place in this and a nearby lecture theatre (Salon Actos, Faculty of Philosophy). There is a Metro stop just a few metres from the campus that connects with the centre of the city in 5-10 minutes (Line 3-Facultats). Alternatively, the campus is a 20-25 minute walk from the ‘old town’. Registration Registration will be possible before and during the Symposium at the entrance to the Salon Actos in the Faculty of Philosophy. During the main meeting the registration desk will continue to be available in the Faculty of Philosophy. Oral Presentations All speakers (apart from the symposium speakers) have been allocated 15 minutes. It is therefore expected that you prepare to speak for no more than 12 minutes to allow time for questions and switching between presenters. We have a number of parallel sessions in nearby lecture theatres so timing will be especially important. -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

/ Chapter 2 THE FOSSIL RECORD OF BIRDS Storrs L. Olson Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC. I. Introduction 80 II. Archaeopteryx 85 III. Early Cretaceous Birds 87 IV. Hesperornithiformes 89 V. Ichthyornithiformes 91 VI. Other Mesozojc Birds 92 VII. Paleognathous Birds 96 A. The Problem of the Origins of Paleognathous Birds 96 B. The Fossil Record of Paleognathous Birds 104 VIII. The "Basal" Land Bird Assemblage 107 A. Opisthocomidae 109 B. Musophagidae 109 C. Cuculidae HO D. Falconidae HI E. Sagittariidae 112 F. Accipitridae 112 G. Pandionidae 114 H. Galliformes 114 1. Family Incertae Sedis Turnicidae 119 J. Columbiformes 119 K. Psittaciforines 120 L. Family Incertae Sedis Zygodactylidae 121 IX. The "Higher" Land Bird Assemblage 122 A. Coliiformes 124 B. Coraciiformes (Including Trogonidae and Galbulae) 124 C. Strigiformes 129 D. Caprimulgiformes 132 E. Apodiformes 134 F. Family Incertae Sedis Trochilidae 135 G. Order Incertae Sedis Bucerotiformes (Including Upupae) 136 H. Piciformes 138 I. Passeriformes 139 X. The Water Bird Assemblage 141 A. Gruiformes 142 B. Family Incertae Sedis Ardeidae 165 79 Avian Biology, Vol. Vlll ISBN 0-12-249408-3 80 STORES L. OLSON C. Family Incertae Sedis Podicipedidae 168 D. Charadriiformes 169 E. Anseriformes 186 F. Ciconiiformes 188 G. Pelecaniformes 192 H. Procellariiformes 208 I. Gaviiformes 212 J. Sphenisciformes 217 XI. Conclusion 217 References 218 I. Introduction Avian paleontology has long been a poor stepsister to its mammalian counterpart, a fact that may be attributed in some measure to an insufRcien- cy of qualified workers and to the absence in birds of heterodont teeth, on which the greater proportion of the fossil record of mammals is founded. -

New Oviraptorid Dinosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Nemegt Formation of Southwestern Mongolia

Bull. Natn. Sci. Mus., Tokyo, Ser. C, 30, pp. 95–130, December 22, 2004 New Oviraptorid Dinosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Nemegt Formation of Southwestern Mongolia Junchang Lü1, Yukimitsu Tomida2, Yoichi Azuma3, Zhiming Dong4 and Yuong-Nam Lee5 1 Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing 100037, China 2 National Science Museum, 3–23–1 Hyakunincho, Shinjukuku, Tokyo 169–0073, Japan 3 Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum, 51–11 Terao, Muroko, Katsuyama 911–8601, Japan 4 Institute of Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China 5 Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources, Geology & Geoinformation Division, 30 Gajeong-dong, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 305–350, South Korea Abstract Nemegtia barsboldi gen. et sp. nov. here described is a new oviraptorid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous (mid-Maastrichtian) Nemegt Formation of southwestern Mongolia. It differs from other oviraptorids in the skull having a well-developed crest, the anterior margin of which is nearly vertical, and the dorsal margin of the skull and the anterior margin of the crest form nearly 90°; the nasal process of the premaxilla being less exposed on the dorsal surface of the skull than those in other known oviraptorids; the length of the frontal being approximately one fourth that of the parietal along the midline of the skull. Phylogenetic analysis shows that Nemegtia barsboldi is more closely related to Citipati osmolskae than to any other oviraptorosaurs. Key words : Nemegt Basin, Mongolia, Nemegt Formation, Late Cretaceous, Oviraptorosauria, Nemegtia. dae, and Caudipterygidae (Barsbold, 1976; Stern- Introduction berg, 1940; Currie, 2000; Clark et al., 2001; Ji et Oviraptorosaurs are generally regarded as non- al., 1998; Zhou and Wang, 2000; Zhou et al., avian theropod dinosaurs (Osborn, 1924; Bars- 2000). -

A Multifunction Trade-Off Has Contrasting Effects on the Evolution of Form and Function ∗ KATHERINE A

Syst. Biol. 0():1–13, 2020 © The Author(s) 2020. Published by Oxford University Press, on behalf of the Society of Systematic Biologists. All rights reserved. For permissions, please email: [email protected] DOI:10.1093/sysbio/syaa091 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/sysbio/advance-article/doi/10.1093/sysbio/syaa091/6040745 by University of California, Davis user on 08 January 2021 A Multifunction Trade-Off has Contrasting Effects on the Evolution of Form and Function ∗ KATHERINE A. CORN ,CHRISTOPHER M. MARTINEZ,EDWARD D. BURRESS, AND PETER C. WAINWRIGHT Department of Evolution & Ecology, University of California, Davis, 2320 Storer Hall, 1 Shields Ave, Davis, CA, 95616 USA ∗ Correspondence to be sent to: University of California, Davis, 2320 Storer Hall, 1 Shields Ave, Davis, CA 95618, USA; E-mail: [email protected] Received 27 August 2020; reviews returned 14 November 2020; accepted 19 November 2020 Associate Editor: Benoit Dayrat Abstract.—Trade-offs caused by the use of an anatomical apparatus for more than one function are thought to be an important constraint on evolution. However, whether multifunctionality suppresses diversification of biomechanical systems is challenged by recent literature showing that traits more closely tied to trade-offs evolve more rapidly. We contrast the evolutionary dynamics of feeding mechanics and morphology between fishes that exclusively capture prey with suction and multifunctional species that augment this mechanism with biting behaviors to remove attached benthic prey. Diversification of feeding kinematic traits was, on average, over 13.5 times faster in suction feeders, consistent with constraint on biters due to mechanical trade-offs between biting and suction performance. -

Reidentification of Avian Embryonic Remains from the Cretaceous of Mongolia

RESEARCH ARTICLE Reidentification of Avian Embryonic Remains from the Cretaceous of Mongolia David J. Varricchio1*, Amy M. Balanoff2, Mark A. Norell3 1 Department of Earth Sciences, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana, 59717, United States of America, 2 Department of Anatomical Sciences, Stony Brook University School of Medicine, Stony Brook, NY, 11794, United States of America, 3 Division of Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, 10024, United States of America * [email protected] Abstract Embryonic remains within a small (4.75 by 2.23 cm) egg from the Late Cretaceous, Mongo- lia are here re-described. High-resolution X-ray computed tomography (HRCT) was used to digitally prepare and describe the enclosed embryonic bones. The egg, IGM (Mongolian In- stitute for Geology, Ulaanbaatar) 100/2010, with a three-part shell microstructure, was originally assigned to Neoceratopsia implying extensive homoplasy among eggshell char- acters across Dinosauria. Re-examination finds the forelimb significantly longer than the hindlimbs, proportions suggesting an avian identification. Additional, postcranial apomor- phies (strut-like coracoid, cranially located humeral condyles, olecranon fossa, slender radi- OPEN ACCESS us relative to the ulna, trochanteric crest on the femur, and ulna longer than the humerus) identify the embryo as avian. Presence of a dorsal coracoid fossa and a craniocaudally Citation: Varricchio DJ, Balanoff AM, Norell MA (2015) Reidentification of Avian Embryonic Remains compressed distal humerus with a strongly angled distal margin support a diagnosis of IGM from the Cretaceous of Mongolia. PLoS ONE 10(6): 100/2010 as an enantiornithine. Re-identification eliminates the implied homoplasy of this e0128458. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128458 tri-laminate eggshell structure, and instead associates enantiornithine birds with eggshell Academic Editor: Peter Dodson, University of microstructure composed of a mammillary, squamatic, and external zones.