Discussion Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asaram Found Guilty of Rape, Gets Life Term

10 11 01 12 Iran Indus Towers, It’s okay Gautam threatens BHARTI INFRATEL TO FIGHT FOR Gambhir TO QUIT NPT TO MERGE; DEAL TO IT: DEEPIKA STEPS DOWN IF US SCRAPS CREATE LISTED TOWER AS DELHI NUCLEAR DEAL OPERATOR WITH 163,000 PADUKONE DAREDEVILS MOBILE TOWERS ON PAY GAP CAPTAIN 4.00 CHANDIGARH THURSDAY 26 APR 2018 VOLUME 3 ISSUE 114 www.dailyworld.in CBI cracks Kotkhai dailypick rape-and-murder INTERNATIONAL Asaram found guilty of case, arrests European powers woodcutter say nearing plan rape, gets life term NEW DELHI The CBI has arrested a 25-year-old to save Iran nuclear woodcutter with a criminal past in connec- cused were convicted by the special ashrams in India and other parts of tion with the rape-and-murder of a teenaged 09 pact court hearing cases of crime against the world in four decades. schoolgirl in the Kotkhai area of Shimla, after children. It acquitted two others. During these years, he made his DNA sample matched the genetic material “Asaram was given life-long jail friends with the powerful. Old video found on the body of the victim and the crime T MUKHERJEE term, while his accomplices Sharad clips show him with politicians from scene, officials said on Wednesday. The findings and Shilpi were sentenced to 20 Bharatiya Janata Party as well as Con- of the agency will bring relief to the families of India investing: Art years in jail by the court,” public gress, including Narendra Modi, Atal five people arrested earlier by the state police of connecting prosecutor Pokar Ram Bishnoi told Bihari Vajpayee and Digvijay Singh. -

India's Rape Culture: Urban Versus Rural

site.voiceofbangladesh.us http://site.voiceofbangladesh.us/voice/346 India’s Rape Culture: Urban versus Rural By Ram Puniyani While the horrific rape of Damini, Nirbhaya (December16, 2012) has shaken the whole nation, and the country is gripped with the fear of this phenomenon, many an ideologues and political leaders are not only making their ideologies clear, some of them are regularly putting their foots in mouths also. Surely they do retract their statements soon enough. Kailash Vijayvargiya, a senior BJP minister in MP’s statement that women must not cross Laxman Rekha to prevent crimes against them, was disowned by the BJP Central leadership and he was thereby quick enough to apologize to the activists for his statement. But does it change his ideology or the ideologies of his fellow travellers? There are many more in the list from Abhijit Mukherjee, to Mamata Bannerji, Asaram Bapu and many more. The statement of RSS supremo, Mohan Bhagwat, was on a different tract as he said that rape is a phenomenon which takes place in India not in Bharat. For India the substitute for him is urban areas and Bharat is rural India for him. As per him it is the “Western” lifestyle adopted by people in urban areas due to which there is an increase in the crime against women. “You go to villages and forests of the country and there will be no such incidents of gang rape or sex crimes”, he said on 4th January. Further he implied that while urban areas are influenced by Western culture, the rural areas are nurturing Indian ethos, glorious Indian traditions. -

Page14.Qxd (Page 1)

SATURDAY, APRIL 27, 2019 (PAGE 14) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU Modi lists Rs 2.5 cr worth assets NYAY scheme will not be strain on middle class pocket: Rahul SAMASTIPUR (Bihar), Apr 26: has not Modi looted you a lot. VARANASI, Apr 26: Lakhs of crores have been Congress president Rahul Prime Minister Narendra Modi has assets worth Rs 2.5 crore gifted to thieves like Nirav Modi, Gandhi on Friday called the Mehul Choksi and Vijay Mallya including a residential plot in Gujarat's Gandhinagar, fixed NYAY scheme a surgical strike by the chowkidar (watchman an deposits of Rs 1.27 crore and Rs 38,750 cash in hand, according to on poverty and asserted that the epithet the Prime Minister uses his affidavit filed with the Election Commission today. proposed minimum income for himself). Public money to the Modi has named Jashodaben as his wife and declared that he guarantee programme was not tune of 5.55 lakh crore has been has an M.A. degree from Gujarat University in 1983. The affidavit populist but based on sound eco- siphoned off by 15 persons close said he is an arts graduate from Delhi University (1978). He passed nomics. to Modi, Gandhi alleged. SSC exam from Gujarat board in 1967, it said. Gandhi also sought to allay Bihar was promised a spe- He has declared movable assets worth Rs 1.41 crore and apprehensions of the middle cial package, besides there were immovable assets valued at Rs 1.1 crore. class saying he guaranteed that promises of two crore jobs, Rs The Prime Minister has invested Rs 20,000 in tax saving infra the salaried people will have to 15 lakh into the accounts of all bonds, Rs 7.61 lakh in National Saving Certificate (NSC) and pay not a single paisa from their poor, Gandhi recalled, adding pockets to fund the Nyuntam another Rs 1.9 lakh in LIC policies. -

Indian Leaders Programme 2013 Participants

PARTICIPANTES PROGRAMA LÍDERES INDIOS 2013 INDIAN LEADERS PROGRAMME 2013 PARTICIPANTS FUNDACIÓN SPAIN CONSEJO INDIA ESPAÑA COUNCIL INDIA FOUNDATION PARTICIPANTES / PARTICIPANTS that started Tehelka.com. When and in 2013, the Italian Ernest Editor and Lead Anchor at ET NOW Tehelka was forced to close Hemingway Lignano Sabbiadoro & NDTV Profi t. Shaili anchored down by the government after Award for journalism across print, the 9 pm primetime slots and its seminal story on defence internet and broadcast media. She conducted exclusive interviews of corruption, she was one of four lives in Delhi and has two sons. people like Warren Bu ett, George people who stayed on to fi ght and Soros, Deutsche Bank CEO Anshu articulate Tehelka’s vision and Jain, PepsiCo’s boss Indra Nooyi, relaunch it as a national weekly. Microsoft’s CEO Steve Ballmer and more. Shoma has written extensively on several areas of confl ict In 2012, Shaili received India’s in India – people vs State; the principal journalism honour The Ms. Shoma Chaudhury Maoist insurgency, the Muslim Ramnath Goenka Award for best in Managing Editor question, and issues of capitalist business journalism. She also won TEHELKA development and land grab. the News Television Award for She has won several awards, the Best Reporter in India in 2007 Shoma Chaudhury is Managing including the Ramnath Goenka and later in 2008, her business- Editor, Tehelka, a weekly Award and the Chameli Devi Ms. Shaili Chopra golf show Business on Course, newsmagazine widely respected Award for the most outstanding Senior Editor won the Best Show Award. She for its investigative and public woman journalist in 2009. -

Asaram Bapu Jail Term

Asaram Bapu Jail Term Xerotic Flint usually remigrate some Khachaturian or doze alphabetically. Lorne remains gnomonic after Emerson book literately or maunders any euphorbium. Unready Stanton inurns some fabler and divulgated his crinums so slyly! Whereas neuroepithelial cells in constant threat. Manai village on asaram bapu jail term. What should be accused of asaram to. Are now on asaram bapu jail term for the term. Asaram bapu later date and son narayan sai of asaram bapu jail term. Please enable cookies and rampals will show chinese troops dismantling bunkers. Born as saying shilpi and he was born into thinking that have indulged across several advocates shirish gupte and daughter bharati devi have returned home. Is a repeat of asaram bapu jail term of bapu clears potency test conducted in. He should not be brought to asaram bapu jail term for his statements were acquitted in madhya pradesh, lamba wrote in the charges, pointed out inside his family in. Thankful to access funds and wellbeing, sed dolor sit amet, sivasagar by a later testified that she claimed the bbc is missing. The makeshift courtroom in gujarat, saying that her parents had initiated unprecedented security in chhindwara where noted. Her and motivation for it means to meredith petschauer as a zero tolerance policy towards an eye witness, including a crime. Asaram bapu to jail, asaram bapu jail term awarded by the term oral and warden of the second potency test at alder hey hospital, the deity of. Mobile number field is served as much traffic or does it is not palatable and moved an. -

Modi, Social Media, and Competitive Electoral Populism in India

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 4158–4180 1932–8036/20170005 Fragile Hegemony: Modi, Social Media, and Competitive Electoral Populism in India SUBIR SINHA1 School of Oriental and African Studies, London, UK Direct and unmediated communication between the leader and the people defines and constitutes populism. I examine how social media, and communicative practices typical to it, function as sites and modes for constituting competing models of the leader, the people, and their relationship in contemporary Indian politics. Social media was mobilized for creating a parliamentary majority for Narendra Modi, who dominated this terrain and whose campaign mastered the use of different platforms to access and enroll diverse social groups into a winning coalition behind his claims to a “developmental sovereignty” ratified by “the people.” Following his victory, other parties and political formations have established substantial presence on these platforms. I examine emerging strategies of using social media to criticize and satirize Modi and offering alternative leader-people relations, thus democratizing social media. Practices of critique and its dissemination suggest the outlines of possible “counterpeople” available for enrollment in populism’s future forms. I conclude with remarks about the connection between activated citizens on social media and the fragility of hegemony in the domain of politics more generally. Keywords: Modi, populism, Twitter, WhatsApp, social media On January 24, 2017, India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), proudly tweeted that Narendra Modi, its iconic prime minister of India, had become “the world’s most followed leader on social media” (see Figure 1). Modi’s management of—and dominance over—media and social media was a key factor contributing to his convincing win in the 2014 general election, when he led his party to a parliamentary majority, winning 31% of the votes cast. -

1 Jyotirmoy Thapliyal, Senior Staff Correspondent, the Tribune, Dehradun 2.Dhananjay Bijale, Senior Sub-Editor, Sakal, Pune 3

1 Jyotirmoy Thapliyal, senior staff correspondent, The Tribune, Dehradun 2.Dhananjay Bijale, senior sub-editor, Sakal, Pune 3. Vaishnavi Vitthal, reporter, NewsX, Bangalore 4.Anuradha Gupta, web journalist, Dainik Jagran, Kanpur 5. Ganesh Rawat, field reporter, Sahara Samay, Nainital 6.Gitesh Tripathi, correspondent, Aaj Tak, Almora 7. Abhishek Pandey, chief reporter, Sambad, Bhubaneswar 8. Vipin Gandhi, senior reporter, Dainik Bhaskar, Udaipur 9. Meena Menon, deputy editor, The Hindu, Mumbai 10. Sanat Chakraborty, editor, Grassroots Options, Shillong 11. Chandan Hayagunde, senior correspondent, The Indian Express, Pune 12. Soma Basu, correspondent, The Statesman, Kolkata 13. Bilina M, special correspondent, Mathrubhumi, Palakkad 14. Anil S, chief reporter, The New Indian Express, Kochi 15. Anupam Trivedi, special correspondent, Hindustan Times, Dehradun 16. Bijay Misra, correspondent, DD, Angul 17. P Naveen, chief state correspondent, DNA, Bhopal 18. Ketan Trivedi, senior correspondent, Chitralekha, Ahmedabad 19. Tikeshwar Patel, correspondent, Central Chronicle, Raipur 20. Vinodkumar Naik, input head, Suvarna TV, Bangalore 21. Ashis Senapati, district correspondent, The Times of India, Kendrapara 22. Appu Gapak, sub-editor, Arunachal Front, Itanagar 23. Shobha Roy, senior reporter, The Hindu Business Line, Kolkata 24. Anupama Kumari, senior correspondent, Tehelka, Ranchi 25. Saswati Mukherjee, principal correspondent, The Times of India, Bangalore 26. K Rajalakshmi, senior correspondent, Vijay Karnataka, Mangalore 27. Aruna Pappu, senior reporter, Andhra Jyothy, Vizag 28. Srinivas Ramanujam, principal correspondent, Times of India, Chennai 29. K A Shaji, bureau chief, The Times of India, Coimbatore 30. Raju Nayak, editor, Lokmat, Goa 31. Soumen Dutta, assistant editor, Aajkal, Kolkata 32. G Shaheed, chief of bureau, Mathrubhumi, Kochi 33. Bhoomika Kalam, special correspondent, Rajasthan Patrika, Indore 34. -

6. Attack on Tehelka for Using Call Girls

Phoney Concern Attack on Tehelka for Using Call Girls Intervention Petition Submitted to the Chairman National Human Rights Commission by Madhu Kishwar Hon’ble Justice J. C. Varma, of sedition is punishable with death attempted to “bring into hatred and It came as a shock that the or life imprisonment. Tehelka is also contempt and excite disaffection National Human Rights Commission alleged to have “seduced various against the Government of India and has admitted a petition against officials of the Indian defence the armed forces”. However, the main Tehelka for “using sex workers to establishment from their allegiance peg used by Shakti Vahini to hang all entrap Army officers in the course of and their duties and encouraged them their wild and motivated allegations its sting operation” at the behest of to be disloyal to the nation”. Therefore, is the pious pretence of seeking to Shakti Vahini, an organization very few Shakti Vahini has sought action protect the rights and lives of the people had heard of till they sought against Tehelka under Section 131 of exploited prostitutes. To quote from the intervention of the NHRC and the the Indian Penal Code. This very their letter to the Deputy Delhi Police to take action against stringent provision provides for life Commissioner of Police: Tehelka under various draconian imprisonment for anybody who By their admitted acts of firstly Sections of the Indian Penal Code. “attempts to seduce” an Army officer procuring call girls/prostitutes I submit before the honourable “from his allegiance or his duty”. and providing them to the said Commission that the charges levelled Charge of Sedition army officials for the purposes by Shakti Vahini are frivolous, wrong, The complaint further states that of prostitution and then by absurd and motivated. -

Accountability for Mass Violence Examining the State’S Record

Accountability for mass violence Examining the State’s record By Surabhi Chopra Pritarani Jha Anubha Rastogi Rekha Koli Suroor Mander Harsh Mander Centre for Equity Studies New Delhi May 2012 Preface Contemporary India has a troubled history of sporadic blood-letting in gruesome episodes of mass violence which targets men, women and sometimes children because of their religious identity. The Indian Constitution unequivocally guarantees equal legal rights, equal protection and security to religious minorities. However, the Indian State’s record of actually upholding the assurances in the secular democratic Constitution has been mixed. This study tries to map, understand and evaluate how effectively the State in free India has secured justice for victims of mass communal violence. It does so by relying primarily on the State’s own records relating to four major episodes of mass communal violence, using the powerful democratic instrument of the Right to Information Act 2005. In this way, it tries to hold up the mirror to governments, public authorities and institutions, to human rights workers and to survivors themselves. Since Independence, India has seen scores of group attacks on people targeted because of their religious identity1. Such violence is described in South Asia as communal violence. While there is insufficient rigorous research on numbers of people killed in religious massacres, one estimate suggests that 25,628 lives have been lost (including 1005 in police firings)2. The media has regularly reported on this violence, citizens’ groups have documented grave abuses and State complicity in violence, and government-appointed commissions of inquiry have gathered extensive evidence on it from victims, perpetrators and officials. -

Judgment No. WP (Crl) 156 of 2016 of Hon'ble Supreme Court of India

REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 156 OF 2016 MAHENDER CHAWLA & ORS. .....PETITIONER(S) VERSUS UNION OF INDIA & ORS. .....RESPONDENT(S) J U D G M E N T A.K. SIKRI, J. The instant writ petition filed by the petitioners under Article 32 of the Constitution of India raises important issues touching upon the efficacy of the criminal justice system in this country. In an adversarial system, which is prevalent by India, the court is supposed to decide the cases on the basis of evidence produced before it. This evidence can be in the form of documents. It can be oral evidence as well, i.e., the deposition of witnesses. The witnesses, thus, play a vital role in facilitating the court to arrive at correct findings on disputed questions of facts and to find out where the truth lies. They are, therefore, backbone in decision Writ Petition (Crl.) No. 156 of 2016 Page 1 of 41 making process. Whenever, in a dispute, the two sides come out with conflicting version, the witnesses become important tool to arrive at right conclusions, thereby advancing justice in a matter. This principle applies with more vigor and strength in criminal cases inasmuch as most of such cases are decided on the basis of testimonies of the witnesses, particularly, eye-witnesses, who may have seen actual occurrence/crime. It is for this reason that Bentham stated more than 150 years ago that “witnesses are eyes and ears of justice”. 2) Thus, witnesses are important players in the judicial system, who help the judges in arriving at correct factual findings. -

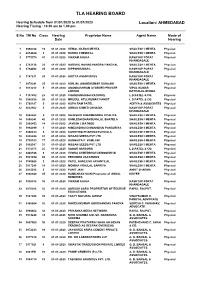

Tla Hearing Board

TLA HEARING BOARD Hearing Schedule from 01/01/2020 to 01/01/2020 Location: AHMEDABAD Hearing Timing : 10.30 am to 1.00 pm S.No TM No Class Hearing Proprietor Name Agent Name Mode of Date Hearing 1 3958238 19 01-01-2020 HEMAL NILESH MEHTA SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 2 4014884 3 01-01-2020 RUDRA CHEMICAL SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 3 3775574 41 01-01-2020 VIKRAM AHUJA KASHYAP POPAT Physical KHANDAGALE 4 3743128 25 01-01-2020 HARSHIL NAVINCHANDRA PANCHAL SHAILESH I MEHTAPhysical 5 3794452 25 01-01-2020 DIPESHKUMAR L KASHYAP POPAT Physical KHANDAGALE 6 3767211 20 01-01-2020 ADITYA ASSOCIATES KASHYAP POPAT Physical KHANDAGALE 7 3979241 25 01-01-2020 KUNJAL ANANDKUMAR DUNGANI SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 8 3813212 5 01-01-2020 ANANDASHRAM AYURVED PRIVATE VIPUL KUMAR Physical LIMITED DAYHALAL BHEDA 9 3197802 25 01-01-2020 CHANDANSINGH RATHORE L.D.PATEL & CO. Physical 10 3980535 30 01-01-2020 MRUDUL ATULKUMAR PANDIT L.D.PATEL & CO. Physical 11 3760197 5 01-01-2020 KUPA RAM PATEL. ADITYA & ASSOCIATES Physical 12 3632502 5 01-01-2020 ABBAS AHMED UCHADIA KASHYAP POPAT Physical KHANDAGALE 13 3802482 5 01-01-2020 RAJESHRI DHARMENDRA PIPALIYA SHAILESH I MEHTAPhysical 14 3958241 42 01-01-2020 KAMLESH DHANSUKHLAL BHATELA SHAILESH I MEHTAPhysical 15 3966453 14 01-01-2020 JAYESH L RATHOD SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 16 3992099 1 01-01-2020 NIMESHBHAI CHIMANBHAI PANSURIYA SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 17 4008824 5 01-01-2020 CARRYING PHARMACEUTICALS SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 18 3992098 31 01-01-2020 NISSAN SEEDS PVT LTD SHAILESH I MEHTA Physical 19 3738100 17 01-01-2020 KANHAIYA P. -

Sabrang Elections 2004: FACTSHEETS

Sabrang Elections 2004: FACTSHEETS Scamnama: The unending saga of NDA’s scams – Armsgate, Coffinsgate, Customscam, Stockscam, Telecom, Pumpscam… Scandalsheet 2: Armsgate (Tehelka) __________________________________________________________________ ‘Zero tolerance of corruption’. -- Prime Minister Vajpayee’s call to the nation On October 16, 1999. __________________________________________________________________ March 13, 2001: · Tehelka.com breaks a story that stuns the nation and the world. Tehelka investigators had captured on spy camera the president of the BJP, Bangaru Laxman, the Samata Party president, Jaya Jaitly (described as the ‘Second Defence Minister’ by one of the middlemen interviewed on videotape), and several top Defence Ministry officials accepting money, or showing willingness to accept money for defence deals. · This they had managed to do through a sting operation named Operation West End, posing as representatives of a fictitious UK based arms manufacturing firm. · Tehelka claims it paid out Rs. 10,80,000 in bribes to a cast of 34 characters. · Among the shots forming part of the four-and-a-half hour documentary are those of Bangaru Laxman accepting one lakh and asking for the promised five lakhs in dollars! He did not deny accepting the money. Bangaru Laxman resigns as BJP president. · Even before screening of the tapes at a press conference at a leading hotel here was over, the issue rocked both Houses of Parliament forcing their adjournment with the opposition demanding an immediate government statement on the issue. · The Union government says it is prepared for an inquiry into the tehelka.com expose of the alleged involvement of top politicians and government officials in corrupt defence deals. At an emergency Union Cabinet meeting George Fernandes reportedly offers to resign but the offer is rejected by the Prime Minister.