AN INDEPENDENT REPORT to INFORM the UK NATIONAL SHIPBUILDING STRATEGY by SIR JOHN PARKER GBE Freng

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delivering a Marine Technology Hub for Scotland White Paper

Delivering a Marine Technology Hub for Scotland White Paper Ref: MG/DMTHS/WP004 Rev 00 December 2020 White paper Malin Group Malin Group White paper Contents Page “To innovatively create new sustainable high quality, green jobs in the Scottish Maritime Manufacturing and 1 Executive summary Page 3 Technology Sector and deliver wealth creation into the New, high value, green jobs in the marine local communities of the Clyde.” Page 5 2 sector Scottish Marine Technology Park Mission The role of the public sector in a Scottish Page 7 2.1 maritime renaissance 2.2 Ferries Page 9 Oil and gas, defence and commercial 2.3 Page 11 marine opportunities 2.4 Renewables Page 12 2.5 Green shipping technology Page 13 Supporting an environmentally sustainable 2.6 Page 15 Scotland 3 Delivering local community wealth building Page 17 4 Attracting new business to Scotland Page 18 Scotland leading a smarter approach to 5 Page 19 marine manufacturing Incubate our marine innovators to create Page 21 6 viable businesses 7 Conclusion Page 22 2 White paper Malin Group Malin Group White paper Executive summary The Scottish economy will, like many others, face immense challenges as we seek to repair the damage caused to businesses, Malin Group are marine engineers – not property developers. By securing ownership of the Old Kilpatrick site we have created industries and employment by the Coronavirus pandemic. As in all periods of crisis, however, changed circumstances also create the opportunity to develop the Scottish Marine Technology Park. However beyond the area required for our own company’s use, new opportunities and demand reappraisal of past assumptions to deliver an exciting, prosperous future for Scotland. -

C R S C Scottish Ferry News NOVEMBER 2014

CRSC – Scottish Ferry News 01.10.14 – 11.11.14 CalMac Ferries Ltd: Argyle Wemyss Bay – Rothesay rosters. T 21 Oct stormbound at Rothesay from 1135; Su 26 diverted to Gourock; T 28 off service p.m. (tech, Coruisk on roster); W 29 resumed service. Bute Wemyss Bay – Rothesay rosters. T 7 Oct off service (tech); F 10 resumed roster at 0930; T 21 stormbound at Rothesay from 1050; Su 26 sailings diverted to Gourock after first run; T 28 to Garvel JWD after last run; W 29 drydocked (with Lord of the Isles) for annual survey. Brigadoon Chartered from Brigadoon Boat Trips for Raasay – Sconser service F 17 & S 18 Oct (passenger-only). Caledonian Isles Ardrossan – Brodick roster. Th 2, Su 5, S 18, M 20, S 25, Su 26 & M 27 Oct berthed overnight at Brodick (weather); T 21 stormbound all day at Brodick; Su 26 1640/1800 sailing only (weather). Th 6 Nov diverted to Gourock. Clansman Oban – Coll – Tiree/Barra – S Uist roster. Th 2 Oct only sailed Oban – Coll – Tiree – Oban (weather); Su 5 1540 Outer Isles cancelled (weather, berthed NLB Pier); M 6 resumed roster 1540; T 21 stormbound at Castlebay; W 22 to Lochboisdale and Oban; Th 23 resumed roster; S 25 Castlebay cancelled (weather); Su 26 stormbound at Oban, 1540 Outer Isles sailing delayed until 0600/M 27 ( Isle of Mull took delayed 1600/1700 Craignure); T 28 resumed combined winter Inner/Outer Isles roster (in force till S 29 Nov, incl. Craignure M+W). S 1 Nov roster amended for Tiree livestock sales, additional second run cancelled (weather); M 3 + Tiree inward; T 4 – F 7 Outer Isles roster amended (tidal); Th 6 Inner Isles cancelled (weather). -

LDP2 As-Modified June2019.Pdf

FOREWORD Welcome to the Inverclyde Local Development Plan. The aim of the Plan is to contribute towards Inverclyde being an attractive and inclusive place to live, work, study, visit and invest. It does this through encouraging investment and new development, which is sustainably designed and located and contributes to the creation of successful places. The Council and its community planning partners in the Inverclyde Alliance have established, through the Inverclyde Outcomes Improvement Plan, three priorities for making Inverclyde a successful place. These are repopulation, reducing inequalities, and environment, culture and heritage, which are all supported by the Local Development Plan. To address repopulation, the Outcomes Improvement Plan recognises employment and housing opportunities as crucial. The Local Development Plan responds by identifying land for over 5000 new houses and over 20 hectares of land for new industrial and business development. Repopulation will also be driven by enhancing the image of Inverclyde and the Plan includes proposals for our larger regeneration sites, which we refer to as Priority Places, policies to support our town and local centres, and sets a requirement for all new development to contribute towards creating successful places. In response to the environment, culture and heritage priority, the Plan continues to protect our historic buildings and places, and our natural and open spaces. These include the Inner Clyde and Renfrewshire Heights Special Protection Areas, 7 Sites of Special Scientific Interest, 57 Local Nature Conservation Sites, 8 Conservation Areas, 247 Listed Buildings, 31 Scheduled Monuments and 3 Gardens and Designed Landscapes. Collectively, these natural and historic assets demonstrate the natural and cultural richness and diversity of Inverclyde. -

SB-4207-January-NA.Pdf

Scottishthethethethe www.scottishbanner.com Banner 37 Years StrongScottishScottishScottish - 1976-2013 Banner A’BannerBanner Bhratach Albannach 42 Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Years Strong - 1976-2018 www.scottishbanner.com A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 42 36 36 NumberNumber Number 711 11 TheThe The world’s world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international ScottishScottish Scottish newspaper newspaper May January May 2013 2013 2019 Up Helly Aa Lighting up Shetland’s dark winter with Viking fun » Pg 16 2019 - A Year in Piping » Pg 19 US Barcodes A Literary Inn ............................ » Pg 8 The Bards Discover Scotland’s Starry Nights ................................ » Pg 9 Scotland: What’s New for 2019 ............................. » Pg 12 Family 7 25286 844598 0 1 The Immortal Memory ........ » Pg 29 » Pg 25 7 25286 844598 0 9 7 25286 844598 0 3 7 25286 844598 1 1 7 25286 844598 1 2 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Volume 42 - Number 7 Scottishthe Banner The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Offices of publication Valerie Cairney Australasian Office: PO Box 6202 Editor Marrickville South, Starting the year Sean Cairney NSW, 2204 Tel:(02) 9559-6348 EDITORIAL STAFF Jim Stoddart [email protected] Ron Dempsey, FSA Scot The National Piping Centre North American Office: off Scottish style PO Box 6880 David McVey Cathedral you were a Doonie, with From Scotland to the world, Burns Angus Whitson Hudson, FL 34674 Lady Fiona MacGregor [email protected] Uppies being those born to the south, Suppers will celebrate this great Eric Bryan or you play on the side that your literary figure from Africa to America. -

Construction and Procurement of Ferry Vessels in Scotland DRAFT DRAFT

Published 9 December 2020 SP Paper 879 12th Report, 2020 (Session 5) Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee Comataidh Eaconomaidh Dùthchail is Co- cheangailteachd Construction and procurement of ferry vessels in Scotland DRAFT DRAFT Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. All documents are available on the Scottish For information on the Scottish Parliament contact Parliament website at: Public Information on: http://www.parliament.scot/abouttheparliament/ Telephone: 0131 348 5000 91279.aspx Textphone: 0800 092 7100 Email: [email protected] © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliament Corporate Body The Scottish Parliament's copyright policy can be found on the website — www.parliament.scot Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee Construction and procurement of ferry vessels in Scotland, 12th Report, 2020 (Session 5) Contents Summary of conclusions and recommendations _____________________________1 Introduction ___________________________________________________________13 Background ___________________________________________________________15 Hybrid ferries contract: the procurement process____________________________20 Ferguson Marine capabilities_____________________________________________29 Management of hybrid ferries contract _____________________________________31 Design specification and design process issues ______________________________31 Community and other stakeholder views on vessel design ____________________36 Delays and cost overruns _______________________________________________40 -

Turning the Tide Rebuilding the UK’S Defence Shipbuilding Industry and the Fleet Solid Support Order CAMPAIGNING for MANUFACTURING JOBS

CAMPAIGNING FOR MANUFACTURING JOBS Turning the Tide Rebuilding the UK’s defence shipbuilding industry and the Fleet Solid Support Order CAMPAIGNING FOR MANUFACTURING JOBS A Making It Report Written by: Laurence Turner, Research and Policy Offer, GMB Photographs on this page, page 10, 19 and 38 are published courtesy of BAE Systems. The pictures depict the QE Carrier, Type 26 and River-class Offshore Patrol Vessel ships which were built by GMB members. All other images used are our own. The picture opposite shows GMB shipbuilding reps meeting MPs and Shadow Ministers in Parliament to discuss this reoprt. Some images in this report are reproduced from a mural commissioned by the Amalgamated Society of Boilermakers, Shipwrights, Blacksmiths and Structural Workers. The mural commemorates GMB’s proud history in shipbuilding and other engineering occupations. Artist: John Warren. A GMB Making It report 1 Contents FOREWORD CAMPAIGNING FOR MANUFACTURING JOBS British shipbuilding is at a crossroads. Executive Summary 3 History 4 As the aircraft carrier programme winds down, there is real uncertainty over the future of the industry. The Government says that it wants to see a shipbuilding ‘renaissance’ but it has not The Royal Fleet Auxiliary and the Fleet Solid Support order 6 introduced the policies that would achieve this aim. Shipbuilding manufacturing is as much a part of our sovereign defence capability as the The RFA 6 warships and submarines that it produces. British yards can still build first class fighting and support ships: the Type 45 destroyer is the envy of the world. We are proud that it was made by Government shipbuilding procurement policy 6 GMB members. -

CANAL SAFETY CRISIS Royal Fleet Auxiliary Service

INDUSTRY WELFARE NL NEWS MN IN WARTIME Why Stena's new Irish The social media training Nautilus NL 'Stronger First-hand account of Sea ferry is something that seeks to improve together' recruitment Arctic seafaring in the of a mixed blessing seafarers' mental health campaign picks up pace First World War Volume 53 | Number 2 | February 2020 | £5 €5.90 CANAL SAFETY CRISIS Royal Fleet Auxiliary Service Opportunities exist for Marine Engineering Officers Officer of the Watch, Second Engineer or Chief Engineer CoC with HND/Foundation Degree in Marine Engineering Systems Engineering Officers/ Electro-Technical Officers You’ll need a Degree or HND in Electrical and Electronic Engineering or an STCW A-lll/6 ETO Certificate of Competency with recent seagoing experience. All candidates must hold STCW 2010 Manila Amendments Update Training and a current ENG1 certificate. Benefits include • Competitive Annual Salaries • Paid Voyage Leave • Competitive Civil Service Pension Scheme • Industry-leading fully funded Study Leave Programme • World Class Comprehensive Training Programme • 100% UK Registered Seafarers • Diverse and Inclusive employer • IMarEst accredited training provider royalnavy.mod.uk/careers/rfa [email protected] 02392 725960 Editor’s CONTENTS letter Volume 53 | Number 2 | February 2020 Just before Christmas, Nautilus was contacted by our Federation partners, a union for tug captains on the Panama Canal known as Unión de telegraph Capitanes y Oficiales de Cubierta (UCOC). It was concerned for 13 Union activists who were either suspended or part suspended without pay by the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) COMMENT for speaking up about safety fears brought 12 on by fatigue-inducing work patterns at the 05 General secretary Mark Dickinson expanded Canal. -

Monday 5 July 2021 Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean

Monday 5 July 2021 Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean Change to membership of the Parliamentary Bureau The Presiding Officer wishes to inform Members that Gillian Mackay has replaced Patrick Harvie as the representative for the Scottish Green Party on the Parliamentary Bureau. Today's Business Meeting of the Parliament Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. There are no meetings today. Monday 5 July 2021 1 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Meeting of the Parliament There are no meetings today. Monday 5 July 2021 2 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Committees | Comataidhean Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. Monday 5 July 2021 3 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Future Meetings of the Parliament Business Programme agreed by the Parliament on 23 June 2021 Tuesday 31 August 2021 2:00 pm Time for Reflection followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions followed by Topical Questions (if selected) followed by First Minister’s Statement: Programme for Government 2021-22 followed by Committee Announcements followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions 5:00 pm Decision Time followed by Members' Business Wednesday 1 -

Scot Pourri Looking to Find Family Connections Castles & “Durty” Wee Rascals the Clydebank Blitz Send Us Your Inquiries on Life’S Little Question Marks

The ScoTTiSh Banner SCOT POURRI Looking to find family connections Castles & “Durty” Wee Rascals The Clydebank Blitz Send us your inquiries on life’s little question marks. Ever wanted to know what Ms.Voilet Milne McIntyre of Niagara Falls, I enjoy Jim Stoddart’s articles as I come from happened to your old pal from home, how NY, 92 years young. Wrote with a request “Doon the Watter” at Port Glasgow. I went to make your favourite Scottish meal, or concerning a member of her family. to Glasgow University in 1950, just in time wondered about a certain bit of Scottish Her father James Milne of Montrose for the 500 years celebrations and always history? Pose your questions on Scottish who served in the 10th Battalion of the dressed up for student charity days, going by related topics to our knowledgeable Canadian Infantry had a nephew Capt. train to Glasgow. I totally identified with Jim’s readership who just may be able to help. Our Edward R. Milne late of Montrose, Angus piece about old customs, including having letters page is a very popular and active one shire who was in the 10th Battalion of the clean underwear in case of an accident, wear and many readers have been assisted across Canadian Infantry in the first world war. the world by fellow passionate Scots. Please green wear black was a thing of my mother’s His untimely death came about when keep letters under 200 words and we reserve and I didn’t own anything green until after the right to edit content and length. -

Publication Scheme – Guide to Information Ferguson Marine (Port Glasgow) Limited

FOI PUBLICATION SCHEME PUBLICATION SCHEME – GUIDE TO INFORMATION FERGUSON MARINE (PORT GLASGOW) LIMITED 1 CONTENTS 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Purpose………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 1.2 Availability and Formats.......................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Exempt Information ................................................................................................................ 3 1.4 Copyright ................................................................................................................................. 4 1.5 Fees ......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.6 Advice and Assistant – Contact Detaiks .................................................................................. 5 1.7 Duration .................................................................................................................................. 5 2. The classes of information that we publish ................................................................................ 6 2.1 Class 1 – About Us ................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Class 2 – How we deliver our functions and services ............................................................. 6 2.3 -

UPDATE on PROGRESS and IMPACT of COVID-19 on PROGRAMME for VESSELS 801 & 802 ISSUED 21ST August 2020

UPDATE ON PROGRESS AND IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON PROGRAMME FOR VESSELS 801 & 802 ISSUED 21ST August 2020 Issued By: Tim Hair 21st August 2020 Turnaround Director Signature TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Summary ............................................................................................................................. 1 2 Update ................................................................................................................................ 1 2.1 Re-energising of a demoralised workforce and the improvement of productivity .... 2 2.2 Ability to attract the right talent and resource with sufficiently competent people .2 2.3 Ability to put in place and operate the new processes required ................................ 3 2.4 Impact of future as yet unidentified rework to the project ........................................ 3 2.5 Control and management of the design subcontractor ............................................. 4 2.6 Public Procurement ..................................................................................................... 4 3 COVID-19 Lockdown ........................................................................................................... 4 4 Assumptions ....................................................................................................................... 5 4.1 Timetable..................................................................................................................... 5 4.2 Cost ............................................................................................................................. -

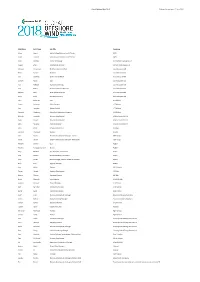

Delegate List 150618.Xlsm

Global Offshore Wind 2018 Delegate list generated 15 June 2018 First Name Last Name Job Title Company Olivier Houet Work Package Electrical and ICT Scada 1973 Hervé Lavirotte Work Package Electrical and ICT Scada 1973 Gilles Gardner Technical Manager 2H Offshore Engineering Ltd Kangjie Zhao Development Director 3d Web Technologies LTD Christian Christensen Chief Development Officer 3sun Group Limited Glenn Cooper Chairman 3sun Group Limited Sam Copeman Chief Financial Officer 3sun Group Limited Graham Hacon CEO 3sun Group Limited Paul Hubbard Deployment Manager 3sun Group Limited Jody Potter Senior Key Account Manager 3sun Group Limited Stephen Rose Chief Operating Officer 3sun Group Limited Sherri Smith Company Secretary 3sun Group Limited Chris Anderson CEO 4C Offshore Lauren Anderson Sales Manager 4C Offshore Sam Langston Market Analyst 4C Offshore Vincenzo Poidomani Consultant Geotechnical Engineer 4C Offshore Miranda Carpenter Business Development 6 Alpha Associates Ltd Angus Cooper Business Development 6 Alpha Associates Ltd Mark Daubney General Manager 6 Alpha Associates Ltd Chris Smith Senior Client Partner 6 Group Cameron Thompson Student A Level Chris Davies Business Development Manager ‐ Marine A&P Group Emma Harrick Business Development Manager‐ Renewables A&P Group Michael Glavind CEO A2SEA Nicoline Kousgaard Laursen Barista A2SEA Tony Millward Vice President, Commercial A2SEA Gina Nielsen Senior Marketing Coordinator A2SEA Klaus Nissen Senior Manager, Head of Tenders & Contracts A2SEA Andy Reay Regional Manager A2SEA John