TEACHINGS of the BOOK of MORMON HUGH NIBLEY Semester 2, Lecture 31 Mosiah 7 Stable Civilizations the Search for the Lost Colony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events Earl M. Wunderli DURING THE PAST FEW DECADES, a number of LDS scholars have developed various "limited geography" models of where the events of the Book of Mormon occurred. These models contrast with the traditional western hemisphere model, which is still the most familiar to Book of Mormon readers. Of the various models, the only one to have gained a following is that of John Sorenson, now emeritus professor of anthropology at Brigham Young University. His model puts all the events of the Book of Mormon essentially into southern Mexico and southern Guatemala with the Isthmus of Tehuantepec as the "narrow neck" described in the LDS scripture.1 Under this model, the Jaredites and Nephites/Lamanites were relatively small colonies living concurrently with other peoples in- habiting the rest of the hemisphere. Scholars have challenged Sorenson's model based on archaeological and other external evidence, but lay people like me are caught in the crossfire between the experts.2 We, however, can examine Sorenson's model based on what the Book of Mormon itself says. One advantage of 1. John L. Sorenson, "Digging into the Book of Mormon," Ensign, September 1984, 26- 37; October 1984, 12-23, reprinted by the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS); An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: De- seret Book Company, and Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1985); The Geography of Book of Mormon Events: A Source Book (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1990); "The Book of Mormon as a Mesoameri- can Record," in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited, ed. -

L17 a Seer … Becometh a Great Benefit to His Fellow Beings.Pages

Lesson 17: “A Seer … Becometh a Great Benefit to His Fellow Beings” (Mos. 7–11) L17 Study Guide Purpose: To encourage us to follow the counsel of Church leaders, particularly our prophets, seers, and revelators” See the diagram and explanation of the Land of Lehi-Nephi. 1. Ammon and his brethren find Limhi and his people. Ammon teaches Limhi of the importance of a seer. (Mosiah 7-8.) • Mos. 7:7-11 Ammon and his15 cohorts are taken captive by King Limhi’s guards. • Mos. 7:12-15 Ammon tells his story and King Limhi rejoices. • Mos. 7:17-20, 29-33 What principles does King Limhi teach his people? What does this tell us about King Limhi? • Mos. 8:7 King Limhi reports that he had sent out a scouting part of 43 persons to find Zarahemla. • Mos. 8:8-12 They found 24 gold plates and King Limhi desires they be translated. Why would it be helpful for Limhi’s people, and us, to “know the cause of [the] destruction” of the Jaredites? • Mosiah 8:13-16 Ammon told Limhi of a king who was a prophet and seer. • Mosiah 8:13, 17-18 How do prophets, seers, and revelators fulfill these roles? How have latter-day prophets, seers, and revelators been “a great benefit” to you? †1. Elder Boyd K. Packer †2. Elder John A. Widstoe 2. The record of Zeniff recounts a brief history of Zeniff’s people. (Mosiah 9-10.) Chapters 9 through 22 “of the book of Mosiah contain a history of the people who left Zarahemla to return to the land of Nephi. -

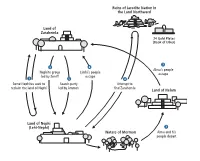

Land of Zarahemla Land of Nephi (Lehi-Nephi) Waters of Mormon

APPENDIX Overview of Journeys in Mosiah 7–24 1 Some Nephites seek to reclaim the land of Nephi. 4 Attempt to fi nd Zarahemla: Limhi sends a group to fi nd They fi ght amongst themselves, and the survivors return to Zarahemla and get help. The group discovers the ruins of Zarahemla. Zeniff is a part of this group. (See Omni 1:27–28 ; a destroyed nation and 24 gold plates. (See Mosiah 8:7–9 ; Mosiah 9:1–2 .) 21:25–27 .) 2 Nephite group led by Zeniff settles among the Lamanites 5 Search party led by Ammon journeys from Zarahemla to in the land of Nephi (see Omni 1:29–30 ; Mosiah 9:3–5 ). fi nd the descendants of those who had gone to the land of Nephi (see Mosiah 7:1–6 ; 21:22–24 ). After Zeniff died, his son Noah reigned in wickedness. Abinadi warned the people to repent. Alma obeyed Abinadi’s message 6 Limhi’s people escape from bondage and are led by Ammon and taught it to others near the Waters of Mormon. (See back to Zarahemla (see Mosiah 22:10–13 ). Mosiah 11–18 .) The Lamanites sent an army after Limhi and his people. After 3 Alma and his people depart from King Noah and travel becoming lost in the wilderness, the army discovered Alma to the land of Helam (see Mosiah 18:4–5, 32–35 ; 23:1–5, and his people in the land of Helam. The Lamanites brought 19–20 ). them into bondage. (See Mosiah 22–24 .) The Lamanites attacked Noah’s people in the land of Nephi. -

Conversion of Alma the Younger

Conversion of Alma the Younger Mosiah 27 I was in the darkest abyss; but now I behold the marvelous light of God. Mosiah 27:29 he first Alma mentioned in the Book of Mormon Before the angel left, he told Alma to remember was a priest of wicked King Noah who later the power of God and to quit trying to destroy the Tbecame a prophet and leader of the Church in Church (see Mosiah 27:16). Zarahemla after hearing the words of Abinadi. Many Alma the Younger and the four sons of Mosiah fell people believed his words and were baptized. But the to the earth. They knew that the angel was sent four sons of King Mosiah and the son of the prophet from God and that the power of God had caused the Alma, who was also called Alma, were unbelievers; ground to shake and tremble. Alma’s astonishment they persecuted those who believed in Christ and was so great that he could not speak, and he was so tried to destroy the Church through false teachings. weak that he could not move even his hands. The Many Church members were deceived by these sons of Mosiah carried him to his father. (See Mosiah teachings and led to sin because of the wickedness of 27:18–19.) Alma the Younger. (See Mosiah 27:1–10.) When Alma the Elder saw his son, he rejoiced As Alma and the sons of Mosiah continued to rebel because he knew what the Lord had done for him. against God, an angel of the Lord appeared to them, Alma and the other Church leaders fasted and speaking to them with a voice as loud as thunder, prayed for Alma the Younger. -

May 18 – 24 Mosiah 25 – 28 “They Were Called the People of God”

Come, Follow Me: May 18 – 24 Mosiah 25 – 28 “They Were Called the People of God” We now have a coming together of all the Israelites in the New World, except for the rebellious Lamanites. The Mulekites of Zarahemla had been discovered by Mosiah (the first) and desired that he should rule over them. Zeniff had departed back to the Land of Nephi and his descendants had been oppressed by the Lamanites. God had delivered them, and they had arrived in Zarahemla. Alma (the Elder) had been a priest of the wicked King Noah (Zeniff’s son) who had been converted by the words of Abinadi. He had fled to the waters of Mormon and baptized about 400 people there. They had fled King Noah and established a city, which was overrun by Lamanites. After being persecuted, they were also delivered by God and had arrived in Zarahemla. What were God’s purposes in gathering these Israelites Figure 1Mosiah II by James Fullmer via (descendants of Judah—the Mulekites—and Joseph—the bookofmormonbattles.com Nephites) in one place? The people of Alma and Limhi in Zarahemla (Mosiah 25): Mosiah (the second, the son of King Benjamin) called all the people together in a great conference in two bodies. The Mulekites outnumbered the Nephites. Why did the Mulekites desire to be taught the language of the Nephites and have them rule? When they had been gathered (verse 5) he had the records of Zeniff’s people read to those who had gathered. All the people had wondered what had become of Zeniff. -

A Third Jaredite Record: the Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 11 Number 1 Article 10 7-31-2002 A Third Jaredite Record: The Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates Valentin Arts Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Arts, Valentin (2002) "A Third Jaredite Record: The Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 11 : No. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol11/iss1/10 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title A Third Jaredite Record: The Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates Author(s) Valentin Arts Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 11/1 (2002): 50–59, 110–11. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract In the Book of Mormon, two records (a large engraved stone and twenty-four gold plates) contain the story of an ancient civilization known as the Jaredites. There appears to be evidence of an unpublished third record that provides more information on this people and on the history of the world. When the brother of Jared received a vision of Jesus Christ, he was taught many things but was instructed not to share them with the world until the time of his death. The author proposes that the brother of Jared did, in fact, write those things down shortly before his death and then buried them, along with the interpreting stones, to be revealed to the world according to the timing of the Lord. -

EVIDENCE of the NEHOR RELIGION in MESOAMERICA

EVIDENCE of the NEHOR RELIGION in MESOAMERICA Jerry D. Grover Jr., PE, PG Evidence of the Nehor Religion in Mesoamerica Evidence of the Nehor Religion in Mesoamerica by Jerry D. Grover, Jr. PE, PG Jerry D. Grover, Jr., is a licensed Professional Structural and Civil Engineer and a licensed Professional Geologist. He has an undergraduate degree in Geological Engineering from BYU and a Master’s Degree in Civil Engineering from the University of Utah. He speaks Italian and Chinese and has worked with his wife as a freelance translator over the past 25 years. He has provided geotechnical and civil engineering design for many private and public works projects. He took a 12-year hiatus from the sciences and served as a Utah County Commissioner from 1995 to 2007. He is currently employed as the site engineer for the remediation and redevelopment of the 1750-acre Geneva Steel site in Vineyard, Utah. He has published numerous scientific and linguistic books centering on the Book of Mormon, all of which are available for free in electronic format at www.bmslr.org. Acknowledgments: This book is dedicated to my gregarious daughter, Shirley Grover Calderon, and her wonderful husband Marvin Calderon and his family who are of Mayan descent. Thanks are due to Sandra Thorne for her excellent editing, and to Don Bradley and Dr. Allen Christenson for their thorough reviews and comments. Peer Review: This book has undergone third-party blind review and third-party open review without distinction as to religious affiliation. As with all of my works, it will be available for free in electronic format on the open web, so hopefully there will be ongoing peer review in the form of book reviews, etc. -

Why Did the Lamanites Break Their Treaty with King Limhi?

KnoWhy #98 May 12, 2016 Lamanite Daughters by Minerva Teichert Why did the Lamanites Break Their Treaty with King Limhi? “And are not they the ones who have stolen the daughters of the Lamanites?” Mosiah 20:18 The Know After Abinadi’s martyrdom1 and Alma the El- in the capital city of Nephi (Mosiah 20:6–11),2 der’s flight into the wilderness, the Lamanites whom the Lamanites assumed were connected were seen again in the borders of the land of with the taking of their daughters. Commenting Nephi (Mosiah 19:6). While king Noah fled with on this passage, S. Kent Brown speculated, “In many of his men (19:11), some stayed with their the end, the [Lamanite] king’s decision to destroy women and entered into a treaty with the La- the Nephite colony must have rested on a com- manites, agreeing to pay “half of all they pos- bination of considerations, one of which was his sessed” (19:15) in order to remain on their lands. feeling of anger.”3 Meanwhile, king Noah was put to a fiery death by some of his men who now wanted to return Readers can understand this anger on the part to their wives back in the land of Nephi (19:20). of the Lamanites. Not only were their daugh- Noah’s priests, however, fled (19:21), and soon ters the victims of a sexual crime, but con- thereafter they abducted 24 Lamanite maidens quered subjects appeared to be rising in defi- “and carried them into the wilderness” (Mosiah ance. -

Why Did the Nephites Practice Baptism? Behold, Here Are the Waters of Mormon

KnoWhy #320 May 31, 2017 Aguas de Mormon by Jorge Cocco Why Did the Nephites Practice Baptism? Behold, here are the waters of Mormon ... and now, as ye are desirous to come into the fold of God, and to be called his people, and are willing to bear one another’s burdens, that they may be light …. Now I say unto you, if this be the desire of your hearts, what have you against being baptized in the name of the Lord, as a witness before him that ye have entered into a covenant with him, that ye will serve him and keep his commandments, that he may pour out his Spirit more abundantly upon you?” Mosiah 18:8–10 Context & Content jjkl In Mosiah 18, Alma the Elder, who had been one teous people of King Limhi wanted to be baptized, of King Noah’s priests until being converted by they understood that baptism was meant to be “a Abinadi’s preaching, led a large group of people witness and a testimony that they were willing to to be baptized in the “waters of Mormon.” Mosiah serve God with all their hearts” (Mosiah 21:35; cf. 18:1 says that Alma first “repented of his sins and 3 Nephi 7:25). iniquities,” and then “began to teach the words of Abinadi.” Those who believed his teachings went A covenant is a promise between two parties, each to a place called “Mormon,”1 where there was “a agreeing to do something for the other, if the other fountain of pure water” (vv. -

Mosiah Like the Lamanites, Who Know Nothing King Benjamin Teaches Sons About God's Commandments and See Mosiah, Chapter 1 Mysteries

!139 A Plain English Reference to have faltered in unbelief. We would be The Book of Mosiah like the Lamanites, who know nothing King Benjamin teaches sons about God's commandments and See Mosiah, Chapter 1 mysteries. They don't believe these things because they are misguided by This peace among all the people in the their forefathers' false traditions. land of Zarahemla lasted for the rest of Remember this, for these records are King Benjamin's days. He had three true. sons, Mosiah, Helorum and Helaman, and taught them the writing language of And these plates Nephi made, which their forefathers — modified Egyptian. contain our forefathers' words from the time they left Jerusalem until now, are He did this so they would become men also true. Remember to search them of understanding, knowing the diligently so you may profit from them. prophecies the Lord had given their forefathers (engraved on Nephi's I want you to obey God’s commands plates). so you will prosper in the land, according to the promises He made to Benjamin also taught his sons our forefathers." concerning the records engraved on the brass plates, saying, King Benjamin taught many more things to his sons not written here. "My sons, I want you to remember, if it were not for these plates containing As he grew old and realized he would records and commandments, we would soon die, he felt it necessary to confer now be in ignorance, not knowing the the kingdom upon one of his sons. And mysteries of God. It would have been so he called for Mosiah, named after impossible for our forefather Lehi to his grandfather, and said to him, have remembered all these things, and "My son, I want you to make a to have taught them to his children proclamation throughout all the land of without these plates. -

Charting the Book of Mormon, © 1999 Welch, Welch, FARMS Life Spans of Lehi’S Lineage

Section 3 Chronology of the Book of Mormon Charts 26–40 Chronology Chart 26 Life Spans of Lehi’s Lineage Key Scripture 1 Nephi–Omni Explanation This chart shows the lineage of Lehi and approximate life spans of him and his descendants, from Nephi to Amaleki, who were re- sponsible for keeping the historical and doctrinal records of their people. Each bar on the chart represents an individual record keeper’s life. Although the Book of Mormon does not give the date of Nephi’s death, it makes good sense to assume that he was approximately seventy-five years old when he died. Source John W. Welch, “Longevity of Book of Mormon People and the ‘Age of Man,’” Journal of Collegium Aesculapium 3 (1985): 34–45. Charting the Book of Mormon, © 1999 Welch, Welch, FARMS Life Spans of Lehi’s Lineage Life span Lehi Life span with unknown date of death Nephi Jacob Enos Jarom Omni Amaron Chemish Abinadom Amaleki 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 YEARS B.C. Charting the Book of Mormon, © 1999 Welch, Welch, FARMS Chart 26 Chronology Chart 27 Life Spans of Mosiah’s Lineage Key Scripture Omni–Alma 27 Explanation Mosiah and his lineage did much to bring people to Jesus Christ. After being instructed by the Lord to lead the people of Nephi out of the land of Nephi, Mosiah preserved their lives and brought to the people of Zarahemla the brass plates and the Nephite records. He also taught the people of Zarahemla the gospel and the lan- guage of the Nephites, and he was made king over both Nephites and Mulekites. -

TEACHINGS of the BOOK of MORMON HUGH NIBLEY Semester 2, Lecture 32 Mosiah 8–10 Ammon and Limhi the Record of Zeniff

TEACHINGS OF THE BOOK OF MORMON HUGH NIBLEY Semester 2, Lecture 32 Mosiah 8–10 Ammon and Limhi The Record of Zeniff We are on chapter 8 of Mosiah, and it is absolutely staggering what’s in here. I’ve been missing everything all these years. We can’t stop for everything, but nevertheless it’s jammed in here. Remember that Ammon has come to King Limhi and has been invited to speak to the king. He’s in the palace now, and it follows strictly the proper palace procedure as you get it in all the epics, etc. Limhi makes an end of speaking. He tells his story, and then he invites the guest to speak and tell his story. This is a thing that is common in epics, of course. When Odysseus comes to the Phaeacians, the king of the Phaeacians is Alcinous, and he gives a long speech that runs through two books explaining how they happened to get there. Then he says to the guest as he is about to leave at the beginning of the ninth book, “Now tell us your story.” So Odysseus starts out, “I am Odysseus, the son of Laertes, noted throughout the world for my sufferings [everybody is watching my sufferings] and my fame goes to heaven. I live in Ithica [and he describes what a beautiful land it is]. It’s rough but it’s a good land, a nourisher of people rather than nothing.” The way it skips along is a marvelous thing, and then two lines later he tells how he lived for ten years with the nymph Calypso.