Law and War in the Book of Mormon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events Earl M. Wunderli DURING THE PAST FEW DECADES, a number of LDS scholars have developed various "limited geography" models of where the events of the Book of Mormon occurred. These models contrast with the traditional western hemisphere model, which is still the most familiar to Book of Mormon readers. Of the various models, the only one to have gained a following is that of John Sorenson, now emeritus professor of anthropology at Brigham Young University. His model puts all the events of the Book of Mormon essentially into southern Mexico and southern Guatemala with the Isthmus of Tehuantepec as the "narrow neck" described in the LDS scripture.1 Under this model, the Jaredites and Nephites/Lamanites were relatively small colonies living concurrently with other peoples in- habiting the rest of the hemisphere. Scholars have challenged Sorenson's model based on archaeological and other external evidence, but lay people like me are caught in the crossfire between the experts.2 We, however, can examine Sorenson's model based on what the Book of Mormon itself says. One advantage of 1. John L. Sorenson, "Digging into the Book of Mormon," Ensign, September 1984, 26- 37; October 1984, 12-23, reprinted by the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS); An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: De- seret Book Company, and Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1985); The Geography of Book of Mormon Events: A Source Book (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1990); "The Book of Mormon as a Mesoameri- can Record," in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited, ed. -

Juvenile Instructor 16 (1 April 1881): 82

G. G.001 G. “Old Bottles and Elephants.” Juvenile Instructor 16 (1 April 1881): 82. Discusses earthenware manufacture in antiquity. Points out that some bottles and pottery vessels dug up on the American continent resemble elephants. Also mentions that the discovery of elephant bones in the United States tend to prove the truth of the Jaredite record. [A.C.W.] G.002 G., L. A. “Prehistoric People.” SH 51 (16 November 1904): 106-7. Quoting a clipping from the Denver Post written by Doctor Baum who had conducted expeditions in the southwestern United States, the author wonders why the archaeologists do not read the Book of Mormon to nd answers to their questions about ancient inhabitants of America. [J.W.M.] G.003 Gabbott, Mabel Jones. “Abinadi.” Children’s Friend 61 (September 1962): 44-45. A children’s story of Abinadi preaching to King Noah. [M.D.P.] G.004 Gabbott, Mabel Jones. “Alma.” Children’s Friend 61 (October 1962): 12-13. A children’s story of how Alma believed Abinadi and then organized the Church of Christ after preaching in secret to the people. [M.D.P.] G.005 Gabbott, Mabel Jones. “Alma, the Younger.” Children’s Friend 61 (December 1962): 18-19. A children’s story of the angel that appeared to Alma the Younger and the four sons of Mosiah and how they were converted by this experience. [M.D.P.] G.006 Gabbott, Mabel Jones. “Ammon.” Children’s Friend 62 (February 1963): 18-19. A children’s story of Ammon teaching among the Lamanites. [M.D.P.] G.007 Gabbott, Mabel Jones. -

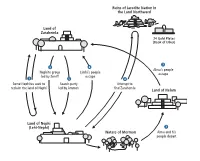

Land of Zarahemla Land of Nephi (Lehi-Nephi) Waters of Mormon

APPENDIX Overview of Journeys in Mosiah 7–24 1 Some Nephites seek to reclaim the land of Nephi. 4 Attempt to fi nd Zarahemla: Limhi sends a group to fi nd They fi ght amongst themselves, and the survivors return to Zarahemla and get help. The group discovers the ruins of Zarahemla. Zeniff is a part of this group. (See Omni 1:27–28 ; a destroyed nation and 24 gold plates. (See Mosiah 8:7–9 ; Mosiah 9:1–2 .) 21:25–27 .) 2 Nephite group led by Zeniff settles among the Lamanites 5 Search party led by Ammon journeys from Zarahemla to in the land of Nephi (see Omni 1:29–30 ; Mosiah 9:3–5 ). fi nd the descendants of those who had gone to the land of Nephi (see Mosiah 7:1–6 ; 21:22–24 ). After Zeniff died, his son Noah reigned in wickedness. Abinadi warned the people to repent. Alma obeyed Abinadi’s message 6 Limhi’s people escape from bondage and are led by Ammon and taught it to others near the Waters of Mormon. (See back to Zarahemla (see Mosiah 22:10–13 ). Mosiah 11–18 .) The Lamanites sent an army after Limhi and his people. After 3 Alma and his people depart from King Noah and travel becoming lost in the wilderness, the army discovered Alma to the land of Helam (see Mosiah 18:4–5, 32–35 ; 23:1–5, and his people in the land of Helam. The Lamanites brought 19–20 ). them into bondage. (See Mosiah 22–24 .) The Lamanites attacked Noah’s people in the land of Nephi. -

Conversion of Alma the Younger

Conversion of Alma the Younger Mosiah 27 I was in the darkest abyss; but now I behold the marvelous light of God. Mosiah 27:29 he first Alma mentioned in the Book of Mormon Before the angel left, he told Alma to remember was a priest of wicked King Noah who later the power of God and to quit trying to destroy the Tbecame a prophet and leader of the Church in Church (see Mosiah 27:16). Zarahemla after hearing the words of Abinadi. Many Alma the Younger and the four sons of Mosiah fell people believed his words and were baptized. But the to the earth. They knew that the angel was sent four sons of King Mosiah and the son of the prophet from God and that the power of God had caused the Alma, who was also called Alma, were unbelievers; ground to shake and tremble. Alma’s astonishment they persecuted those who believed in Christ and was so great that he could not speak, and he was so tried to destroy the Church through false teachings. weak that he could not move even his hands. The Many Church members were deceived by these sons of Mosiah carried him to his father. (See Mosiah teachings and led to sin because of the wickedness of 27:18–19.) Alma the Younger. (See Mosiah 27:1–10.) When Alma the Elder saw his son, he rejoiced As Alma and the sons of Mosiah continued to rebel because he knew what the Lord had done for him. against God, an angel of the Lord appeared to them, Alma and the other Church leaders fasted and speaking to them with a voice as loud as thunder, prayed for Alma the Younger. -

May 18 – 24 Mosiah 25 – 28 “They Were Called the People of God”

Come, Follow Me: May 18 – 24 Mosiah 25 – 28 “They Were Called the People of God” We now have a coming together of all the Israelites in the New World, except for the rebellious Lamanites. The Mulekites of Zarahemla had been discovered by Mosiah (the first) and desired that he should rule over them. Zeniff had departed back to the Land of Nephi and his descendants had been oppressed by the Lamanites. God had delivered them, and they had arrived in Zarahemla. Alma (the Elder) had been a priest of the wicked King Noah (Zeniff’s son) who had been converted by the words of Abinadi. He had fled to the waters of Mormon and baptized about 400 people there. They had fled King Noah and established a city, which was overrun by Lamanites. After being persecuted, they were also delivered by God and had arrived in Zarahemla. What were God’s purposes in gathering these Israelites Figure 1Mosiah II by James Fullmer via (descendants of Judah—the Mulekites—and Joseph—the bookofmormonbattles.com Nephites) in one place? The people of Alma and Limhi in Zarahemla (Mosiah 25): Mosiah (the second, the son of King Benjamin) called all the people together in a great conference in two bodies. The Mulekites outnumbered the Nephites. Why did the Mulekites desire to be taught the language of the Nephites and have them rule? When they had been gathered (verse 5) he had the records of Zeniff’s people read to those who had gathered. All the people had wondered what had become of Zeniff. -

A Third Jaredite Record: the Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 11 Number 1 Article 10 7-31-2002 A Third Jaredite Record: The Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates Valentin Arts Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Arts, Valentin (2002) "A Third Jaredite Record: The Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 11 : No. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol11/iss1/10 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title A Third Jaredite Record: The Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates Author(s) Valentin Arts Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 11/1 (2002): 50–59, 110–11. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract In the Book of Mormon, two records (a large engraved stone and twenty-four gold plates) contain the story of an ancient civilization known as the Jaredites. There appears to be evidence of an unpublished third record that provides more information on this people and on the history of the world. When the brother of Jared received a vision of Jesus Christ, he was taught many things but was instructed not to share them with the world until the time of his death. The author proposes that the brother of Jared did, in fact, write those things down shortly before his death and then buried them, along with the interpreting stones, to be revealed to the world according to the timing of the Lord. -

Why Did the Lamanites Break Their Treaty with King Limhi?

KnoWhy #98 May 12, 2016 Lamanite Daughters by Minerva Teichert Why did the Lamanites Break Their Treaty with King Limhi? “And are not they the ones who have stolen the daughters of the Lamanites?” Mosiah 20:18 The Know After Abinadi’s martyrdom1 and Alma the El- in the capital city of Nephi (Mosiah 20:6–11),2 der’s flight into the wilderness, the Lamanites whom the Lamanites assumed were connected were seen again in the borders of the land of with the taking of their daughters. Commenting Nephi (Mosiah 19:6). While king Noah fled with on this passage, S. Kent Brown speculated, “In many of his men (19:11), some stayed with their the end, the [Lamanite] king’s decision to destroy women and entered into a treaty with the La- the Nephite colony must have rested on a com- manites, agreeing to pay “half of all they pos- bination of considerations, one of which was his sessed” (19:15) in order to remain on their lands. feeling of anger.”3 Meanwhile, king Noah was put to a fiery death by some of his men who now wanted to return Readers can understand this anger on the part to their wives back in the land of Nephi (19:20). of the Lamanites. Not only were their daugh- Noah’s priests, however, fled (19:21), and soon ters the victims of a sexual crime, but con- thereafter they abducted 24 Lamanite maidens quered subjects appeared to be rising in defi- “and carried them into the wilderness” (Mosiah ance. -

Criminal Complaint

Case 1:21-mj-00526-RMM Document 1 Filed 07/14/21 Page 1 of 1 AO 91 (Rev. 11/11) Criminal Complaint UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the District of &ROXPELD United States of America ) v. ) ) ) ) 1$7+$1 :$<1( (175(.,1 ) DOB: ;;;;;; ) Defendant CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I, the complainant in this case, state that the following is true to the best of my knowledge and belief. On or about the date(s) of January 6, 2021 in the county of in the LQ WKH 'LVWULFW RI &ROXPELD , the defendant(s) violated: Code Section Offense Description 18 U.S.C. § 1752(a)(1) ²Knowingly Entering or Remaining in any Restricted Building or Grounds Without Lawful Authority 40 U.S.C. § 5104(e)(2) & L ' * ²Violent Entry and Disorderly Conduct on Capitol Grounds This criminal complaint is based on these facts: 6HH DWWDFKHG VWDWHPHQW RI IDFWV 9u Continued on the attached sheet. 7UHYRU &XOEHUW, Special Agent Printed name and title $WWHVWHG WR E\ WKH DSSOLFDQW LQ DFFRUGDQFH ZLWK WKH UHTXLUHPHQWV RI )HG 5 &ULP 3 E\ WHOHSKRQH 2021.07.14 Date: -XO\ 12:29:42 -04'00' Judge’s signature City and state: :DVKLQJWRQ '& 5RELQ 0 0HULZHDWKHU, U.S. Magistrate Judge Printed name and title Case 1:21-mj-00526-RMM Document STATEMENT OF FACTS Your affiant, is a Special Agent (SA) with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and has been so employed since March 2004. I am currently assigned to Phoenix Division, Flagstaff Resident Agency. My duties include investigating violations of the laws of the United States, specifically investigations related to domestic and foreign terrorism. -

Priesthood Concepts in the Book of Mormon

s u N S T O N E Unique perspectives on Church leadership and organi zation PRIESTHOOD CONCEPTS IN THE BOOK OF MORMON By Paul James Toscano THE BOOK OF MORMON IS PROBABLY THE EARLI- people." The phrasing and context of this verse suggests that est Mormon scriptural text containing concepts relating to boththe words "priest" and "teacher" were not used in our modern the structure and the nature of priesthood. This book, printed sense to designate offices within a priestly order or structure, between August 1829 and March 1830, is the first published such as deacon, priest, bishop, elder, high priest, or apostle. scripture of Mormonism but was preceded by seventeen other Nor were they used to designate ecclesiastical offices, such as then unpublished revelations, many of which eventually appearedcounselor, stake president, quorum president, or Church presi- in the 1833 Book of Commandments and later in the 1835 dent. They appear to refer only to religious functions. Possibly, edition of the Doctrine and Covenants. Prior to their publica- the teacher was one who expounded and admonished the tion, most or all of these revelations existed in handwritten formpeople; the priest ~vas possibly one who mediated between and undoubtedly had limited circulation. God and his people, perhaps to administer the ordinances of While the content of many of these revelations (now sec-the gospel and the rituals of the law of Moses, for we are told tions 2-18) indicate that priesthood concepts were being dis- by Nephi that "notwithstanding we believe in Christ, we keep cussed in the early Church, from 1830 until 1833 the Book the law of Moses" (2 Nephi 25: 24). -

Doctrine and Covenants Student Manual Religion 324 and 325

Doctrine and Covenants Student Manual Religion 324 and 325 Prepared by the Church Educational System Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah Send comments and corrections, including typographic errors, to CES Editing, 50 E. North Temple Street, Floor 8, Salt Lake City, UT 84150-2722 USA. E-mail: <[email protected]> Second edition © 1981, 2001 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 4/02 Table of Contents Preface . vii Section 21 Maps . viii “His Word Ye Shall Receive, As If from Mine Own Mouth” . 43 Introduction The Doctrine and Covenants: Section 22 The Voice of the Lord to All Men . 1 Baptism: A New and Everlasting Covenant . 46 Section 1 The Lord’s Preface: “The Voice Section 23 of Warning”. 3 “Strengthen the Church Continually”. 47 Section 2 Section 24 “The Promises Made to the Fathers” . 6 “Declare My Gospel As with the Voice of a Trump” . 48 Section 3 “The Works and the Designs . of Section 25 God Cannot Be Frustrated” . 9 “An Elect Lady” . 50 Section 4 Section 26 “O Ye That Embark in the Service The Law of Common Consent . 54 of God” . 11 Section 27 Section 5 “When Ye Partake of the Sacrament” . 55 The Testimony of Three Witnesses . 12 Section 28 Section 6 “Thou Shalt Not Command Him Who The Arrival of Oliver Cowdery . 14 Is at Thy Head”. 57 Section 7 Section 29 John the Revelator . 17 Prepare against the Day of Tribulation . 59 Section 8 Section 30 The Spirit of Revelation . -

Why Did the Nephites Practice Baptism? Behold, Here Are the Waters of Mormon

KnoWhy #320 May 31, 2017 Aguas de Mormon by Jorge Cocco Why Did the Nephites Practice Baptism? Behold, here are the waters of Mormon ... and now, as ye are desirous to come into the fold of God, and to be called his people, and are willing to bear one another’s burdens, that they may be light …. Now I say unto you, if this be the desire of your hearts, what have you against being baptized in the name of the Lord, as a witness before him that ye have entered into a covenant with him, that ye will serve him and keep his commandments, that he may pour out his Spirit more abundantly upon you?” Mosiah 18:8–10 Context & Content jjkl In Mosiah 18, Alma the Elder, who had been one teous people of King Limhi wanted to be baptized, of King Noah’s priests until being converted by they understood that baptism was meant to be “a Abinadi’s preaching, led a large group of people witness and a testimony that they were willing to to be baptized in the “waters of Mormon.” Mosiah serve God with all their hearts” (Mosiah 21:35; cf. 18:1 says that Alma first “repented of his sins and 3 Nephi 7:25). iniquities,” and then “began to teach the words of Abinadi.” Those who believed his teachings went A covenant is a promise between two parties, each to a place called “Mormon,”1 where there was “a agreeing to do something for the other, if the other fountain of pure water” (vv. -

Charting the Book of Mormon, © 1999 Welch, Welch, FARMS Book of Mormon Plates and Records

Section 2 The Structure of the Book of Mormon Charts 13–25 Structure Chart 13 Book of Mormon Plates and Records Key Scripture Words of Mormon 1:3–11 Explanation Many ancient documents such as King Benjamin’s speech or the plates of brass were quoted or abridged by the ancient authors who compiled the books found on the small and large plates of Nephi. The abridgments, quotations, and original writings of those Book of Mormon historians are displayed on the left-hand and middle columns of this chart and are then shown in relation to the new set of plates produced by Mormon and Moroni that was delivered to Joseph Smith by the angel Moroni. Joseph dictated the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon from the plates of Mormon. Copying that original manuscript, parts of which survive today, Oliver Cowdery prepared a printer’s manuscript (owned by the RLDS Church). The first edition of the Book of Mormon was typeset from that printer’s manuscript. Source Grant R. Hardy and Robert E. Parsons, “Book of Mormon Plates and Records,” in Daniel H. Ludlow, ed., Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 5 vols. (1992), 1:196. Charting the Book of Mormon, © 1999 Welch, Welch, FARMS Book of Mormon Plates and Records Quotation Abridgment Record of Lehi Small Plates of Nephi Plates 1 & 2 Nephi, Jacob, of Brass Enos, Jarom, Omni Benjamin’s Words of Speech Mormon Book of Lehi Record (lost 116 pages) of Zeniff Large Plates of Nephi Records Lehi, Mosiah, Alma, of Alma Helaman, 3 & 4 Nephi Plates of Records of Sons Mormon Mormon of Mosiah Sealed Plates Epistles of (not translated) Helaman, Pahoran, Moroni Ether Records of Nephi3 Records of Moroni the Jaredites Documents Title Page from Mormon The Book Printer’s Original of Mormon Manuscript Manuscript 1830 1829–30 1829 Charting the Book of Mormon, © 1999 Welch, Welch, FARMS Chart 13 Structure Chart 14 Contents of the Plates of Brass Key Scripture 1 Nephi 5:11–14 Explanation The plates of brass contained a copy of the Law (five books of Moses), a history of the Jews, Lehi’s genealogy, and the writings of many prophets.