Anecdotally Queer: the Then and There of My Prairie Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(1933(1933 -- 2021)2021) Bowie

YOUR FREE GUIDE TO BOOKS & AUTHORS “We have lost a giant.” BC Premier John Horgan BOOKWORLD VOL. 35 • NO. 2 • Summer 2021 TOMTOM BERGERBERGER PHOTO (1933(1933 -- 2021)2021) BOWIE HeHe listenedlistened toto thethe NorthNorth GEOFF and he was vital in validating #40010086 and he was vital in validating Indigenous land claims. AGREEMENT Indigenous land claims. MAIL PHOTO page 7 BOWIE PUBLICATION GEOFF CEDAR BOWERS HARD LIQOUR HOWARD WHITE Raised in a commune, a Artisanal distilleries Fifty humorous sketches woman takes on city life. 23 on Vancouver Island. 14 of West Coast life. 5 t t PRINTED??????/TARA / BEV o rc om abook.c Let’s celebrate kids and teens (and puppies) being themselves! 9781459831377 PB $24.95 9781459826380 HC $19.95 9781459824843 HC $19.95 Stories, essays, art and poetry “A compassionate look at dysmorphia… “[A] sheer delight. Highly—and created by trans youth aged 11 to 18. and how family support can encourage proudly—recommended.” Our lives. Our voices. self-acceptance and self-love.” —Kirkus Reviews, starred review —School Library Journal, starred review “Successfully testifies to the warmth and power of queer community.” —Publishers Weekly, starred review Look for these books and more at your favourite bookstore. Orca Book Publishers is proud to now distribute… Flamingo Rampant Flamingo Rampant produces feminist, racially-diverse children’s books that celebrate LGBT2Q kids, families and communities, in an eff ort to bring visibility and positivity to the reading landscape of children everywhere. We make books kids love that love them right back, bedtime stories for beautiful dreams, and books that make kids of all kinds say with pride: that kid’s just like me! 9780987976352 • $15.95 • PB 9780987976383 • $15.95 • PB 9780987976345 • $15.95 • PB 2 BC BOOKWORLD • SUMMER 2021 BC TOP PEOPLE SELLERS Richard Wagamese A Perfect Likeness: Two Novellas . -

2016 Wordfest Authors – the List

2016 Wordfest authors – The List Meeting an actual person who wrote an Rencontrer LA personne qui a écrit un livre -en actual book -especially one that students particulier celui que les élèves ont lu et apprécié- have read and enjoyed- is a rare, captivating est une expérience relativement rare, captivante and transformative experience. Wordfest et précieuse. Wordfest et le Festival des mots Youth supplies authors from across Canada rassemblent des auteurs et illustrateurs du and around the world to present fun, inspiring Canada du monde entier pour favoriser ces in- and out-of-school events that promote a rencontres entre élèves et auteurs lors love of reading and a deeper appreciation of d’événements en théâtre et en école qui the written word. favorisent un amour de la lecture et une appréciation plus profonde de la littérature. Looking for a book of interest for your Vous cherchez un livre intéressant pour vos students? Look no further! The reading list élèves ? Ne cherchez plus! La liste de livres ci- below, organized by grade level, regroup all dessous, organisée par niveau scolaire, the artists available to visit your school1, from regroupe tous les artistes souhaitant visiter votre Kindergarten to Grade 12. école, de la maternelle à la 12e année. Contact Wordfest to discuss your needs and Contactez Wordfest pour discuter de vos the artist you’d like to meet; depending on besoins et de l'artiste que vous souhaitez their availability, we will definitely work with rencontrer; en fonction de leur disponibilité1, you to create an event that will inspire your nous travaillons avec vous pour créer un students. -

From “Telling Transgender Stories” to “Transgender People Telling Stories”: Transgender Literature and the Lambda Literary Awards, 1997-2017

FROM “TELLING TRANSGENDER STORIES” TO “TRANSGENDER PEOPLE TELLING STORIES”: TRANSGENDER LITERATURE AND THE LAMBDA LITERARY AWARDS, 1997-2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Andrew J. Young May 2018 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Dustin Kidd, Advisory Chair, Sociology Dr. Judith A. Levine, Sociology Dr. Tom Waidzunas, Sociology Dr. Heath Fogg Davis, External Member, Political Science © Copyright 2018 by Andrew J. Yo u n g All Rights Res erved ii ABSTRACT Transgender lives and identities have gained considerable popular notoriety in the past decades. As part of this wider visibility, dominant narratives regarding the “transgender experience” have surfaced in both the community itself and the wider public. Perhaps the most prominent of these narratives define transgender people as those living in the “wrong body” for their true gender identity. While a popular and powerful story, the wrong body narrative has been criticized as limited, not representing the experience of all transgender people, and valorized as the only legitimate identifier of transgender status. The dominance of this narrative has been challenged through the proliferation of alternate narratives of transgender identity, largely through transgender people telling their own stories, which has the potential to complicate and expand the social understanding of what it means to be transgender for both trans- and cisgender communities. I focus on transgender literature as a point of entrance into the changing narratives of transgender identity and experience. This work addresses two main questions: What are the stories being told by trans lit? and What are the stories being told about trans literature? What follows is a series of separate, yet linked chapters exploring the contours of transgender literature, largely through the context of the Lambda Literary Awards over the past twenty years. -

Xtra Living the BEST of TORONTO’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS GAY & LESBIAN TORONTO More at Dailyxtra.Com Facebook.Com/Dailyxtra @Dailyxtra

#769 APRIL 17–30, 2014 FREE INSIDE! 36,000 AUDITED CIRCULATION Xtra Living THE BEST OF TORONTO’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS GAY & LESBIAN TORONTO More at at More dailyxtra.com dailyxtra.com facebook.com/dailyxtra facebook.com/dailyxtra @dailyxtra Raging homosHas the gay lobby E8 become the bully? 2 APRIL 17–30, 2014 XTRA! TORONTO’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS Ŕ TORONTO’S INSIDE THIS ISSUE! GAY & LESBIAN NEWS Roundup #769 APRIL 17–30, 2014 The Case Against 8 screens at Hot Docs. THE BEST OF GAY & LESBIAN TORONTO A taste of Havana Handcrafted wood furniture Riverdale café culture East-end art institution Exploring Kensington Market XTRA Published by Pink Triangle Press PUBLISHER & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Brandon Matheson EDITORIAL ON SCREEN MANAGING EDITOR Danny Glenwright ARTS EDITOR Phil Villeneuve COPY EDITOR Lesley Fraser EVENT LISTINGS: [email protected] CONTRIBUTE OR INQUIRE about Xtra’s editorial content: [email protected], [email protected] Hot Docs heats up EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS ISSUE Drasko Bogdanovic, Kyle Burton, Scott Now in its 19th year, the festival has grown to be a Dagostino, Chris Dupuis, Ryan English, Ryan major international showcase for documentary fi lm, G Hinds, Ryan Kerr, Becca Lemire, Justin Ling, Michael Lyons, Anna Pournikova, Dylan C featuring 197 entries from 43 countries E18 Robertson, Rob Salerno, Alejandro Santiago, Sissydude, Jeremy Willard ART & PRODUCTION CREATIVE DIRECTOR Lucinda Wallace GRAPHIC DESIGNERS Darryl Mabey, Editorial Local news Bryce Stuart, Landon Whittaker New projects underway ADVERTISING Spring Event. New blood at the BIA ADVERTISING & SALES DIRECTOR Ken Hickling By Danny Glenwright E4 in the Village E12 NATIONAL SALES MANAGER Jeff rey Hoff man th SALES ADMINISTRATION MANAGER Lexi Chuba Seasonal Credits End April 30 Feedback E4 History Boys SALES TEAM LEAD Lorilynn Barker One of history’s fi rst RETAIL ACCOUNTS MANAGERS Exceptional lease and fi nance rates available. -

Gaycalgary Magazine

SEPTEMBER 2013 ® ISSUE 119 • FREE The Voice of Alberta’s LGBT Community AJ McLean Boys will be Boys INTERVIEW WITH JOSEPH Rae Spoon GORDON-LEVITT Trans Musician at Folk Fest PLUS: Tyler Saint Matthew Rush Christopher Daniels Calgary Pride 2013 Coverage Scan to Read on Indigo Girls ...and more! Mobile Devices http://gettag.mobi Now Touring Canada Business Directory Community Map Events Calendar Tourist Information STARTING ON PAGE 55 Calgary • Alberta • Canada www.gaycalgary.com 2 GayCalgary Magazine #119, September 2013 www.gaycalgary.com www.gaycalgary.com GayCalgary Magazine #119, September 2013 3 4 GayCalgary Magazine #119, September 2013 www.gaycalgary.com Table of Contents SEPTEMBER 2013 ® Publisher: Steve Polyak 7 Surviving August Editor: Rob Diaz-Marino Publisher’s Column Sales: Steve Polyak Design & Layout: Rob Diaz-Marino, AraSteve Shimoon Polyak 10 No Redress for Past Discrimination Writers and Contributors ChrisMercedes Azzopardi, Allen, ChrisDave Azzopardi, Brousseau, Dallas Jason Barnes, Clevett, 12 Inside Out DaveAndrew Brousseau, Collins, RobSam Diaz-Marino,Casselman, Jason Janine Clevett, Eva Celeb superfan Ross Mathews on his own talk show, road to success AndrewTrotta, Collins,Marisa Hudson,Emily Collins, Evan Rob Kayne, Diaz-Marino, Stephen JanineLock, EvaLisa Trotta, Lunney, Jack Steve Fertig, Polyak, Glen RomeoHanson, San Joan and being a ‘full tilt’ gay Hilty,Vicente, Evan Krista Kayne, Sylvester, Stephen Nick Lock, Winnick Neil McMullen, and the AllanLGBT Neuwirth, Community Steve of Calgary,Polyak, Carey Edmonton, -

RAE SPOON EPK the Mark of a Gifted Songwriter Is the Ability to Create the Most Emotion with the Rae Spoon Is One of the Most Fewest Notes

RAE SPOON EPK The mark of a gifted songwriter is the ability to create the most emotion with the Rae Spoon is one of the most fewest notes. Rae Spoon is a master of important musicians working restraint, conveying both hope and hurt at in Canada today once through simple melodies, a skill that led to their Polaris Music Prize nomination nowtoronto.com for 2013’s My Prairie Home. exclaim.ca Rae Spoon is an award-winning nonbinary musician and author. They have released nine solo LISTEN TO albums spanning folk, indie rock and electronic genres and have toured across Canada and 2018 internationally. Rae was the subject and composer of the score for the National Film Board– produced musical-documentary My Prairie Home, which premiered at Sundance Film Festival in 2014. Rae owns and runs an indie record label called Coax Records that has released over twenty albums by Canadian and international artists. They have been nominated for two Polaris Prizes, a Lambda Literary Award and a Western Canadian Music Award. Rae Spoon’s bodiesofwater comes out on the twentieth anniversary of the first show Spoon ever played, and ten years after the release of their break-out album superioryouareinferior. As a non-binary person, Rae is no stranger to having an identity that doesn’t fit societal and legal structures. Like bodies, water is regulated and increasingly commodified, despite being bodiesofwater fundamental to life. On this, Spoon’s ninth album, they explore their common ground and on Bandcamp connections with the ocean surrounding their Vancouver Island home. Rae’s first book, First Spring Grass Fire, was published by Arsenal Pulp Press in 2012. -

Arts Letter Vol. 44 No. 2 March/April 2021

PENTICTON ART GALLERY Arts Letter March / April 2021 Vol. 44 No. 2 OUR MISSION OUR VALUES The Penticton Art Gallery exists The following inform all initiatives and shape the mission and vision to exhibit, interpret, preserve, statements of the Gallery: and promote the visual, artistic, and cultural heritage of Indige- Community Responsibility: the Gallery interacts with the communi- nous Peoples and of Canada; ty by designing programs that inspire, challenge, educate, and enter- and to educate and engage the tain while recognizing excellence in the visual arts. public on local, regional, and global social issues through the Professional Responsibility: the Gallery employs curatorial exper- visual arts. tise to implement the setting of exhibitions, programs, and services in accordance with nationally recognized professional standards of oper- ation. OUR VISION Fiscal Responsibility: the Gallery conducts its operations and pro- We envision a gallery accessible grams within the scope of the financial and human resources availa- to everyone as a vibrant public ble. space in service of our commu- nity, to foster greater social en- gagement, critical thinking, and Territorial Acknowledgement: the Penticton Art Gallery acknowl- creativity. edges that the land on which we gather is the unceded territory of the Sylix (Okanagan) Peoples. VISIT US GALLERY STAFF BOARD OF DIRECTORS 199 Marina Way Paul Crawford Eric Hanston Penticton, British Columbia Director/Curator President V2A 1H5, Canada [email protected] Kristine Lee Shepherd This -

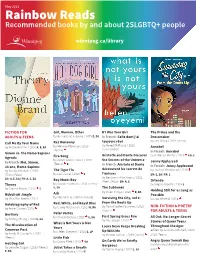

Rainbow Reads Recommended Books by and About 2SLGBTQ+ People

May 2021 Rainbow Reads Recommended books by and about 2SLGBTQ+ people winnipeg.ca/library FICTION FOR Girl, Woman, Other If I Was Your Girl The Prince and the ADULTS & TEENS by Bernardine Evaristo / 2019 E, EA In French: Celle dont j’ai Dressmaker Rez Runaway toujours rêvé by Jen Wang / 2018 (Teens) Call Me By Your Name by Meredith Russo / 2016 by André Aciman / 2007 A, E, EA by Melanie Florence / 2016 Annabel (Teens/Ados) (Teens) In French: Annabel Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Aristotle and Dante Discover by Kathleen Winter / 2010 EN: E Agenda Fire Song by Adam Garnet Jones / 2018 the Secrets of the Universe In French: Moi, Simon, Jonny Appleseed (Teens) E In French: Aristote et Dante 16 ans, Homo Sapiens In French: Jonny Appleseed by Becky Albertalli / 2015 The Tiger Flu découvrent les secrets de by Joshua Whitehead / 2018 (Teens/Ados) by Larissa Lai / 2018 E l’univers EN: E, EA | FR: E EN: A, E, EA | FR: A, E, EA by Benjamin Alire Sáenz / 2012 Boy Meets Boy (Teens/Ados) EN: A, E Orlando Theory by David Leviathan / 2003 (Teens) by Virgina Woolfe / 1928 E by Dionne Brand / 2018 E E, EA The Subtweet by Vivek Shraya / 2020 E, EA Holding Still for as Long as Rubyfruit Jungle Ash Possible by Rita Mae Brown / 1973 by Malinda Lo / 2009 (Teens) E Surviving the City, vol 2: by Zoe Whittall /2014 Red, White, and Royal Blue From the Roots Up Autobiography of Red by Tasha Spillett-Sumner / 2020 NON-FICTION & POETRY by Anne Carson / 1998 by Casey McQuiston / 2019 E, EA (Teens) FOR ADULTS & TEENS Bestiary Polar Vortex by Shani Mootoo / 2020 E, EA First Spring Grass Fire All Out: No-Longer-Secret by K-Ming Chang / 2020 E, EA by Rae Spoon / 2012 What is Not Yours is Not Stories of Queer Teens The Miseducation of Yours Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Throughout the Ages Cameron Post edited by Saundra Mitchell / 2020 by Helen Oyeyemi / 2016 E, LP Up With Me by Emily M. -

The Way We Look Matters: Witnessing. Trauma

THE WAY WE LOOK MATTERS: WITNESSING. TRAUMA. PERSPECTIVISM. by LOGAN ALEXANDER M.A., Brock University, 2012 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Interdisciplinary Studies) [Rhetoric/Philosophy/Performance Studies] THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2020 © Logan Alexander 2020 ii The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the thesis entitled: The Way We Look Maters: Witnessing. Trauma. Perspectivism_ submitted by Logan Alexander in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies Examining Committee: Dr. Steven Taubeneck, German, Philosophy and Interdisciplinary Studies Co-supervisor Dr. Janice Stewart, Institute of Gender, Race, Sexuality and Social Justice. Co-supervisor Additional Supervisory Committee Members: Dr. Carl Leggo, Language and Literacy Education Supervisory Committee Member iii Abstract This began as a film project. We took cameras and queer actors on a filmed/photographed walk in downtown Vancouver to demonstrate that people who look queer receive harsh micro-expressions when they are in public space. The photos were taken in public space and the actors consented to having their images used for this project. This is using the same public photography method used by Hayley Morris Caffiero (professor of photography) in her project Wait Watchers, where she photographed herself in public space and captured the micro-expressions of members of the public as a provocative statement about the type of treatment that fat people experience in public. I wanted to use this photographic method with queer people to demonstrate how queer people are looked at in public, and I wanted to interview the actors afterwards using a photo-elicited interview method where we would review the footage together during a debriefing interview. -

2016 – Calgary Alberta, Canada – Joint Meeting with IASPM Canada

IASPM-Canada and IASPM-US 2016 Conference Wanna Be Startin’ Something: Popular Music and Agency Congress 2016 University of Calgary Calgary, Alberta, Canada May 28 – 30, 2016 Friday, May 27 3:00–4:30 pm IASPM-US Executive Committee and Board of Directors Meeting Saturday, May 28 8:00-8:30 am registration 8:30-10:30 am Musicking in Place (Murray Fraser Hall Rm. 160) Katherine Meizel, moderator Rebekah Farrugia, Oakland University Kellie Hay, Oakland University Solutionaries in Action: The cultural production of three daring, Detroit Emcees Erin Bauer, Laramie County Community College San Antonio's Piñata Protest as Cultural Renegade: The (Self- Described) "Mojado-Punk" Convergence of Punk Rock and Texas- Mexican Accordion Music Natalie Oshukany, CUNY Graduate Center “Brighton Beach Has Long Been Odessan:” Musical and Cultural Negotiation Among “Third Wave” Soviet Jewish Immigrants in New York City Eugenia Siegel Conte, Wesleyan University Sounding Subcultural Hawai'i: Song and Soundscape in Alexander Payne's The Descendants Music and Labor (Professional Faculties Rm. 114) Chris McDonald, moderator Marco Accattatis, Rutgers University Work Hard, Play Hard: Normalizing Neoliberal Ideology in Popular Music Eric Hung, Rider University "Thank you, New York, No One Cooks": Social Justice and Undocumented Food Workers in the Hip Hop Musical Stuck Elevators 1 Martin Lussier, Université de Québec à Montréal “Assurer la relève”: movements of workers in Québec’s music industries Aesthetics and Ideologies (Professional Faculties Rm. 110) Esther Clinton, moderator Méi-Ra St. Laurent , Université Laval Vivek Venkatesh, Concordia University Québécois black metal: Developing intersections between musicology, social psychology and consumer culture in illuminating aesthetics and ideologies in a niche extreme metal music scene Victor Szabo, University of Virginia Ambient Music’s Techno-Aesthetics Nick Reeder, Matrix Recordings: The Role of Jamband Fans in Creating a Live Sound Aesthetic 10:45 am-12:15 pm Production, Consumption, Prosumption (Professional Faculties Rm. -

Program Title: My Prairie Home Program Subject(S) Gender

Program Title: My Prairie Home Program Subject(s) Gender Identity; Transgenderism; Folk Music Year Produced: 2013 Directed by Chelsea McMullan Produced by Lea Marin Distributed by National Film Board of Canada / Office National Du Film Du Canada Reviewed by Timothy Hackman, University of Maryland Running Time 77 minutes Color or B&W Color Awards Received Winner, Best Documentary, Vancouver Critics Circle Nominee, Best Feature Documentary, Canadian Screen Award Audience Level General Adult Review We open on a truck stop restaurant, somewhere in rural North America. The walls are painted pink and are adorned with a variety of kitschy décor, including a print of Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks, a gloomy painting of Jesus watching over a truck driver, another painting of a semi at sunset with light bulbs embedded in the picture. Waitresses dressed in pinkish purple scrubs circulate, filling coffee at booths upholstered in Route 66-themed fabric. The customers are mostly men, predominately overweight, a high proportion dressed in at least one article of denim clothing. At the counter, a person in a checked shirt, a guitar slung across one shoulder, sits on a stool, back to the camera. What appears to be a slim young man, with short hair and Buddy Holly glasses, turns around to face the camera, rises, takes the guitar, and begins to sing in a voice that is high, clear, beautiful, and distinctly feminine. The singer strolls through the diner, strumming and singing. Most of the customers ignore the performance, going on with their conversations and breakfasts; others cast a wary eye, perhaps worried that the singer will pass the hat for donations. -

LGBTQ+ Resource Centre Lakeshore Campus List of Books Name Of

LGBTQ+ Resource Centre Lakeshore Campus List of Books Name of Book and Author Ace & Proud: An Asexual Anthology Author: A.K. Andrews Against Equality - Queer Revolution Not Mere Inclusion Author: Ryan Conrad Am I Blue? Edited by: Marion Dane Bauer Another Day Author: David Levithan Beast Author: Brie Spangler Bow Grip Author: Ivan E. Coyote Boys Like Her Author: Kate Bornstein Butch is a Noun Author: S. Bear Bergman Calling Dr. Laura: A Graphic Memoir Author: Nicole Georges Close to spider man Author: Ivan E. Coyote Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability Author: Robert McRuer Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars: A Dangerous Trans Girl’s Confabulous Memoir Author: Kai Cheng Thom Fingersmith Author: Sarah Waters First Spring Grass Fire Author: Rae Spoon First Spring Grass Fire Author: Rae Spoon Funny Boy Author: Shyam Selvadurai Gender Failure Author: Rae Spoon & Ivan E. Coyote Girl Mans Up Author: M-E Girard Hold Me Closer Author: David Levithan If I Was Your Girl Author: Meredith Russo If You Could Be Mine Author: Sara Farizan Imagining Ourselves Author: Paula Goldman, Isabel Allende Loose End Author: Ivan E. Coyote Middlesex Author: Jeffrey Eugenides On Loving Women Author: Diane Obomsawin One in Every Crowd Author: Ivan E. Coyote One Mans Trash Author: Ivan E. Coyote Other Side of Paradise: A Memoir Author: Staceyann Chin Queer & Trans Artists of Colour Volume Two Author: Nia King Queering Social Work Education Author: Susan Hillock & Nick J Mule Rainbow Boys Author: Alex Sanchez Rainbow High Author: Alex Sanchez Rainbow Road Author: Alex Sanchez Skim Author: Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki Social Problems in a diverse society - 3rd Canadian Edition Author: Diane Kendal, Vivki L.