Bamako, Mali, 6-8 December 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meta-Analysis of Travel of the Poor in West and Southern African Cities Roger Behrens, Lourdes Diaz Olvera, Didier Plat, Pascal Pochet

Meta-analysis of travel of the poor in West and Southern african cities Roger Behrens, Lourdes Diaz Olvera, Didier Plat, Pascal Pochet To cite this version: Roger Behrens, Lourdes Diaz Olvera, Didier Plat, Pascal Pochet. Meta-analysis of travel of the poor in West and Southern african cities. WCTRS, ITU. 10th World Conference on Transport Research - WCTR’04, 4-8 juillet 2004, Istanbul, Turkey, 2004, Lyon, France. pp.19 P. halshs-00087977 HAL Id: halshs-00087977 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00087977 Submitted on 8 Oct 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 10th World Conference on Transport Research, Istanbul, 4-8 July 2004 META-ANALYSIS OF TRAVEL OF THE POOR IN WEST AND SOUTHERN AFRICAN CITIES Dr. Roger Behrens*, Dr. Lourdes Diaz-Olvera (corresponding author)**, Dr. Didier Plat**and Dr. Pascal Pochet** * Department of Civil Engineering, University of Cape Town, Private Bag, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa. Email: [email protected] ** Laboratoire d'Economie des Transports, ENTPE-Université Lumière Lyon 2-CNRS, rue Maurice Audin, 69518, Vaulx-en-Velin Cedex, France. Email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT There have been few attempts in the past to compare travel survey findings in francophone and anglophone African countries. -

Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Cities of Mali

Page 1 Policies for sustainable mobility and accessibility in cities of Mali Page 2 ¾ SSATP – Mali - Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Urban Areas – October 2019 Page 3 ¾ SSATP – Mali - Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Urban Areas – October 2019 Policies for sustainable mobility and accessibility in urban areas of Mali An international partnership supported by: Page 4 ¾ SSATP – Mali - Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Urban Areas – October 2019 The SSATP is an international partnership to facilitate policy development and related capacity building in the transport sector in Africa. Sound policies lead to safe, reliable, and cost-effective transport, freeing people to lift themselves out of poverty and helping countries to compete internationally. * * * * * * * The SSATP is a partnership of 42 African countries: Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe; 8 Regional Economic Communities (RECs); 2 African institutions: African Union Commission (AUC) and United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA); Financing partners for the Third Development Plan: European Commission (main donor), -

COUNTRY PROFILE: MALI January 2005 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Mali (République De Mali). Short Form: Mali. Term for Citi

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Mali, January 2005 COUNTRY PROFILE: MALI January 2005 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Mali (République de Mali). Short Form: Mali. Term for Citizen(s): Malian(s). Capital: Bamako. Major Cities: Bamako (more than 1 million inhabitants according to the 1998 census), Sikasso (113,813), Ségou (90,898), Mopti (79,840), Koutiala (74,153), Kayes (67,262), and Gao (54,903). Independence: September 22, 1960, from France. Public Holidays: In 2005 legal holidays in Mali include: January 1 (New Year’s Day); January 20 (Armed Forces Day); January 21* (Tabaski, Feast of the Sacrifice); March 26 (Democracy Day); March 28* (Easter Monday); April 21* (Mouloud, Birthday of the Prophet); May 1 (Labor Day); May 25 (Africa Day); September 22 (Independence Day); November 3–5* (Korité, end of Ramadan); December 25 (Christmas Day). Dates marked with an asterisk vary according to calculations based on the Islamic lunar or Christian Gregorian calendar. Flag: Mali’s flag consists of three equal vertical stripes of green, yellow, and red (viewed left to right, hoist side). Click to Enlarge Image HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: The area now constituting the nation of Mali was once part of three famed West African empires that controlled trans-Saharan trade in gold, salt, and other precious commodities. All of the empires arose in the area then known as the western Sudan, a vast region of savanna between the Sahara Desert to the north and the tropical rain forests along the Guinean coast to the south. All were characterized by strong leadership (matrilineal) and kin-based societies. -

Global Suicide Rates and Climatic Temperature

SocArXiv Preprint: May 25, 2020 Global Suicide Rates and Climatic Temperature Yusuke Arima1* [email protected] Hideki Kikumoto2 [email protected] ABSTRACT Global suicide rates vary by country1, yet the cause of this variability has not yet been explained satisfactorily2,3. In this study, we analyzed averaged suicide rates4 and annual mean temperature in the early 21st century for 183 countries worldwide, and our results suggest that suicide rates vary with climatic temperature. The lowest suicide rates were found for countries with annual mean temperatures of approximately 20 °C. The correlation suicide rate and temperature is much stronger at lower temperatures than at higher temperatures. In the countries with higher temperature, high suicide rates appear with its temperature over about 25 °C. We also investigated the variation in suicide rates with climate based on the Köppen–Geiger climate classification5, and found suicide rates to be low in countries in dry zones regardless of annual mean temperature. Moreover, there were distinct trends in the suicide rates in island countries. Considering these complicating factors, a clear relationship between suicide rates and temperature is evident, for both hot and cold climate zones, in our dataset. Finally, low suicide rates are typically found in countries with annual mean temperatures within the established human thermal comfort range. This suggests that climatic temperature may affect suicide rates globally by effecting either hot or cold thermal stress on the human body. KEYWORDS Suicide rate, Climatic temperature, Human thermal comfort, Köppen–Geiger climate classification Affiliation: 1 Department of Architecture, Polytechnic University of Japan, Tokyo, Japan. -

The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa Gillian Dunn Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/765 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa by Gillian Dunn A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Public Health in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Public Health, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 Gillian Dunn All Rights Reserved ii The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa by Gillian Dunn This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Public Health to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Public Health Deborah Balk, PhD Sponsor of Examining Committee Date Signature Denis Nash, PhD Executive Officer, Public Health Date Signature Examining Committee: Glen Johnson, PhD Grace Sembajwe, ScD Emmanuel d’Harcourt, MD THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Dissertation Abstract Title: The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa Author: Gillian Dunn Sponsor: Deborah Balk Objectives: This dissertation aims to contribute to our understanding of how climate variability and armed conflict impacts diarrheal disease and malnutrition among young children in West Africa. -

An Estimated Dynamic Model of African Agricultural Storage and Trade

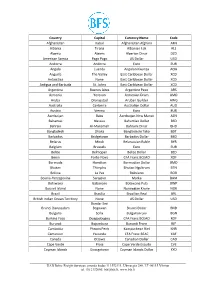

High Trade Costs and Their Consequences: An Estimated Dynamic Model of African Agricultural Storage and Trade Obie Porteous Online Appendix A1 Data: Market Selection Table A1, which begins on the next page, includes two lists of markets by country and town population (in thousands). Population data is from the most recent available national censuses as reported in various online databases (e.g. citypopulation.de) and should be taken as approximate as census years vary by country. The \ideal" list starts with the 178 towns with a population of at least 100,000 that are at least 200 kilometers apart1 (plain font). When two towns of over 100,000 population are closer than 200 kilometers the larger is chosen. An additional 85 towns (italics) on this list are either located at important transport hubs (road junctions or ports) or are additional major towns in countries with high initial population-to-market ratios. The \actual" list is my final network of 230 markets. This includes 218 of the 263 markets on my ideal list for which I was able to obtain price data (plain font) as well as an additional 12 markets with price data which are located close to 12 of the missing markets and which I therefore use as substitutes (italics). Table A2, which follows table A1, shows the population-to-market ratios by country for the two sets of markets. In the ideal list of markets, only Nigeria and Ethiopia | the two most populous countries | have population-to-market ratios above 4 million. In the final network, the three countries with more than two missing markets (Angola, Cameroon, and Uganda) are the only ones besides Nigeria and Ethiopia that are significantly above this threshold. -

Bamako Declaration on an African Common Position on the Illicit Proliferation, Circulation and Trafficking of Small Arms and Light Weapons

Bamako Declaration on an African Common Position on the Illicit Proliferation, Circulation and Trafficking of Small Arms and Light Weapons I. WE, THE MINISTERS of the Member States of the Organization of African Unity, met in Bamako, Mali, from 30 November to 1 December 2000, to develop an African Common Position on the Illicit Proliferation, Circulation and Trafficking of Small Arms and Light Weapons in preparation for the United Nations Conference on the Illicit Trade in Small Arms and Light Weapons in All Its Aspects, scheduled to take place in New York, from 9 to 20 July, 2001, in accordance with the relevant United Nations General Assembly Resolutions. Our meeting was held in pursuance of: i The Decision AHG/Dec. 137 (LXX), adopted by the 35th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government held in Algiers, Algeria, from 12 to 14 July 1999, which called for an African approach on the problems posed by the illicit proliferation, circulation and trafficking of small arms and light weapons, and for the convening of a Ministerial preparatory conference on this matter prior to the holding of the United Nations Conference; and the decisions adopted on this matter by the Council of Ministers, at its 68th Ordinary Session held in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, from 1 to 6 June 1998 (CM/Dec. 432 (LXVIII), the 71 " Ordinary Session held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, from 6 to 10 March 2000 (CM/Dec.501 (LXXI), and the 72nd Ordinary Session held in Lome, Togo, from 6 to 8 July 2000 (CM/Dec.527 (LXXII); II. -

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

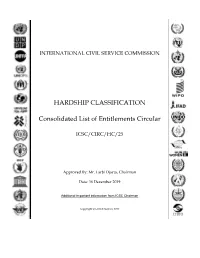

HARDSHIP CLASSIFICATION Consolidated List of Entitlements Circular

INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION HARDSHIP CLASSIFICATION Consolidated List of Entitlements Circular ICSC/CIRC/HC/25 Approved By: Mr. Larbi Djacta, Chairman Date: 16 December 2019 Additional important information from ICSC Chairman Copyright © United Nations 2017 United Nations International Civil Service Commission (HRPD) Consolidated list of entitlements - Effective 1 January 2020 Country/Area Name Duty Station Review Date Eff. Date Class Duty Station ID AFGHANISTAN Bamyan 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG002 AFGHANISTAN Faizabad 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG003 AFGHANISTAN Gardez 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG018 AFGHANISTAN Herat 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG007 AFGHANISTAN Jalalabad 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG008 AFGHANISTAN Kabul 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG001 AFGHANISTAN Kandahar 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG009 AFGHANISTAN Khowst 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 E AFG010 AFGHANISTAN Kunduz 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG020 AFGHANISTAN Maymana (Faryab) 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG017 AFGHANISTAN Mazar-I-Sharif 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG011 AFGHANISTAN Pul-i-Kumri 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG032 ALBANIA Tirana 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ALB001 ALGERIA Algiers 01/Jan/2018 01/Jan/2018 B ALG001 ALGERIA Tindouf 01/Jan/2018 01/Jan/2018 E ALG015 ALGERIA Tlemcen 01/Jul/2018 01/Jul/2018 C ALG037 ANGOLA Dundo 01/Jul/2018 01/Jul/2018 D ANG047 ANGOLA Luanda 01/Jul/2018 01/Jan/2018 B ANG001 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA St. Johns 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ANT010 ARGENTINA Buenos Aires 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ARG001 ARMENIA Yerevan 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 -

The Roots of Mali's Conflict

The roots of Mali’s conflict The roots Mali’s of The roots of Mali’s conflict Moving beyond the 2012 crisis CRU Report Grégory Chauzal Thibault van Damme The roots of Mali’s conflict Moving beyond the 2012 crisis Grégory Chauzal Thibault van Damme CRU report March 2015 The Sahel Programme is supported by March 2015 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holders. About the authors Grégory Chauzal is a senior research fellow at Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit. He specialises in Mali/Sahel issues and develops the Maghreb-Sahel Programme for the Institute. Thibault Van Damme works for Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit as a project assistant for the Maghreb-Sahel Programme. About CRU The Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ is a think tank and diplomatic academy on international affairs. The Conflict Research Unit (CRU) is a specialized team within the Institute, conducting applied, policy-oriented research and developing practical tools that assist national and multilateral governmental and non-governmental organizations in their engagement in fragile and conflict-affected situations. Clingendael Institute P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague The Netherlands Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl/ Table of Contents Acknowledgements 6 Executive summary 8 Introduction 10 1. The 2012 crisis: the fissures of a united insurrection 10 2. A coup in the south 12 3. -

REPUBLIC of MALI Bamako Sanitation Project Date

Project to Construct Two Faecal Sludge Treatment Plants in Bamako ESIA Summary Language: ENGLISH Original: FRENCH AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP COUNTRY : REPUBLIC OF MALI Bamako Sanitation Project Date : August 2016 Team Leader: El Hadji M’BAYE, Principal Water and Sanitation Engineer, OWAS.1 Team Members: B. CISSÉ, Senior Financial Analyst , OWAS.1 Team S. BARA, Senior Socio-Economist, OWAS.1 S. KITANE, Environmentalist, SNFO Sector Division Manager: Mrs. M. MOUMNI Sector Director: Mr. M. EL AZIZI, Director, OWAS/AWF Regional Director: Mr. BERNOUSSI A., Director, ORWA ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT SUMMARY Project to Construct Two Faecal Sludge Treatment Plants in Bamako ESIA Summary Project Name : Bamako Sanitation Project Country : MALI Project Number: P ML B00 004 Department : OWAS Division : OWAS.1 1. INTRODUCTION In efforts to update the Bamako Sanitation Master Plan (SDAB), a priority project to construct two faecal sludge disposal and treatment plants in Bamako has been identified. The project is designed to improve the living environment of the population by addressing the town’s acute sanitation problems. SOMAPEP SA initiated the project with the financial support of the African Development Bank. In accordance with Mali’s Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) procedure and AfDB operational safeguard on environmental and social impact assessment, the project has been classified under Environmental Category 1 (projects subject to environmental and social impact assessment). This document summarizes the environmental and social impact assessment report. It seeks to incorporate environmental concerns into the project planning. The assessment is conducted in accordance with the current procedure in the Republic of Mali and AfDB guidelines. -

The Challenges of Urbanization in West Africa

The Public Disclosure Authorized CHALLENGES of URBANIZATION in West Africa Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized COUNTRY FOCUS: GUINEA SPRING 2018 The CHALLENGES of URBANIZATION in West Africa ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................................................................................3 FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................................................................................4 SPECIAL TOPIC ...........................................................................................................................................................................7 Unlocking productivity and livability ...........................................................................................................................7 COUNTRY FOCUS: GUINEA ............................................................................................................................................42 COUNTRY ECONOMIC FOCUS .....................................................................................................................................59 CHAD ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 60 MALI ..............................................................................................................................................................................................