Aristocratic Landscape : the Spatial Ideology of the Medieval Aristocracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

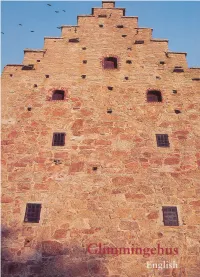

Digitalisering av redan tidigare utgivna vetenskapliga publikationer Dessa fotografier är offentliggjorda vilket innebär att vi använder oss av en undantagsregel i 23 och 49 a §§ lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk (URL). Undantaget innebär att offentliggjorda fotografier får återges digitalt i anslutning till texten i en vetenskaplig framställning som inte framställs i förvärvssyfte. Undantaget gäller fotografier med både kända och okända upphovsmän. Bilderna märks med ©. Det är upp till var och en att beakta eventuella upphovsrätter. SWEDISH NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD RIKSANTIKVARIEÄMBETET Cultural Monuments in S weden 7 Glimmingehus Anders Ödman National Heritage Board Back cover picture: Reconstruction of the Glimmingehus drawbridge with a narrow “night bridge” and a wide “day bridge”. The re construction is based on the timber details found when the drawbridge was discovered during the excavation of the moat. Drawing: Jan Antreski. Glimmingehus is No. 7 of a series entitled Svenska kulturminnen (“Cultural Monuments in Sweden”), a set of guides to some of the most interesting historic monuments in Sweden. A current list can be ordered from the National Heritage Board (Riksantikvarieämbetet) , Box 5405, SE- 114 84 Stockholm. Tel. 08-5191 8000. Author: Anders Ödman, curator of Lund University Historical Museum Translator: Alan Crozier Photographer: Rolf Salomonsson (colour), unless otherwise stated Drawings: Agneta Hildebrand, National Heritage Board, unless otherwise stated Editing and layout: Agneta Modig © Riksantikvarieämbetet 2000 1:1 ISBN 91-7209-183-5 Printer: Åbergs Tryckeri AB, Tomelilla 2000 View of the plain. Fortresses in Skåne In Skåne, or Scania as it is sometimes called circular ramparts which could hold large in English, there are roughly 150 sites with numbers of warriors, to protect the then a standing fortress or where legends and united Denmark against external enemies written sources say that there once was a and internal division. -

MINUTES of the PARISH COUNCIL MEETING HELD for BEETLEY & EAST BILNEY by ZOOM on THURSDAY 3Rd SEPTEMBER 2020 at 7.30 P.M

MINUTES OF THE PARISH COUNCIL MEETING HELD FOR BEETLEY & EAST BILNEY BY ZOOM ON THURSDAY 3rd SEPTEMBER 2020 AT 7.30 P.M. Present Councillor J. O’Donovan (Chair) Councillor S. Boyce (After Co-Option) Councillor J. Baldwin Councillor H. Johnson Councillor R. Richmond District Councillor R Atterwill District Councillor R Duffield Seven members of the public. 1. Apologies for Absence. Apologies for absence were received from County Councillor Mark Kiddle-Morris. 2. To receive Declaration of Pecuniary Interests. There were no DPI’s . 3. Minutes of the previous meeting Councillor Baldwin proposed and Councillor Richmond seconded the resolution that the minutes of the previous meeting held on16th. July 2020 having been circulated be approved. All were in favour and the minutes were duly signed by the Chairman of the meeting. 4. Co-option to the Parish Council Councillor Richmond proposed and Councillor Johnson seconded the resolution that Mr. Stephen Boyce be co-opted onto the Parish Council. All were in favour. The Chairman welcomed Councillor Boyce to the Parish Council and the declaration of acceptance of office was duly signed and witnessed. 5. Resignations from the Parish Council Letters of resignation had been received from Councillors Rose and Leigh and these were accepted. The Chairman thanked them for all of the work they had done for the Parish Council. 6. Public participation. 6.1 County and District Councillors reports County Councillor Kiddle-Morris had forwarded his report as below Covid-19: The latest information from NCC on the measures and response to the Covid-19 outbreak in Norfolk has been forwarded to you all. -

Partisan Dealignment and the Rise of the Minor Party at the 2015 General Election

MEDIA@LSE MSc Dissertation Series Compiled by Bart Cammaerts, Nick Anstead and Richard Stupart “The centre must hold” Partisan dealignment and the rise of the minor party at the 2015 general election Peter Carrol MSc in Politics and Communication Other dissertations of the series are available online here: http://www.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research/mediaWorkingPapers/Electroni cMScDissertationSeries.aspx MSc Dissertation of Peter Carrol Dissertation submitted to the Department of Media and Communications, London School of Economics and Political Science, August 2016, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the MSc in Politics and Communication. Supervised by Professor Nick Couldry. The author can be contacted at: [email protected] Published by Media@LSE, London School of Economics and Political Science ("LSE"), Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. The LSE is a School of the University of London. It is a Charity and is incorporated in England as a company limited by guarantee under the Companies Act (Reg number 70527). Copyright, Peter Carrol © 2017. The authors have asserted their moral rights. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. In the interests of providing a free flow of debate, views expressed in this dissertation are not necessarily those of the compilers or the LSE. 2 MSc Dissertation of Peter Carrol “The centre must hold” Partisan dealignment and the rise of the minor party at the 2015 general election Peter Carrol ABSTRACT For much of Britain’s post-war history, Labour or the Conservatives have formed a majority government, even when winning less than half of the popular vote. -

1 the TROUBLE with ARISTOCRACY Hans Van

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery 1 THE TROUBLE WITH ARISTOCRACY Hans van Wees and Nick Fisher ‘The history of aristocracies … is littered with self-serving myths which outsiders have been surprisingly willing to accept uncritically’, a recent study warns (Doyle 2010, xv). Our volume shows that ancient ‘aristocracies’ and their modern students are no exception. In antiquity, upper classes commonly claimed that they had inherited, or ought to have inherited, their status, privilege and power because their families excelled in personal virtues such as generosity, hospitality and military prowess while abstaining from ignoble ‘money-making’ pursuits such as commerce or manual labour. In modern scholarship, these claims are often translated into a belief that a hereditary ‘aristocratic’ class is identifiable at most times and places in the ancient world, whether or not it is in actually in power as an oligarchy, and that deep ideological divisions existed between ‘aristocratic values’ and the norms and ideals of lower or ‘middling’ classes. Such ancient claims and modern interpretations are pervasively questioned in this volume.1 We suggest that ‘aristocracy’ is only rarely a helpful concept for the analysis of political struggles and historical developments or of ideological divisions and contested discourses in literary and material cultures in the ancient world. Moreover, we argue that a serious study of these subjects requires close analysis of the nature of social inequality in any given time and place, rather than broad generalizations about aristocracies or indeed other elites and their putative ideologies. -

Aristocratic Identities in the Roman Senate from the Social War to the Flavian Dynasty

Aristocratic Identities in the Roman Senate From the Social War to the Flavian Dynasty By Jessica J. Stephens A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Greek and Roman History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Potter, chair Professor Bruce W. Frier Professor Richard Janko Professor Nicola Terrenato [Type text] [Type text] © Jessica J. Stephens 2016 Dedication To those of us who do not hesitate to take the long and winding road, who are stars in someone else’s sky, and who walk the hillside in the sweet summer sun. ii [Type text] [Type text] Acknowledgements I owe my deep gratitude to many people whose intellectual, emotional, and financial support made my journey possible. Without Dr. T., Eric, Jay, and Maryanne, my academic career would have never begun and I will forever be grateful for the opportunities they gave me. At Michigan, guidance in negotiating the administrative side of the PhD given by Kathleen and Michelle has been invaluable, and I have treasured the conversations I have had with them and Terre, Diana, and Molly about gardening and travelling. The network of gardeners at Project Grow has provided me with hundreds of hours of joy and a respite from the stress of the academy. I owe many thanks to my fellow graduate students, not only for attending the brown bags and Three Field Talks I gave that helped shape this project, but also for their astute feedback, wonderful camaraderie, and constant support over our many years together. Due particular recognition for reading chapters, lengthy discussions, office friendships, and hours of good company are the following: Michael McOsker, Karen Acton, Beth Platte, Trevor Kilgore, Patrick Parker, Anna Whittington, Gene Cassedy, Ryan Hughes, Ananda Burra, Tim Hart, Matt Naglak, Garrett Ryan, and Ellen Cole Lee. -

Notice of Poll

NOTICE OF POLL Breckland Election of a County Councillor for Attleborough Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a County Councillor for Attleborough will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of County Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors BREMNER (Address in Norwich) Labour Party Philip A Spiby (+) Doris Piper (++) James Sinclair Candidate OLIVER 6 The Ridgeway, The Conservative Party Andrew Howard (+) Vera J Dale (++) Rhodri Acton, W3 8LL Candidate SPELLER 12 Goldfinch Drive, Liberal Democrat Christine Speller (+) Beverley Bulmer (++) Ian Francis Attleborough, NR17 1GT 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Station Ranges of electoral register numbers of Situation of Polling Station Number persons entitled to vote thereat Attleborough Connaught Hall - Francis Room, Station Road, 1 ATB1-1 to ATB1-2165 Attleborough Attleborough Baptist Church, Leys Lane, Attleborough 2 ATB2-1 to ATB2-1977 Besthorpe Silver Farm, Silver Street, Besthorpe, Attleborough 3 ATQ1-1 to ATQ1-636 Attleborough Town Hall, Queens Square, Attleborough 4 ATQ2-1 to ATQ2-1461 Attleborough Sports Hall, Queens Square, Attleborough 5 ATQ3-20 to ATQ3-1901 Attleborough Sports Hall, Queens Square, Attleborough 6 ATQ3-1902 to ATQ3-3753 5. Where contested this poll is taken together with the election of Parish Councillors and the election of Election of a Police and Crime Commissioner. -

Roman History the LEGENDARY PERIOD of the KINGS (753

Roman History THE LEGENDARY PERIOD OF THE KINGS (753 - 510 B.C.) Rome was said to have been founded by Latin colonists from Alba Longa, a nearby city in ancient Latium. The legendary date of the founding was 753 B.C.; it was ascribed to Romulus and Remus, the twin sons of the daughter of the king of Alba Longa. Later legend carried the ancestry of the Romans back to the Trojans and their leader Aeneas, whose son Ascanius, or Iulus, was the founder and first king of Alba Longa. The tales concerning Romulus’s rule, notably the rape of the Sabine women and the war with the Sabines, point to an early infiltration of Sabine peoples or to a union of Latin and Sabine elements at the beginning. The three tribes that appear in the legend of Romulus as the parts of the new commonwealth suggest that Rome arose from the amalgamation of three stocks, thought to be Latin, Sabine, and Etruscan. The seven kings of the regal period begin with Romulus, from 753 to 715 B.C.; Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, from 534 to 510 B.C., the seventh and last king, whose tyrannical rule was overthrown when his son ravished Lucretia, the wife of a kinsman. Tarquinius was banished, and attempts by Etruscan or Latin cities to reinstate him on the throne at Rome were unavailing. Although the names, dates, and events of the regal period are considered as belonging to the realm of fiction and myth rather than to that of factual history, certain facts seem well attested: the existence of an early rule by kings; the growth of the city and its struggles with neighboring peoples; the conquest of Rome by Etruria and the establishment of a dynasty of Etruscan princes, symbolized by the rule of the Tarquins; the overthrow of this alien control; and the abolition of the kingship. -

Romans History W2

The Romans: History Worksheet 2A Name: _____________________________ Date: ____________________ Can you fill in this pyramid to show the social structure of ancient Rome? Choose one of Which of these these names for groups do you think each of the labels: The you would have liked most to have belonged to and why? • plebeians important • emperor man in the • senators empire. He has • slaves lots of power. He is called the • patricians _______________. • consuls These two people were chosen every year to run the empire. They were called ________________. This group of people were very important and helped to make the laws of Rome. They were called __________________. These people were the aristocracy of Rome. They were rich and came from noble families. They were called __________________. These people were the ordinary working people of ancient Rome. They were usually poor but they were able to vote. They were called __________________. These people were the poorest of ancient Rome. They had no rights and had to work constantly. They were called __________________. Copyright © PlanBee www.planbee.com The Romans: History Worksheet 2B Name: _____________________________ Date: ____________________ Can you describe the social position of each of these groups of people? Try to include Which of these details about: groups do you think you would have liked • what they did Emperor to have belonged to for their work and why? • whether or not they could vote • how much power they had Consuls Senators Patricians Plebeians Slaves Copyright © PlanBee www.planbee.com The Romans: History Worksheet 2C Name: _____________________________ Date: ____________________ Can you write a definition for each of these ancient Roman terms? Monarchy Republic Empire Emperor Senate Senator Consul Patrician Plebeian Slave Freedman Copyright © PlanBee www.planbee.com The Romans: History Information Sheet A How ancient Rome was organised Until 509 BC, Rome had been a monarchy. -

Slaves, Coloni, and Status Confusion in the Late Roman Empire

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive National Collegiate Honors Council Spring 2017 Slaves, Coloni, and Status Confusion in the Late Roman Empire Hannah Basta Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchcjournal Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Higher Education Commons, Higher Education Administration Commons, and the Liberal Studies Commons Basta, Hannah, "Slaves, Coloni, and Status Confusion in the Late Roman Empire" (2017). Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive. 558. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchcjournal/558 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Collegiate Honors Council at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journal OF THE National Collegiate Honors Council PORTZ-PRIZE-WINNING ESSAY, 2016 Slaves, Coloni, and Status Confusion in the Late Roman Empire Hannah Basta Georgia State University INTRODUCTION rom the dawn of the Roman Empire, slavery played a major and essen- tial role in Roman society . While slavery never completely disappeared fromF ancient Roman society, its position in the Roman economy shifted at the beginning of the period called Late Antiquity (14 CE–500 CE) . At this time, the slave system of the Roman world adjusted to a new category of labor . Overall, the numbers of slaves declined, an event that historian Ramsey MacMullen, drawing from legal debates and legislation of the period, attri- butes to the accumulation of debt and poverty among Roman citizens in the third century CE . -

Unit 13 the Roman Empire

UNIT 13 THE ROMAN EMPIRE Structure 13.1 Introduction 13.2 The Roman Expansion 13.2.1 The First Phase 13.2.2 The Second Phase 13.3 Political Structure and Society 13.3.1 Social Orders and the Senate 13.3.2 Officials of the Republic 13.3.3 Struggle Between Patricians and Plebeians 13.3.4 The Assembly 13.3.5 Conflict of the Orders 13.3.6 Social Differentiation in Plebeians 13.4 Conflicts and Expansion 13.4.1 Professional Army and War Lords 13.4.2 Wars for Expansion 13.4.3 Struggle of War Lords with the Senate 13.5 Slavery 13.6 Summary 13.7 Exercises 13.1 INTRODUCTION You have read in Unit 12 that Alexander the Great created a vast, but shortlived empire, which was partitioned soon after his death. Following the end of the Persian empire, and with the disruption of the unity of Alexander’s Macedonian empire, a new political entity rose to prominence in the Mediterranean region. This was the Roman empire which became the largest and most enduring empire in antiquity. The nucleus of the empire lay in Italy and subsequently it encompassed the entire Mediterranean world. Roman expansion into the Mediterranean began soon after the break-up of the Macedonian empire. By this time the city of Rome in Italy had succeeded in bringing almost the entire Italian peninsula under its control. Rome was among the many settlements of Latin-speaking people in Italy. Latin forms part of the broad Indo-European group of languages. In the period after c. -

Guide to Local History and Parish Studies Select Bibliography

Resource Guide to Local History and Parish Studies Select Bibliography Norwich Cathedral Library May 2016 Norwich and Norfolk Church Guides and Pamphlets—Runnett Room Norwich Church Guides • All Saints Westlegate • St Andrew • St Augustine • St Andrew’s Hall • St Clement and St George • St Etheldreda • St George Colegate • St George Tombland • St Giles on the Hill • The Great Hospital and St Helen Bishopgate • St Gregory Pottergate • Greyfriars • St John the Baptist Catholic Cathedral • St John the Baptist Timberhill • St John Maddermarket • St John de Sepulchre Finkelgate • St Julian • St Laurence • The Lazar House (Sprowston Rd) • St Mary Coslany • St Mary the Less • St Michael Coslany • St Michael at Plea • Mousehold Heath, Chapel of St William • The Octagon Unitarian Church • The Old Meeting House Congregational Church • St Peter Hungate • St Peter Mancroft 2 • St Peter Parmentergate • SS Simon and Jude • St Stephen • Surrey Chapel • Combined Norwich churches guides (10) Norfolk Church Guides • Acle, St Edmund • Alby, St Ethelbert • Aldborough, St Mary • Ashwellthorpe, All Saints • Attleborough, St Mary • Aylmerton, St John the Baptist • Aylsham, St Michael • Baconsthorpe, St Mary • Bale, All Saints • Barney, St Mary • Barningham Winter, St Mary • Barton Turf, St Michael and All Angels • Bawburgh, SS Mary and Walstan • Beeston, St Lawrence • Beetley, St Mary Magdalene • Belaugh, St Peter • St Benet’s Abbey • Binham Priory • Bittering Parva, SS Peter and Paul • Blakeney, St Nicholas • Blickling, St Andrew • Blofield, SS Andrew and -

Chivalry in Medieval Portugal

Chivalry in Medieval Portugal Miguel Aguiar1 Abstract This article seeks to understand the different stages in the spread and development of chivalric ideals as a feature that marked the identity of the main socio-political groups in medieval Portugal. For this purpose, a diachronic approach is adopted, while, at the same time, a comparison is made with other European areas, especially the Iberian Christian kingdoms. The sources used for the writing of this study ranged from chronicles to genealogical literature, legislative compilations, chivalric treatises and diplomatic documents. Keywords Knight; knighthood; chivalry; aristocracy; nobility Resumo Este artigo tem como objetivo compreender as etapas de difusão e construção do ideal cavaleiresco enquanto marca identitária dos principais grupos sociopolíticos no Portugal Medieval. Para isso segue-se uma perspetiva diacrónica, mantendo igualmente uma visão comparativa com outros espaços políticos, nomeadamente os reinos cristãos peninsulares. Articular-se-á um conjunto diferenciado de fontes, englobando textos legislativos, tratadísticos, genealógicos e cronísticos. Palavras-chave Cavaleiro; cavaleiros; cavalaria; aristocracia; nobreza 1 University of Porto, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected] Aguiar Chivalry in Medieval Portugal In a letter addressed to his brother, King Duarte (r. 1433-1438), at the beginning of the 1430s, Prince João stated that the grandees of the kingdom could not be considered to be good men if they had not attained the honor of chivalry, which could be gained by performing an unquestionable feat of arms, under dangerous and even rash conditions (Livro dos Conselhos de el-rei D. Duarte: p. 47). The prince’s way of thinking provides clear evidence of how, in the fifteenth century, the chivalric spirit was considered a fundamental benchmark, not only for the monarchy and the nobility, but also for some of the urban elites that wished to rise up within the social hierarchy by undertaking armed deeds and thus adopting a lifestyle that was associated with the aristocracy.