The Attitudes of the Presidents of Lutheran Colleges and Universities Regarding the Nature and Limits of Free Expression for Students on Their Campuses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download 1 File

Maari Gould stays busy on campus Page 8 First ever Turkey Shoot Regals Forensic s volleyball team begins finishes #2 with a bang in nation Mangano receives Team ends with third best speaker only three losses The debate team opened its season last weekend with unexpected success at die By ANDRU MURAWA Pacific Coast Forensic Association's Fall Sports Editor Championships, advancing to die Sweet Sixteen elimination round. CLU's women's volleyball team put In that round, Rona Morich and Robert up a strong fight but fell just short in its Mangano lost a close decision to Southern California College. quest for the NCAA Division III champi- Mangano was ranked onship, losing to five time defending the third best speaker in a division that champion Washington University of Mis- included teams from UCLA and Pepperduic University. souri 15-6. 17-19. 13-15, 15-1 1. 15-1 1 in Whitewater, Wisconsin. Mangano'sfeat waseven more impressive The team finished the season with a because he was third out of 64 competitors record of 27-3, the best ever by a Regal and he has never competed at a debate volleyball team. tournament before. "I have mixed emotions," said sopho- Mark Jones, forensics coach, was nothing more setter Liz Martinez. "I was excited but smiles. "I thought were to finish second, but I was also disap- we going down to merely pointed that we were so close and didn't gain some experience; I had no idea we win." would do as as well as we did," he said. -

CLU Mag 11.1

THE MAGAZINE OF CALIFORNIA LUTHERAN UNIVERSITY CLUFALL 2003 VOLUME 11 NUMBER 1 MAGAZINE Centers in the Labyrinth of Time Celebrate the 40th anniversary of CLU’s first graduating class Participate in a special tribute during the 2004 Commencement ceremonies Saturday morning, May 15, and at different activities during the day For further information, please call the Alumni Office at (805) 493-3170 Celebrate the 40th anniversary of Fall 2003 VolumeVolume 11 NumberNumber 1 Managing Editor Carol Keochekian ’81 THE MAGAZINE OF CALIFORNIA LUTHERAN UNIVERSITY Editor CLU MAGAZINE Lynda Paige Fulford, MPA ’97 CLU’s first graduating class President’s Page . 4 Copy Editor Peggy L. Johnson Campus Highlights . 5 Alumni Editors Elaine Benditson, MBA ’03 Faculty Viewpoint . 12 Jennifer (Dowling ’94) Marsteen Sports Editor Crossword Puzzle . 26 Scott Flanders Calendar . 27 Art Director Michael L. Adams ’72 Alumni Assistant Mary Beth Plemons FEATURE STORIES Editorial Board ENTERS IN THE Members 11 C Mary (Malde ’67) Brannock LABYRINTH OF TIME Tim Hengst ’72 Bruce Stevenson ’80, Ph.D. CLU’s College of Arts and Sheryl Wiley Solomon Sciences is launching three new centers for learning that weave Mission of together professional training California Lutheran University California Lutheran University is a diverse schol- and the liberal arts. arly community dedicated to excellence in the liberal arts and professional studies. Rooted in the Lutheran tradition of Christian faith, the University 13 SUNDAY AFTERNOON encourages critical inquiry into matters of both faith and reason. The mission of the University WITH DESTA is to educate leaders for a global society who are strong in character and judgment, confident An alumna living abroad sets in their identity and vocation, and committed to 11 out to find the proverbial needle service and justice. -

Download 1 File

. California Lutheran University The Echo Volume 43, No. l 60 West Olsen Road, Thousand Oaks, CA 91360 September 11, 2002 Sports Features Calendar Athletic teams are back in Special September 11 section; Check out what 's going action with the start of the Reflections a year after on at CLU 2002-2003 school year the terrorist attack on America this week See stories pages 7 & 8 See story page 3 See story page 2 CLU students return to campus By Yvette Ortiz and Brett Rowland in the numerous events Student Life had open for students to change their sched- camera into their own hands projecting MANAGING EDITOR/CIRCULATION prepared for Orientation Weekend. ules, eat lunch at the "All Class Social," each other onto the screen. The DJs MANAGER AND ARTS/FEATURES EDITOR Painting the CLU rocks, preparing skits look for on-and-off-campus employ- played a steady stream of hip-hop music, for Froshfest and getting acquainted with ment, buy books and attend student loan supplemented with the occasional tech- for California Although classes the campus were a few of the activities. counseling or a CLUnet session. no-dance song. Lutheran University students did not "The rocks, those were the funnest," The "Back to School Dance," held The Sand Blast, the off-campus begin until Sept. 4, the campus has CLU said freshman David Zachs of Oxnard, by the Programs Board, kicked off the beach trip held every year, was the last students since 3 1 been occupied by Aug. Calif. Despite a few injuries caused by first Club Lu event of the year last Friday event to welcome students during the In the extreme heat of Orientation the surrounding barbed wire, students night as part of the students' first week- first week. -

In Urban Ed Radical Thinkers Wanted Help Spread the Word About Rossier’S Innovative Graduate Programs

USC Rossier School of Education Magazine : Winter/Spring 2011 in Urban Ed Radical Thinkers Wanted Help spread the word about Rossier’s innovative graduate programs Master’s Degrees • Marriage and Family Therapy • School Counseling • Higher Education Counseling • Postsecondary Administration and Student Affairs - emphases in Student Affairs and Athletic Administration • Teaching - offered both on campus and online • Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages - offered both on campus and online Doctoral Degrees • Doctor of Education (Ed.D.) - Three- year program for scholar-practitioners • Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Education Policy (Ph.D.) - Fully-funded four-year program preparing faculty and educational researchers Rossier students Syndia Limon, Brian Boyle, Ying-Yun Chang http://rossier.usc.edu If you know someone with the potential to At the University of Southern California’s Rossier School be an educational leader, email that of Education, we continue to build upon our exceptional reputation as a leader in urban education with these core person’s name and contact information to commitments: [email protected]. > Guaranteeing a diverse school community > Offering a personalized student experience > Seeking innovative approaches to learning A Rossier staff member will follow up with > Providing opportunities for global exchange information about our programs. > Uniting theory and practice Futures-Jan-2011-a.indd 1 1/27/2011 3:44:52 PM Winter / Spring 2011 Radical Thinkers in Urban Ed Wanted Help spread the word about Rossier’s innovative graduate Rossier gathers the best and brightest to undertake programs what President Nikias calls USC’s “Great Journey” 6 Master’s Degrees • Marriage and Family Therapy • School Counseling FEATURES • Higher Education Counseling Radical Believers • Postsecondary Administration and Profiles of dedicated Rossier fans who Student Affairs - emphases in Student put their time and money where their belief is Affairs and Athletic Administration Ira W. -

CLU Mag 11.3.Indd

THE MAGAZINE OF CALIFORNIA LUTHERAN UNIVERSITY CLU MAGAZINESUMMER 2004 VOLUME 11 NUMBER 3 BREAKING FINDINGTHE TREATMENTSCODE: FOR THE WORLD’S MOST DEVASTATING VIRUSES Publisher Ritch K. Eich, Ph.D. Summer 2004 Volume 11 Number 3 Mark your place in CLU’s history Editor in Chief Carol Keochekian ’81 Here is a unique opportunity to gain recognition in Cal Lutheran’s new Sports and Fitness Copy Editor Peggy L. Johnson Center with a brick or tile that bears your name or that of a loved one. THE MAGAZINE OF CALIFORNIA LUTHERAN UNIVERSITY Art Director Michael L. Adams ’72 Editor’s Page . .4 Sports Editor Scott Flanders President’s Page . .5 Alumni Editor Campus Highlights . .6 Elaine Benditson, MBA ’03 Sports Highlights . 10 Class Notes Assistant Editor Doris Daugherty Calendar . 31 Contributing Writers Lynda Paige Fulford, MPA ’97 FEATURE STORIES Della Greenlee ’82 Editorial Board Members 12 Looking Back Bryan Card ’01 Retiring professor Dr. J. T. Ledbetter Randall Donohue, Ph.D. takes a warm look back at 34 years Lynda Paige Fulford, MPA ’97 Mike Fuller, MS ’97 of joy and promise as a CLU faculty Tim Hengst ’72 member. Jennifer (Dowling ’94) Marsteen Michael McCambridge, Ed.D. Ryann (Hartung ’99) Moresi Sheryl Wiley Solomon Bruce Stevenson ’80, Ph.D. Cynthia Wyels, Ph.D. 12 15 On the Air! 10 Years and Mission of Counting... California Lutheran University From sign-on celebration to 10th anni- California Lutheran University is a diverse scholarly community dedicated to excellence in versary, it’s been a wild, rewarding ride the liberal arts and professional studies. -

CLU Mag 10.2

BODY•MIND•SOUL CLU MAGAZINE NOW IS THE Share in the dream. Naming opportunities starting at $250. See the enclosed envelope, visit www.clunet.edu/campaign, or e-mail us at [email protected] NOW IS THE TIME THE CAMPAIGN FOR CLU TIME NON PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID VAN NUYS CALIFORNIA SPECIAL PERMIT NO. 987 CAMPAIGN ISSUE THE MAGAZINE OF CALIFORNIA LUTHERAN UNIVERSITY BODY•MIND•SOUL CLUSPRING 2003 VOLUME 10 NUMBER 2 MAGAZINE NOW IS THE TIME SPECIAL CAMPAIGN ISSUE The joy of sharing “We chose to create an endowed scholarship at Cal Lutheran because we felt it would be an important way to make a last- ing contribution to the University. We understand that the University’s endowment is vital to its long-term success and its ability to help students meet their many financial needs. We also like knowing that we can continue adding to the fund over many years, and that it will help students year after year. We could think of no better way to support our alma mater.” Roger ’89, Debra (Anderson ’91, TC ’92)and Zack Niebolt Coral Springs, Fla. CLU ANNUAL FUND GIVING THAT MAKES A DIFFERENCE California Lutheran University Office of Development (805)493-3829 Spring 2003 VolumeVolume 10 NumberNumber 2 Managing Editor Carol Keochekian ’81 THE MAGAZINE OF CALIFORNIA LUTHERAN UNIVERSITY Editor CLU MAGAZINE Lynda Paige Fulford, MPA ’97 Letters to the Editor . 4 Copy Editor Peggy Johnson President’s Page . 5 Alumni Editors Elaine Benditson Faculty Viewpoint . 6 Jennifer (Dowling ’94) Marsteen Campus Highlights . 7 Sports Editor Scott Flanders Sports Scoreboard . -

2015-2016 Annual Report

Westridge School / envisioning the Future 2015-2016 Annual Report 324 Madeline Drive envisioning Pasadena, CA 91105 the Future Impact Starts Here, With You. Westridge School / envisioning the Future 2015-2016 Annual Report FROM THE head & board chair Dear Members of the Westridge Community, been raised toward the ultimate $15 million campaign When educators are asked why they do what they do, they often comment goal to fortify the school’s on how they are inspired by their students and that through them, they endowment. Gifts to the touch the future. Though you may not teach, when you support Westridge, endowment are investments you too affect the future in ways more expansive and enduring than you in the future of Westridge. may have considered. The fund is invested, growing each year to ensure the From a very literal perspective, giving to the Annual Fund—The Westridge financial viability of Westridge Difference—provides critical funds for each school year; but its true and its vision for the next impact rests not only in the here and now, but in the future. The programs century of leadership and and opportunities you support now enable our students to grow and thrive, excellence in girls’ education. to set their sights high, and to be among the next generation of leaders. Details of the Campaign, which entered its public phase in October of this Students such as Alexandria Myers ’14, a legislative intern on Capitol Hill year, can be found on page 4 of this report. who plans a career fighting for women and girls’ education internationally. -

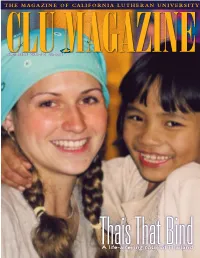

CLU Mag 10.3

THE MAGAZINE OF CALIFORNIA LUTHERAN UNIVERSITY CLUSUMMER 2003 VOLUME 10 NUMBER 3MAGAZINE ThaisA life-altering That tour of Bind Thailand The joy of sharing “We support California Lutheran University for several reasons. First, over the years, CLU graduates have fulfilled the mission and purpose of the University by becoming successful leaders and entrepreneurs in their chosen careers. Second, the faculty, administrative staff and students contribute so much to Thousand Oaks and the surrounding communities through their service and leadership. It is a privilege for us to be partners with CLU and its alumni, faculty, staff and students.” Barbara and Norman Lueck Thousand Oaks, Calif. CLU ANNUAL FUND GIVING THAT MAKES A DIFFERENCE California Lutheran University Office of Development (805)493-3829 Summer 2003 VolumeVolume 10 NumberNumber 3 Managing Editor Carol Keochekian ’81 THE MAGAZINE OF CALIFORNIA LUTHERAN UNIVERSITY Editor CLU MAGAZINE Lynda Paige Fulford, MPA ’97 Copy Editor President’s Page . 4 Peggy Johnson Campus Highlights . 5 Alumni Editors Elaine Benditson, MBA ’03 Sports Scoreboard . 8 Jennifer (Dowling ’94) Marsteen Sports Editor Crossword Puzzle . 28 Scott Flanders Faculty Viewpoint . 30 Art Director Michael L. Adams ’72 Calendar . 31 Editorial Board Members Mary (Malde ’67) Brannock Tim Hengst ’72 FEATURES Bruce Stevenson ’80, Ph.D. Sheryl Wiley Solomon 11 THE THAIS THAT BIND Sociology professor Dr. Charles Mission of 1616 California Lutheran University Hall takes students on a life- California Lutheran University is a diverse schol- altering tour of Thailand – from arly community dedicated to excellence in the liberal arts and professional studies. Rooted in the the misery of Bangkok to the joy Lutheran tradition of Christian faith, the University of a remote orphanage in the encourages critical inquiry into matters of both faith and reason.